Bullying

Data updates

25/02/22 – In the Data section, updated data related to bullying are presented in Data tables: Australia’s children 2022 – Justice and safety. The web report text was last updated in December 2019.

Key findings

- Data from the Longitudinal (LSAC) in 2016 shows that 7 in 10 children aged 12–13 experienced at least 1 bullying-like behaviour within a year.

- According to the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) 2015, 1 in 5 Year 4 students experience bullying on a weekly basis.

- 1 in 4 children aged 8–12 who completed the eSafety Commissioner’s Youth Digital Participation Survey showed experienced unwanted contact and content while online.

- Data from LSAC in 2016 found that almost half (46%) of children aged 12–13 who experienced at least 1 bullying-like behaviours within a year also used bullying-like behaviours against another child.

Bullying refers to any intentional and repeated behaviour which causes physical, emotional or social harm to a person who has, or is perceived to have, less power than the person who bullies (Australian Education Authorities 2019; Kids Helpline 2019; Australian Human Rights Commission 2012).

Bullying is a complex issue. It comes in many forms, occurs in various settings, and affects many population groups (Australian Education Authorities 2019; ReachOut Australia 2017).

Bullying can have substantial impacts on victims, perpetrators and witnesses, as well as the broader social environment (ReachOut Australia 2017; Rigby & Johnson 2016).

For further details on the types of bullying, see Box 1.

Box 1: Defining bullying

Bullying can be physical, verbal or social.

Physical bullying includes actions that physically harm an individual or their belongings, including stealing from them.

Verbal bullying includes spoken or written words intended to insult or otherwise cause emotional pain to a person.

Social bullying includes actions intended to socially isolate another person or otherwise attack their social standing, for example by sharing personal information with others (Australian Education Authorities 2019; Kids Helpline 2019; Australian Human Rights Commission 2012).

Bullying-like behaviour includes behaviours related to bullying that may not have occurred repeatedly. In some cases, this section includes data on bullying-like behaviour.

Children can be exposed to bullying as victims, perpetrators, bystanders or upstanders. Upstanders, also known as supportive bystanders, attempt to help the victim of bullying in some way by, for example, taking action to stop the bullying or supporting the victim following an incident (Salmivalli 2014; Australian Education Authorities 2019; NSW Department of Education 2019).

Bullying can happen:

- anywhere (for example, at school, home or in the neighbourhood)

- in person or online

- in an obvious or hidden manner (Australian Education Authorities 2019).

Physical, verbal and social bullying can all occur in person.

Cyberbullying, also referred to as online bullying, is a subset of verbal and/or social bullying carried out through technology, such as the internet and mobile devices (Australian Education Authorities 2019; Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2018).

In the absence of a single comprehensive national data source on children who experience bullying, this section draws on multiple data sources to provide some insight into the topic.

While children can be bullied by anyone; for example, peers, siblings or adults, the focus of this section is behaviours carried out by a child’s peers in any setting (for example, at school or online) (Australian Education Authorities 2019; Dantchev & Wolke 2019; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016).

For more information on each data source used throughout this section, see Box 2.

Box 2: Measuring bullying

The data used throughout this section are from data sources that asked children how often they experienced behaviours related to bullying, at least once or repeatedly over a specific period.

Some data sources combine responses to questions about bullying to assign children an overall bullying status, while others report the experience of any bullying-like behaviour.

Physical, verbal and social behaviour that occurs face-to-face or online, are in scope of all data sources presented.

Each data source represents different populations and defines and measures bullying differently. They are not comparable.

Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC)

This study follows the development of 10,000 young people and examines a broad range of areas over their life course. Data are used from children aged 12–13 in 2016. Population estimates from the LSAC represent the population of children aged 0–1 in Australia in 2004. Data are not representative of children who immigrated to Australia.

The LSAC is conducted in partnership between the Department of Social Services, Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

At various points throughout the study, children have been asked about the different types of behaviours they experienced.

Australian Child Wellbeing Project (ACWP)

This survey was led by a team of researchers at Flinders University and the University of New South Wales and administered in 2014 to 5,400 students in Years 4, 6 and 8. It asked children about the types of behaviours they experienced.

Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS)

These studies regularly collect data on bullying as part of internationally comparable educational assessments for children in Years 4 and 8. They are internationally managed by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement and in Australia they are conducted by the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) on behalf of the federal and state and territory governments.

Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing

This is also referred to as the Young Minds Matter survey. It examined the emotional and behavioural development of children and asked participants about their involvement in bullying.

Youth Digital Participation Survey

This Office of the eSafety Commissioner’s 2017 survey asked more than 3,000 young Australians aged 8–17 about their experiences and behaviours related to safety online.

A selection of statistically significant comparisons between population groups have been included throughout.

See Technical notes for details on the specific questions that children were asked in each data source.

How many children are bullied?

The proportion of children who have been bullied or experienced bullying-like behaviours varied depending on the source. This is due to variation in the definition of bullying, and/or the nature and scope of questions asked.

160,000 children aged 12–13 experienced at least 1 bullying-like behaviour within a year

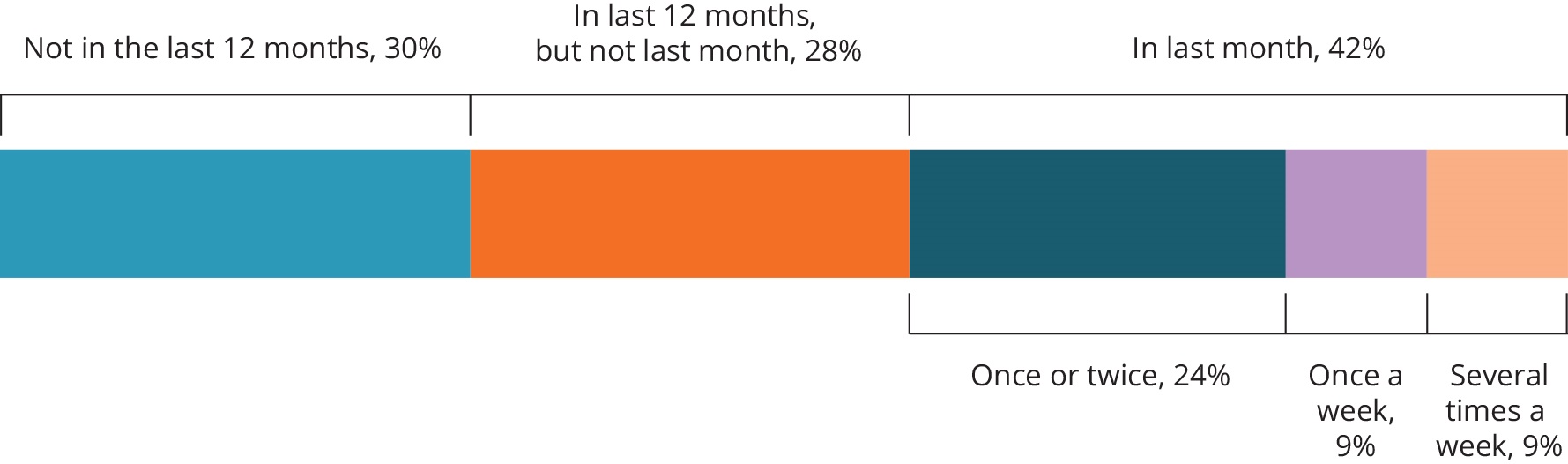

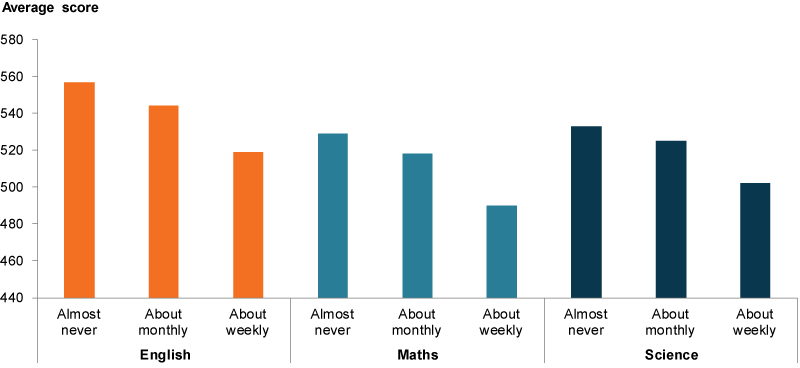

It was estimated using data from LSAC in 2016 that 70% (or 160,000) of children aged 12–13 had experienced at least 1 bullying-like behaviour in the 12 months before the survey (Figure 1). Approximately 60% of the 96,800 children who had experienced bullying-like behaviour, had experiences in the month before the survey.

