Congenital heart disease

Page highlights:

How many Australians have congenital heart disease?

- In Australia, an estimated 65,000 children and adults live with congenital heart disease.

- In 2020–21, there were around 5,900 hospitalisations in Australia where congenital heart disease was the principal diagnosis.

In 2021, congenital heart disease caused 79 deaths in infants aged under 1 year, equivalent to 7.8% of all infant deaths.

In 2021, congenital heart disease caused 79 deaths in infants aged under 1 year, equivalent to 7.8% of all infant deaths.

What is congenital heart disease?

Congenital heart disease is a general term for any defect of the heart, heart valves or central blood vessels that is present at birth.

It can take many forms, such as holes between the pumping chambers of the heart, valves that do not open or close properly and narrowing of major blood vessels such as the aorta and pulmonary artery. Congenital heart disease can range from simple to complex, and more than 1 anomaly can occur in the same heart.

Diagnosis usually occurs within the first month of life. Common symptoms include bluish lips, fingers and toes, breathlessness or trouble breathing, low birth weight, difficulty feeding and gaining weight, and chest pain.

Most congenital heart disease is multifactorial and arises through combinations of genetic and environmental factors. Some of the known risk factors include a family history of congenital heart disease, maternal illnesses such as rubella (German measles), misuse of alcohol, illicit drugs and medications, and maternal health factors such as preeclampsia and poorly controlled diabetes.

The National Strategic Action Plan for Childhood Heart Disease aims to reduce the impact of congenital heart disease and other childhood heart diseases in Australia. It outlines priority areas and actions to help people with Childhood Heart Disease live longer, healthier and more productive lives.

How many Australians have congenital heart disease?

National rates of congenital heart disease are not routinely reported. Globally, an estimated 9.4 in every 1,000 live births were affected by congenital heart disease during the period 2010–2017 (Liu et al. 2019).

- In Australia, an estimated 65,000 children and adults live with congenital heart disease (Department of Health 2019).

- A number of Australian jurisdictions publish their incidence of congenital heart disease, noting that data collection methods vary (AIHW 2019, 2022). Ventricular septal defect was the most commonly reported congenital heart disease, followed by atrial septal defect and patent ductus arteriosus.

Main types of congenital heart disease

Ventricular septal defect – a hole in the muscle wall between the right and left ventricles.

Atrial septal defect – a hole in the muscle wall between the right and left atria.

Patent ductus arteriosus – where the ductus arteriosus, the connection between the aorta and pulmonary artery, fails to close after birth.

Tetralogy of Fallot – a condition that consists of 4 heart anomalies: ventricular septal defect, a narrowing of the outflow tract into the pulmonary artery, an enlarged aorta and thickening of the muscle wall of the right ventricle.

Transposition of great vessels – a condition that is usually characterised by the aorta arising from the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery from the left ventricle.

Coarctation of the aorta – narrowing of the aorta.

Aortic stenosis – obstruction of the aorta. This can be due to a narrowing of the aorta or a problem with the aortic valve.

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome – where the left ventricle is small and functionally inadequate.

Pulmonary atresia – a condition in which there is no pulmonary valve and no blood flow to the pulmonary artery.

Hospitalisations

In 2020–21, there were around 5,900 hospitalisations in Australia where congenital heart disease was the principal diagnosis – a rate of 23 hospitalisations per 100,000 population.

