Residential aged care

Aged care services provided in residential aged care facilities are an important resource for older Australians, including those with dementia. Residential aged care services are particularly important for those in the advanced stages of dementia who need ongoing care, as well as accessible accommodation. People with dementia living in residential aged care have specific care needs that differ to the care needs of others living in residential aged care, such as wandering behaviours, cognition issues and difficulties in undertaking daily activities such as toileting, eating meals, and mobility.

This page uses Aged Care Funding Instrument (ACFI) data to present information on people with dementia who were living in permanent residential aged care in 2021–22, by:

- age and sex, and how age and sex patterns compare to people without dementia living in permanent residential aged care

- state/territory, remoteness and socioeconomic areas

- common co-existing conditions which also impact their care needs

- assistance needs

- time spent in care.

This page also presents how the number and age-standardised rate of people with dementia and people without dementia living in permanent residential aged care has changed between 2017–18 and 2021–22 (skip to this section).

A snapshot of people in permanent residential care on 30 June 2020 showed that ACFI data captures almost all people in permanent residential aged care (over 97% had a current ACFI appraisal) (AIHW 2020a). See Box 10.3 for more information on the ACFI.

Over half of people living in permanent residential aged care have dementia

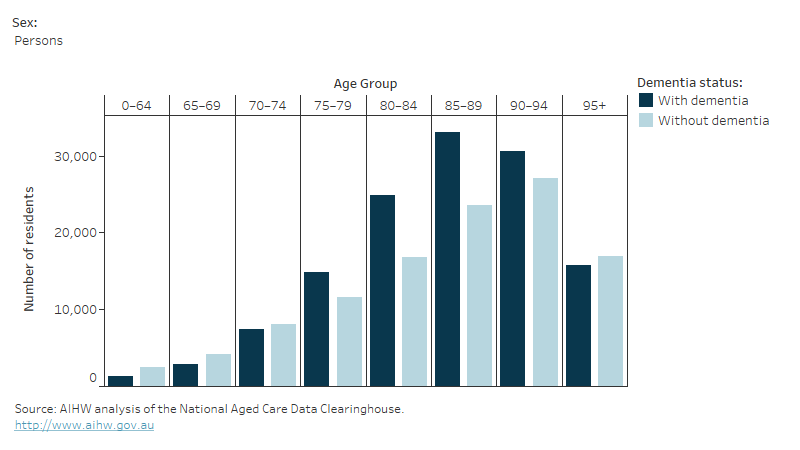

In 2021–22 there were almost 242,000 people living in permanent residential aged care, and 54% of these people had dementia (about 131,000 people). In 2021–22, of those living in permanent residential aged care:

- over half of both women (54% or nearly 84,400) and men (54% or over 46,400) had dementia

- men tended to be younger than women, irrespective of whether or not they had dementia

- both men and women with dementia were similarly aged (84 and 87 on average, respectively) than those without dementia (average of 83 and 87 years)

- 1 in 3 people aged under 65 (35% or 1,300 people) had dementia (known as younger-onset dementia when aged under 65) (Figure 10.7).

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety in its final report made a high priority recommendation that all people under the age of 65 currently living in residential aged care facilities should be moved out of residential aged care and into other, more appropriate care types (Royal Commission, 2021). Through the Younger People in Residential Aged Care Strategy 2020–25, the Australian Government has committed to ensure that apart from exceptional circumstances, no person under the age of 65 lives in residential aged care. See Younger people in residential aged care for the most recent data available to track progress being made towards these targets.

Figure 10.7: People with and without dementia living in permanent residential care in 2021–22: number by age and sex

A bar graph showing the number of people by age, whether or not they had dementia and a drop-down option to change between sexes. For all sexes, with dementia the numbers increase gradually peaking at the age group of 85 to 89, decreasing slightly at age group 90 to 94 and then dropping off. For all sexes those without dementia follows a similar pattern, though less overall and, peaks at age group 90 to 94.

