Rheumatoid arthritis

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Rheumatoid arthritis, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Rheumatoid arthritis. Retrieved from https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/rheumatoid-arthritis

MLA

Rheumatoid arthritis. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 14 December 2023, https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/rheumatoid-arthritis

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rheumatoid arthritis [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 19]. Available from: https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/rheumatoid-arthritis

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Rheumatoid arthritis, viewed 19 April 2024, https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/rheumatoid-arthritis

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Page highlights

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic autoimmune condition that causes inflammation, pain, swelling, stiffness and loss of function in joints, commonly in the hands.

How common is rheumatoid arthritis?

An estimated 456,000 (1.9%) people in Australia reported having rheumatoid arthritis in 2017–18.

Impact of rheumatoid arthritis

- People with rheumatoid arthritis had more than double the rates of ‘fair’ to ‘poor’ health (45%), ‘high’ to ‘very high’ psychological distress (29%) and ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ bodily pain (68%), compared with those without the condition.

- Rheumatoid arthritis accounted for 2.0% of total disease burden and 16% of the total burden of disease for all musculoskeletal conditions in 2023.

- In 2020–21, an estimated $966.1 million was spent on the treatment and management of rheumatoid arthritis, representing 0.6% of total health system expenditure and 6.6% of expenditure for all musculoskeletal conditions.

- Rheumatoid arthritis contributed to 1,145 deaths or 3.2 deaths per 100,000 population in 2021, representing 0.7% of all deaths.

Treatment and management of rheumatoid arthritis

In 2021–22, there were 10,000 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (39 hospitalisations per 100,000 population).

Comorbidities of rheumatoid arthritis

Six of 9 comorbidities analysed were significantly more common among people with rheumatoid arthritis compared to those without – the top 3 comorbidities were back problems (36%), mental and behavioural conditions (35%), and heart, stroke and vascular disease (22%).

What is rheumatoid arthritis?

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic autoimmune condition characterised by inflammation of the joints, pain, swelling, stiffness and loss of function in the joints. Rheumatoid arthritis commonly affects the hand joints and both sides of the body at the same time (CDC 2019).

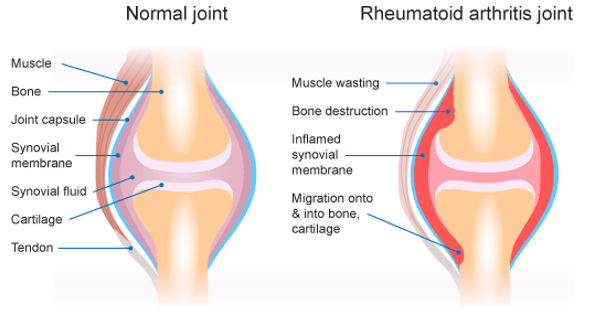

In a healthy joint, the tissue lining the joint (called the synovial membrane or joint synovium) is very thin and produces fluid that lubricates and nourishes joint tissues (RACGP 2009). In rheumatoid arthritis, the immune system attacks the synovial membrane (RACGP 2009). The synovial membrane becomes thick and inflamed, resulting in unwanted tissue growth (Figure 1). As a result, bone erosion and irreversible joint damage can occur, leading to permanent disability (RACGP 2009).

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic disease, affecting the whole body, including the organs. This can lead to problems with the heart, respiratory system, nerves and eyes (CDC 2019). Its cause is not well understood although there is a strong genetic component (CDC 2019). Genetic factors are estimated to contribute 50–60% of the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (Tobón et al. 2010).

Figure 1: Comparison of healthy joint and joint with rheumatoid arthritis

How common is rheumatoid arthritis?

An estimated 456,000 (1.9%) people in Australia reported having rheumatoid arthritis, according to the 2017–18 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Health Survey (NHS) (ABS 2018). This represented 13% of people with any form of arthritis (excluding gout).

For more information about other forms of arthritis, see All arthritis, Osteoarthritis, Gout, and Juvenile arthritis.

Prevalence by age and sex

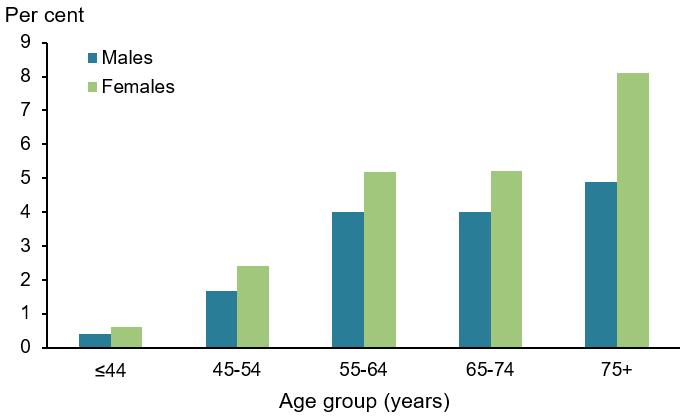

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, rheumatoid arthritis was:

- most common in people aged 75 years and over, although the onset of rheumatoid arthritis most frequently occurred in those aged 35–64 (AIHW 2009; Duarte-Garcia 2019)

- 1.5 times as high in females compared with males (2.3% and 1.5%, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Prevalence of self-reported rheumatoid arthritis, by age and sex, 2017–18

Note: Refers to people who self-reported that they were diagnosed by a doctor or nurse as having rheumatoid arthritis (current and long term) and also people who self-reported having rheumatoid arthritis.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019 (Rheumatoid arthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 1.1).

