Mental health workforce

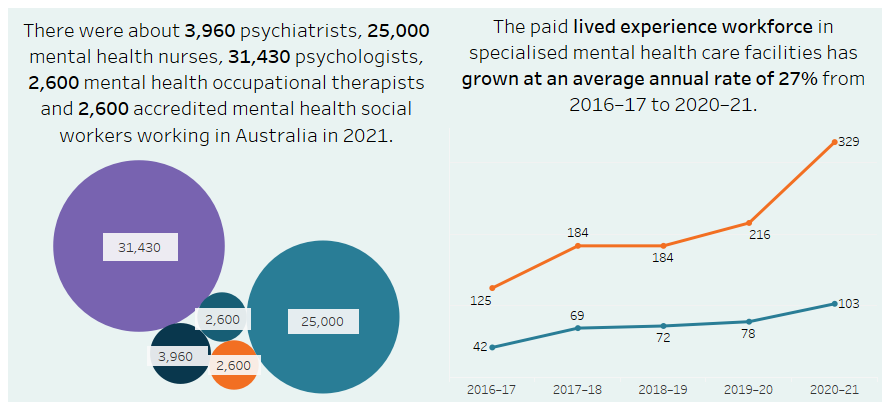

Two visualisations showing two key points in this section.

There were about 3,960 psychiatrists, 25,000 mental health nurses, 31,430 psychologists, 2,600 mental health occupational therapists and 2,600 accredited mental health social workers working in Australia in 2021.

The paid lived experience workforce in specialised mental health care facilities has grown at an average annual rate of 27% from 2016–17 to 2020–21.

Although there is no universal definition of what a ‘mental health worker’ is, there is broad agreement that the workforce is divided into three inter-related sectors - specialist, generalist and lived experience (Cleary, Thomas and Boyle 2020). This section is broadly structured into specialist, generalist and lived experience sections, although it should be noted that these categories are by no means definitive or mutually exclusive.

Specialist workers

Specialist workers provide mental health services directly and may include professionals with tertiary training in a mental health-related field. For the purpose of this section, the specialist workforce is considered to include psychiatrists, mental health nurses, psychologists, mental health occupational therapists and accredited mental health social workers.

Generalist workers

Generalist workers include other professionals who engage in mental health-related work or with people experiencing mental illness, but who may not have specialist training in mental health. Alternatively, generalist workers may include people in administrative or research roles that support the specialist workforce.

Lived experience workers

Lived experience workers, also called peer workers, are people who have themselves experienced mental illness or cared for someone who has, and can bring valuable insight into the caring experience. People with lived experience may also have specialist or generalist qualifications.

Spotlight data: How many specialist mental health workers are employed in Australia?

Maps of Australia showing the number and rate per 100,000 population of psychiatrists, mental health nurses, psychologists, mental health occupational therapists and accredited mental health social workers by state or territory, remoteness area, Primary Health Network (PHN) or Statistical Area 4 (SA4).

Notes:

- The number for each variable may not sum to the total due to the estimation process, rounding, not stated/missing data and/or confidentialisation.

- Regions without data will display as ‘0’. Refer to data tables for more detail.

- Crude rate is based on the Australian estimated resident population as at 30 June 2021.

Source: Mental health workforce 2021 tables, WK.2, WK.5, WK.8, WK.11, WK.14

Mental health workers may be employed in a wide variety of settings, including state-run health services, private or not-for-profit care providers, and/or private practice. Each state and territory has a mental health workforce plan (Cleary, Thomas and Boyle 2020), intended to guide and support the development of the mental health workforce to ensure it meets the needs of residents. A 10-year national mental health workforce strategy was released in late 2023. For further information, refer to the National Mental Health Workforce Strategy 2022-2032.

Specialist workers

This section provides data on the number of psychiatrists, mental health nurses, psychologists, mental health occupational therapists and accredited mental health social workers who are employed in Australia.

The first 4 of these professions are regulated by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). Mental health social workers are accredited by the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) as having specialist mental health expertise.

