Child abuse and neglect

Data updates

25/02/22 – In the Data section, updated data related to child abuse and neglect are presented in Data tables: Australia’s children 2022 – Justice and safety. The web report text was last updated in December 2019.

Key findings

- In 2017–18, approximately 26,400 children aged 0–12 had 1 or more child protection notifications substantiated (excluding New South Wales as data were not available).

- Children aged under 1 were around twice as likely as other age groups to have at least 1 child protection substantiation.

- Emotional abuse was the most commonly reported primary abuse type for substantiations (59%).

- More than one-third (35%) of children aged 0–12 who had at least 1 substantiation were in the lowest socioeconomic group. The highest socioeconomic group accounted for 6%.

While most children in Australia grow up in families that provide them with environments where they are safe, happy and healthy, some children are the subject of maltreatment (any abuse and/or neglect) (COAG 2009).

Child abuse and neglect is a broad term covering any intentional and non-intentional behaviours by parents, caregivers, or other adults considered to be in a position of responsibility, trust or power that results in a child being harmed physically or emotionally (AIFS 2014; WHO 1999).

For details on the types of child maltreatment see Box 1.

Box 1: Defining child maltreatment

Child maltreatment includes physical, sexual and emotional abuse, and neglect inflicted upon a child by a person responsible for their care and wellbeing.

Physical abuse includes any non-accidental physical act inflicted upon a child that causes harm.

Sexual abuse includes any act that exposes the child to, or involves the child in, sexual processes beyond their understanding, or contrary to accepted community standards.

Emotional abuse includes any act that results in the child suffering significant emotional deprivation or trauma, including suffering caused by exposure to family and domestic violence.

Neglect includes any serious act or omission that, within the bounds of cultural tradition, constitutes a failure to provide conditions essential for the healthy physical and emotional development of a child (AIHW 2019a).

The 2016 ABS Personal Safety Survey (PSS) estimates that about 2.5 million Australian adults (13%) experienced physical and/or sexual abuse during childhood (ABS 2019). Those who experienced both physical and sexual abuse were younger on average at the time of the first incident than those who experienced physical assault only or sexual assault only (average age of 6.8 years compared with 8.1 and 8.8 years, respectively).

The majority of adults who reported childhood physical abuse only (97%) and sexual abuse only (86%) knew the perpetrator, with 81% of those who experienced physical abuse only being abused by a family member. These cases would be considered family violence.

Child abuse and neglect can have a wide range of significant adverse impacts on a child’s development and later outcomes, including but not limited to:

- reduced social skills

- poor school performance

- impaired language ability

- higher likelihood of criminal offending

- negative physical health outcomes

- mental health issues such as eating disorders, substance abuse, depression and suicide (ABS 2019; AIFS 2014).

Recent Australian linkage projects have found that children who have contact with the child protection system were more likely than other children to have contact with the juvenile justice system and homelessness services, and to have lower literacy and numeracy achievement than all students (AIHW 2015, 2016, 2017).

Further, analyses on the South Australian Early Childhood Data Project—a multi-source linked data asset—indicated that children who had contact with child protection agencies were more likely to have developmental vulnerabilities on school entry compared with children who did not have contact, and that vulnerability increased with level of contact. Children who had experienced out-of-home care were almost 1.5 times as likely to have developmental vulnerabilities at age 5 compared with those who had a notification to a child protection department only (Pilkington et al. 2019). See also, Children under youth justice supervision, Homelessness and Education.

From a health perspective, 3 conditions directly linked to child abuse and neglect—anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and suicide and self-inflicted injuries—were estimated to have been responsible for 0.5% of all deaths and 2.2% of the burden of disease and injury in 2015 (AIHW 2019b). More specifically, it was estimated that there would have been 26% less suicide and self-inflicted injuries, 20% less depressive disorders and 27% less anxiety disorders in 2015 if no one in Australia had ever experienced child abuse and neglect during childhood (AIHW 2019b).

