Overcrowding

Key findings

- In 2016, around 18,900 children (0.4%) aged 0–14 were living in overcrowded housing on Census night.

- The proportion of children living in overcrowded housing remained relatively stable between 2006 and 2016.

- Children living in low socioeconomic areas were 12 times as likely to be living in an overcrowded situation (1.2%) as those from high socioeconomic areas (0.1%).

Safe, secure and stable access to room for study, play and undisrupted sleep is critical for children’s health and development. However, a number of children live in overcrowded dwellings—homes that are too small for the size and composition of the household—limiting their access to such space.

At increased risk of experiencing overcrowding are:

- families with low household incomes due to the high cost of housing in many parts of Australia (Easthope et al. 2017)

- parents and children leaving family and domestic violence who are in situations where access to financial resources and social support is limited (Mission Australia 2019).

Overcrowding extends beyond 2 siblings sharing a room. It is characterised by uncomfortable or irregular sleeping arrangements, with multiple children of different ages and sexes sharing bedrooms, parents forced to share bedrooms with their children, and single adults or multiple couples sharing a room. Families often resort to sleeping in living and dining rooms in the absence of space (Shelter 2005). For more information on how overcrowding is defined, see Box 1.

Overcrowding has been associated with increased risk of emotional and behavioural problems and reduced school performance, likely due to disrupted sleep, lack of space to study and the impact of noise levels on concentration (Solari & Mare 2012). Lack of privacy can impact family relationships, leading to family conflict. It can contribute to childhood mental health problems including anxiety, depression and stress (Solari & Mare 2012). Distress over lack of control of living conditions is frequently reported by adults living in crowded dwellings (Lowell et al. 2018).

Overcrowding can also impact children’s physical health, with asthma frequently reported by families experiencing overcrowding (Shelter 2005; Solari & Mare 2012).

Overcrowding is higher among Indigenous households and therefore can impact children’s health, including ear, skin and other infections. Overcrowding can also compromise children’s access to adequate nutrition, with flow-on effects to their health and development (Lowell et al. 2018; Thurber et al. 2017).

Box 1: Data source and definition of overcrowding

Data on overcrowding come from the ABS Census of Population and Housing. The Census is collected by the ABS every 5 years with the most recent data available for 2016. The 2016 Census collected information on welfare-related topics, including overcrowding.

In this section, households are considered overcrowded if they are estimated to require 3 extra bedrooms according to the Canadian National Occupancy Standard (CNOS) (ABS 2018).

Persons living in overcrowded dwellings are considered a marginal housing group and may be at risk of homelessness. Persons living in severely overcrowded situations (households requiring 4 or more extra bedrooms) are considered homeless and are not included here. They are instead included in homelessness estimates.

In 2016, approximately 40% of children living in households requiring 3 or more extra bedrooms were considered homeless.

The ABS definition of overcrowding differs from that used in National Housing and Homelessness Agreement reporting and the Report on Government Services, where overcrowding is defined as households requiring 1 or more additional bedrooms (SCRGSP 2019).

Canadian National Occupancy Standard

The CNOS assesses the bedroom requirements of a household based on these criteria:

- There should be no more than 2 persons per bedroom.

- Children less than 5 years of age of different sexes may reasonably share a bedroom.

- Children 5 years of age or older of opposite sex should have separate bedrooms.

- Children less than 18 years of age and of the same sex may reasonably share a bedroom.

- Single household members 18 years or older should have a separate bedroom, as should parents or couples (AIHW 2017).

Overcrowding can be assessed at household level or individual level.

This section reports on overcrowding at individual level.

How many children live in overcrowded housing?

In 2016, around 18,900 children aged 0–14 lived in overcrowded housing, a proportion of 0.4%.

- There were no differences in the proportion of boys and girls living in overcrowded housing (both 0.4%).

- Rates were the same across age groups, with children aged 0–4, 5–9 and 10–14 all equally as likely to live in overcrowded housing (all 0.4%).

- Children aged 0–14 were slightly over-represented in overcrowded living situations, making up nearly one-quarter (23%) of all people living in overcrowded housing while comprising just under one-fifth (19%) of the Australian population.

Have rates of overcrowding improved over time?

The proportion of children aged 0–14 living in overcrowded housing remained relatively stable between 2006 (0.3% or 13,100) and 2016 (0.4% or 18,900).