Box 10.3: Residential aged care services and the Aged Care Funding Instrument

Residential aged care is primarily available to older Australians who can no longer live independently in the community, and includes accommodation in a 24-hour staffed facility along with health and nursing services (Department of Health 2020). For approved applicants, places in residential aged care facilities are subsidised by the Australian government, and the Aged Care Funding Instrument (ACFI) was used to allocate government funding to aged care providers based on the day-to-day needs of the people in their care up until the 30th of September 2022. From October 2022 onwards, the Australian National Aged Care Classification funding model (AN-ACC) will be used to determine the amount of funding that aged care providers receive.

The ACFI data did not capture people with dementia who accessed care through some specialised government programs. These include the Multi-Purpose Services Program, which provides integrated health and aged care services to regional and remote communities in areas that can't support both a separate aged care home and hospital, and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flexible Aged Care Program, which provides culturally appropriate aged care to older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, mainly in rural and remote areas.

Although the ACFI was a funding instrument and not a diagnosis or comprehensive service tool, it did provide information on assessed care needs of people in permanent residential aged care at the time of their appraisal; in some instances, not all services received were captured in the ACFI assessment. An ACFI reappraisal could be conducted for various reasons, such as when a person had a significant change in care needs or after 12 months from when their classification had taken effect. Therefore, the ACFI data provided information about people in permanent residential aged care and how their care needs changed over time.

As the care needs and health conditions reported in the ACFI were reported by providers for funding purposes, it is important to remember the ACFI was not a thorough diagnostic or comprehensive service tool, nor is the data collection independent and free from potential conflicts of interest. Furthermore, the ACFI form only allowed for up to 3 medical and 3 mental or behavioural conditions to be recorded, so it did not often provide a comprehensive list of a person’s health conditions.

The proportion of people with dementia living in residential aged care varies across geographic and population groups

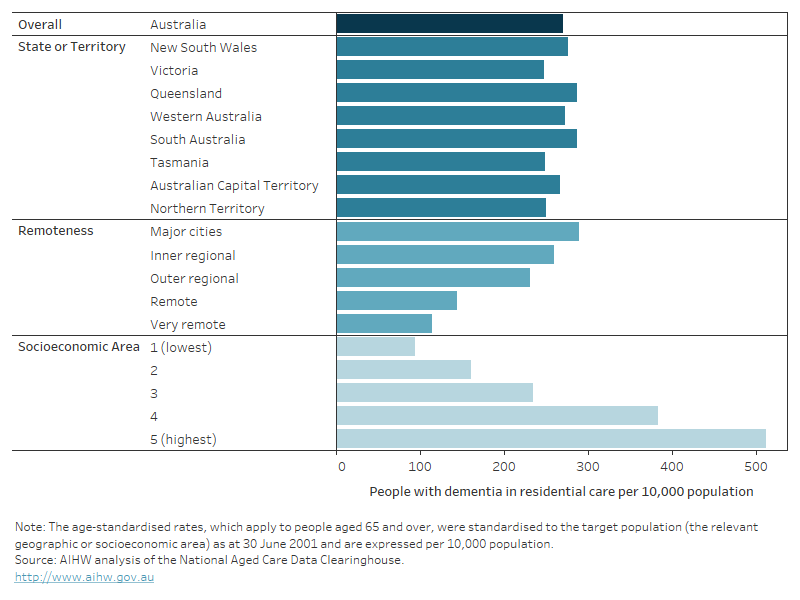

Figure 10.8 shows the rate of people living in permanent residential aged care with dementia in 2021–22, in Australia and by state and territory, remoteness area and socioeconomic area. Rates refer to the number of people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care as a proportion of the target population – that is, those aged 65 and over, in each area of interest. All rates have been age-standardised to adjust for population differences:

- In Australia the rate of people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care was 271 per 10,000 people.

- Across states and territories, there were slight variations in the proportion of people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care, ranging from 248 people per 10,000 people in Victoria to 287 people per 10,000 people in Queensland and South Australia.

- The rate of people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care increased as areas became less remote, from 115 per 10,000 people in Very Remote areas to 289 per 10,000 people in Major Cities.

- Rates of people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care fell as socioeconomic disadvantage decreased – ranging from 94 per 10,000 people in the lowest quintile to 512 per 10,000 people in the highest quintile.

Figure 10.8: People with dementia who were living in permanent residential aged care in 2021–22; age-standardised rate by state/territory, remoteness and socioeconomic area

A panel of bar graphs showing the age-standardised rates of people with dementia by state or territory, remoteness and socioeconomic areas. Between the states and territories, the bars are all similar. Remoteness categories the rate is highest in Major cities and decreases in each category with the lowest rate in very remote locations. Socioeconomic area rates increase from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest).