Impact of rheumatoid arthritis

Many of the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, such as physical limitations, pain, fatigue and mental health issues can impact a person’s ability to engage in daily activities (Radner et al. 2010).

How does rheumatoid arthritis affect quality of life?

Rheumatoid arthritis can affect a person’s ability to participate in work, hobbies and social and daily activities. Combined with the chronic pain associated with rheumatoid arthritis, this can lead to mental health issues including stress, depression and anxiety (Arthritis Australia 2017; Covic et al. 2012).

Rheumatoid arthritis is also a significant cause of physical disability. Functional limitations can become evident soon after the onset of the disease and worsen with time. Joint damage in the wrist is reported as the cause of most severe limitation even in the early stages of rheumatoid arthritis (Koevoets et al. 2013).

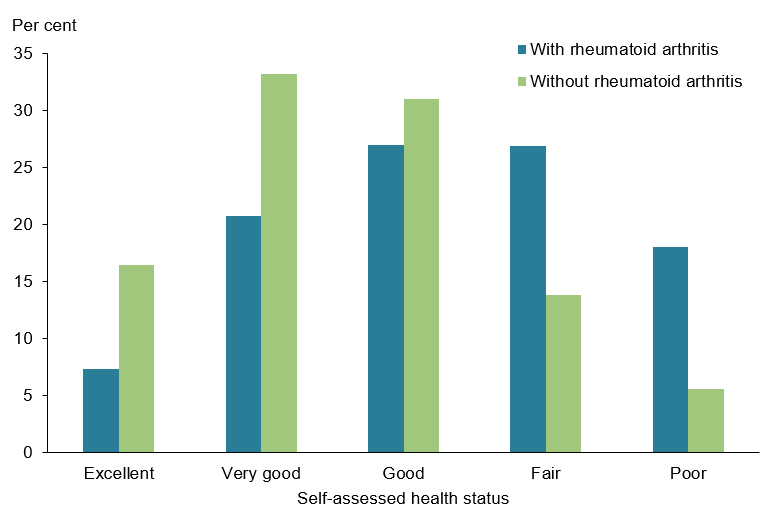

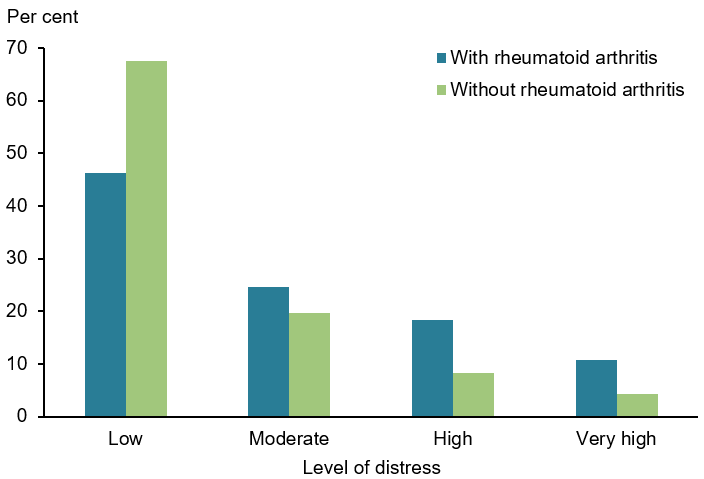

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, after adjusting for age, people aged 45 and over with rheumatoid arthritis were:

- less likely to describe their health as ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’, and 2.3 times as likely to report having ‘fair’ to ‘poor’ health compared with those without rheumatoid arthritis (45% and 19%, respectively) (Figure 3)

- 2.3 times as likely to experience ‘high’ to ‘very high’ levels of psychological distress compared with people without rheumatoid arthritis (29% and 13%, respectively) (Figure 4)

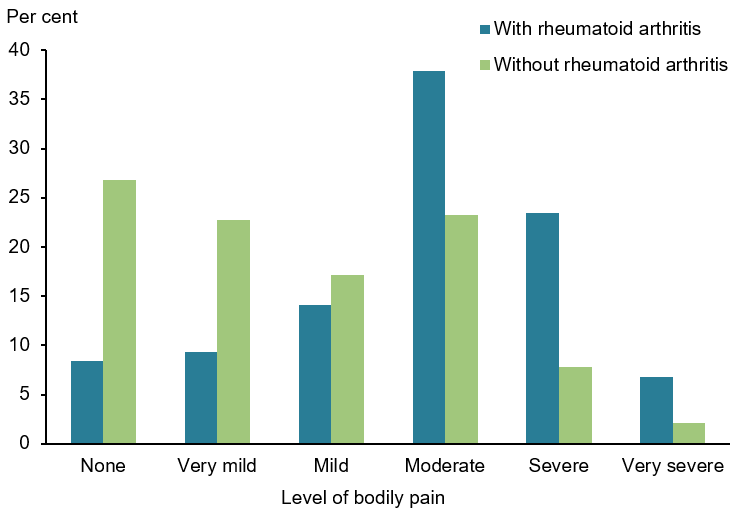

- 2.1 times as likely to experience ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ bodily pain compared with those without rheumatoid arthritis (68% and 33%, respectively) (Figure 5).