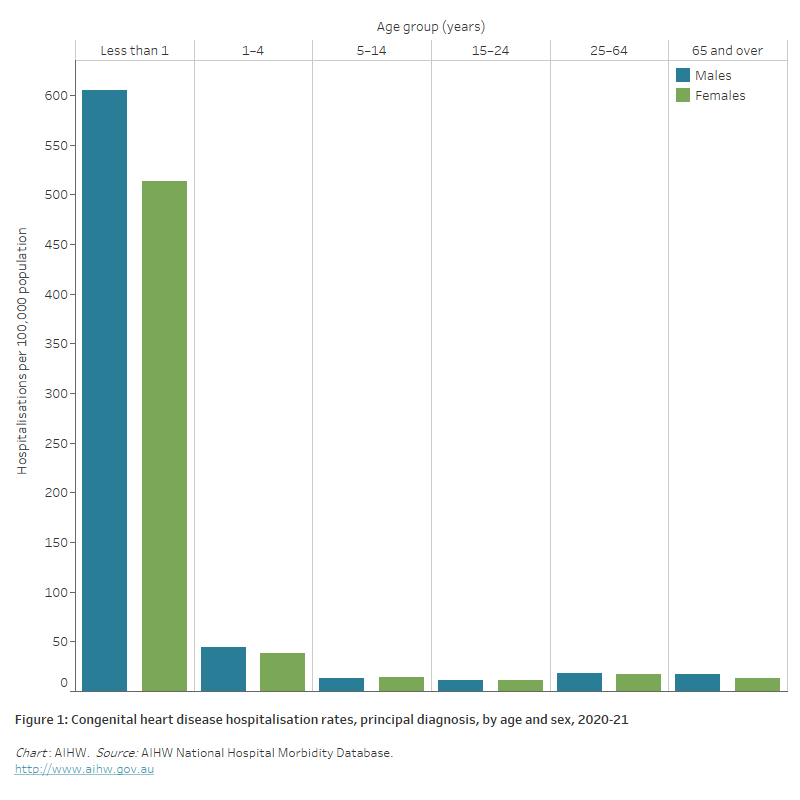

Age and sex

In 2020–21, where congenital heart disease was recorded as the principal diagnosis, hospitalisation rates:

- were similar for males and females after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations

- were highest for infant boys and girls (605 and 513 per 100,000 population), followed by boys and girls aged 1–4 (45 and 39 per 100,000 population)

Unlike many other cardiovascular conditions, the number and rate of hospitalisation for congenital heart disease declines with age (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Congenital heart disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows in 2020–21 congenital heart disease hospitalisation rates were highest among boys and girls aged less than 1, at 605 and 513 per 100,000 population, respectively.

Adults with congenital heart disease

Advances in paediatric cardiac care mean that people with congenital heart disease are now living longer, and the burden of disease is shifting from early childhood into the adult population (Celemajer et al. 2016).

Patients with complex and severe congenital heart disease will continue to require specialist treatment throughout their life. Often, they also require management of other health and welfare issues, including for family planning and pregnancy, lifestyle choices, dietary strategies, work choices and physical limitations.

In 2011, it was estimated that there were between 26,000 and 32,000 adults with congenital heart disease in Australia, with an annual increase of around 5% (Leggatt 2011).

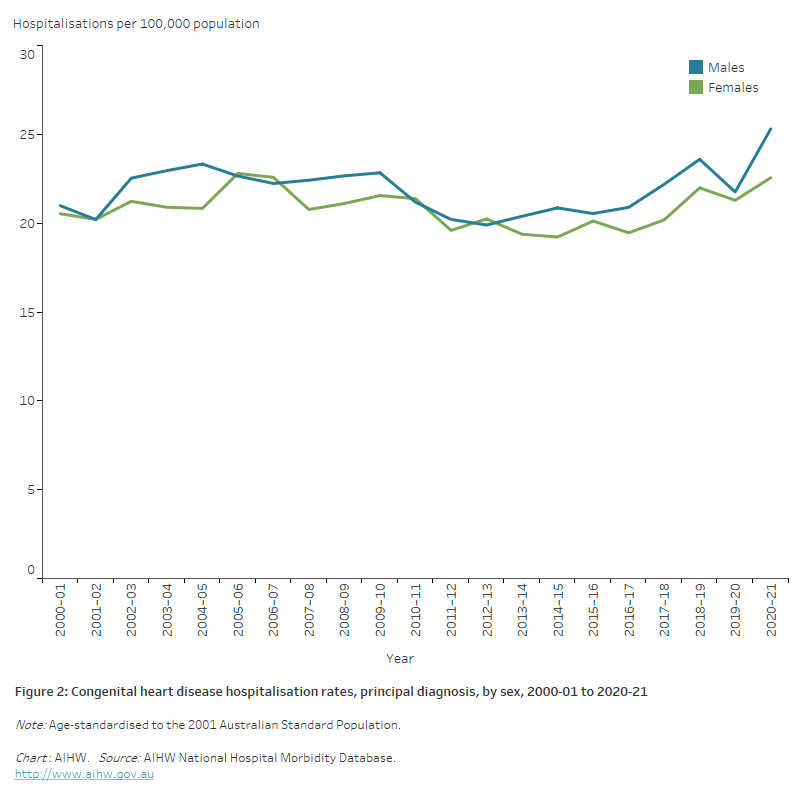

Trends

Between 2000–01 and 2020–21 the number of hospitalisations with congenital heart disease as a principal diagnosis increased from 4,000 to 5,900.