Of those children who had experienced bullying-like behaviour in the month before the survey, more than two-fifths (43%, or 41,300) had experienced this behaviour about once a week or more frequently (Figure 1) (AIHW analysis of the LSAC).

Figure 1: Proportion of children aged 12–13 who experienced bullying-like behaviour in the 12 months before the survey, 2016

Note: The frequency in the last month refers to the frequency of the main bullying-like behaviour experienced by a child, rather than the frequency of bullying incidents (which may include different behaviours).

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW analysis of the LSAC.

Similar to these findings, the 2014 ACWP found that 60% of students in Years 4, 6 and 8 experienced at least 1 bullying-like behaviour in the same school term the survey was conducted (AIHW analysis of the ACWP).

60% of children experienced 2 or more bullying behaviours

It was estimated using data from LSAC in 2016 that more than half (66%) of the approximately 96,800 children who experienced bullying-like behaviour in the month before the survey experienced 2 or more bullying-like behaviours. Almost 11% experienced 2 or more once a week and about 9% experienced 2 or more several times a week.

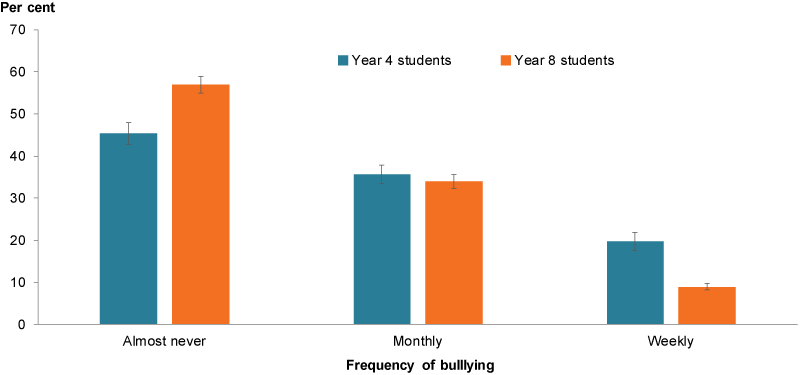

Younger students are bullied more than older students

According to the TIMSS 2015, Year 4 students (average age 10) were more likely to have been bullied than Year 8 students (average age 14). About 56% of Year 4 students and 43% of Year 8 students had been bullied monthly or weekly during the school year (Figure 2) (Thomson, Wernert et al. 2017).

A decrease in bullying with age is consistent with international research findings, with suggested explanations including:

- differences in behaviours included in the definition

- less sensitivity to certain bullying-like behaviours resulting in less self-reporting

- improved social skills (Smith et al. 1999; Eslea & Rees 2001; Ryoo et al. 2015).

Figure 2: Proportion of children bullied during the school year, by frequency of bullying, by year level at school, 2015

Chart: AIHW. Source: Thomson, Wernert et al. 2017.

How common is cyberbullying?

Box 3: What makes cyberbullying different?

Cyberbullying can cause a victim to suffer more acutely and the child who bullies may not be reprimanded for their behaviour. Reasons for this include:

- Invasive nature. Cyberbullying cannot be physically escaped in the same way in-person bullying can. It can happen anywhere and anytime of the day.

- Rapidly and widely spread material. The use of technology means that harmful material, such as images and rumours, can be spread far more quickly than they can in person, and cannot be retrieved or destroyed in the same way physical material can.

- Anonymity and physical distance. Cyberbullies may feel a sense of anonymity as a result of their physical distance from the victim. This can leave a bully feeling more confident in their actions and less likely to stop (Australian Education Authorities 2019; Robinson 2013).

