Australia's mental health system

On this page:

Overview

Mental health is a key component of overall health and wellbeing (WHO 2021). In any year in Australia, an estimated 1 in 5 people aged 16–85 will experience a mental disorder (ABS 2022). A person’s mental health affects and is affected by multiple factors, including lower (by SES status) access to services (health and/or other services), living conditions and employment status, and affects not only the individual but also their families and carers (Slade et al. 2009; WHO 2021). Mental health and physical health are related and people with mental illnesses are more likely to develop physical illness and tend to die earlier than the general population (Lawrence et al. 2013).

Throughout this web report, the terms ‘mental illness’ and ‘mental disorder’ are both used to describe a wide range of mental health and behavioural disorders, which can vary in both severity and duration.

A range of mental health‑related services are funded in Australia by various levels of government and/or individuals with services delivered by both government and non-government providers. For example, the Australian Government funds consultations with specialist medical practitioners, general practitioners (GPs), psychologists and other allied health practitioners through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), other primary mental health services through the Primary Health Networks, and support for psychosocial disabilities through the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Access to psychiatrists, psychologists and other allied health professionals may, dependent on eligibility, be subsidised through initiatives such as Better Access initiative. State and territory governments provide mental health services including through public hospitals, including emergency departments, residential mental health care and community mental health care services.

In addition to specialised services, government and non-government providers provide support to population mental health crisis and support services, such as Lifeline and Beyond Blue. Mental health care is also provided in private hospitals.

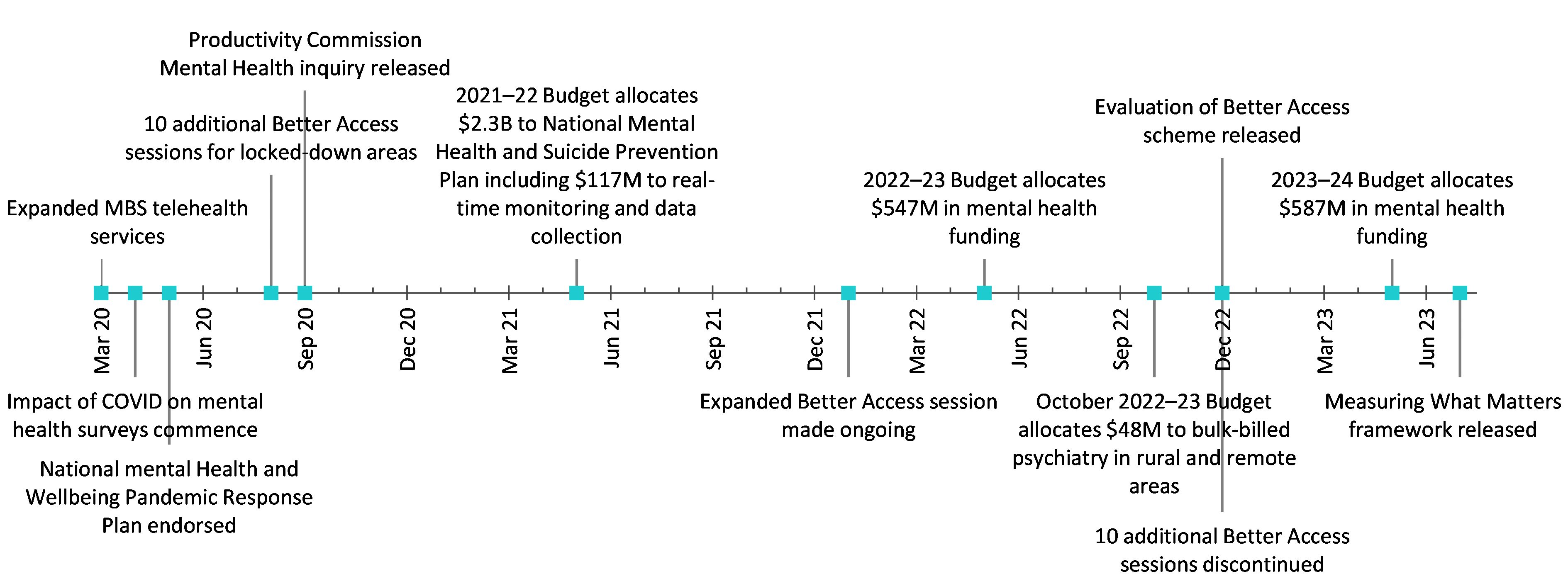

Recent national developments

In November 2020, the Productivity Commission released the final report of the Mental Health Inquiry, a guide to reforming Australia’s mental health system to create a person-centred mental health system (Productivity Commission 2020). The Productivity Commission found that Australia’s current mental health system is not comprehensive, and that reform of the mental health system would produce large benefits in quality of life for people with mental ill-health valued at up to $18 billion annually, with an additional annual benefit of $1.3 billion due to increased economic participation. The review placed an emphasis on prevention and early intervention, and on the importance of mental health consumer and carer involvement in all aspects of the mental health system.