Over this period the age-standardised hospitalisation rate for congenital heart disease has changed little (21 per 100,000 in 2000–01 and 24 in 2020–21). Male and female rates are similar (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Congenital heart disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by sex, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The line chart shows age-standardised congenital heart disease hospitalisation rates remained relatively stable between 2000–01 and 2020–21 with males recording 20–25 and females recording 19–23 hospitalisations per 100,000 population across the period.

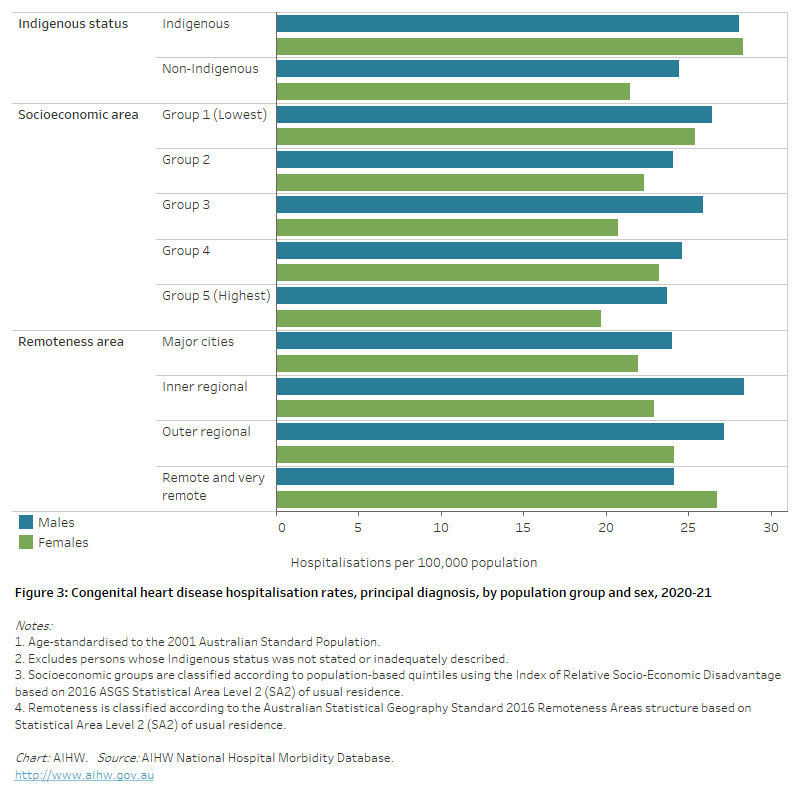

Variation among population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2020–21, there were around 340 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of congenital heart disease among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, a rate of 39 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations:

- the rate among Indigenous Australians was 1.2 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate.

Socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, the congenital heart disease hospitalisation rate was 1.2 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those in the highest socioeconomic areas, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations.

The difference was greater for females than males (1.3 and 1.1 times as high) (Figure 3).

Remoteness area

In 2020–21, congenital heart disease hospitalisation rates were 1.1 times as high among those living in Remote and very remote areas compared with those in Major cities, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations.

The difference was largely driven by disparities in female rates (1.2 times as high), with male rates being similar (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Congenital heart disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The horizontal bar chart shows that variation in age-standardised congenital heart disease hospitalisation rates among population groups was largely driven by higher rates among females. Rates were higher among Indigenous females than non-Indigenous females and females living in the lowest socioeconomic areas and Remote and very remote areas.

Procedures

About half of all babies born with congenital heart disease require surgical or catheter-based interventions to correct any defect, with one-third needing these interventions in the first year of life (Blue et al. 2012; Leggatt 2011).