1 in 5 children experienced online bullying-like behaviours in the last month

Data from LSAC in 2016 shows that 17% of all children aged 12–13 experienced online bullying-like behaviour in the month before the survey. Of the 96,800 children aged 12–13 who did so, 10% experienced online bullying-like behaviour only and 32% both online and face-to-face bullying-like behaviours (ABS analysis of the LSAC).

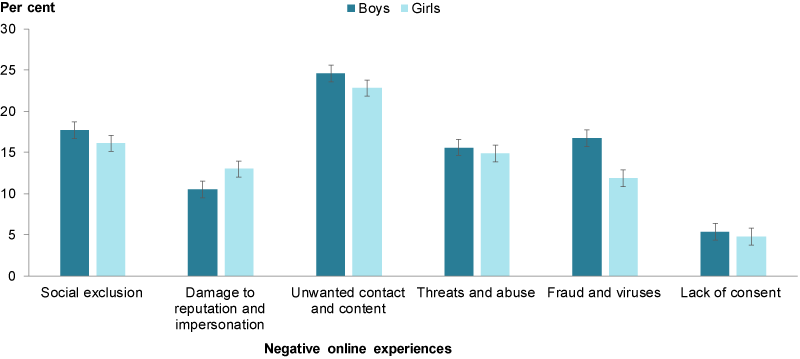

The eSafety Commissioner’s Youth Digital Participation Survey did not specifically ask children about cyberbullying. Rather, it collected information on negative online experiences, which can include some cyberbullying behaviours such as social exclusion or threats and abuse.

Results from the survey showed that unwanted contact and content was the most commonly reported negative online experience for children aged 8–12, with 24% of all children experiencing it. Boys and girls had similar rates for all of the different online negative experiences examined (Figure 3) (Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2018).

Figure 3: Proportion of children aged 8–12 who had negative online experiences, by sex, July 2016 to June 2017

Chart: AIHW. Source: Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2018.

Are some kids bullied more?

While children in any population group can be victims of bullying, those who belong to certain groups or are viewed as being different from their peers tend to be more vulnerable (Australian Education Authorities 2019).

Bullying is more common among children:

- with disability

- from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

- who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse, or children who have intersex variations (Australian Education Authorities 2019; Rigby & Johnson 2016).

Children with a disability are bullied more

The 2014 ACWP found that more children with disability experienced bullying-like behaviours in the same school term the survey was conducted than children without disability (74% compared with 59%, respectively) (AIHW analysis of the ACWP).