In the 2021–22 Federal Budget, $2.3 billion over 4 years was allocated to the National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan, responding to recommendations from the Productivity Commission’s Inquiry Report on Mental Health, the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System and advice from the National Suicide Prevention Advisor (Department of the Treasury 2021). The majority of these recommendations require collaboration between the Australian Government and state and territory governments, including through the National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement. The plan included 5 pillars to this investment which address:

- Prevention and early intervention

- Suicide prevention

- Treatment

- Supporting the vulnerable

- Workforce and governance.

A further $547 million was allocated to support these pillars in the 2022–23 Budget (DoH 2022b). Additionally, the 2023–24 Budget allocated $586.9 million to action and expand projects. These include:

- Projects to provide psychosocial support services for those with severe mental illness not covered by the NDIS.

- Opening and/or announcing more than 20 Head to Health and headspace centres since the previous budget, including services in remote, regional, and underserved communities and allocating resources to increase interpreting services across these services.

- Rolling out programs targeting students, farmers, parents, and refugees which focus on wellbeing and suicide prevention (refer to National mental health policies and strategies below).

- From January 2022, expanded telehealth services were made an ongoing feature of MBS arrangements (DoH, 2022). As part of the October 2022–23 Federal Budget, $47.7 million was also allocated to restore MBS-subsidised bulk billing psychiatry services in rural and regional Australia that were previously removed in December 2021.

The National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreements, struck with each state and territory, further detail roles, responsibilities and co-funding arrangements (Department of the Treasury 2022)

In the 2021–22 Budget,

- $117 million was provided to establish a comprehensive evidence base to support real time monitoring and data collection for our mental health and suicide prevention systems, enabling services to be delivered to those who need them, and improving mental health outcomes for Australians (Department of the Treasury 2021).

- In December 2022, the Australian Government released the independent Evaluation of the Better Access Initiative. Better Access provides Medicare rebates to those with diagnosed mental disorders to facilitate access to mental health services. It was found those who received treatment through Better Access tended to have positive outcomes. However, some groups were found to be better served than others with those in lower socioeconomic, regional, rural, and remote and aged care residents seeing fewer benefits (Pirkis et al. 2022).

- The 10 additional psychological therapy sessions, initially provided during the COVID-19 pandemic, were discontinued as of 31 December 2022. The Government will focus on improving Better Access to be more equitable incorporating lived experience and mental illness experts.

- In July 2023, Treasury released the Measuring What Matters Framework, intended to measure and track various wellbeing themes, many of which, including psychological distress, are covered in the AIHW's Australia's welfare publication.

During the acute stages of the pandemic, all Australian Governments progressively introduced measures to mitigate mental health impacts as the situation developed. While a more comprehensive overview of the mental health impacts of the pandemic can be found in the archived content, some key events from the Australia Government response included:

- March 2020 – Expanding Medicare-subsidised telehealth services, including new MBS items for providers to provide telehealth services (DoH 2020). Additional funding to crisis lines, digital and online services, and support for healthcare professionals including funding of a dedicated Coronavirus Mental Wellbeing Support Service for free 24/7 mental health support.

- April 2020 – Conducting surveys into the adverse impacts of the pandemic on the mental health of Australians by the Australian National University, University of Melbourne and headspace.

- May 2020 – Endorsement of the National mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan by the National cabinet (NMHC 2020) with an additional $48.1 million committed to support priority areas.

- August 2020 – Expanding MBS-subsidised services under the Better Access initiative to provide 10 additional individual psychological therapy sections for those in areas subjected to lockdown restrictions, which were subsequently granted to all Australians as part of the October Budget. More information on the Australian Government Response to COVID-19 can be found on the Better Access page.

Additionally, each state and territory government also introduced a range of mental health support packages to benefit their residents. More information on jurisdictional responses can be found on the websites of each state and territory health department.

National mental health policies and strategies

The Australian Government and all state and territory governments share responsibility for mental health policy and the provision of support services for Australians living with a mental disorder. State and territory governments are responsible for the funding and provision of state and territory public specialised mental health services and associated psychosocial support services. The Australian Government funds primary care and out of hospital specialised care through the Medicare Benefits Schedule and also funds a range of services for people living with mental health difficulties. These provisions are coordinated and monitored through a range of initiatives, including nationally agreed strategies and plans.

