Health of people with disability

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2022) Health of people with disability, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Health of people with disability. Retrieved from https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-people-with-disability

MLA

Health of people with disability. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 July 2022, https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-people-with-disability

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health of people with disability [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022 [cited 2024 Apr. 19]. Available from: https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-people-with-disability

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2022, Health of people with disability, viewed 19 April 2024, https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-people-with-disability

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Disability and health have a complex relationship – long-term health conditions might cause disability, and disability can contribute to health problems. The nature and extent of a person’s disability can also influence their health experiences. For example, it may limit their access to, and participation in, social and physical activities.

An estimated 1 in 6 people in Australia (17.7% or 4.4 million people) had disability in 2018, including about 1.4 million people (5.7% of the population) with severe or profound disability (ABS 2019a) (see People with disability in Australia, Defining disability).

In general, people with disability report poorer general health and higher levels of psychological distress than people without disability. They also have higher rates of some modifiable health risk factors and behaviours, such as poor diet and tobacco smoking, than people without disability.

This page looks at the health of people with disability, their health risk factors, and the impacts of COVID-19 on the health of people with disability.

Measuring disability

There are many different concepts and measures of disability, making comparisons across different data sources challenging. The AIHW promotes measures based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO 2001), which underpins the disability categories used here.

The data used on this page are primarily from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC) 2018, National Health Survey (NHS) 2017–18 and Household impacts of COVID-19 Survey 2021.

These survey data are supplemented with administrative data from the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

Defining disability

Definitions of disability differ across surveys. The SDAC is the most detailed and comprehensive source of disability prevalence in Australia. To identify disability, the SDAC asks participants if they have at least one of a list of limitations, restrictions or impairments, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least 6 months and that restricts everyday activities.

The limitations are grouped into 10 activities associated with daily living, and a further 2 life areas in which people may experience restriction or difficulty as a result of disability – schooling and employment.

The level of disability is defined by whether a person needs help, has difficulty, or uses aids or equipment with 3 core activities – self-care, mobility, and communication – and is grouped for mild, moderate, severe, and profound limitation. People who ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ need help with one or more core activities, have difficulty understanding or being understood by family or friends, or can communicate more easily using sign language or other non-spoken forms of communication are referred to in this section as ‘people with severe or profound disability’.

The NHS uses the ABS Short Disability Module to identify disability. While this module provides useful information about the characteristics of people with disability relative to those without, it is not recommended for use in measuring disability prevalence.

Disability status in the Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey is captured using a subset of questions from the ABS’ Short Disability Module. For more information, see People with disability: Household impacts of COVID-19.

Unlike the SDAC, the NHS and the Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey do not report on people living in institutional settings, such as aged care facilities. However, these two surveys do provide data on people without disability as well as those with disability, enabling comparisons between the two groups.

Profile of people with disability

The disability population is diverse. It encompasses people with varying types and severities of disability across all parts of Australian society. Knowing how many Australians have disability, and their characteristics, can help us to plan and provide the supports, services and communities that enable people with disability to participate fully in everyday life.

While the number of people with disability in Australia has increased to an estimated 4.4 million in 2018 (up from an estimated 4.0 million in 2009), the prevalence rate has decreased over this period (18.5% of the population in 2009 down to 17.7% in 2018) (ABS 2019a).

Overall, the likelihood of experiencing disability increases with age. This means the longer people live, the more likely they are to experience some form of disability. More information on the prevalence of disability is provided in the AIHW report People with disability in Australia, Prevalence of disability.