In the absence of comprehensive national data on the prevalence of child abuse and neglect in Australia, this snapshot focuses on children who have been in contact with the child protection system, especially those where a notification to a child protection department has been substantiated. A substantiation indicates cases where there is sufficient reason to believe the child has been, is being, or is likely to be harmed in some way (Box 2). These data are sourced from the Child Protection National Minimum Dataset (CP NMDS) and are likely to underestimate the prevalence of child abuse and neglect, given that not all cases may come to the attention of child protection authorities (Besharov 2005; Matthews et al. 2015). In addition, there are some definitional differences between states and territories which may impact the comparability of substantiation data (see Technical notes below).

Box 2: Measuring child abuse and neglect

For this snapshot, children are considered to have been the subject of child abuse and/or neglect if a child protection notification has been investigated and subsequently substantiated. Not all notifications are investigated and not all investigations are substantiated.

Notifications consist of contacts made to an authorised department by people or other bodies alleging child abuse or neglect, child maltreatment, or harm to a child. A notification can only involve 1 child. Where it is claimed that 2 children have been abused, neglected or harmed, this is counted as 2 notifications. Where there is more than 1 notification about the same event involving a child, this is counted as 1 notification. Where there is more than 1 notification for the same child relating to different events, these are counted as separate notifications.

Investigation is the processes whereby the relevant department obtains more detailed information about a child who is the subject of a notification. Departmental staff assess the harm or degree of harm to the child, and their protective needs. An investigation includes sighting or interviewing the child where it is practical to do so.

Substantiations are notifications where an investigation concluded there was reasonable cause to believe the child had been, was being, or was likely to be, abused, neglected or otherwise harmed. Substantiations might also include cases where there is no suitable caregiver, such as children who have been abandoned or whose parents are deceased (AIHW 2019a).

Children and the child protection system

In 2017–18, for states and territories with available data (excluding New South Wales), around 116,000 children aged 0–12 had 1 or more notifications to child protection authorities, alleging child abuse or neglect. These children accounted for around 173,000 notifications during this time, of which approximately 40% were investigated. The remaining notifications were dealt with by other means, such as referral to a support service.

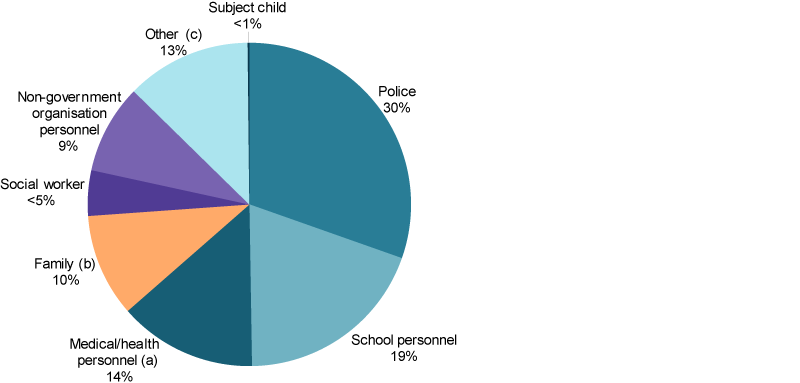

The most common-known source of notification for those investigated cases was:

- police (30%)

- school personnel (19%)

- medical/health personnel (14%) (Figure 1).

Cases where the child involved was the source of notification accounted for less than 1%.

Figure 1: Investigations, by source of notification, 2017–18 (%)

- Medical/health personnel include medical practitioners, hospital and other health personnel.

- Family includes parent/guardian, sibling and other relative.

- Other category includes friend/neighbour, departmental officer, child care personnel and cases where the source of notification was anonymous and may include the person responsible.

Note: This table excludes children for whom source of notification was unknown.

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW Child Protection National Minimum Data Set.