The importance of good mental health, and its impact on Australians, has long been recognised by Australian governments. Over the last 3 decades governments have worked together to develop mental health programs and services to better address the mental health needs of Australians. The National Mental Health Strategy included five 5-year National Mental Health Plans which cover the period 1993 to 2022 (DoH 2018), with the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) National Action Plan on Mental Health overlapping between 2006 and 2011.

In March 2022, the National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement (National Agreement) came into effect, signed by the Australian Government and all states and territory governments. The National Agreement seeks to deliver a comprehensive, coordinated, consumer-focused mental health and suicide prevention system with joint accountability across all governments. Key priority areas under the National Agreement include regional planning and commissioning, priority populations, stigma reduction, safety and quality, gaps in the system of care, suicide prevention and response, psychosocial supports outside the NDIS, national consistency for initial assessment and referral, workforce, and data and evaluation.

The National Agreement is supported by bilateral schedules with all state and territory governments, which commit to joint investment from the Commonwealth and states and territory governments in mental health and suicide prevention services. The bilateral schedules focus on providing community-based services to address gaps in the mental health and suicide prevention system, and include varying commitments such as adult, youth and child mental health services, perinatal measures and suicide prevention services.

Monitoring mental health consumer and carer experiences is a long-term goal of the National Mental Health Strategy. More information on consumer and carer experiences is progressively becoming available through the implementation of the Your Experience of Service (YES) survey, which is currently used in some jurisdictions in Australia. It is offered to consumers who interact with specialised state and territory mental health services and aims to help these services and mental health consumers to work together to build better services. More information on the YES survey can be found in the Consumer perspective of mental health care section. Information on the outcomes of mental health care is also reported to gauge the effectiveness of mental health services from the perspective of both clinicians and consumers. These data form part of the National Outcomes and Casemix Collection (NOCC) More information can be found in the Consumer outcomes of mental health care section.

Most recently, the Australian Government has served to address gaps in the current mental health system by proposing and/or funding updated policy. These include:

- Funding of Medicare bulk billing services for allied health professionals including psychologists for mental health services via the MBS in rural and remote areas facilitated by a new Memorandum of Understanding with all states and the NT.

- Beginning rollout of 60-day dispensation of prescription medicines (following 2018 recommendations) subsidised through the PBS and further supporting electronic prescription infrastructure.

- Shifting of approach to suicide prevention from strictly mental health to a whole-of-life approach, including establishing the National Suicide Prevention Office Advisory Board comprised of experts, across academia, research, government, and peak bodies, and supported by the establishment of the National Suicide Prevention Office Lived Experience Partnership Group.

- Elevating lived experience voices through funding for the establishment and operation of two independent national mental health lived experience peak bodies with one to represent consumers, and one to represent carers, family and kin.

- Development of a new National Disaster Mental Health and Wellbeing Framework to provide guidance on mental health response following national disasters.

- Commissioning an independent review into Health Practitioner Regulatory settings related to approval of overseas applications of health workforce to address workforce shortages.

- Funding identified priority research areas such as loneliness and eating disorders.

Roles and responsibilities

There is a division of roles and responsibilities in Australia’s mental health system, with services being delivered and/or funded by the Australian Government, state and territory governments and the private and non-government sectors.

The Australian Government funds a range of mental health-related services through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS)/Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS) and Primary Health Networks. The Australian Government also funds a range of programs and services which provide essential support for people with mental illness. These include income support, social and community support, disability services, workforce participation programs, and housing.

State and territory governments fund and deliver public sector mental health services that provide specialist care for people experiencing mental illness. These include specialised mental health care delivered in public acute and psychiatric hospital settings, state and territory specialised community mental health care services, and state and territory specialised residential mental health care services. In addition, states and territories provide non-specialised hospital services used by people with mental illness (such as emergency departments and non-specialised admitted units) and other mental health-specific services in community settings such as supported accommodation and social housing programs.

There are a range of crisis, support and information services such as Beyond Blue, Lifeline, Kids Helpline, ReachOut and Head to Health.

Private sector services include admitted patient care in a private psychiatric hospital and private services provided by psychiatrists, psychologists and other allied health professionals. Private health insurers fund treatment costs in private hospitals, public hospitals and out of hospital services provided by health professionals.

Non-government organisations are private organisations (both not-for-profit and for-profit) that receive government and/or private funding. Generally, these services focus on providing wellbeing programs, support and assistance to people who live with a mental illness rather than the assessment, diagnostic and treatment tasks undertaken by clinically-focused services.