In 2021, there were about 3,960 psychiatrists, 25,000 mental health nurses, 31,430 psychologists, 2,600 mental health occupational therapists and 2,600 accredited mental health social workers working in Australia.

The majority of psychiatrists in 2021 were male (58%), although the number of female psychiatrists has increased at more than twice the average annual rate of males from 2017 to 2021 (5% and 2%, respectively). The other 3 professions were overwhelmingly female, comprising 71% of mental health nurses, 80% of psychologists, 85% of the mental health occupational therapists and 84% of accredited mental health social workers (Figure WK.1).

In 2023, of accredited mental health social workers surveyed, an average of 24 clinical hours per week and 8 hours in non-clinical work were reported. Over 90% of those surveyed reported that they had practiced via telehealth in the previous 12 months.

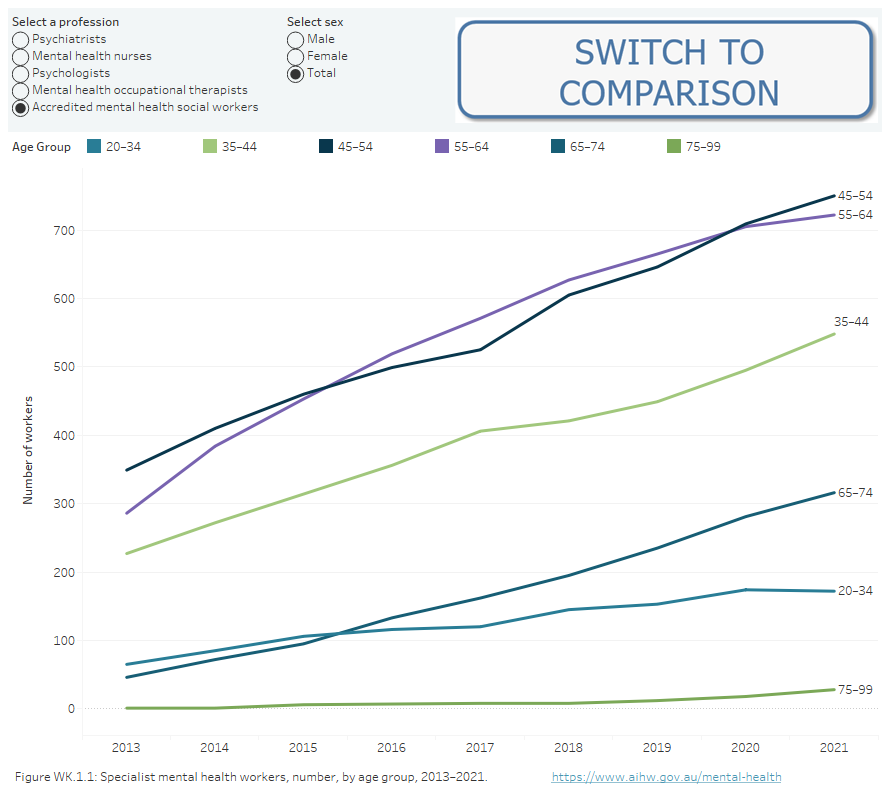

Figure WK.1: Specialist mental health workers, number, by age group, sex, 2013–2021

WK.1.1 is a line chart showing the number of people working in each profession by sex and age group from 2013 to 2021. In 2021, the most numerous age group for psychiatrists was 45–54, mental health nurses 20–34, psychologists 35–44, mental health occupational therapists 20–34, accredited mental health social workers 45–54.

WK.1.2 is a horizontal butterfly bar chart showing the number of each profession in each age group by sex and year. In 2021, the largest group of psychiatrists are males aged 45–54 (698), mental health nurses females aged 20–34 (4,882), psychologists females aged 35–44 (7,495), mental health occupational therapists females aged 20–34 (981), accredited mental health social workers females aged 45–54 (638).

Note: The number for each variable may not sum to the total due to the estimation process, rounding, not stated/missing data and/or confidentialisation.

