Summary

Endometriosis is a chronic condition that can be painful, affect fertility and lead to reduced participation in school, work and sporting activities. The condition cost an estimated $7.4 billion in Australia in 2017–18, mostly through reduced quality of life and productivity losses (Ernst & Young 2019). This may be an underestimate, however, due to difficulties in diagnosing endometriosis and underdiagnosis.

What is endometriosis?

Endometriosis occurs when endometrial-like tissue, similar to the tissue normally found lining the uterus, is found in other parts of the body, such as the ovaries, fallopian tubes, peritoneum (the membrane lining the abdominal and pelvic cavities) and the outside of the uterus. These tissues are collectively known as endometriosis and, like the endometrial tissue lining the uterus, they respond to hormones released by the ovaries, causing bleeding. This leads to inflammation and scarring, which can cause painful ‘adhesions’ joining together pelvic organs which are normally separate.

The causes of endometriosis are unclear, but factors that seem to increase the risk of endometriosis include a family history of endometriosis and menstrual cycle factors such as early age at first period, short menstrual cycles, and heavy or long periods (Jean Hailes for Women’s Health 2017b).

Some people with endometriosis experience no symptoms; others may experience pain, heavy menstrual bleeding, bleeding between periods, lethargy and reduced fertility, among other symptoms.

The recommended method of diagnosing endometriosis is via examination of specimens collected during laparoscopy (a type of keyhole surgery) (Dunselman et al. 2014). Based on the extent and location of the endometriosis, the condition is sometimes staged as minimal (stage I), mild (stage II), moderate (stage III) or severe (stage IV) (American Society for Reproductive Medicine 1997). However, the stages may not relate to the severity of symptoms experienced (Vercellini et al. 2007). Other systems for classifying endometriosis also exist (Johnson et al. 2017).

Diagnosis of endometriosis is often delayed, with an average of 7 years between onset of symptoms and diagnosis (Nnoaham et al. 2011). There is no known cure for endometriosis, although it can be managed with medical and/or surgical treatments, including the use of pain-killers, hormonal contraceptives or other hormonal treatments, and the removal of lesions via laparoscopy or laparotomy (abdominal surgery) (Dunselman et al. 2014). In some cases, the uterus may be removed (a hysterectomy); however symptoms can still reoccur.

In most (but not all) cases, the symptoms of endometriosis subside after menopause (Jean Hailes for Women’s Health 2017a).

The National Action Plan for Endometriosis

The National Action Plan for Endometriosis was launched in 2018 with the goal of ‘a tangible improvement in the quality of life for individuals living with endometriosis, including a reduction in the impact and burden of disease at individual and population levels’. The plan has 3 priority areas:

- awareness and education—this involves developing and delivering community awareness campaigns, promoting early education on women’s health in schools, improving access to information for people living with endometriosis, and improving awareness and understanding of endometriosis among health professionals

- clinical management and care—this involves developing clinical guidelines and clinical care standards; promoting early access to intervention, care and treatment options; improving affordability, accessibility and consistency of management; ensuring endometriosis is recognised as a chronic condition by all health practitioners; and narrowing the gap in quality of life between people with endometriosis and their peers

- research—this involves building a collaborative environment for endometriosis research, mining existing data and improving data linkage between sources, and conducting further research to understand causes and impacts and progress towards a cure (Department of Health 2018).

This report provides information about the prevalence of endometriosis in Australia, as well as endometriosis-related hospitalisations. Supplementary tables (tables S1–S12) can be viewed and downloaded on the Data page.

What is endometriosis?

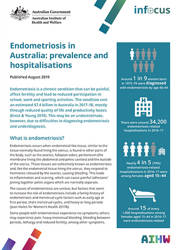

Around 1 in 9 women born in 1973–78 were diagnosed with endometriosis by age 40–44

- How does this study compare with others?

- Another Australian study

- Studies in other countries

There were around 34,200 endometriosis-related hospitalisations in 2016–17

Most endometriosis-related hospitalisations were among females of reproductive age

Rates of endometriosis-related hospitalisations varied by population group

Around 1 in 13 endometriosis-related hospitalisations were self-funded

Most endometriosis-related hospitalisations lasted 2 days or less

Other reproductive conditions were common co-occurring diagnoses

Diagnostic hysteroscopy was undertaken in 2 in 5 endometriosis-related hospitalisations

The rate of endometriosis-related hospitalisations rose slightly over time

What are the data gaps?

What are the opportunities for future work?

End matter: Acknowledgments; Glossary; References