Summary

On this page:

The summary of findings is below. To read the full report, please download the publication as a PDF (or in another format). All data and supplementary tables can be found under the Data tab. A Technical Document, available under Related material, provides more detail on the analysis methods used for the report.

Younger onset dementia in Australia

Dementia is a major health issue in Australia. It is not a single disease – there are many types of dementia with symptoms in common, and these are caused by a range of conditions affecting brain function. Dementia is most common among older people; ‘younger onset dementia’ refers to dementia that begins before the age of 65. While exact numbers are not known, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) estimated that around 27,800 Australians had younger onset dementia in 2021, and this number is projected to increase to 39,000 by 2050 (AIHW 2021b).

The needs and care requirements of people with younger onset dementia, their families and informal carers are often different from those of older people. A diagnosis may occur at an age when the demands of family and work are at a peak, placing a severe strain on family and carer dynamics and finances. People with younger onset dementia often retain good physical health, which can affect the appropriateness of dementia services that are targeted at older people. In the absence of age-appropriate options, people with younger onset dementia may need to enter residential aged care (AIHW 2021b). Recent policy changes seek to provide better alternatives for supported accommodation (Department of Health 2020; DSS 2020).

Better evidence using linked data

Most dementia research focuses on older people. There is a need for better evidence to inform policy and service responses to support younger people with dementia, including work responding to the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (the Royal Commission).

Linked data provide a new opportunity to present a more comprehensive picture of people with younger onset dementia. This report presents findings from 2 new multi-source enduring linked data sets, each of which focuses on different information:

- The Multi-Agency Data Integration Project (MADIP) includes information on Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) medicines, sociodemographic characteristics in the 2016 Census, and income support payments received through Centrelink.

- The National Integrated Health Services Information Analysis Asset (NIHSI AA) contains information on PBS medicines, health services, residential aged care (RAC) and mortality.

PBS claims data were used to create a younger onset dementia study cohort in both linked data sets, allowing parallel analysis of the same group of people over a 5- to 6-year period between 2011–2012 and 2017. The information in the 2 linked data sets was used to describe the social and financial circumstances of people with younger onset dementia, their general practitioner (GP) and specialist attendances, medicines dispensed, emergency department (ED) visits and hospital stays, use of respite and permanent RAC services, and causes of death.

Box 1: The study cohort of people with younger onset dementia

Rather than looking at all people with younger onset dementia, this study focused on people at a relatively early stage of dementia – as identified by the dispensing of dementia-specific medications. This allowed analysis of characteristics and service use over time from a similar starting point.

More specifically, in this report, ‘people with younger onset dementia’ refers to a cohort of about 5,400 Australians aged 30–69. This is a subset of the total population with younger onset dementia, including only those who were relatively early in their disease progression and who were dispensed dementia-specific medications through the PBS in 2011–2012.

- The inclusion of people aged 65–69 made an allowance for delays between the onset of disease, diagnosis and treatment, and for people who started taking the medication before the start of the study period while aged under 65.

- There were slightly more women in the cohort (52%) than men (48%).

- There were some small differences in the number of people in the MADIP and NIHSI AA cohorts, but on average there were about 2,500 people aged 30–64 and about 2,900 people aged 65–69.

Not all types of dementia are represented in the study cohort

Dementia-specific medications (anticholinesterases) are targeted at people with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Other types of dementia that are common in younger people (such as dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal dementia and secondary dementias) are not usually treated with these medicines and are therefore under-represented in the cohort, and the specific needs of these groups (such as greater problems with language or mobility) are not fully identified. In addition, not all people with Alzheimer’s disease are dispensed dementia-specific medication. As a result, generalisation of these results to all people with younger onset dementia should be done with caution.

Overview of outcomes for people with younger onset dementia

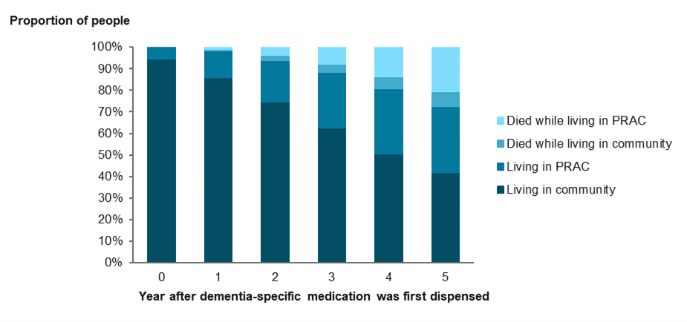

Most people (95%) in the younger onset dementia cohort were living in the community when dementia-specific medication was first dispensed in 2011–2012, with 5% living in permanent residential aged care (PRAC) (Figure 1). By the fifth year after medication was first dispensed, 42% of people were still living in the community and 31% were living in PRAC. About one-quarter (27%) of the cohort had died within 5 years, predominantly those who had lived in PRAC.