Figure 3: Self-assessed health of people aged 45 and over with and without rheumatoid arthritis, 2017–18

Note: Rates are age-standardised to the Australian population as at 30 June 2001.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019 (Rheumatoid arthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 2.1).

Figure 4: Psychological distress experienced by people aged 45 and over with and without rheumatoid arthritis, 2017–18

Note: Rates are age-standardised to the Australian population as at 30 June 2001.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019 (Rheumatoid arthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 2.2).

Figure 5: Pain(a) experienced by people aged 45 and over with and without rheumatoid arthritis, 2017–18

(a) Bodily pain experienced in the 4 weeks prior to interview.

Note: Rates are age-standardised to the Australian population as at 30 June 2001.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019 (Rheumatoid arthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 2.3).

Burden of disease

What is burden of disease?

Burden of disease is measured using the summary metric of disability-adjusted life years (DALY, also known as the total burden). One DALY is one year of healthy life lost to disease and injury. DALY caused by living in poor health (non-fatal burden) are the ‘years lived with disability’ (YLD). DALY caused by premature death (fatal burden) are the ‘years of life lost’ (YLL) and are measured against an ideal life expectancy. DALY allows the impact of premature deaths and living with health impacts from disease or injury to be compared and reported in a consistent manner (AIHW 2022a).

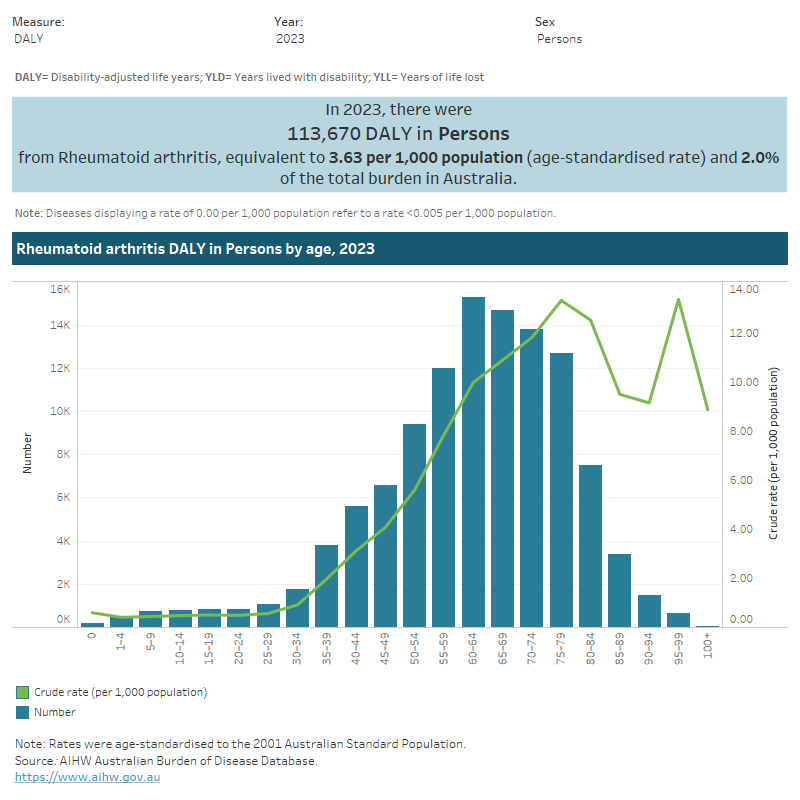

In 2023, rheumatoid arthritis accounted for 2.0% of total disease burden (DALY); 3.6% of non-fatal burden (YLD), and 0.1% of fatal burden (YLL).

Within the musculoskeletal conditions disease group, rheumatoid arthritis accounted for 15.7% of total burden (DALY); 15.7% of non-fatal burden (YLD); and 15.5% of fatal burden (YLL) (AIHW 2023a).

Variation by age and sex

In 2023, the rate of burden from rheumatoid arthritis:

- was 1.6 times as high for females compared with males (5.3 and 3.3 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively)

- averaged 0.6 DALY per 1,000 population for age groups below 30–34, and then rose steeply with age, reaching 13.3 DALY per 1,000 population for 75–79 years (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Burden of disease due to rheumatoid arthritis by sex, age and year

This figure shows the rate of total burden of disease for rheumatoid arthritis was highest for people aged 60–64 in 2023.

Trends over time

Between 2003 and 2023, the age standardised rate of rheumatoid arthritis burden decreased by 36% (from 5.6 to 3.6 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively) – or 2.2% per year on average. Rheumatoid arthritis burden was largely non-fatal in 2023 (97.3% YLD).

For more information, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023.

Variation between population groups

In 2018, the age standardised rate of rheumatoid arthritis burden:

- was highest for people living in Inner regional areas (5.4 DALY per 1,000 population) and lowest for people living in Major cities and Outer regional areas (each 3.4 DALY per 1,000 population)

- was highest for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage) and lowest for people living in the middle socioeconomic areas (5.8 and 2.6 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively) (Figure 7) (AIHW 2021).