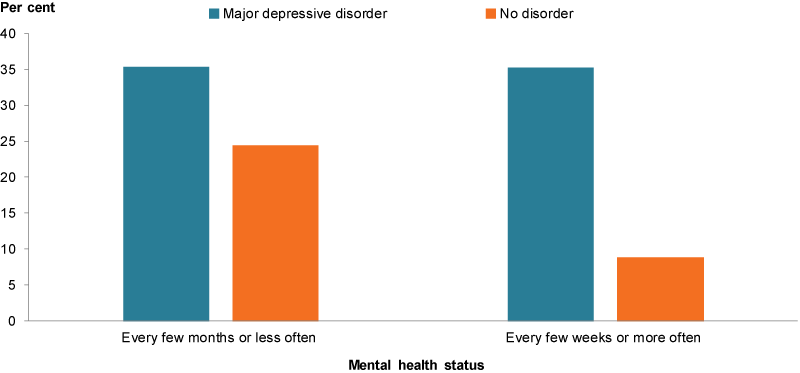

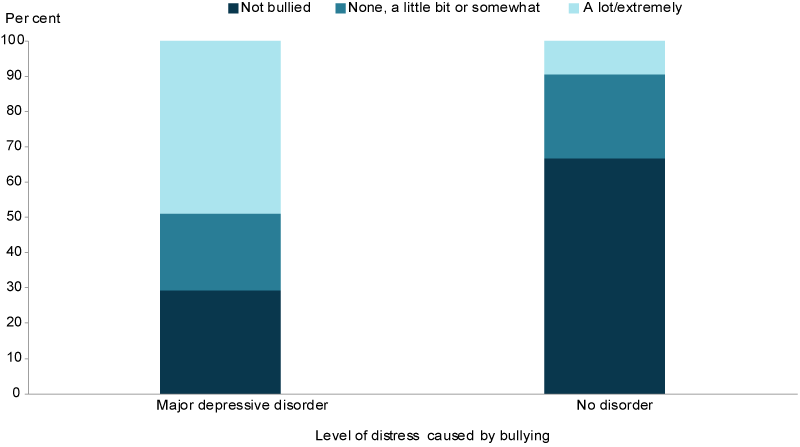

Children with major depressive disorder

In the 2013–14 Young Minds Matter survey, children aged 11–15 with major depressive disorder (based on self-report) were more likely to have experienced frequent bullying in the 12 months before the survey than children with no disorder (Figure 4). In this survey it is not possible to determine if major depressive disorder was caused by, or contributed to, the bullying (Lawrence et al. 2015).

Figure 4: Proportion of children aged 11–15 bullied, by frequency of bullying and mental health status, 2013–14

Chart: AIHW. Source: Lawrence et al. 2015.

Children from socioeconomically disadvantaged schools were bullied more

The PIRLS 2016 found that a higher proportion of Year 4 students from more socioeconomically disadvantaged schools experienced frequent bullying than those attending more affluent schools. About 57% of children from disadvantaged schools had experienced bullying in the 12 months before the survey (23% experienced bullying about weekly) compared with half (50%) of children from affluent schools (15% about weekly) (Thomson, Hillman et al. 2017).

What are the impacts of bullying?

Consequences of bullying

There can be a range of physical, psychological, social and academic consequences for children who are victims, perpetrators, bystanders and upstanders of bullying (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016).

Children who are bullied, as well as those who witness or intervene in bullying, may experience immediate physical or emotional consequences (such as injuries or embarrassment). Children victims of bullying are also:

- more likely to have poor academic performance

- at risk of struggling with transition points throughout life, such as adjusting to secondary school

- more likely to have mental health concerns, such as feelings of anxiety and depression

- at higher risk of suicide (AIFS 2017; Rigby & Johnson 2016).

Bullying and educational attainment

On average, Year 4 students who were bullied achieved lower scores in TIMSS and PIRLS than children who were not, and there was a relationship between the average score achieved by children and the frequency of bullying (Figure 5). A similar pattern was observed among Year 8 students (Thomson, Hillman et al. 2017 & Thomson, Wernert et al. 2017).

Figure 5: Average score on TIMSS 2015 and PIRLS 2016, Year 4 students, by frequency of bullying

Chart: AIHW. Source: Thomson, Hillman et al. 2017 & Thomson, Wernert et al. 2017.

Victims of bullying experience distress

In the Young Minds Matter survey, about 33% of children aged 11–15 who had been bullied said they had experienced a lot of distress caused by bullying in the 12 months before the survey.

The rate is higher among children with major depressive disorder who had been bullied—69% of children with major depressive disorder who had been bullied said they experienced a lot of distress caused by bullying, compared with 29% of children with no disorder (Figure 6) (Lawrence et al. 2015).

Figure 6: Proportion of children aged 11–15, by mental health status, by level of distress caused by bullying, 2013–14

Chart: AIHW. Source: Lawrence et al. 2015.

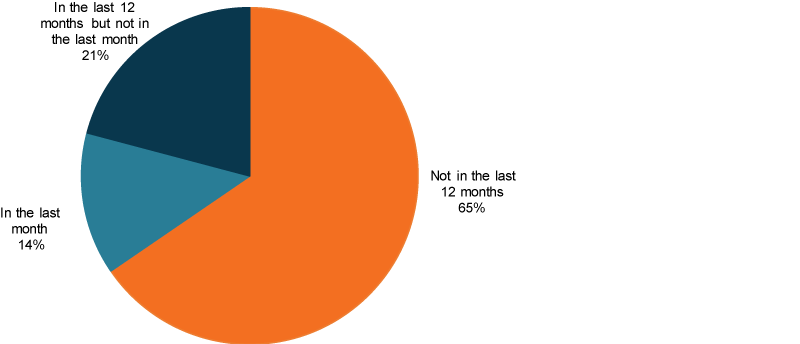

Children who bully others

Data from the LSAC in 2016 showed that about 34% of children aged 12–13 used bullying-like behaviours against another person in the 12 months before the survey, including 14% who used these behaviours in the month before the survey (Figure 7). Of those children who used bullying-like behaviours against another person in the month before the survey, almost half (49%) had used 2 or more types of bullying-like behaviours (AIHW analysis of the LSAC).