Figure 1: Outcomes for people with younger onset dementia (ages 30–69), by year since dementia-specific medication was first dispensed in 2011–2012

Source: AIHW analysis of NIHSI AA v0.5, Table S5.2.

Most people with younger onset dementia live in major cities

In 2016 (4 to 5 years after the start of the study period), 72% of the study cohort lived in Major cities (ABS 2022), but unlike the pattern for all Australians, this proportion did not decrease in older ages. The relationship between place of residence and dementia is complex, and further work is required to tease out issues relating to the prevalence of dementia and adequate access to services.

Cultural and linguistic diversity among people with younger onset dementia

Australians from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds may face numerous barriers in accessing dementia services, including language barriers. According to the 2016 Census, 21% of people with younger onset dementia were born in a non-English speaking country, most commonly Southern and Eastern European countries. This reflected the pattern for all Australians of a similar age. One-quarter of the study cohort (26%) spoke a language other than English at home, most commonly Italian, Greek or Chinese languages.

A relatively high proportion of the study cohort spoke English not well or not at all (9.0%), compared with 4.4% of all Australians of a similar age. This may be partly related to the progression of dementia, but also highlights the need for culturally appropriate services in the community, in supported accommodation, and for family and carers.

A high proportion of people with younger onset dementia received income support through Centrelink

People who develop dementia while still working may face a sudden or early retirement, resulting in significant social, emotional and financial impacts on the person and their family. In the 2016 Census (4 to 5 years after the first dispensed dementia-specific medication), 21% of the study cohort who were still aged under 65 reported that they were employed, and 72% were unemployed or not in the labour force. When only people aged 60–64 were analysed, people with younger onset dementia were less likely to be employed (7.4%) than all Australians of the same age (46%).

People aged 60–64 with younger onset dementia were also more likely (53%) to report lower income categories (personal annual income between $1 and $25,999) than all Australians of the same age (30%). This may partly reflect the high proportion of the study cohort receiving income support through Centrelink. Four years after their first dispensed dementia-specific medication, 71% of those in the 30–64 age group who were still alive received a Centrelink payment: 36% received the Disability Support Pension and 29% received the Age Pension.

Many people with younger onset dementia needed help with day-to-day activities while living at home

In the 2016 Census, 3 in 5 people (61%) of the study cohort who were living at home needed help with at least one of the 3 core activity areas of self-care, mobility and/or communication, compared with 7.4% of all Australians of a similar age. Nearly half of those living at home who were not married or in a de-facto relationship were living by themselves. The available data did not reveal whether people were receiving the help that they needed. Children whose parents have younger onset dementia face particular challenges, including reversal of the parent-child caring role: 18% of people with younger onset dementia aged under 65 in 2016 had dependent children.

Comparing the health service use of people who entered PRAC with those who did not

One of the aims of this study was to explore any potential differences in health service use between people with younger onset dementia who went on to enter PRAC, and those who remained in the community for the duration of the study period.

People who went on to enter PRAC had fewer GP and specialist attendances on average than people who remained in the community

While living in the community, in the first year after dementia-specific medication was dispensed, people in the 30–64 age group who went on to enter PRAC had 8.7 GP and 2.9 specialist attendances, compared with 12 GP and 3.8 specialist attendances by those who remained in the community. This may point to differences in access to services that enable people to stay at home, however, without more detailed data on the reasons for GP and specialist attendances (dementia-related or otherwise), it is difficult to tease out potential areas of inequity. The most common types of specialists seen by both groups were consultant physicians in psychiatry, neurology and geriatric medicine.

People who went on to enter PRAC were more likely to continue being dispensed dementia-specific medication for at least 6 years (76% of those in the 30–64 age group) than those who remained in the community (63%), and were also more likely to start being dispensed memantine, a drug used for later stages of dementia.

People who went on to enter PRAC were 4 times as likely to have an overnight hospital stay for dementia as people who remained in the community

Each year while living in the community, about one-quarter of people with younger onset dementia had an ED presentation, and one-quarter had a hospital stay. Neurological system illness was the most common reason for ED presentations, and about half of ED presentations ended with the person being admitted to hospital. For those who went on to enter PRAC, about 1 in 5 overnight hospital stays (21%) ended with the patient moving to a residential aged care facility that was not their usual place of residence.

Respite RAC was used by a third (34%) of people who went on to enter PRAC

In contrast, only 15% of people who remained in the community had a respite RAC stay. One-quarter (26%) of people were aged under 65 when they first used respite RAC and men were more likely to use respite RAC than women.