For more information, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden.

Figure 7: Burden of disease due to rheumatoid arthritis for remoteness area and socioeconomic group by sex and year

This figure shows that the rate of total burden of disease for rheumatoid arthritis was highest for females living in the lowest socioeconomic areas in 2018.

Health system expenditure

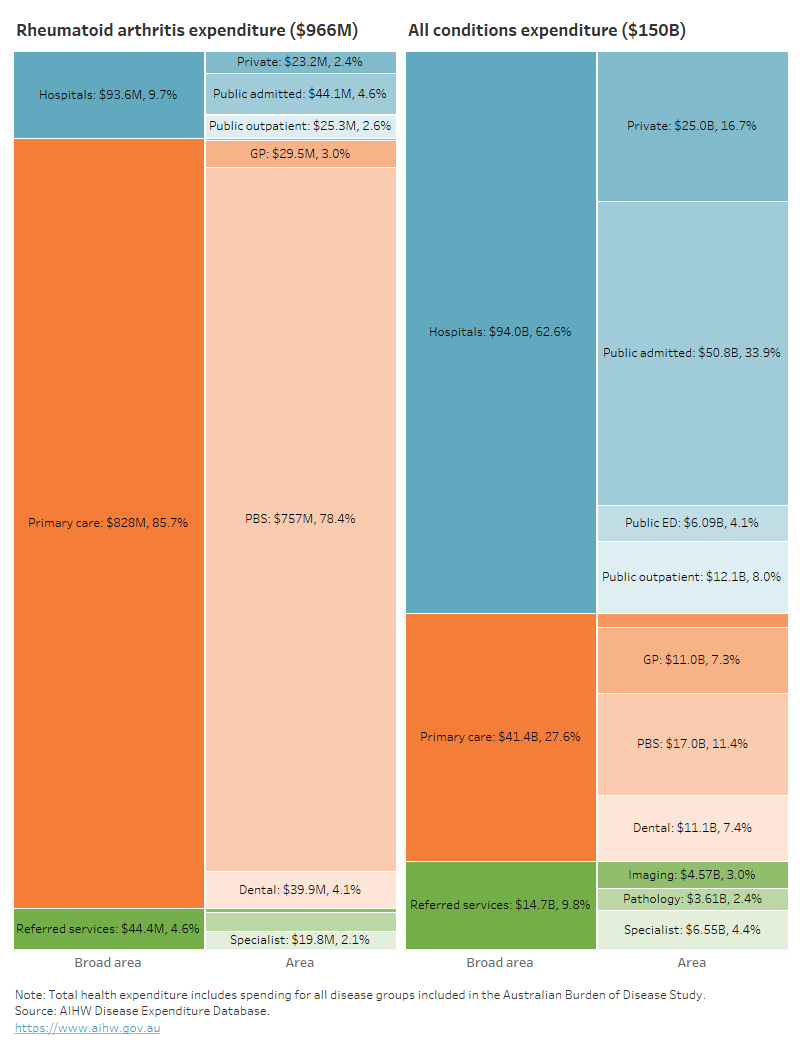

In 2020–21, an estimated $966.1 million of expenditure in the Australian health system was for rheumatoid arthritis, representing 0.6% of total health system expenditure and 6.6% of expenditure for all musculoskeletal conditions (AIHW 2023b).

Where is the money spent?

In 2020–21:

- the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) accounted for 78% of rheumatoid arthritis spending, which was 6.9 times the proportion for all disease groups (11%)

- the dominance of PBS led to primary care accounting for 86% of rheumatoid arthritis spending

- spending for rheumatoid arthritis in all other areas of the health system were proportionately much lower than spending for all disease groups (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Rheumatoid arthritis expenditure attributed to each area of the health system, with comparison to all disease groups, 2020–21

This figure shows that the primary care proportion of rheumatoid arthritis expenditure was $736 million (84%) in 2020-21.