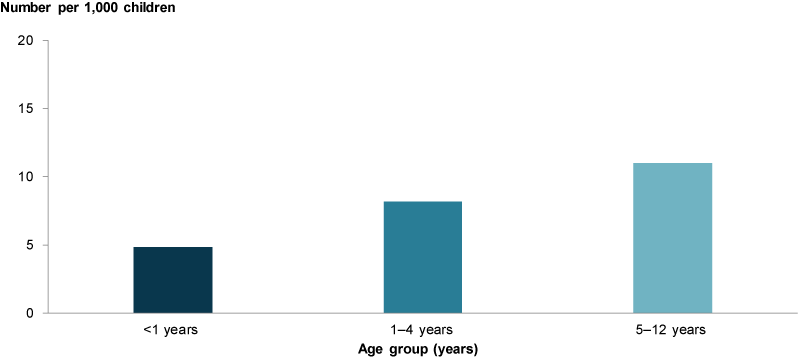

How many children have child protection notifications substantiated?

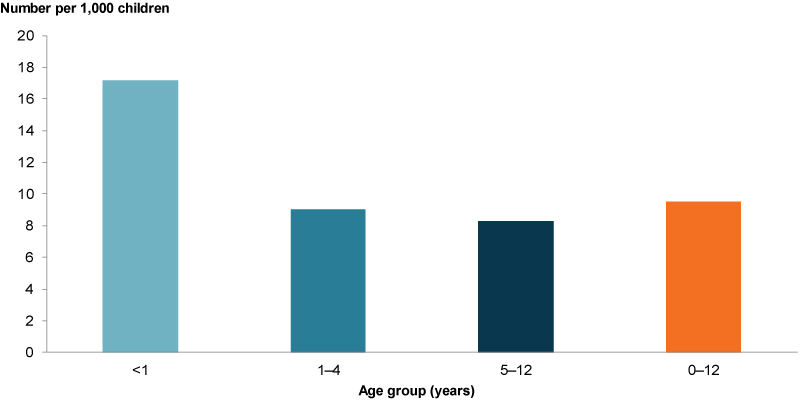

For states and territories with available data (excluding New South Wales), approximately 26,400 children aged 0–12 had 1 or more child protection notifications substantiated in 2017–18. This equates to a rate of 9.5 per 1,000 children aged 0–12 (Figure 2).

Children aged under 1 were around twice as likely to have at least 1 child protection substantiation as children aged 1–4 or 5–12 (17 per 1,000 children compared with 9.0 and 8.3 per 1,000 children, respectively). Substantiation rates were similar for boys and girls.

Figure 2: Children aged 0–12 with 1 or more substantiations, by age group, 2017–18

Note: Excludes New South Wales, which implemented a new client management system in 2017–18 and provided limited data. New South Wales is working to improve the quality and completeness of data for future reporting.

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW Child Protection National Minimum Data Set.

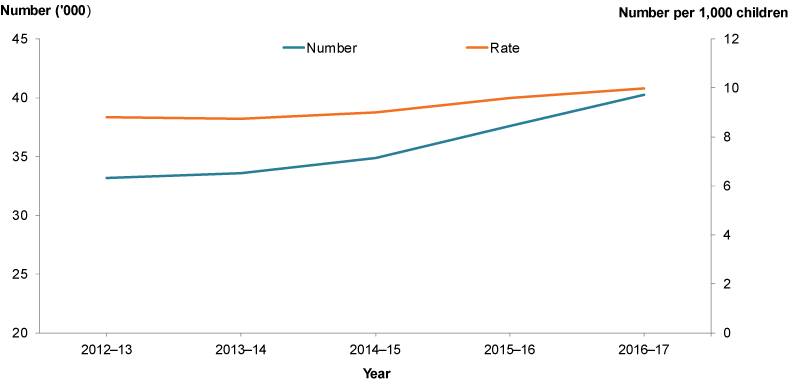

Between 2012–13 and 2016–17, there was a steady increase in both the number and rate of children aged 0–12 who were the subject of 1 or more substantiations (Figure 3).