One-quarter of people with younger onset dementia were aged under 65 when they first entered PRAC

More than half (58%) of the cohort had a PRAC stay by the end of the 5- to 6-year study period. About 1 in 10 people (11%) had their first PRAC stay within one year of the first dispensed dementia-specific medication, and nearly half (49%, cumulative) within 3 years. Younger people (aged under 65) whose PRAC stay ended in death had a median length of stay of 2 years, compared with 3.4 years for PRAC stays that were ongoing at the end of the study period.

Health conditions and care needs of people in PRAC

The Aged Care Funding Instrument (ACFI) is used to allocate government funding to aged care providers based on the day-to-day needs of the people in their care. At their first ACFI assessment, 83% of people with younger onset dementia were assessed as needing high levels of care in at least one of 3 domains, most commonly in the Cognition and behaviour domain. In addition to dementia, depression and incontinence were commonly recorded health conditions.

Health service use changed after entry to PRAC

Entry to PRAC is often accompanied by a change in health service use: in the 12 months after entry to PRAC, GP attendances for people with younger onset dementia more than doubled, while specialist attendances halved. These patterns were similar to those seen for people with dementia of all ages (AIHW 2021b) and for the residential aged care population overall (AIHW 2020a).

Injuries were the most common reason for hospitalisation after entry to PRAC, accounting for 21% of ED presentations, 23% of same-day and 16% of overnight hospital stays.

The dispensing of antipsychotic medicines increased from 44% to 63% of people in the 6 months after entry to PRAC

Changes in medication often reflect the events that have led to a move to PRAC, such as changed behaviours. Non-pharmacological interventions are recommended as the first approach, but medical professionals may also prescribe antipsychotic medicines to help manage these symptoms. Inappropriate prescribing of antipsychotic medicines, sometimes as a form of chemical restraint to control behaviour, and the prescription of medicines that have negative interactions with each other, were key issues raised in the Royal Commission (2021).

In the 6 months before and after entry to PRAC, the proportion of people with younger onset dementia with polypharmacy (where 5 or more distinct medicines are dispensed) increased from 40% to 61%.

During this time, there was also an increase in the proportion of people dispensed drugs that act on the central nervous system (other than dementia-specific medications). For example, the dispensing of antipsychotic medicines increased from 44% to 63% of people. Over a quarter (28%) of people were new users of antipsychotics, with a median of 29 days between entry to PRAC and new dispensing.

About 2 in 5 people (42%) in the cohort had died by the end of the study period

Dementia is a degenerative condition that leads to reduced life expectancy. Most (78%) of those in the younger onset dementia cohort who died had lived in PRAC. About three-quarters of people (78%) had dementia recorded as an underlying cause of death or associated cause of death, but 22% did not have dementia recorded on their death certificate. Parkinson’s disease was the most common underlying cause of death recorded for these people. The inconsistent recording of dementia on death records remains a significant issue in dementia data in Australia and internationally.

Summary

1. Introduction

- Overview of younger onset dementia in Australia

- The importance of better information about people with younger onset dementia 2

2. Methods

- Data sources

- Study population

- Overview of analysis

- Comparison between the MADIP and NIHSI AA cohorts

- People with evidence of younger onset dementia in the NIHSI AA

- Report structure

3. Characteristics of people with younger onset dementia

- Age and sex profile of the MADIP study cohort

- Census data

- Cultural and linguistic diversity

- Socioeconomic status

- Remoteness areas

- Need for assistance with day-to-day activities

- Families and household composition

4. Financial impact of younger onset dementia

- Employment status and income

- Income support recipients

5. The younger onset dementia cohort in the NIHSI AA

- Age and sex profile of the study cohort

- Overview of outcomes for people with younger onset dementia

- Creating study groups based on subsequent permanent residential aged care use

6. General practitioner and specialist attendances

- Patterns of attendance while living in the community

- GP and specialist attendances before and after entry to permanent residential aged care

7. Prescriptions dispensed to people with younger onset dementia

- Patterns of dispensing over time while living in the community

- Prescriptions dispensed before and after entry to permanent residential aged care

8. Hospital services

- Use of hospital services while living in the community

- Hospital service use after entry to permanent residential aged care

9. Residential aged care services

- Respite residential aged care

- Permanent residential aged care

- Health conditions and changes in care needs

10. Causes of death

11. Discussion

- Linked data sets as a source of information on people with dementia

- Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety

- Future directions

Appendix A: People with evidence of younger onset dementia in the NIHSI AA 65

End matter: Acknowledgments; Abbreviations; Symbols; References; List of tables; List of figures; List of boxes