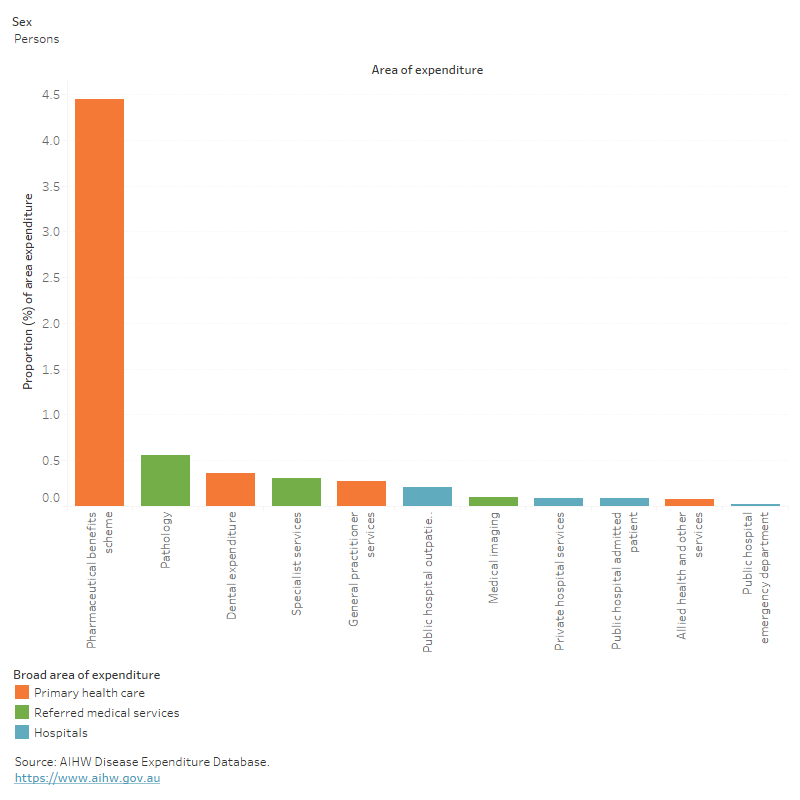

In 2020–21, rheumatoid arthritis accounted for 4.4% ($757 million) of PBS expenditure – ranking third across all diseases/conditions (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Proportion of expenditure attributed to rheumatoid arthritis, for each area of the health system, 2020–21

This figure shows that rheumatoid arthritis accounted for 1.0% of referred medical services expenditure in 2020–21.

Who is the money spent on?

The distribution of health system expenditure on rheumatoid arthritis by age and sex reflects the prevalence distribution, with more spending for older age groups and females.

In 2020–21:

- 77% of rheumatoid arthritis expenditure was for people aged over 45.

- 1.9 times more rheumatoid arthritis expenditure was attributed to females compared with males ($606.3 million and $318 million, respectively), with a remaining $41.8 million (4.3%) unattributed to any sex.

For more information, see Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21.

In 2018–19, it was estimated that rheumatoid arthritis expenditure per case was:

- 16% higher for females compared with males ($2,000 and $1,700 per case, respectively)

- 63% higher than expenditure per case for musculoskeletal conditions as a group ($2,000 and $1,200 per case, respectively) (AIHW 2022b).

For more information, see Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors.

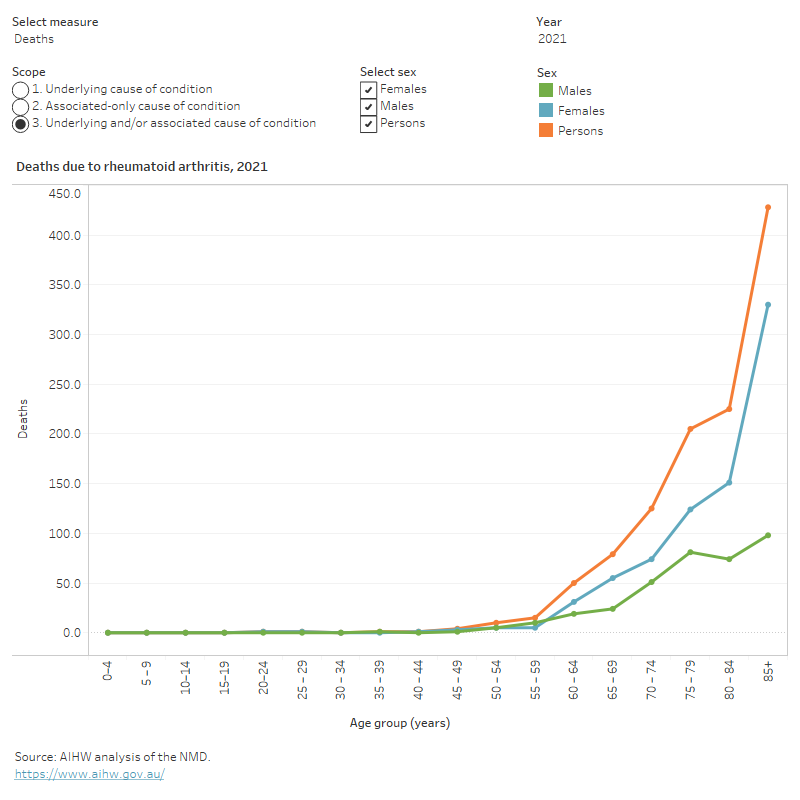

How many deaths were associated with rheumatoid arthritis?

Rheumatoid arthritis was recorded as an underlying and/or associated cause for 1,145 deaths or 3.2 deaths per 100,000 population in Australia in 2021, representing 0.7% of all deaths and 12% of all musculoskeletal deaths.

Rheumatoid arthritis was the underlying cause for 232 deaths (20% of rheumatoid arthritis deaths) and an associated cause only, for 913 deaths (80% of rheumatoid arthritis deaths).

Variation by age and sex

In 2021, rheumatoid arthritis mortality (as the underlying and/or associated cause), in comparison to all deaths, was relatively concentrated among:

- older people (75% of rheumatoid arthritis deaths were among people aged 75 and over, compared with 67% for total deaths)

- females (68% of rheumatoid arthritis deaths were among females, compared with 48% of total deaths) (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Age distribution for rheumatoid arthritis mortality, by sex, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows that in 2021, the rheumatoid arthritis death rate increased from 3.4 per 100,000 population in people aged 60–64 to 80 per 100,000 in those aged 85 and over.

