Summary

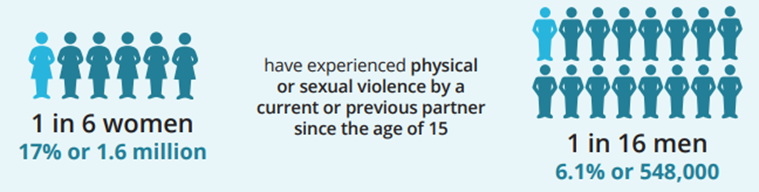

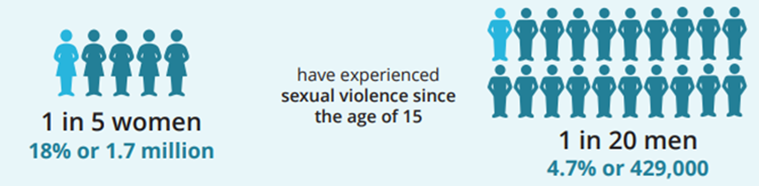

Family, domestic and sexual violence occurs every day, and can affect people of all ages and backgrounds. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ 2016 Personal Safety Survey:

Intervening with perpetrators and holding them to account is an important element of our efforts to prevent and reduce family, domestic and sexual violence. Holding perpetrators accountable for their violence is key to ensuring that families and communities are safe. Monitoring these interventions at a national level enables governments to keep track of what actions are being taken, and the outcomes achieved.

This report presents a conceptual overview of the outcome monitoring activities currently being undertaken across states and territories, and does not include data. It highlights similarities and differences in outcome monitoring approaches and informs government understanding of potential data improvements in this area that could be considered in future.

What are perpetrator interventions?

Perpetrator interventions are the responses that engage with a perpetrator directly because of their violence, or risk of perpetrating violence. This includes systems, structures and services which make decisions or orders that directly relate to perpetrators’ interactions with those against whom they have used violence. It also includes programmes and services targeted at working with perpetrators to enable them to change violent behaviours and attitudes.

How are perpetrator interventions monitored?

The National Outcome Standards for Perpetrator Interventions (NOSPI) were established as a core set of principles to guide the actions of governments, systems and services. They are captured by the following headline standards:

- Women and their children’s safety is the core priority of all perpetrator interventions

- Perpetrators get the right interventions at the right time

- Perpetrators face justice and legal consequences when they commit violence

- Perpetrators participate in programmes and services that change their violent behaviours and attitudes

- Perpetrator interventions are driven by credible evidence to continuously improve

- People working in perpetrator intervention systems are skilled in responding to the dynamics and impacts of domestic, family and sexual violence.

Outcomes and indicators developed to be consistent with these headline standards are used to measure and assess the performance of perpetrator interventions, and the perpetrator interventions system as a whole. Across states and territories, outcomes relating to perpetrator interventions are monitored in a variety of ways, including through the development of specific outcome frameworks, indicators and measures, or through regular reporting. Examples of these indicators and measures are presented in this report to assist readers to understand current practice and future planned improvements in reporting in this important area. Data against these indicators are not included in this report.

What do we know?

The National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–22 (National Plan) recognised the need to strengthen the evidence base for perpetrator interventions. Currently, the data available to report on perpetrator interventions are primarily sourced from police and courts. These data can be used to understand what happens when violence is detected by police and a perpetrator enters the justice system, however, they are only part of the picture. Information about police and court interactions related to family, domestic and sexual violence can be found in the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) collections, Recorded Crime—Offenders, and Criminal Courts, Australia. They have not been included here as this report presents a conceptual overview only, of the outcomes, indicators and measures currently being used by governments.

Where are the data gaps?

There are notable information gaps across the perpetrator interventions system, for example:

- Specialist perpetrator programs—there are limited data on behaviour change programs, or specialist FDSV services that have a perpetrator response. Where these data are available, they are collected and reported using different definitions and practices, and cannot be used to provide an overview of the sector.

- Perpetrator characteristics—there are limited data on characteristics such as age, sex, Indigenous status, country of birth. Detailed data on perpetrators can shed light on how violence is experienced or perpetrated differently across population groups, and can be used to show where perpetrators are likely to be misidentified, and who is in most need of protection.

- Data on children and young people—there are limited data on children and young people who experience and use FDSV. Children and young people should be considered in their own right as they may require different types of service responses to meet their needs and manage risk.

- Nationally consistent data—where data are being collected, there is limited scope to compare or aggregate data at a national level.

What has been done to improve data nationally?

Since the beginning of the National Plan, a range of activities have been undertaken to improve the collection and reporting of data on family, domestic and sexual violence. These activities include improving the capture of data on perpetrators in existing data collections (for example, in the AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Collection) and building or enhancing collections. However, additional opportunities exist to improve understanding of perpetrator interventions nationally, including greater use of linked data.

Summary

-

Introduction

- What are perpetrator interventions?

- National policy context

-

Monitoring the perpetrator interventions system

- State and territory outcome monitoring

-

Key concepts in perpetrator interventions

- Managing risk

- Victim safety, support and confidence in the system

- Family and domestic violence orders

- Justice and legal consequences

- Reoffending

- Specialist perpetrator programs

- Workforce capacity and capability

-

Data availability, limitations and development opportunities

- What data are available to report on perpetrator interventions at a national level?

- Data limitations

- What has been done to improve data at the national level?

- Future opportunities for data development and improvement

Appendix A: NOSPI indicators

Appendix B: NOPSI development and implementation

Appendix C: State and territory outcome measures and actions

End matter: References; Acknowledgments