Figure 7: Proportion of children aged 12–13 who used bullying-like behaviours against another person in the previous 12 months, 2016

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW analysis of the LSAC.

The ACWP showed that 11% of Year 4 students and 8% of Year 6 students had used bullying-like behaviours against another child in the same school term the survey was conducted (AIHW analysis of the ACWP).

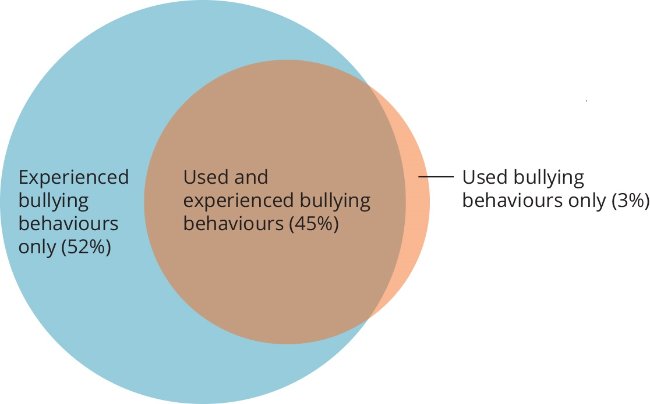

Many children who bully have also been the victim of bullying themselves

Data from the LSAC showed that more children who experience bullying-like behaviours use these behaviours against others than those who do not. About 46% of children aged 12–13 who experienced bullying-like behaviours in the 12 months before the survey had also used these behaviours against another child in the same period, compared with 7.4% of children who did not experience any of these behaviours. Around 94% of children who used bullying-like behaviours against someone else in the 12 months before the survey had also experienced such behaviours in the same period (ABS analysis of the LSAC).

Overall, there was a large amount of overlap between children who experience bullying-like behaviours and those who use these behaviours against others than those who do not (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Children aged 12–13 who have experienced bullying behaviours and children who have used bullying behaviours in the previous 12 months, 2016

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW analysis of the LSAC.

What are the impacts for children who bully?

Research suggests that children who bully other children are:

- more likely to engage in criminal offending and substance abuse

- more likely to have poor educational and employment outcomes

- at higher risk of depression later in life (Australian Education Authorities 2019; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016; Lodge 2014; Vaughn et al. 2010).

Data limitations and development opportunities

There is currently no ongoing comprehensive national data source of children involved in bullying—as victims, perpetrators, bystanders or upstanders—and there are no time-series data available for reporting.

There are a number of opportunities for the development of regular, national data on bullying that could be further explored. These include:

- additional analysis of PIRLS and TIMSS data

- school and/or student level data collected as part of school-based anti-bullying programs (for example, Friendly Schools Plus)

- future eSafety Commissioner data collections

- emerging data sources such as Rumble’s Quest.

Where do I find more information?

For more information on:

- bullying, see: Friendly Schools Plus, Cool Schools and Bullying No Way!

- LSAC, see: Growing UpGrowing Up in Australia in Australia.

AIFS (Australian Institute of Family Studies) 2017. The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2016. Melbourne: AIFS.

Australian Education Authorities 2019. Bullying. No Way! Viewed 8 July 2019.

AHRC (Australian Human Rights Commission) 2012. What is bullying?: violence, harassment and bullying fact sheet. Viewed 8 July 2019.

Dantchev H & Wolke D 2019. Trouble in the nest: antecedents of sibling bullying victimization and perpetration. Developmental Psychology 55(5):1059–1071.

Eslea M & Rees J 2001. At what age are children most likely to be bullied at school? Aggressive Behavior 27(6):419–429.

Kids Helpline 2019. Bullying. Viewed 8 July 2019.

Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven de Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J et al. 2015. The mental health of children and adolescents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Department of Health, Canberra. Viewed 15 July 2019.