The provision of aged care varies substantially in more remote areas; other government-subsidised aged care programs not captured in the ACFI, such as the Multi-Purpose Services Program and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flexible Aged Care Program, account for a substantial part of aged care provision in more remote areas. For example, Multi-Purpose Service facilities have been established in small remote communities where previously, community hospitals provided de facto residential aged care.

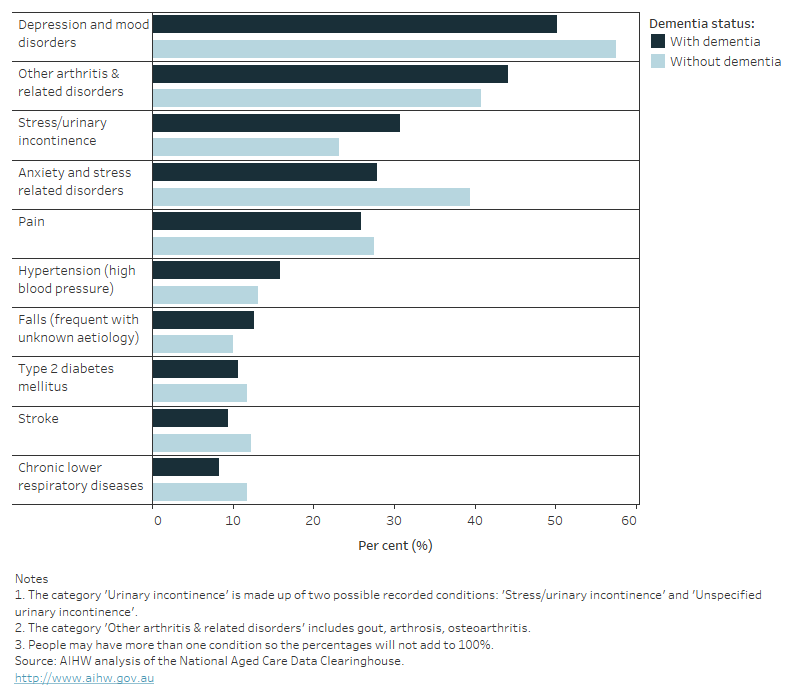

Depression and arthritis are common health conditions among people with dementia

Depression and mood disorders (50%) and a range of arthritic disorders (44%) were the most common health conditions recorded on the ACFI among people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care (Figure 10.9).

Other conditions commonly recorded for people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care were: urinary incontinence (31%), anxiety and stress related disorders (28%), pain (26%), and hypertension (16%).

Compared to those without dementia, people with dementia were more likely to have arthritic disorders (44% compared with 41%), urinary incontinence (31% compared with 23%), hypertension (16% compared with 13%) and frequent falls with unknown aetiology (13% compared with 10%) recorded. Note that the ACFI allows aged care providers to record up to 3 medical conditions and 3 mental or behavioural conditions which impact the residents care needs. Therefore, health condition information from the ACFI will not accurately reflect all co-existing conditions among people living in permanent residential aged care. See Box 10.4 for more information on how health conditions are recorded in the ACFI.

Figure 10.9: Leading 10 health conditions of people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care in 2021–22: percent by dementia status

A bar graph showing the ten most common health conditions of people with and without dementia living in residential aged care.