General health

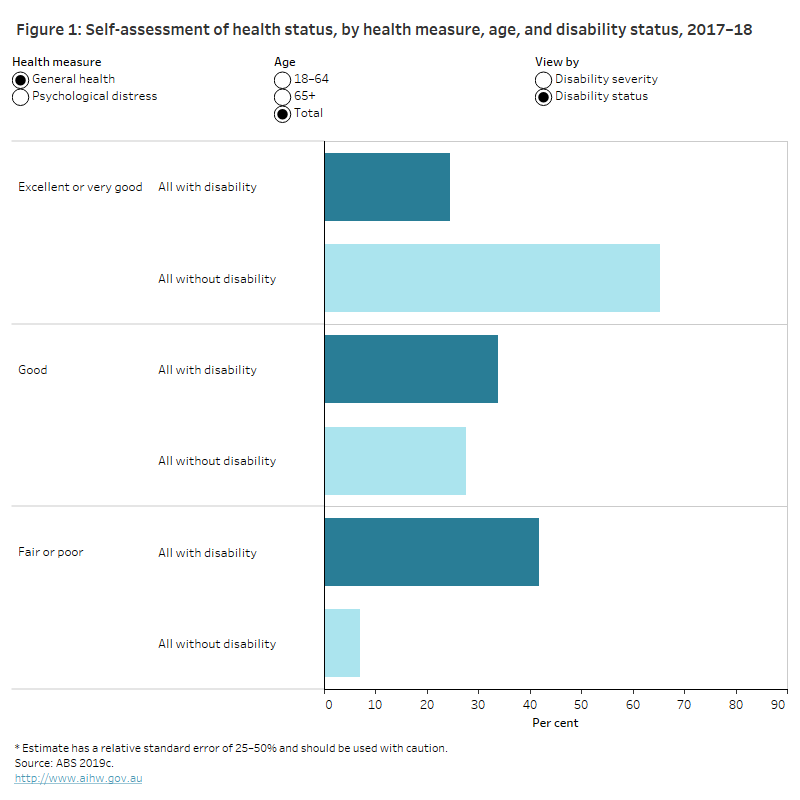

Adults with disability are more likely to report poorer general health. In 2017–18:

- Adults with disability were less likely to assess their health as ‘very good or excellent’ than adults without disability (24% compared with 65%) (ABS 2019c ).

- Adults with severe or profound disability (62%), are almost 9 times as likely as adults without disability (7.0%), and almost twice as likely as adults with other disability (37%) to assess their health as fair or poor (ABS 2019c).

See People with disability in Australia, Health status for more information.

Mental health

Mental health conditions can be both a cause and an effect of disability, and often involve activity limitations and participation restrictions beyond the ‘core’ areas of communication, mobility and self-care – for example, in personal relationships.

Over 4 in 10 (42%) people with severe or profound disability, and 33% of people with other forms of disability, self-reported anxiety-related problems in the 2017–18 NHS. This compares with 12% of people without disability (ABS 2019b).

An estimated 36% of people with severe or profound disability self-reported that they had mood (affective) disorders such as depression, compared with 32% of people with other forms of disability, and 8.7% of people without disability (ABS 2019b).

Self-reported psychological distress is an important indication of the overall mental health of a population. Higher levels of psychological distress indicate that a person may have, or is at risk of developing, mental health issues. Adults with disability are more likely (32%) to experience high or very high levels of psychological distress than adults without disability (8.0%). This is particularly true for adults with severe or profound disability (40%) (ABS 2019c) (Figure 1).

This graph shows that people with disability are less likely than those without disability to report their general health as excellent or very good (24% verses 65%), and their psychological distress level as low (42% verses 70%). This trend is true regardless of age.

See People with disability in Australia, Health status for more information.

Main conditions of people with disability

For about 3 in 4 (77%) Australians with disability, their main form of disability (that is their main condition or the one causing the most problems) is physical. Musculoskeletal disorders were the most commonly reported (30%) physical disorders, and include conditions such as arthritis and related disorders (13%), and back problems (13%) (ABS 2019a).

Mental or behavioural disorders were reported as the main form of disability by almost one-quarter (23%) of people with disability. The most common mental or behavioural disorders were psychoses and mood disorders (7.5%), and intellectual and development disorders (6.5%) (ABS 2019a).

For more information on the prevalence of disability within specific health conditions, see People with disability in Australia, Chronic conditions and disability.

Health risk factors

People with disability generally have higher rates of some modifiable health risk factors and behaviours than people without disability. But there can be particular challenges for people with disability in modifying some risk factors, for example, where extra assistance is needed to achieve a physically active lifestyle, or where medication increases appetite or affects drinking behaviours.

In 2017–18, compared with people without disability, people with disability were more likely to report:

- an insufficient level of physical activity in the last week

- that they smoked daily

- being overweight or obese

- eating insufficient serves of fruit and vegetables per day (Figure 2).

See People with disability in Australia, Health risk factors and behaviours for more information.

This graph shows that people with disability are more likely than those without disability to have higher health risks for the factors: Physical activity (72% verses 52%), smoking (18% verses 12%), body weight (72% verses 55%) and diet (47% verses 41%), but are also less likely to have a higher health risk in alcohol consumption (14% verses 16%). This trend is true regardless of age.

People with disability and COVID-19

This section looks at the impact of COVID-19 on the health of people with disability compared to people without disability. It draws on the ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 Surveys conducted between April 2020 and June 2021, and data on the subset of the population who are NDIS participants. Note that population-wide administrative data sources about COVID-19 infections, vaccinations and deaths do not include information about disability status. For information about the impact of COVID-19 on the whole population see ‘Chapter 1 The impact of a new disease: COVID-19 from 2020, 2021 and into 2022’ in Australia’s health 2022: data insights.

