Autism

Autism spectrum disorder (also simply termed autism) is a persistent developmental disorder, characterised by symptoms evident from early childhood [8]. These symptoms include difficulty in social interaction, restricted or repetitive patterns of behaviour and impaired communication skills. However, these may not be recognised until later, when social demands, such as those related to schooling, become greater. There is no definitive test for autism; instead, diagnosis is made on the basis of developmental assessments and behavioural observations. This snapshot explores the prevalence and characteristics of people with autism, and their use of disability support services.

Prevalence of autism

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC), an estimated 164,000 Australians had autism in 2015 [5] (see also Box 1). This represented an overall prevalence rate of 0.7%, or about 1 in 150 people. The number of people with autism in Australia has increased considerably in recent years, up from an estimated 64,400 people in 2009 [3]. Of those who were estimated to have autism in 2015, 143,900 were identified as also having disability (88%) [5] (see also Box 1).

Box 1: Autism in the Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC)

In the SDAC, identification of autism is based on respondents who report autism or related disorders as a long-term condition—defined in SDAC as a condition which lasted, or was likely to last, for six months or more and was current at the time of the survey [4].

‘People with autism’ are defined in the ‘Prevalence of autism’ section as all those from the SDAC who reported autism or a related disorder as a long-term condition. People with autism may have more than one long-term condition, including conditions which cause a greater level of restriction than that which is caused by their autism.

In the SDAC, not all people with autism have disability—defined as a limitation, restriction or impairment which restricts a person’s everyday activities, and has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months [4]. Those that do have disability are referred to here as ‘people with autism and disability’.

The SDAC is designed to measure the prevalence of disability in Australia and the association with specific conditions, and does not provide a diagnostic assessment or estimates of specific health conditions. As such, it may under or over-estimate the overall prevalence of autism in Australia [3].

Demographics

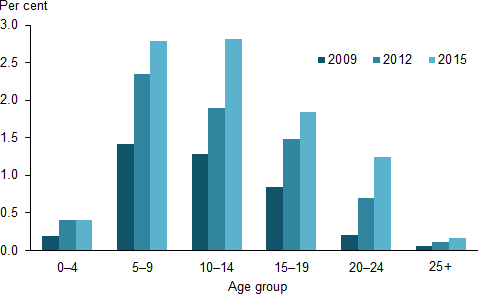

Autism is most commonly identified in children and young people. As such, people with autism were more likely to be younger, with 83% aged under 25 [5]. Autism was most prevalent among children aged 5 to 14 in 2009, 2012 and 2015, reflecting the general increase in diagnosis for school age children (Figure 1). This group has also experienced the greatest increase over time, though prevalence has increased across all age groups between 2009 and 2015. While it is not completely clear why the prevalence of autism is increasing, both higher levels of diagnosis and heightened awareness of the condition may have contributed to an increase in the reporting of autism-related disorders.

Figure 1: Prevalence of autism, by age group, 2009, 2012 and 2015

Notes

- The prevalence of autism is based on people with autism compared with the total population for the selected age group as estimated by SDAC. Rates are based on estimates generated by ABS TableBuilder and, as such, may differ from data published by the ABS because of confidentiality and perturbation processes.

- The estimated number of people with autism aged 0–4 in 2009, 2012 and 2015, and the estimated number of people with autism aged 20–24 in 2009 should be interpreted with caution due to the variability of small sample counts (relative standard error between 25% and 50%).

Sources: ABS 2010, ABS 2013, ABS 2016b.

Males were 4 times as likely as females to be reported as having autism, representing 81% of the population of people with autism.

Education and employment

People with autism may face barriers in education associated with their condition. In 2015, there were an estimated 83,700 children and young people (aged 5–20) with autism and disability, living in households and attending school. The majority (85%) reported difficulty at school, with more than 1 in 4 (28%) attending a special school [5]. The most common types of difficulty experienced were fitting in socially (63%), learning difficulties (62%) and communication difficulties (52%) (Table 1). Students with autism used various resources to support learning, with 56% receiving special tuition, and 44% using a counsellor or disability support person.

| Schooling difficulty | Per cent |

|---|---|

| Fitting in socially | 63 |

| Learning difficulties | 62 |

| Communication difficulties | 52 |

| Intellectual difficulties | 27 |

| Difficulty sitting | 18 |

Notes

- Table includes only people with autism and disability living in households and attending school. Data are based on estimates generated by ABS TableBuilder and, as such, may differ from data published by the ABS because of confidentiality and perturbation processes.

- People may experience more than one schooling difficulty.

Source: ABS 2016b.