Where congenital heart disease was the principal and/or additional diagnosis, there were almost 2,200 surgical procedures conducted in Australian hospitals for closure of an atrial septal defect in 2020–21, around 460 for closure of ventricular septal defect and 600 for closure of patent ductus arteriosus:

- procedure rates for infants aged under 1 year were 100 per 100,000 for closure of atrial septal defect, 109 per 100,000 for ventricular septal defect and 112 per 100,000 for patent ductus arteriosus in 2020–21

- most procedures for patent ductus arteriosus and ventricular septal defect were among children aged under 5 (69% and 82%)

- procedures for atrial septal defect were spread more evenly across ages, with 18% among children aged under 5 years, and 53% among adults aged 45 and over

- trends in procedure rates have changed little over the last decade – for atrial septal defect (6.2 and 8.3 per 100,000 in 2007–08 and 2020–21), ventricular septal defect (2.1 and 2.0 per 100,000 in 2007–08 and 2020–21) and patent ductus arteriosus (2.8 and 2.5 per 100,000 in 2007–08 and 2020–21).

Diagnostic and treatment options for congenital heart disease

Echocardiography – an ultrasound of the heart. This test is non-invasive and can be conducted before birth.

Pulse oximetry – a non-invasive test that measures the oxygen levels in the blood to see how efficiently the heart is pumping oxygen to the rest of the body.

Medications – often used for mild congenital heart defects, especially those found later in childhood or in adulthood. Medications can help the heart work more efficiently by lowering blood pressure, regulating the heartbeat or lowering the amount of fluid in the chest.

Cardiac catheterisation – a thin flexible tube is inserted into an artery in the leg and moved towards the heart to measure blood pressure and flow. Sometimes used in conjunction with imaging procedures including contrast studies and X-ray. Also a form of treatment to stretch narrowed vessels and valves, implant stents or close a hole.

Corrective surgery – usually reserved for more complex congenital heart conditions. There are many different procedures. Surgery is often undertaken in the first year of life.

Heart transplant – total replacement of the heart muscle.

Compassionate care – an alternative to surgery, often using palliation and other forms of end-of-life care.

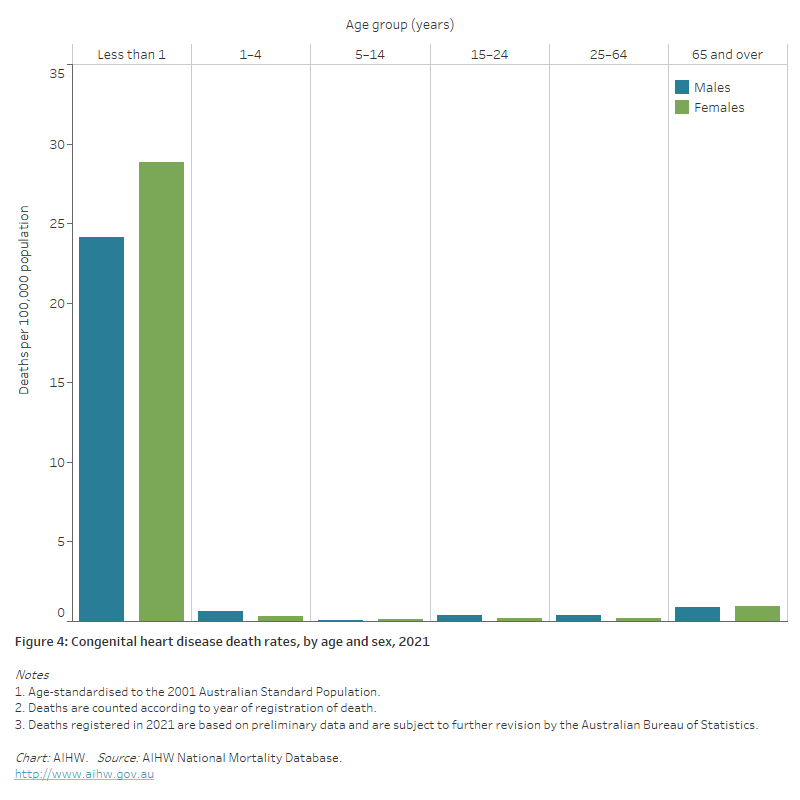

Deaths

In 2021, congenital heart disease was the underlying cause of >171 deaths (0.1% of all deaths) in Australia – a rate of 0.7 deaths per 100,000 population.