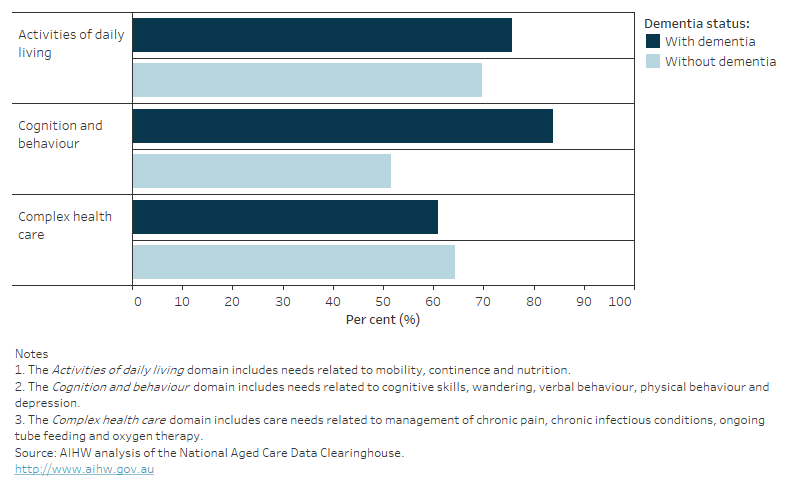

Assistance needs of people with dementia living in residential aged care

As the ACFI is used to allocate funding, it captures the day-to-day care needs that contribute the most to the cost of providing individual care. Care needs are categorised as 'nil', 'low', 'medium', or 'high' based on responses to 12 questions across 3 domains: Activities of daily living, Cognition and behaviour, and Complex health care. People with high care ratings in a domain have more severe needs and require extensive assistance and care in that domain, whereas those with a low care rating have less severe needs. See Box 10.4 for further information on how care needs are assessed for funding purposes using the ACFI tool.

In 2021–22, over half of people in permanent residential aged care with dementia were assessed as needing high levels of care in all ACFI domains. In 2 of the 3 ACFI domains, people with dementia tended to have higher care needs than those without dementia (Figure 10.10):

- over 4 in 5 people with dementia (84%) required high levels of care in the Cognition and behaviour domain (including cognitive skills, wandering, verbal behaviour, physical behaviour and depression) compared to 52% of people without dementia

- over 3 in 4 people with dementia (76%) required high levels of care in the Activities of daily living domain (including mobility, continence and nutrition), compared to 70% of people without dementia

- over 3 in 5 people with dementia (61%) needed high levels of care in the Complex health care domain (including management of chronic pain, chronic infectious conditions, ongoing tube feeding and oxygen therapy), slightly less than people without dementia (64%).

The ACFI also captures cognitive assessment information using the psychogeriatric assessment scale – cognitive impairment scale (PAS – CIS). There are four levels that rank a person's assessed usual cognitive skills: A (no or minimal impairment), B (mild impairment), C (moderate impairment) and D (severe impairment).

In 2021–22, there were an additional 98,700 people without dementia in residential aged care who were deemed to have mild, moderate or severe cognitive impairment, equivalent to 41% of all people living in residential aged care. There could be several reasons for this, including that diagnosed dementia merely wasn't captured in the ACFI as one of the three health conditions most impacting care. However, it may also indicate that there are more people in residential age care in the early stages of dementia who are yet to receive a formal diagnosis.

Overall, 47% of people with dementia living in residential aged care were considered to have severe cognitive impairment, compared to only 8.8% of people without dementia (61,800 and 9,750 people respectively). Additionally, only 10% of people with dementia had no/minimal or mild cognitive impairment, compared with 54% of people without dementia (13,500 and 60,100 people with and without dementia, respectively).

Figure 10.10: People living in permanent residential aged care in 2021–22: percent with the highest care needs in each ACFI domain by dementia status

A bar graph showing the percentage of people with and without dementia who needed help in three ACFI domains: activities of daily living, cognition and behaviour and complex health care.

Box 10.4: How are care needs assessed using the Aged Care Funding Instrument?

The ACFI is a resource allocation tool designed to determine the amount of funding required for the ongoing care needs of people living in residential aged care facilities. The ACFI appraisal is centred on assessing an individual's care needs and consists of 12 care needs based questions, categorised into 3 domains:

- Activities of Daily Living: includes questions regarding nutrition, mobility, personal hygiene, toileting and continence

- Cognition and Behaviour: includes questions regarding cognitive skills, wandering, verbal behaviour, physical behaviour and depression

- Complex Health Care: includes questions regarding medication and complex health care procedures (such as daily blood glucose measurement, management of chronic infectious conditions, oxygen therapy or ongoing tube feeding and palliative care where ongoing care will involve intensive clinical care and/or complex pain management).

Ratings for each domain are used to determine the level of funding required and to assign care. Supporting documentation against each of the ratings, as well as documentation on up to 3 behavioural conditions and up to 3 medical conditions impacting care are also used to determine the funding required.