People with autism may also face employment restrictions. In 2015, difficulty changing jobs or getting a preferred job was the most common restriction, reported by 50% of people with autism and disability of working age (15–64 years old) (Table 2). About 3 in 10 (29%) people with autism were permanently unable to work due to their condition or disability.

| Employment restriction | Per cent |

|---|---|

| Difficulty changing jobs or getting a preferred job | 50 |

| Restricted in type of job | 47 |

| Need for ongoing supervision or assistance | 30 |

| Restricted in number of hours | 29 |

| Permanently unable to work because of condition(s) | 29 |

Notes

- Table includes only people with autism and disability living in households. Data are based on estimates generated by ABS TableBuilder and, as such, may differ from data published by the ABS because of confidentiality and perturbation processes.

- People may experience more than one employment restriction.

Source: ABS 2016b.

Need for assistance with core activities

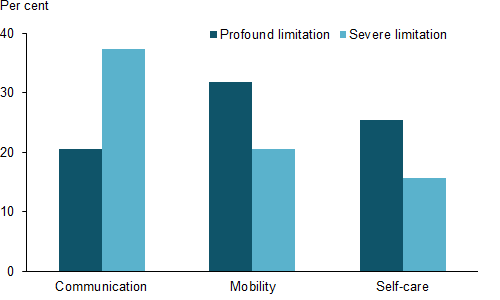

The symptoms of autism fall on a continuum—individuals can experience a mix of behaviours which can have a mild to profound impact on their day-to-day life. The majority of people with autism (65%) had a disability with a profound or severe limitation in core activities [5]. Core activity limitation refers to needing help or supervision with communication, mobility or self-care because of a person’s disability or long-term health condition. Around 58% of people with autism and disability had severe or profound restrictions in communication, which involves understanding or being understood by others (Figure 2). Profound or severe mobility limitations affected just over half of people with autism and disability (52%).

Figure 2: People with autism and disability, by profound and severe core activity limitation (communication, mobility and self-care), 2015

Note: Data are based on estimates generated by ABS TableBuilder and, as such, may differ from data published by the ABS because of confidentiality and perturbation processes.

Source: ABS 2016b.

Disability support services

A variety of government, not-for-profit and private services are available to people with autism to provide assistance in everyday life. Government services have commonly been provided under the National Disability Agreement (NDA) and the Helping Children with Autism program (for children aged under 7), but these will progressively transition to the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) over time. Not all people with autism access formal support services, and some may receive assistance through mainstream health and welfare services.

NDA services

Information on the use of services under the NDA is collected via the Disability Services National Minimum Data Set (DS NMDS), held by the AIHW. In 2014–15, there were around 43,500 NDA service users with autism as a primary or other significant disability, representing 13% of all NDA service users [7]. This was a 7% increase in the number of service users from 2013–14, when around 40,800 NDA service users reported autism as a primary or other significant disability (also representing 13% of all service users). In the DS NMDS, service users with autism are those who have been identified as having impairments or restrictions consistent with the broad disability group of ‘autism’, and are not based on the diagnosis of health conditions [7].

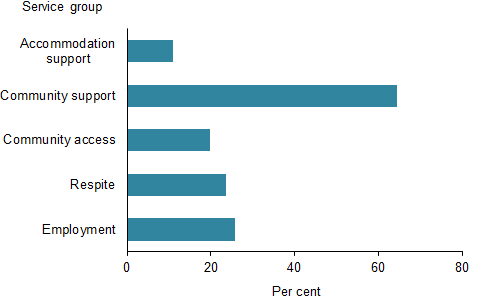

In 2014–15, the majority of NDA service users with autism used community support services (64%) (Figure 3). These services provide support to live in a non-institutional setting, and can include therapy support, early childhood intervention, and behaviour or specialist intervention. This was followed by employment services (26%), which provide assistance to obtain or retain paid employment in the open labour market, or provide supported employment opportunities and assistance. Respite services were used by 24% of service users, and provide temporary care to service users to assist in supporting and maintaining the primary care giving relationship.

Community access services were used by 20% of service users with autism. These provide opportunities for service users to gain skills and use their abilities to enjoy their full potential for social independence, such as learning and life skills development and recreation/holiday programmes. Accommodation support, used by 11% of service users, provides support for people with disabilities to remain in existing accommodation or move to more suitable accommodation.

Figure 3: NDA service users with autism, by service group, 2014–15

Note: Individuals may have used more than one service group over the 12 month period.

Source: DS NMDS 2014–15.