The number of children who had a substantiation rose from around 33,200 in 2012–13 to around 40,200 in 2016–17. This represents rates of 8.8 per 1,000 children and 10.0 per 1,000 children, respectively.

Figure 3: Children aged 0–12 with 1 or more substantiation, 2012–13 to 2016–17

Note: New South Wales substantiation data are unavailable for 2017–18. As a result, 2017–18 data

have been excluded from time series analyses to maintain comparability.

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW Child Protection National Minimum Data Set.

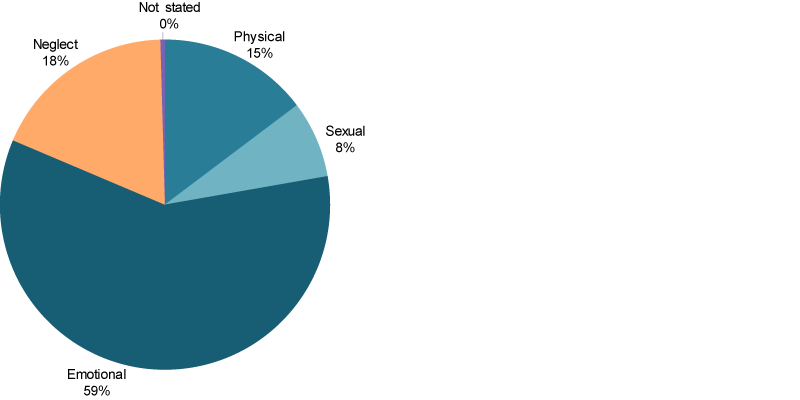

What types of abuse and neglect are being reported?

The most commonly reported primary abuse type for substantiations in 2017–18 was emotional abuse (59% of substantiations) (Figure 4). This was true for both Indigenous (50%) and non-Indigenous children (64%) in states and territories with available data (excluding New South Wales and Tasmania). Most abuse and neglect cases are likely considered family violence.

Figure 4: Children aged 0–12 who were the subjects of substantiations, by type of abuse, 2017–18

Note: Excludes data for New South Wales due to data quality and completeness issues.

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW Child Protection National Minimum Data Set.

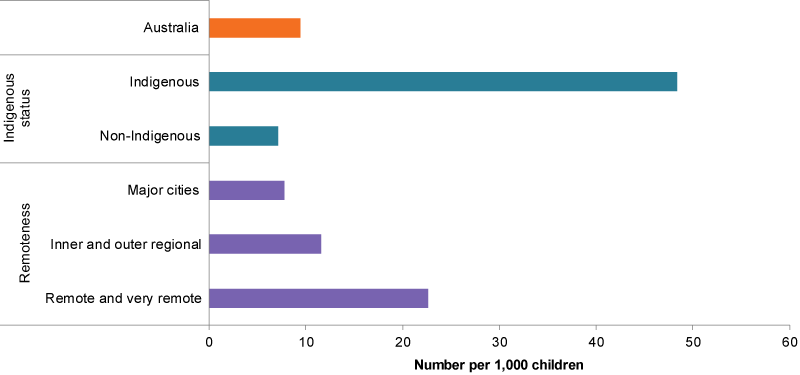

Do rates of substantiations vary by population group?

The rate of children aged 0–12 who had at least 1 substantiation in the 2017–18 year varied between population groups (Figure 5).

The rate of children who had at least 1 substantiation increased with remoteness of the child’s residence. There was a three-fold difference between rates for Major cities and Remote and very remote areas (7.8 per 1,000 children compared with 23 per 1,000 children).

Based on states and territories where data were available (excluding New South Wales and Tasmania), Indigenous children were more likely than non-Indigenous children to have had a substantiation in 2017–18 (48 per 1,000 children compared with 7.2 per 1,000).

Rates for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children increased between 2012–13 and 2016–17 (includes data from all states and territories).