Source: Mental health workforce 2021 tables, WK.1, WK.4, WK.7, WK.10, WK.13

In 2021, there were 187 fewer psychologists working in Australia than in 2020. Although this only represents a decrease of 0.6% relative to 2020 numbers, it is the first time since the national registration scheme began publishing data in 2013 that numbers have reduced year on year for any of the professions reported here (Figure WK.1). The decrease is seen for older age groups (55 years and over) and comes after a larger than trend increase in numbers from 2019 to 2020.

Measures introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic provide a possible explanation for this decrease. In March 2020 psychologist consultations under the Medicare Benefits Schedule became available via telehealth (AIHW 2023a). It is conceivable that older psychologists in private practice (48% of all psychologists) who would have otherwise retired in 2020 delayed retirement until 2021 as they were able to continue practicing safely during the pandemic.

Although the number of psychologists working in the profession decreased, the overall number of psychologists registered increased from 40,561 in 2020 to 41,791 in 2021.

With the exception of accredited mental health social workers, specialist mental health workers are concentrated in Major cities, with lower rates of workers in Remote and Very remote areas (Spotlight figure). On average, workers in Remote and Very remote areas work more hours per week than their counterparts in Major cities.

According to the Psychology Board of Australia, 14,104 psychologists held an area of practice endorsement in 2021, with Clinical psychology accounted for 71% of endorsements (Psychology Board of Australia 2021a). Almost half (48%) of psychologists were employed in either solo, group or other private practice, while 1 in 10 are employed in schools.

The accredited mental health social worker workforce was the fastest growing of the 5 professions presented here, growing at an average annual rate of 9% from 2017 to 2021. This compares to 6% for mental health occupational therapists, 5% for psychologists, 4% for psychiatrists and 3% for mental health nurses.

Generalist workers

A range of different professions and roles may be included under the broad category of generalist mental health workers. The availability of data varies considerably depending on the accreditation framework of each role. Selected examples are presented here:

General practitioners (GPs) are often first to be engaged to manage mental illness, and act as a gateway to the professions noted above. In 2021, there were around 31,200 GPs working in Australia. According to the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) survey of general practitioners, last conducted in 2015–16, 1 in 8 (12.4%) of all GP encounters were mental health-related (AIHW 2018).

Paramedicine practitioners (paramedics) may be the first-responders to mental health crises. In 2021, there were around 18,700 paramedics working in Australia. Although the proportion of paramedic workload associated with mental illness is difficult to estimate, the National Ambulance Surveillance System, established in 2018, is likely to provide more national data in future.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioners arrange, coordinate and provide health care delivery in Indigenous community health clinics (RANZCP 2016). In 2018–19, an estimated 1 in 4 Indigenous people experience a mental health or behavioural condition (AIHW 2022a), with these professionals recognised as bringing valuable knowledge and skills to the management of mental illness (RANZCP 2016). In 2021, there were around 600 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioners working in Australia.

Social workers assess the social needs, assist and empower people to develop and use the skills and resources needed to resolve problems, and further human wellbeing, human rights, social justice and social development (ABS 2021). There were around 40,000 social workers employed in Australia in 2021 (Jobs and Skills Australia 2021), including 2,670 full time-equivalent positions employed in specialised mental health facilities. Refer to the Specialised mental health care facilities section for more information.

Counsellors and psychotherapists work with people to help them to identify and define their emotional issues through therapies such as talking therapies. There are a variety of different types of counsellors, including drug and alcohol, family and marriage, and rehabilitation. The Australian Counselling Association reports that they have around 9,000 members (ACA 2023). However, as counsellors and psychotherapists are not required to be members of this organisation, the true number is likely to be higher.

Support line volunteers form a vital point of contact for people experiencing distress of crises. There are multiple support lines which provide mental health-related assistance. Some of the largest include:

Lifeline – Approximately 1,000 paid employees and 10,000 volunteers (Lifeline 2022)

Beyond Blue – Approximately 5,000 volunteers (Beyond Blue 2022).

For further information on crisis support lines, refer to the Mental health services activity monitoring section.