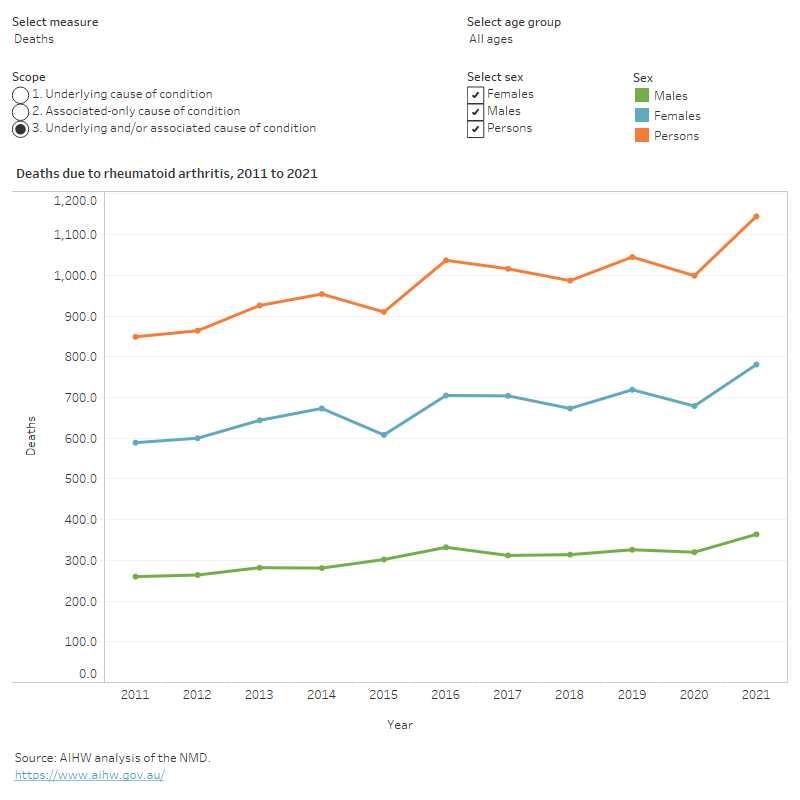

Trends over time

Age standardised mortality rates for rheumatoid arthritis (as the underlying and/or associated cause) between 2011 and 2021:

- trended approximately flat, averaging 3.3 per 100,000 population over the period

- were 1.6 to 1.8 times as high for females compared with males (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Trends over time for rheumatoid arthritis mortality, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows that the female rheumatoid arthritis death rate was lowest in 2015 (5.1 per 100,000 population).

Variation between population groups

In 2021, age standardised mortality rates for rheumatoid arthritis (as the underlying and/or associated cause) were:

- highest for people living in Remote and very remote areas and lowest for people living in Major cities (4.9 and 3.0 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively)

- highest for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest levels of disadvantage) and lowest for people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest levels of disadvantage) (3.7 and 2.3 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively).

For more information on mortality data, see the Chronic musculoskeletal condition mortality data tables 2023.

Treatment and management of rheumatoid arthritis

At present there is no cure for rheumatoid arthritis. The Australian Models of Care for the management of the disease focus on early diagnosis, early management, and coordination of multidisciplinary care needs (Arthritis Australia 2014; Speerin et al. 2014).

Medications are primarily used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, however physical therapy and joint replacement surgery can also be used. Based on the patient’s needs doctors may prescribe medications to manage pain and/or stiffness such as fatty acid supplements, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), COX-2 inhibitors and low dose corticosteroids (RACGP 2009).

Clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of early rheumatoid arthritis includes more information on medications for rheumatoid arthritis (RACGP 2009).

General practitioners and rheumatoid arthritis treatment

GPs have an important role to play in the treatment and management of rheumatoid arthritis. The RACGP recommends GPs complete diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis as soon as possible and refer patients to a rheumatologist if joint swelling persists beyond 6 weeks (Nam et al. 2014); RACGP 2009). Minimising time between diagnosis and referral to a specialist reduces the chances of joint damage occurring and improves long term outcomes for people with rheumatoid arthritis (Bakker et al. 2011: Speerin et al. 2014).

It is worth noting that there is currently no nationally consistent primary health care data collection to monitor provision of care by GPs. For more information, see General practice, allied health and other primary care services.