COVID-19 vaccinations

Many people with disability are at an increased risk of severe illness from COVID-19, both due to direct impacts of any underlying chronic conditions and to possible challenges with maintaining physical distancing and applying other COVID-19 precautions (Department of Health 2021b). For these reasons, people with disability were one of the priority groups to become eligible for COVID-19 vaccination in the early stages of Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout strategy (Department of Health 2021a).

Based on the Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey data, in June 2021, adults with disability were more likely than those without disability to report:

- having received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (46% of adults with disability compared with 28% of adults without disability)

- being motivated to get a vaccine because:

- it was recommended by a general practitioner (GP) or other health professional (38% compared with 28%)

- they had health conditions which made them more vulnerable to COVID-19 (28% compared with 13%) (ABS 2021b).

See more information on COVID-19 cases and vaccinations in People with disability in Australia, Experiences of people with disability during COVID-19 pandemic and ‘Chapter 1 The impact of a new disease: COVID-19 from 2020, 2021 and into 2022’ in Australia’s health 2022: data insights.

COVID-19 cases among NDIS participants

The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) collaborated with other government agencies (including the Department of Social Services, the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission, Services Australia, and state and territory governments) to support NDIS participants through the pandemic.

As of May 2022:

- A total of 12,721 COVID-19 cases had been reported among NDIS participants.

- There were 74 COVID-19 related deaths (0.6% of NDIS participant cases) (Department of Health 2022).

Self-assessed health

Based on the Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, in December 2020, results for self-assessed excellent or very good physical health for adults with disability compared with those without disability (25% and 64% respectively) were broadly similar to previous results for general health from the 2017–18 National Health Survey (see ‘General health’).

Results have varied throughout the COVID-19 pandemic both for adults with and without disability. However, between December 2020 and May 2021, the proportion of adults with disability reporting excellent or very good physical health was consistently lower than for those without disability (25% compared with 64% in December 2020, 21% compared with 50% in January 2021 and 29% compared with 55% in May 2021).

Psychological distress

In November 2020, as well as March and June 2021, the Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey collected information about negative events or feelings experienced by respondents in the 4 weeks leading up to the interview. This allows identification of levels of psychological distress of adults aged 18 years and over.

Adults with disability were consistently more likely to experience high or very high levels of psychological distress than those without disability (34% compared with 16% in November 2020, 30% compared with 16% in March 2021 and 29% compared with 17% in June 2021).

For more information on experiences of people with disability during the COVID-19 pandemic and their physical and mental health status, see People with disability in Australia, Experiences of people with disability during COVID-19 pandemic.

Use of mental health or support services

Adults with disability were more likely than those without disability to report that they had used at least one mental health or support service between March 2020 and April 2021 (29% of adults with disability, compared with 13% of those without disability).

The most common services used in April 2021 were (more than one service could be reported):

- GP for mental health (20% for adults with disability compared with 8.2% for those without disability)

- psychologist, psychiatrist or other mental health specialist (19% compared with 7.1% for those without disability) (ABS 2021a).

See more information on experiences of people with disability during the COVID-19 pandemic and their use of health services in People with disability in Australia, Experiences of people with disability during COVID-19 pandemic.

Use of telehealth services

In April 2021, adults with disability (21%) were more likely than those without disability (12%) to report having had a telehealth consultation in the previous 4 weeks. For adults with disability, this was a decrease from November 2020 (30%), while remaining similar for those without disability (14% in November 2020) (ABS 2020, 2021a).

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on the health of people with disability, see:

- People with disability in Australia

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: summary of findings, 2018

- ABS National Health Survey: first results, 2017–18

- National Disability Insurance Scheme

- Household impacts of COVID-19 Survey 2021

Visit Disability for more on this topic.

References

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2019a) Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: summary of findings, 2018, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 14 April 2022.

ABS (2019b) Microdata: National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–18, AIHW analysis of ABS TableBuilder, accessed February 2020.

ABS (2019c) Microdata: National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–18, AIHW analysis of ABS microdata, accessed April 2019.

ABS (2020) Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, November 2020, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 20 April 2022.

ABS (2021a) Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, April 2021, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 20 April 2022.

ABS (2021b) Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, June 2021, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 20 April 2022.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2022). People with disability in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government.

Department of Health (2021a) COVID-19 vaccination – Australia's COVID-19 vaccine national roll-out strategy, Department of Health website, accessed 20 April 2022.

Department of Health (2021b) For people with a disability | Australian Government Department of Health, Department of Health website, accessed 20 April 2022.

Department of Health (2022) Coronavirus (COVID-19) case numbers and statistics, Department of Health, accessed 2 May 2022.

NDIA (National Disability Insurance Agency) (2021) COAG Disability Reform Council, quarterly report, 30 June 2021, NDIA, Australian Government, accessed 14 April 2022.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2001) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, WHO, accessed 14 April 2022.