Low levels of care focus on personal care and support services and some allied health services such as physiotherapy. High levels of care are for those who need almost complete assistance with all tasks. This includes providing 24-hour care, either by or under the supervision of registered nurses, combined with support services, personal care services, and allied health services.

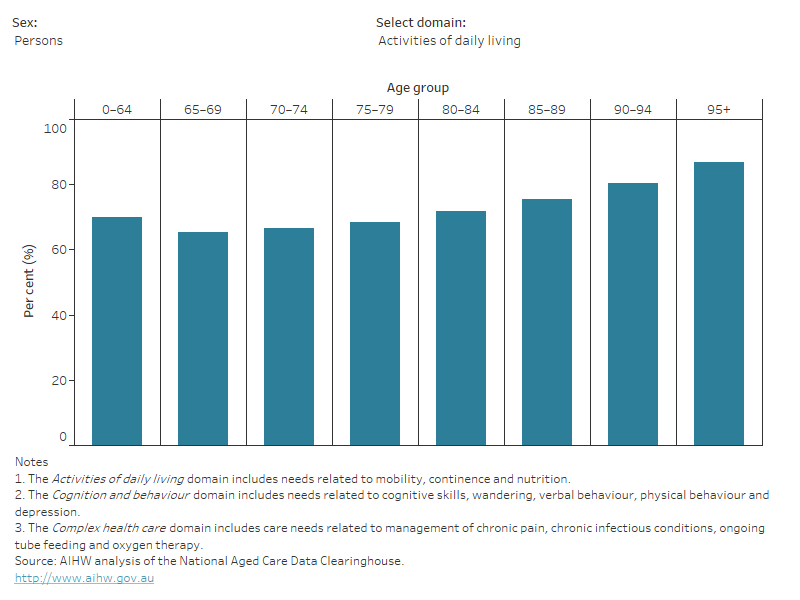

How do the assessed needs of people with dementia living in residential aged care differ by age?

Figure 10.11 shows the proportion of people with dementia in residential aged care who were assessed as having the highest care needs in each of the ACFI domains, by different age groups and sex. For the:

- Activities of daily living domain – the proportion of people requiring high levels of care was greatest among older people with dementia. Proportions were similar by sex, with the exception of the younger age groups, where a higher proportion of women tended to require high levels of care.

- Cognition and behaviour domain – the proportion of people with dementia requiring high levels of care was greatest among people with younger-onset dementia, for both men and women. This could be in part a result of severe behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia being common in dementia types that occur more frequently in younger ages, such as frontotemporal dementia, alcohol-related dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies (Sansoni et al. 2016; Jefferies & Agrawal 2009). Alternatively, this may reflect that younger people are more mobile and have less medical co-morbidities, and so providers may place more emphasis on cognitive needs when completing the ACFI form.

- Complex health care domain – the proportion of people requiring high levels of care increased steadily with age for both men and women.

Refer to Overview of dementia support services and initiatives for information on behavioural supports services for people with dementia.

Figure 10.11: People with dementia living in permanent residential aged care in 2021–22: percent with the highest care needs in each ACFI domain by sex and age

A bar graph showing the percentage of people with dementia living who were assessed as having the highest care needs in each of the three ACFI domains, by age group and sex. For all sexes the percentage of residents requiring a high level of care in activities of daily living and complex health care increases with increasing age. Percentage of residents with high level of care in cognition and behaviour decreases slightly with age, though mostly remains stable at 84%.

How do the assessed care needs vary by geographic and population areas?

The assessed needs of people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care in 2021–22 varied by geographic and population groups (refer to Table S10.19):

- across all 3 ACFI domains, the largest variations were seen by remoteness area with the proportion of people with dementia requiring high levels of care decreasing with increasing remoteness

- Victoria had the highest proportion of people with dementia who required high levels of care in the Activities of daily living domain, whilst the Northern Territory had the highest proportion of people with dementia who required high levels of care in the Cognition and behaviour domain, and Victoria and South Australia had the highest proportion of people with dementia who required high levels of care in the Complex health care domain

- the Australian Capital Territory had the lowest proportion of people with dementia who required high levels of care in the Activities of daily living domain, South Australia had the lowest proportion of people with dementia who required high levels of care in the Cognition and behaviour domain, and Western Australia had the lowest proportion of people with dementia who required high levels of care in the Complex health care domain

- the proportion of people with dementia who required high levels of care were slightly lower for those in more disadvantaged areas, across all domains.