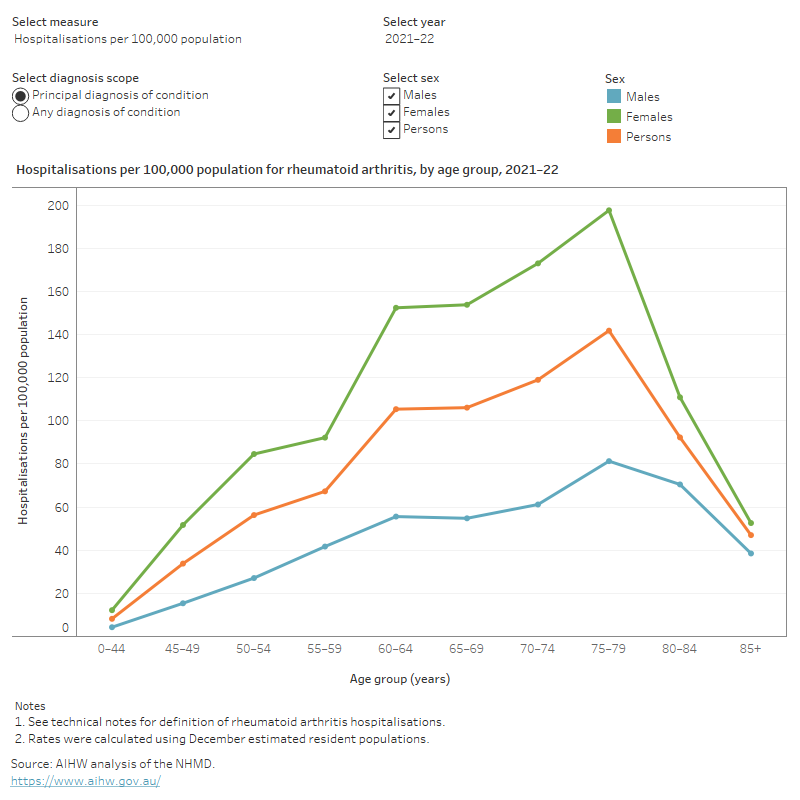

Hospitalisations for rheumatoid arthritis

People with rheumatoid arthritis may require admission to hospital when they experience sudden attacks (flares) of severe pain, swelling and joint pain.

Data from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD) show that in 2021–22, there were 15,600 hospitalisations with a principal or additional diagnosis (any diagnosis) of rheumatoid arthritis, representing 0.1% of all hospitalisations.

The rest of this section discusses hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, unless otherwise stated. However, charts and tables also include statistics for any diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

In 2021–22:

- there were 10,000 hospitalisations for rheumatoid arthritis, representing 0.1% of all hospitalisations in Australia, and 39 hospitalisations per 100,000 population

- rheumatoid arthritis accounted for 20,900 bed days, representing 0.1% of all bed days

- 21% of rheumatoid arthritis hospitalisations were overnight stays, with an average length of 6.3 days (Figure 12).

Variation by age and sex

In 2021–22, rheumatoid arthritis hospitalisation rates were:

- highest for people aged 75–79 years (140 per 100,000 population) (Figure 12)

- 2.7 times as high for females compared with males (57 and 21 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 13).

Figure 12: Age distribution for rheumatoid arthritis hospitalisations, by sex, 2011–12 to 2021–22

This figure shows that the hospitalisation rate for rheumatoid arthritis increased with age up to the 75–79 age group, decreasing thereafter.

Trends over time

From 2011–12 to 2021–22, for rheumatoid arthritis hospitalisations:

- the rate increased from 47 hospitalisations per 100,000 population to 55 per 100,000 population in 2015–16, before decreasing to 39 per 100,000 population in 2021–22

- the proportion of overnight stays decreased from 24% to 21%

- the average length of overnight stays increased from 5.4 to 6.3 days (Figure 13).

It should be noted that the rate of hospitalisations over the past few years may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For more information, see the Chronic musculoskeletal conditions COVID-19 impact section.

Figure 13: Trends over time for rheumatoid arthritis hospitalisations, 2011–12 to 2021–22

This figure shows that between 2011–12 and 2021–22, hospitalisation rates for rheumatoid arthritis were consistently higher for females compared to males.

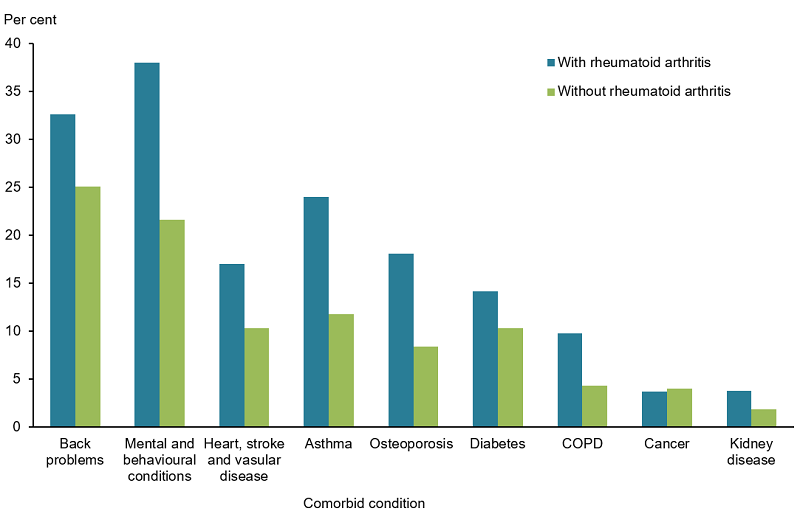

Comorbidities of rheumatoid arthritis

People with rheumatoid arthritis often have other chronic conditions, known as a comorbidity. For this analysis, the following comorbidities were considered:

- arthritis

- asthma

- back problems

- cancer

- diabetes

- heart, stroke and vascular disease

- kidney disease

- mental and behavioural conditions

- osteoporosis or osteopenia.