Figure 5: Children aged 0–12 with 1 or more substantiation, by select population groups, 2017–18

Notes

- Excludes data for New South Wales due to data quality and completeness issues in 2017–18.

- Results disaggregated by Indigenous status exclude data from Tasmania due to data quality and completeness issues in 2017-18.

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW Child Protection National Minimum Data Set.

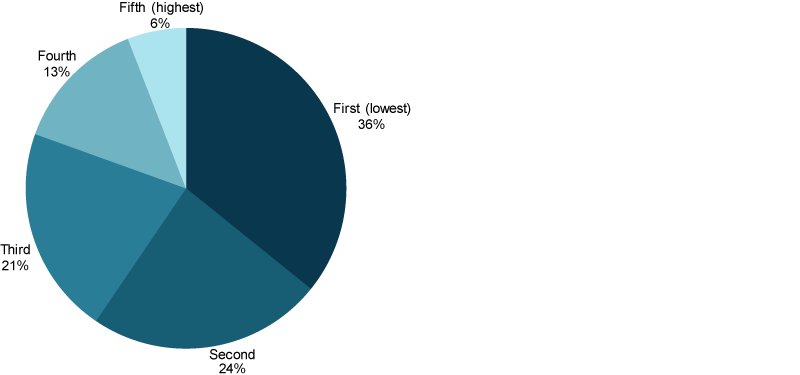

More than one-third (36%) of children aged 0–12 who had at least 1 substantiation were in the lowest socioeconomic group. Those in the highest socioeconomic groups accounted for 6% in 2017–18 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Children with 1 or more substantiation, by socioeconomic group, 2017–18 (%)

Notes:

- Excludes children for whom socioeconomic area was unable to be established.

- Excludes data for New South Wales due to data quality and completeness issues.

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW Child Protection National Minimum Data Set.

How many children are on care and protection orders?

Around 39,700 children aged 0–12 were on a care and protection order in Australia on 30 June 2018 (Box 4). This equates to a rate of 9.6 per 1,000 children.

Box 3: Defining and measuring care and protection orders

Care and protection orders are legal orders or arrangements that give child protection departments partial responsibility for a child’s welfare. For this report, children are counted only once, even if they were admitted to, or discharged from, more than 1 order, or were on more than 1 order at 30 June of given year.

There were less children aged under 1 on care and protection orders than older children at 30 June 2018 (4.8 per 1,000 compared with 11.0 per 1,000 children aged 5–12) (Figure 7). This reflects the fact that children aged under 1 had less time than older children to be placed on an order by 30 June.

Figure 7: Children on a care and protection order at 30 June 2018

Note: Indigenous children were more likely on care and protections orders than non-Indigenous children (66.8 per 1,000 children compared with 6.3 per 1,000 children) (excludes Tasmania).

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW Child Protection National Minimum Data Set.

Data limitations and development opportunities

As there are currently no comprehensive national data on the prevalence of child abuse and neglect, including re-occurrence, proxy data from child protection service agencies are used. These data are likely to underestimate child abuse and neglect in Australia as they do not include cases of child abuse and neglect that go unreported to child protection authorities. Further, variations between jurisdictions in recorded cases of child abuse or neglect reflect the legislation, policies and practices in each jurisdiction, rather than a true variation in the levels of recorded abuse and neglect. (See, Technical notes below).

The sensitive collection of information directly from children on their recent experience of abuse and neglect would be an important supplement to the data already collected. The First national study of child abuse and neglect in Australia, being conducted from 2019–2023, will provide a retrospective view of maltreatment in younger years by respondents aged 16 and over (QUT 2019). However, recent research suggests that large discrepancies exist between reporting recent or ongoing childhood maltreatment as a child and recalling childhood maltreatment as an adult (Baldwin et al. 2019).

Where do I find more information?