Lived experience workers

Lived experience workers, also known as peer or consumer workers, are increasingly recognised as forming a vital component of mental health care. Lived experience workers also include informal carers – family members, friends or others who care for those experiencing mental illness outside of an employment or volunteer setting.

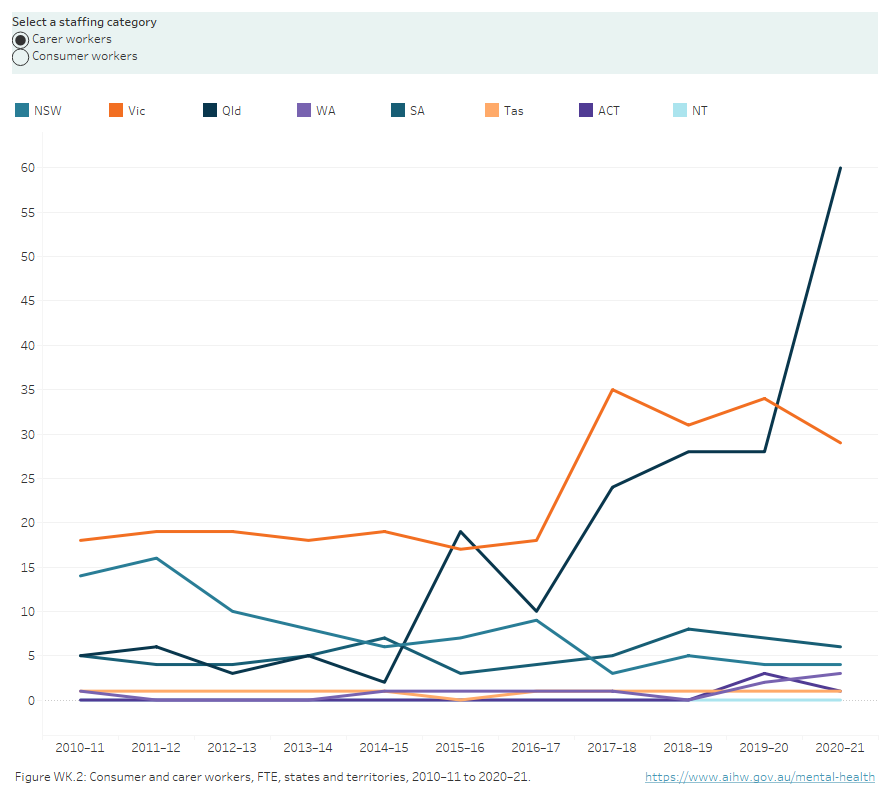

Because of the broad scope of lived experience workers’ engagement with the mental health care sector, there are little reliable data on the total number of lived experience workers in Australia. An exception is in specialised mental health care facilities. In 2020–21, there were 329 FTE paid consumer workers and 103 FTE paid carer workers employed in these facilities (AIHW 2023b), though numbers varied greatly between states and territories (Figure WK.2). The number of consumer workers increased by an average of 27% per year from 2016–17 to 2020–21, while the number of carer workers increased by an average of 25% per year. For further information, refer to the Specialised mental health care facilities section.

Figure WK.2: Consumer and carer workers, FTE and rate, states and territories, 2010–11 to 2020–21

Line chart showing the Full Time Equivalent (FTE), rate per 1,000 paid direct care staff and rate per 100,000 population of consumer and career workers in each state and territory from 2010–11 to 2020–21. Queensland had the highest FTE of carer workers of any jurisdiction in 2020–21 (60). New South Wales had the highest rate of consumer workers (126).

Note: Crude rate is based on the Australian estimated resident population as at 30 June 2021.

Source: Mental health workforce 2021 tables, WK.15

The Mental Health Commission of New South Wales also publishes some data on the peer and carer workforce engaged in that states’ mental health service system. In 2018, there were 100 FTE peer workers employed in NSW public mental health services (MHCNSW 2018).

Where do I go for more information?