Lodge J 2014. Children who bully at school. Australian Institute of Family studies. Child Family Community Australia paper no. 27.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016. Preventing bullying through science, policy, and practice. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NSW Department of Education 2019. Anti-Bullying. NSW Government, Sydney. Viewed 11 July 2019.

Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2018. State of play—youth, kids and digital dangers. Australian Government.

Robinson E 2013. Parental involvement in preventing and responding to cyberbullying. Australian Institute of Family Studies: Family Matters 92:68–76.

ReachOut Australia 2017. Research summary: bullying and young Australians. Sydney: ReachOut Australia

Rigby K & Johnson K 2016. The prevalence and effectiveness of anti-bullying strategies employed in Australian Schools, Adelaide, University of South Australia.

Ryoo JH, Wang C & Swearer SM 2015. Examination of the change in latent statuses in bullying behaviors across time. School Psychology Quarterly 30(1):105–122.

Salmivalli C 2014. Participant roles in bullying: how can peer bystanders be utilized in interventions? Journal of Theory into Practice 53:286–292.

Smith PK, Madsen K & Moody JC 1999. What causes the age decline in reports of being bullied in school? Towards a developmental analysis of risks of being bullied. Educational Research 41(3):267–285.

Thomson S, Wernert N, O’Grady E & Rodrigues S 2017 TIMSS 2015: reporting Australia’s results. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Thomson S, Hillman K, Schmid M Rodrigues S & Fullarton J 2017 Reporting Australia’s results: PIRLS 2016. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Vaughn MG, Fu Q, Bender K, DeLisi M, Beaver KM, Perron BE et al. 2010. Psychiatric correlates of bullying in the United States: findings from a national sample. Psychiatric Quarterly 81(3):183–195.

The Australian Child Wellbeing Project

- The ACWP asked students how often the following bullying-like behaviours happened in the school term:

- Student deliberately ignored or left me out of a group to hurt me

- I was teased in nasty ways

- I had a student tell lies about me behind my back to make other students not like me

- I’ve been made I feel afraid I would get hurt

- I had secrets told about me to others behind my back to hurt me

- A group decided to hurt me by ganging up on me.

- In the ACWP, disability was defined based on students self-reporting that they either: had a disability (such as, hearing difficulties, visual difficulties, using a wheelchair, mental illness) for a long time (more than 6 months); or indicated that they had a disability that made it hard (or stopped them) doing everyday activities, communicating or interacting with others, or doing activities other children their age could do.

The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children

- The LSAC asked study children if they experienced or used specific bullying-like behaviours in the last 12 months and last month. If experienced or used in the last month, they are asked how many times in the last month that it happened. The behaviours include:

- hit or kicked on purpose

- grabbed or shoved on purpose

- threatened to take things

- said mean things or called name

- tried to keep others from being friend

- did not let join in

- used force to steal something

- hurt or tried to hurt with weapon

- stole things to be mean

- forced to do something didn’t want to do.

Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study 2015

- In TIMSS, bullying was measured using a bullying scale that combined students’ responses to questions about how often the following behaviours happened:

- teased or called me names

- left me out of their games or activities

- spread lies about me

- stole something from me

- hit or hurt me (for example, shoved, hit, kicked)

- made me do things I didn’t want to do

- shared embarrassing information about me

- threatened me.

Progress in International Reading Literacy Study 2016

- Bullying was measured through the same methodology as TIMSS.

- Socioeconomic affluence and disadvantage in PIRLS was established by asking school principals to report on the socioeconomic composition of their school by indicating what percentage of students came from economically affluent homes and what percentage came from economically disadvantaged homes.

- The responses to these questions were then used to create 3 categories of school socioeconomic composition:

- More affluent: more than 25 per cent of the student body comes from economically affluent homes and not more than 25 per cent from economically disadvantaged homes

- More disadvantaged: more than 25 per cent of the student body comes from economically disadvantaged homes and not more than 25 per cent from economically affluent homes

- Neither more affluent nor more disadvantaged: all other response combinations.

Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing

- In Young Minds Matter, bullying was measured by asking participants if they had experienced or used bullying face-to-face or online, including:

- teasing

- threatening

- spreading rumours

- physically hurting

- pretending to be someone online with the aim of hurting or threatening another person.

For more information, see Methods.