Note, these data should be interpreted with caution due to the smaller number of people living in permanent residential aged care in more remote areas, and because other government subsidised residential services are more commonly available in remote areas (like the Multi-Purpose Services Program and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flexible Aged Care Program) but are not captured in the ACFI data. Differences by remoteness area could also be due to some remote areas not having the facilities and resources to care for people with higher care needs. As a result, some people with dementia may be required to move to less remote locations to access appropriate care.

Case study: Chronic pain management and palliative care for people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (the 'Royal Commission') has exposed systemic issues related to inappropriate and substandard care in Australia's residential aged care setting and the negative impact this has on the mental and physical wellbeing of people in care. The Royal Commission has also documented the increasingly complex care needs of people living in residential aged care and that unmet needs (like untreated pain) are related to changed behaviours for people with dementia (Royal Commission 2019).

In this context, the needs for pain management and palliative care for people with dementia as recorded in the ACFI, is an important component of the services provided in residential care. As part of the Complex health care domain, the ACFI records information on ongoing pain management and palliative care services provided.

In 2021–22, among people with dementia living in permanent residential aged care, 83% required complex pain management at least weekly, and 57% required at least 4 long (80 minutes or longer) pain management sessions every week.

The ACFI also records whether a person is assessed as needing a palliative care program (involving end-of-life care) where ongoing care requires intensive clinical nursing and/ or complex pain management in the residential care setting. A small number of people with dementia in care in 2021–22 were assessed as needing palliative care (about 2,300 or 1.8%) at the time their ACFI appraisal was completed, which was slightly less than for the proportion of people without dementia (about 2,500 or 2.3%). These percentages likely underestimate the proportion of people needing palliative care as they only capture people assessed as needing palliative care at the time the ACFI assessment was conducted. In addition, because some people may receive end of life care in other settings such as hospitals, these care needs are not captured in ACFI data.

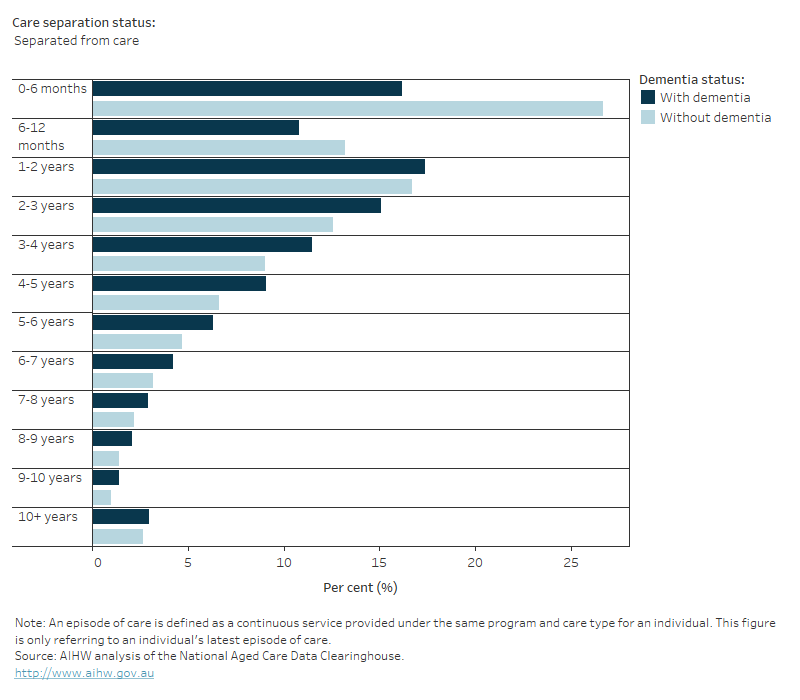

How long are people with dementia living in residential care?

When a person enters residential aged care, and how long they remain in care, is impacted by various factors like: a person's preferred living arrangements, wait times for residential places from point of assessed eligibility, the complexity of care needs and existing comorbidities, the availability of informal carer and alternative care settings; and the quality of care provided in residential care. The Government has been placing a strong focus on giving older Australians the support they need to remain living in the community as long as possible, and recent research shows the timely availability of high-level home care packages plays a big role in whether people with dementia can delay entry to residential care (Welberry et al. 2020).