For more information on:

- Child protection substantiations for Indigenous children, see: Indigenous children

- child protection substantiations, see: Child abuse and neglect in Children’s Headline Indicators and Child protection substantiations in the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children

- child protection data, see: Child Protection National Minimum Data Set (CP NMDS), Child protection Australia 2017–18 and Report on Government Services, Chapter 16: Child Protection Services.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2019. Personal safety, Australia, 2016: Characteristics and outcomes of Childhood abuse. ABS cat. no. 4906.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 25 June 2019.

AIFS (Australian Institute of Family Studies) 2014. Effects of child abuse and neglect for children and adolescents. Melbourne: AIFS. Viewed 22 May 2019.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2015. Educational outcomes for children in care: linking 2013 child protection and NAPLAN data. Cat. no. CWS 54. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2016. Vulnerable young people: interactions across homelessness, youth justice and child protection—1 July 2011 to 30 June 2015. Cat. no. HOU 279. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019a. Child protection Australia: 2017–18. Child welfare series no. 70. Cat. no. CWS 65. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019b. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story. Cat. no. FDV 3. Canberra: AIHW.

Baldwin R, Reuben A & Newbury J 2019. Agreement between prospective and retrospective measures of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 76(6):584–593.

Besharov D 2005. Overreporting and underreporting are twin problems. In Loseke DR, Gelles RJ & Cavanaugh MM (eds). Current controversies on family violence. California: Sage.

COAG (Council of Australian Governments) 2009. Protecting children is everyone’s business: National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020. Canberra: COAG. Viewed 22 May 2019.

Mathews B, Bromfield L, Walsh K & Vimpani G 2015. Child abuse and neglect: a socio-legal study of mandatory reporting in Australia—report for the Northern Territory Government. Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology. Viewed 22 May 2019.

Pilkington R, Montgomerie A, Grant J, Gialamas A, Malvaso C, Smother L et al. 2019. An innovative linked data platform to improve the wellbeing of children: The South Australian Early Childhood Data Project. In Australia’s welfare 2019. Canberra: AIHW.

QUT (Queensland University of Technology) 2019. First national study of child maltreatment. Brisbane: QUT. Viewed 8 April 2019.

WHO (World Health Organization) 1999. Report of the consultation on child abuse prevention, 29–31 March 1999. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 22 May 2019.

AIHW Child Protection National Minimum Data Set

- National child protection data are based on those cases reported to departments responsible for child protection, so are likely to understate the true prevalence of child abuse and neglect across Australia. Further, notifications made to other organisations, such as the police or non-government welfare agencies, are included only if these notifications were also referred to departments responsible for child protection.

- This section focuses on substantiations rather than notifications in order to minimise the impact of data comparability issues. While there may be some differences between jurisdictions regarding the definition of a substantiation, it is generally accepted that there is enough commonality between the states and territories to use substantiations as the primary method for reporting on child abuse and neglect.

- There are a number of issues of comparability that exist when considering data on child protection notifications, investigations and substantiations, primarily these issues arise from differences in jurisdictional legislation, policies and definitions.

- In Tasmania, Indigenous status was not cross-checked with data from other databases in 2017–18. This resulted in a higher proportion of clients with an unknown Indigenous status than in previous years. Due to the impact this had on the reliability of data disaggregated by Indigenous status, Tasmania were excluded from analyses disaggregated at this level for the 2017–18 year. Tasmania has been working to rectify this issue and will revise this data in the future. As a result, this report may not match data in future AIHW publications.

- Instances of alleged abuse or neglect by family members (other than parents/guardians) and non-family members are generally included in the count of notifications if the notification was referred to the state and territory departments responsible for child protection.

- The Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage, used here as a measure of socioeconomic position, broadly assesses ‘people’s access to material and social resources, and their ability to participate in society’. For more information see Child Protection Australia, Appendix B.

- For some states and territories, counts of investigations and substantiations only counted where there has been a finding or allegation of a failure to protect by the parent or guardian. For more information, see Appendix C of the online publication of Child protection Australia: 2017–18 (PDF, 435kB).

For more information, see Methods.