Service access

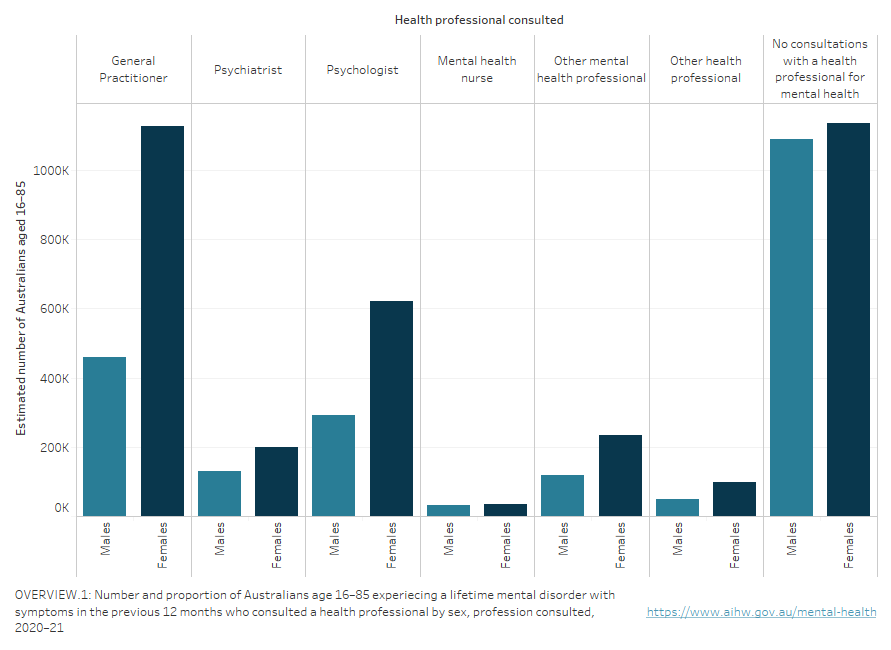

The 2020–21 National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing collected data on mental health service access in the preceding 12 months. From this survey, it is estimated that 3.4 million Australians aged 16–85 saw a health professional for their mental health in the previous 12 months (ABS 2022). Of those with a lifetime mental disorder who experienced symptoms within the last 12 months:

- 38% consulted a general practitioner, although it cannot be determined from this data whether this was specifically related to their mental health.

- 22% consulted a psychologist

- 8% consulted a psychiatrist.

Which health professions did Australians consult for mental health?

This figure shows the number of males and females who accessed mental health professionals in the previous 12 months. Health professionals include GP's, Psychiatrists, Psychologists, mental health nurses other mental health professionals and no consultation with a health professional for mental health.

Note: Some estimates have a relative standard error greater than 25% and should be interpreted with caution. Refer to National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing methodology, 2020-21, Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) for more information.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary Results, 2020–21; Tables 6.1, 6.3.

An estimated 860,000 Australians aged 16–85 also accessed at least one digital service used for mental health, such as crisis support, treatment programs or information from late 2020 to mid 2021 (ABS 2022).

Of those who did not access mental health care, the majority (89%) reported that they perceived having no need for any mental health care.

In 2020–21, 49% of MBS mental health specific services were provided by psychologists (including clinical psychologists), 27% were provided by general practitioners (GPs) and 19% were provided by psychiatrists (AIHW 2023).

ABS (2022) National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing, ABS, accessed 26 July 2022.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021) Mental Health Services in Australia - Medicare-subsidised mental health specific services, accessed 22 September 2023.

DoH (Australian Government Department of Health) (2018) The Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan, DoH, Canberra.

DoH (2020) Medicare Benefits Schedule Book, effective March 2020, DoH, Canberra, accessed 1 August 2022.

DoH (2022a) MBS Telehealth Services from January 2022, DoH, Canberra, accessed 1 August 2022.

DoH (2022b) Budget 2022–23: Prioritising mental health, preventive health and sport, DoH, Canberra, accessed 1 August 2022.

Department of the Treasury (2021) Budget 2021-22, Department of the Treasury, Canberra, accessed 1 August 2022.

Department of the Treasury (2022) The National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement, Department of the Treasury, Canberra, accessed 6 September 2023.

Lawrence D, Hancock K and Kisely S (2013) ‘The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: retrospective analysis of population based registers’, British Medical Journal, 346, doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f2539, accessed 1 August 2022.

NMHC (National Mental Health Commission) (2020) National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan, NMHC, Canberra, accessed 1 August 2022.

Pirkis J, Currier D, Harris M and Mihalopoulos C (2022) Evaluation of Better Access, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, accessed 8 August 2023.

Productivity Commission (2020) Mental Health: Productivity Inquiry Report Volume 1, No. 95, 30 June 2020, Productivity Commission, Canberra, accessed 1 August 2022.

Slade T, Johnston A, Teesson M, Whiteford H, Burgess P, Pirkis J and Saw S (2009) The Mental Health of Australians 2. Report on the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra, accessed 1 August 2022.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2021) Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2030, WHO, Geneva, accessed 1 August 2022.

This section was last updated in October 2023.