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, among people aged 45 and over with rheumatoid arthritis:

- 36% also had back problems compared with 25% of people without rheumatoid arthritis

- 35% also had mental and behavioural conditions compared with 22% of people without rheumatoid arthritis

- 22% also had heart, stroke and vascular disease compared with 11% of people without rheumatoid arthritis.

Most chronic diseases are more common in older age groups. The average age of people with rheumatoid arthritis is older than the average age of the general population, therefore people with rheumatoid arthritis are more likely to have age-related comorbidities.

The rates of back problems, mental and behavioural conditions, heart, stroke, and vascular disease, asthma, osteoporosis, and COPD as comorbidities remained significantly higher for people with rheumatoid arthritis compared with those without after adjusting for age (Figure 14). There was no significant difference for diabetes, cancer or kidney disease.

It is important to note that regardless of the differences in age structures, having multiple chronic health problems is often associated with worse health outcomes (Parekh et al. 2011), in addition to a poorer quality of life (McDaid et al. 2013) and more complex clinical management and increased health costs. Rheumatoid arthritis is also associated with increased mortality due to comorbidities and related complications (Lassere et al. 2013).

Figure 14: Prevalence of other chronic conditions in people aged 45 and over, with and without rheumatoid arthritis, 2017–18

Notes:

- Rates are age-standardised to the Australian population as at 30 June 2001.

- These components do not total 100% as one person may have more than one comorbidity.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019 (Rheumatoid arthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 3.1).

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2018) National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–18, ABS website, accessed 24 May 2023.

ABS (2019) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2017–18, AIHW analysis of detailed microdata, accessed 24 May 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2009) A picture of rheumatoid arthritis in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 24 May 2023.

AIHW (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 May 2023.

AIHW (2022a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2022, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023, doi:10.25816/e2v0-gp02.

AIHW (2022b) Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

AIHW (2023a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

Arthritis Australia (2014) Time to move: rheumatoid arthritis, a national strategy to reduce a costly burden, Arthritis Australia website, accessed 19 May 2023.

Arthritis Australia (2017) Emotions, Arthritis Australia website, accessed 4 February 2020.

Bakker M, Jacobs J, Welsing P, Vreugdenhil S, van Booma-Frankfort C, Linn-Rasker S, Ton E, Lafeber G and Bijlsma J (2011) ‘Early clinical response to treatment predicts 5-year outcome in RA patients: follow-up results from the camera study’, Annals of the rheumatic diseases 70 (6):1099–103.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (2019) Rheumatoid Arthritis, CDC website, accessed 16 March 2020.

Covic T, Cummin S, Pallant J, Manolios N, Emery P, Conaghan P and Tennant A (2012) ‘Depression and anxiety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Prevalence rates based on a comparison of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) and the Hospital, Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)’, BMC Psychiatry, 12:6. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-6.

Duarte-Garcia A (2019) Rheumatoid Arthritis, American College of Rheumatology website, accessed 16 March 2020.

Koevoets R, Dirven L, Klarenbeek NB, van Krugten MV, Ronday HK, van der Heijde DMFM, Huizinga TWJ, Kerstens PSJM, Lems WF and Allaart CF (2013) ‘Insights in the relationship of joint space narrowing versus erosive joint damage and physical functioning of patients with RA’, Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 72(6):870–874. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201191.

Lassere MN, Rappo J, Portek IJ, Sturgess A and Edmonds JP (2013) ‘How many life years are lost in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Secular cause-specific and all-cause mortality in rheumatoid arthritis, and their predictors in a long-term Australian cohort study’, Internal Medicine Journal, 43(1): 66–72, doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02727.x.

McDaid O, Hanly MJ, Richardson K, Kee F, Kenny RA and Savva GM (2013) ‘The effect of multiple chronic conditions on self-rated health, disability and quality of life among the older populations of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland: a comparison of two nationally representative cross-sectional surveys’, British Medical Journal Open, 3(6), doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002571.

Nam JL, Ramiro S, Gaujoux-Viala C, Takase K, Leon-Garcia M, Emery P, Gossec L, Landewe R, Smolen JS and Buch MH (2014) ‘Efficacy of biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the 2013 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis’, Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 73 (3):516–528, https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204577.

Parekh AK, Goodman RA, Gordon C and Koh HK (2011) ‘Managing multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework for improving health outcomes and quality of life’, Public Health Reports, 126(4):460–471, doi.org/10.1177/003335491112600403.

RACGP (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners) (2009) Clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of early rheumatoid arthritis, RACGP website, accessed 16 March 2020.

Radner H, Smolen JS and Aletaha D (2010) ‘Comorbidity affects all domains of physical function and quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis’, Rheumatology, 50(2):381-388, doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keq334.

Speerin R, Slater H, Li L, Moore K, Chan M, Dreinhofer K, Ebeling PR, Willcock S and Briggs AM (2014) ‘Moving from evidence to practice: Models of care for the prevention and management of musculoskeletal conditions’, Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 28(3):479–515, doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2014.07.001.

Tobón GJ, Youinou P and Saraux A (2010) ‘The environment, geo-epidemiology, and autoimmune disease: Rheumatoid arthritis’, Journal of Autoimmunity, 35(1):10–14, doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.009.