Age and sex

Almost 4 in 5 (79%) NDA service users with autism were aged under 25 and close to 2 in 5 (37%) were aged 5–14 years. Male service users outnumbered females by about 4 to 1—79% of service users with autism were male. Within each service group, males with autism made up a greater proportion of all service users than females with autism (Table 3).

| Service group | Males | Females | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation support | 15 | 6 | 11 |

| Community support | 24 | 10 | 19 |

| Community access | 21 | 9 | 16 |

| Respite | 34 | 16 | 27 |

| Employment | 11 | 3 | 8 |

| All service groups | 17 | 7 | 13 |

Note: Proportions of male and female service users are the percentage of service users of the specified sex within each service group.

Source: DS NMDS 2014–15.

Other disabilities

Many NDA service users with autism also reported other disabilities. These included:

- intellectual disability (33%)

- psychiatric disability (8%)

- specific learning disability or attention deficit disorder (7%)

- speech disability (6%)

- physical disability (5%)

- neurological disability (4%).

Need for assistance in life areas

The DS NMDS collects data on the level of need for assistance to perform activities in different life areas due to the person’s disability. A person’s need for assistance is evaluated in relation to a person of the same age without disability, and is an assessment of their need over and above that which would usually be expected due to their age [6]. In 2014–15, of NDA service users with autism:

- 73% always or sometimes needed help or supervision for self-care (such as washing oneself, dressing and eating)

- 91% always or sometimes needed help or supervision with interpersonal interactions and relationships

- 90% of those aged 5 and over always or sometimes needed help or supervision with education

- 80% of those aged 15 and over always or sometimes needed help or supervision in domestic life

- 91% of those aged 15 and over always or sometimes needed help or supervision in working life, which includes actions, behaviours and tasks to obtain and retain employment.

Informal care

An informal carer is a person, such as a family member, friend or neighbour, who provides regular and sustained care and assistance to the person requiring support. Informal carers delivered care and assistance on a regular basis for 84% of NDA service users with autism. The most common informal carers were the mother of the service users (88%), followed by their father (7%).

Employment and income

In 2014–15, many NDA service users aged 15 and over with autism were not in the labour force (42%). Almost 1 in 4 (24%) were employed and 1 in 3 (34%) were unemployed.

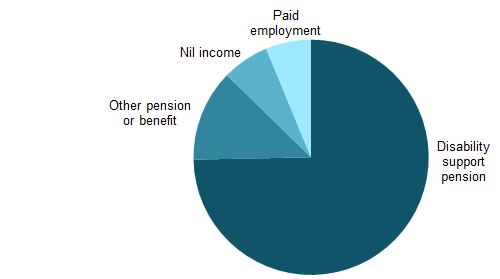

Around 3 in 4 service users aged 16 and over with autism (74%) received the disability support pension as their main source of income, and a further 13% received another pension or benefit (Figure 4). Only 6% reported paid employment as their main source of income.

Figure 4: Main source of income for NDA service users aged 16 and over with autism, 2014–15

Note: Less than 1% of service users reported ‘compensation payments’ or ‘other income’ as their main source of income.

Source: DS NMDS 2014–15.

Transition to the NDIS

Many people with autism who are currently receiving NDA services will transition to the National Disability Insurance Scheme as it rolls out. In 2013–14, 766 NDA service users with autism were reported in the DS NMDS as having transitioned to the NDIS, with another 364 reported in 2014–15. Service users with autism represented about one-fifth of all users who transitioned to the NDIS in each year.

Where to go for more information

Autism in Australia infographic

Information on people with disability from the 2015 ABS Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers is available from Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings, 2015 [4].

Information from the Disability Services National Minimum Data Set is available from the bulletin Disability support services: services provided under the National Disability Agreement 2014–15 [7].

Further information on government programs and services available to people with disability, including those with autism, is available from the Department of Social Services.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2010. Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers 2009, TableBuilder. Findings based on the use of TableBuilder data.

- ABS 2013. Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers 2012, TableBuilder. Findings based on the use of TableBuilder data.

- ABS 2014. Autism in Australia, 2012. ABS cat. no. 4428.0. Canberra: ABS.

- ABS 2016a. Disability, ageing and carers: summary of findings, Australia 2015. ABS cat. no. 4430.0. Canberra: ABS.

- ABS 2016b. Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers 2015, TableBuilder. Findings based on the use of TableBuilder data.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2016a. Disability Services National Minimum Data Set: data guide, July 2016. Cat. no. DAT 4. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2016b. Disability support services: services provided under the National Disability Agreement 2014–15. Bulletin 134. Cat. no. AUS 200. Canberra: AIHW.

- APA (American Psychiatric Association) 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition. Washington, DC: APA.