Are rates of overcrowding the same for everyone?

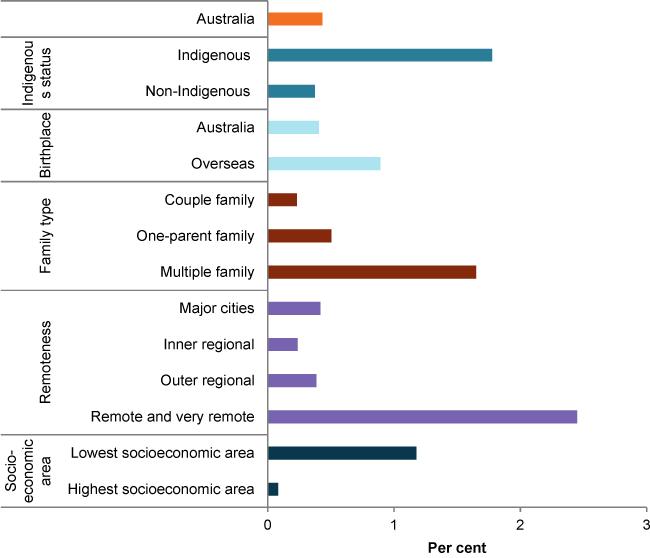

In 2016, the proportion of children aged 0–14 living in overcrowded housing varied by population group.

Children from households with multiple families were more likely living in an overcrowded situation (1.6% or 8,100) than children in 1-parent families (0.5% or 3,300) and couple families (0.2% or 7,400).

More children were living in an overcrowded situation in Remote and very remote areas (2.4% or 2,600) than in Outer regional (0.4% or 1,500), Major cities (0.4% or 12,900) and Inner regional (0.2% or 1,900) areas.

Children living in the lowest socioeconomic areas were also more likely than those as in the highest socioeconomic areas to be living in an overcrowded situation (1.2% or 9,700 compared with 0.1% or 760).

Differences were also evident between children born overseas and children born in Australia (0.9% or 3,300 compared with 0.4% or 15,300), and between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and non-Indigenous children (1.8% or 3,900 compared with 0.4% or 14,700) (Figure 1). However, rates of overcrowding among Indigenous children showed a positive change between 2006 and 2016, decreasing from 2.5% to 1.8%.

Figure 1: Proportion of children aged 0–14 living in overcrowded housing, by priority population group, 2016

Chart: AIHW. Source: ABS 2018.

Data limitations and development opportunities

Limitations to the way family relationships are coded in the Census can result in the misclassification of relationships, especially for large households with complex family relationships or multiple families. If relationships are incorrectly recorded, households including more than 1 couple may look like crowded group households as single adults require their own bedroom while couples can share a bedroom under the Canadian National Occupancy Standard. This may inflate the number of children recorded as living in overcrowded housing. The ABS has recently started exploring the definitions of family across its full suite of surveys and data sources.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on:

- Indigenous children and overcrowding, see: Indigenous children.

- overcrowding by states and territories, see: Children’s Headline Indicators.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2018. Census of Population and Housing. ABS cat. no. 2049.0. Canberra: ABS.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2017. Canadian National Occupancy Standard. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 26 August 2010.

Easthope H, Stone W & Cheshire L 2017. The decline of ‘advantageous disadvantage’ in gateway suburbs in Australia: The challenge of private housing market settlement for newly arrived migrants. Urban Studies 0:0042098017700791.

Lowell A, Maypilama L, Fasoli L, Guyula Y, Guyula A, Yunupiju M et al. 2018. The 'invisible homeless' - Challenges faced by families bringing up their children in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. BMC Public Health 18(1):1–14.

Mission Australia 2019. Out of the shadows—Domestic and family violence: A leading cause of homelessness in Australia. Sydney: Mission Australia.

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2019. Report on Government Services; Part G: Housing and Homelessness. Productivity Commission. Viewed 20 September 2019.

Shelter 2005. Full house? How overcrowded housing affects families. London: Shelter.

Solari CD & Mare RD 2012. Housing crowding effects on children’s wellbeing. Social Science Research 41:464–476.

Thurber KA, Banwell C, Neeman T, Dobbins T, Pescud M, Lovett R et al. 2017. Understanding barriers to fruit and vegetable intake in the Australian longitudinal study of Indigenous children: a mixed-methods approach. Public Health Nutrition 20(5):832–47.