You may also be interested in:

National Health Workforce Data Set (NHWDS)

The voluntary Workforce Surveys are administered to all registered health practitioners by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) and are included as part of the registration renewal process. These surveys are used to provide nationally consistent workforce estimates. They also provide data on the type of work done by, and job setting of, health practitioners; the number of hours worked in a clinical or non-clinical role, and in total; and the numbers of years worked in, and intended to remain in, the health workforce. The surveys also provide information on registered health practitioners who are not undertaking clinical work or who are not employed. Response rates for the NHWDS workforce surveys are generally high, although it varies by profession.

The information from the AHPRA workforce surveys, combined with AHPRA registration data items, comprise the NHWDS. A statistical approach is employed to correct for non-responses in creating the NHWDS, replacing missing values with plausible values based on other available information.

Health workforce data is available for public access through the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care’s Health Workforce Data Tool (HWDT) and the data in this publication reflect those extracted using the HWDT as at 12 April 2023. For medical specialists, the numbers are those employed, as specialists, in their primary specialty. As such, there may be differences between the data presented here and that published elsewhere due to different analytical methodologies or data extraction dates.

Further information regarding the health workforce surveys is available at National Health Workforce Dataset.

Mental Health Establishments National Minimum Data Set (MHE NMDS)

Refer to the data source section of the Specialised mental health facilities page for more information.

Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW)

The AASW is the peak professional body for social workers in Australia. Data is collected from members to provide services, including postal address. This may be a place of employment, home residence or post box. Although membership of the AASW for social workers generally is not mandatory, accreditation of mental health social workers is only provided by the AASW. This accreditation enables these social workers to claim certain Medicare-subsidised mental health-specific items under the Medicare Benefits Schedule. Refer to the Medicare-subsidised mental health-specific services section for more information.

Data includes accredited mental health social workers (AMHSWs) as at 30 June 2021. This may include some AMHSWs who have cancelled their accreditation though this number is likely to be small. Clinical hours and telehealth data are derived from a survey of 1,031 AMHSWs (34% response rate) collected from 4 April 2023 to 16 April 2023.

| Key concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Accredited mental health social worker | Accredited Mental Health Social Workers (AMHSWs) have been assessed by the AASW as having specialist mental health expertise. AMHSWs deliver clinical social work services in mental health settings and use a range of evidence-based strategies. They assist individuals with their presenting psychological problems, the associated social and other environmental problems, and improve their quality of life. This may involve individual counselling as well as family and group therapy. Refer to the AASW for more information. |

| Area of practice endorsement | To qualify for an area of practice endorsement, a psychologist must have completed advanced training (a Master's or Doctorate qualification) in the particular area of practice followed by a period of supervised practice. There are nine endorsements, including clinical psychology and forensic psychology (APS 2022). |

| Clinical FTE | Clinical FTE measures the number of standard-hour workloads worked by employed health professionals in a direct clinical role. Clinical FTE is calculated by the number of health professionals in a category multiplied by the average clinical hours worked by those employed in the category divided by the standard working week hours. The NHWDS considers a standard working week to be 38 hours for nurses, psychologists and occupational therapists and 40 hours for psychiatrists. |

| Clinical hours | Clinical hours are the total clinical hours worked per week in the profession, including paid and unpaid work. The average weekly clinical hours is the average of the clinical hours reported by all employed professionals, not only those who define their principal area of work as clinician. Average weekly clinical hours are calculated only for those people who reported their clinical hours (those who did not report them are excluded). |

| Employed | In this report, an employed health professional is defined as one who:

This includes those involved in clinical and non-clinical roles, for example education, research, and administration. ‘Employed’ people are referred to as the ‘workforce’. This excludes those medical practitioners practising psychiatry as a second or third speciality, those who were on extended leave for 3 months or more and those who were not employed. |

| Full-time equivalent | Full-time equivalent (FTE) measures the number of standard-hour workloads worked by employed health professionals. FTE is calculated by the number of health professionals in a category multiplied by the average hours worked by those employed in the category divided by the standard working week hours. In this report, a standard working week for nurses, psychologists and occupational therapists is assumed to be 38 hours and equivalent to 1 FTE. FTE measures for psychiatrists are based on a 40 hour standard working week. |

| Nurse | To qualify for registration as a registered or enrolled nurse in Australia, an individual must have completed an approved program of study (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2019). The usual minimum educational requirement for a registered nurse is a 3 year degree or equivalent. For enrolled nurses the usual minimum educational requirement is a 1 year diploma or equivalent. For the purpose of this section, a mental health nurse is an enrolled or registered nurse that indicates their principal area of work is mental health. In other contexts, mental health nurse may refer to a nurse who has a specific qualification in mental health care instead of or as well as generalist care. Refer to the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia for more information. |

| Occupational therapist | Occupational therapists provide support to people whose health or disability impacts on their day-to-day life and function. For the purpose of this section, a mental health occupational therapist is an occupational therapist who has indicated they have a scope of practice of ‘mental health’. |

| Psychiatrist | A psychiatrist is a medical practitioner who has completed specialist training in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness and emotional problems. Treatment may include prescribing medication, brain stimulation therapies and psychological treatment (RANZCP 2021). To practice as a psychiatrist in Australia, an individual must be admitted as a Fellow of the Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP). Psychiatrists first train as a medical doctor, then undertake a medical internship followed by a minimum of 5 years specialist training in psychiatry (RANZCP 2021). |

| Psychologist | A psychologist is an allied health practitioner who is trained in human behaviour. They may provide diagnosis, assessment and treatment of mental illness through psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioural therapy. The education and training requirement for general (full) registration as a psychologist is a 6 year sequence comprising a 4 year accredited sequence of study followed by an approved 2 year supervised practice program. The 2 year supervised practice program may be comprised of either an approved 2 year postgraduate qualification, a fifth year of study followed by a 1 year internship program or a 2 year internship program (Psychology Board of Australia 2021b). |

| Total hours | Total hours are the total hours worked per week in the profession, including paid and unpaid work. Average total weekly hours are calculated only for those people who reported their hours (that is, those who did not report them are excluded). |

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2021) ANZSCO – Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations, ABS website, accessed 30 June 2022.

ACA (Australian Counselling Association) (2023) About the ACA, ACA website, accessed 28 April 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2023a) Mental health services activity monitoring: quarterly data, Mental Health Online Report, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 5 May 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Specialised mental health care facilities’, Mental Health Online Report, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 28 April 2023.

AIHW (2022) Mental health, Indigenous Mental Health & Suicide Prevention Clearinghouse website, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 30 June 2022.

AIHW (2018) Mental health-related services provided by general practitioners [294KB PDF], AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 11 May 2022.

APS (Australian Psychological Society) (2022) Area of Practice Endorsement pathway, APS website, accessed 27 June 2022.

Beyond Blue (2022) Volunteering opportunities, Beyond Blue website, accessed 12 May 2022.

Cleary A, Thomas N and Boyle F (2020) National Mental Health Workforce Strategy – A literature review of existing national and jurisdictional workforce strategies relevant to the mental health workforce and recent findings of mental health reviews and inquiries, University of Queensland, Brisbane.

Jobs and Skills Australia (2021) Occupation profile – Social Workers, Australian government, accessed 28 April 2023.

Lifeline (2022) Who we are, Lifeline website, accessed 28 April 2023.

MHCNSW (Mental Health Commission of New South Wales) (2018) Indicator 5: Peer Workforce, MHCNSW website, accessed 18 May 2022.

Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (2019) Approved programs of study, Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia website, accessed 30 June 2022.

Psychology Board of Australia (2021a) Registrant data, Reporting period: 01 October 2021 to 31 December 2021, Psychology Board of Australia website, accessed 11 May 2023.

Psychology Board of Australia (2021b) Registration standards, Psychology Board of Australia website, accessed 25 May 2022.

RANZCP (Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists) (2016) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health workers, RANZCP website, accessed 11 May 2022.

RANZCP (2021) What’s a psychiatrist?, RANZCP website, accessed 11 May 2023.

Data in this section were last updated in July 2023.