A person can have more than one 'episode of care' in a residential aged care facility in a given year if, for example, they moved from one facility to another. A separation from an 'episode of care' is most commonly due to: death, prolonged admission to hospital, movement to another residential aged care facility, or returning to the community. Of people with dementia who were receiving care in 2021–22, 1 in 3 people had separated from their latest episode of care that year. Most of these separations were due to death (96% of people with dementia and 93% of people without dementia who separated from their latest episode of care in 2021–22) (Table S10.22).

For people living in permanent residential aged care who did not separate from their latest episode of care during 2021–22, those with and without dementia had spent roughly the same length of time in care (median stay of 2.2 and 2.0 years, respectively). In contrast, for people who separated from their latest episode of care, there were larger differences by dementia status – people with dementia had spent a median of 2.3 years in care compared to 1.5 years for those without dementia (Figure 10.12).

These results may suggest that people without dementia may enter care closer to death as they may be able to live longer in the community, or perhaps that people with dementia separate to use other services less frequently (and may be more likely to die in residential aged care). Recent studies have found that towards the end of life, people with dementia tend to use hospital care at lower levels compared to people without dementia, and that dementia is a common cause of death for people who died in permanent residential aged care (AIHW 2020b; Dobson et al. 2020; AIHW 2021).

Figure 10.12: Time spent in care for people living in permanent residential aged care in 2021–22: percent by dementia status and whether the person separated from care or remained in care

A bar graph showing how long people with and without dementia had spent in permanent residential aged care, by whether they separated from care or not. Those that did separate from care, and those that did not separate had a similar pattern of length of stay.

Trends in the use of residential care

The number of people living in permanent residential aged care was steadily increasing between 2017 and 2020 (from 241,000 people in 2017–18 to 244,000 people in 2019–20). Since then, there has been a small but steady decline in the number of people living in permanent residential aged care.

The Australian Government manages the supply of aged care places, aiming to increase the number of places available in government subsidised permanent residential care relative to the growth of Australia's older population (AIHW 2021). The number of men and women in permanent residential aged care between 2017–18 and 2021–22 differed slightly by dementia status – the number increased by 2.2% for men with dementia but decreased by 1.7% for men without dementia. For women, the number decreased by 2.3% and 2.7% for those with and without dementia, respectively. The proportion of people with dementia remained relatively stable at around 54–55%. The proportion of people in permanent residential aged care with dementia remained relatively stable between 2017–18 and 2021–22 at around 54–55%. (see Table S10.24).

Between 2017–18 and 2021–22 the crude and age-standardised rate of people living in permanent residential aged care aged 65 and over decreased overall, irrespective of if they had dementia or not, but the decrease was slightly greater among those with dementia. This might be linked to the preference of many older people to remain living in the community as long as possible, and correspondingly, an increased government focus on supporting alternatives to residential aged care (Royal Commission 2020).

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2020a) People using aged care, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 8 July 2021.

AIHW (2020b) Patterns of health service use by people with dementia in their last year of life: New South Wales and Victoria, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 June 2023.

AIHW (2021) Providers, services and places in aged care, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 8 May 2021.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) COVID-19 outbreaks in Australian residential aged care facilities – 14 April 2023, Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government, accessed 17 June 2023.

Dobson AJ, Waller MJ, Hockey R, Dolja-Gore X, Forder PM and Byles JE (2020) 'Impact of Dementia on Health Service Use in the Last 2 Years of Life for Women with Other Chronic Conditions', Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(11):1651-1657, doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.02.018.

Royal Commission (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety) (2021) Final report: Care, dignity and respect, Royal Commission, Australian Government, accessed 26 June 2023.

Royal Commission (2020) Research Paper 4: What Australians Think of Ageing and Aged Care, Royal Commission, Australian Government, accessed 10 October 2020.

Welberry HJ, Brodaty H, Hsu B, Barbieri S and Jorm LR (2020) 'Impact of Prior Home Care on Length of Stay in Residential Care for Australians with Dementia', Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(6):843-850, doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.023.