Congenital heart disease is a leading cause of death among infants. In 2021, congenital heart disease caused 79 deaths in infants aged under 1 year, equivalent to 7.8% of all infant deaths.

Age and sex

In 2021, 90 males and 81 females died as a result of congenital heart disease, equivalent to age-standardised rates of 0.7 and 0.6 per 100,000 population (Figure 4). Of these:

- 46% were aged less than 1 year (37 boys and 42 girls)

- 11% were aged 1–24 (11 males and 7 females)

- 20% were aged 25–64 (24 males and 11 females)

- 23% were aged 65 or over (18 males and 21 females).

Figure 4: Congenital heart disease death rates, by age and sex, 2021

The bar chart shows in 2021 congenital heart disease death rates were highest among boys and girls aged less than 1, at 24 and 29 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively.

Trends

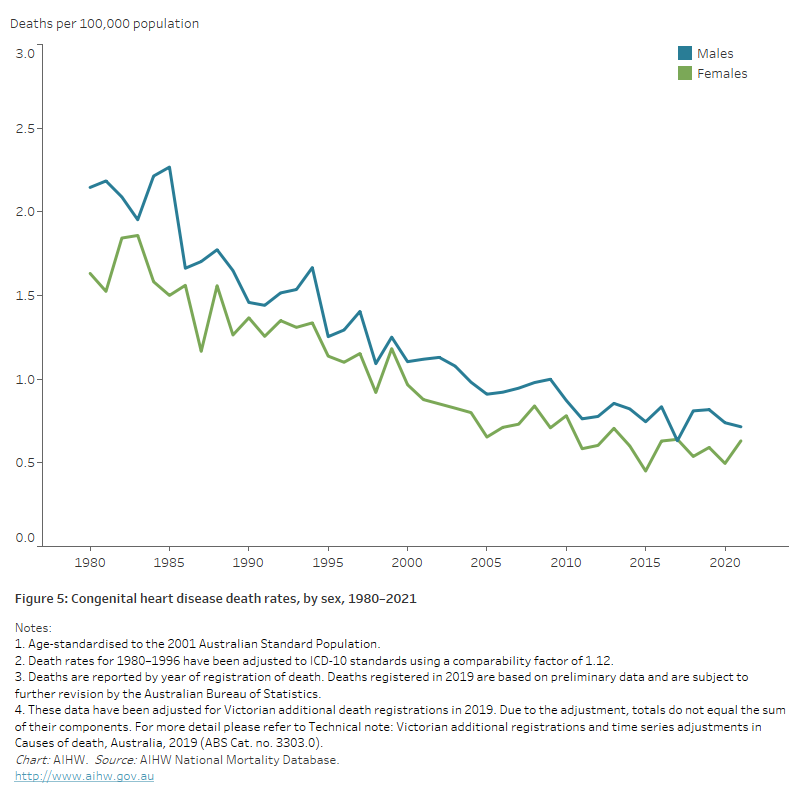

Both the number and rate of congenital heart disease deaths declined between 1980 and 2021:

- the number of congenital heart disease deaths declined by 45%, from 310 to 171

- the age-standardised congenital heart disease death rate declined by almost two-thirds, falling from 1.9 to 0.7 deaths per 100,000 population. Congenital heart disease death rates declined in a similar fashion for males and females (Figure 5).

In 1987, 71% of congenital heart disease deaths occurred in children aged under 5 years. By 1997, this figure had fallen to 55%, falling further to 50% in 2007 and in 2021.

Fewer deaths as a result of treatment improvements and an increase in the number of terminations of pregnancies after antenatal diagnosis have been suggested as factors that have contributed to the decrease in mortality rates (Leggatt 2011).

Figure 5: Congenital heart disease death rates, by sex, 1980–2021

The line chart shows age-standardised congenital heart disease death rates declined between 1980 and 2021, from 2.1 to 0.7 and 1.6 to 0.6 per 100,000 population for males and females, respectively.

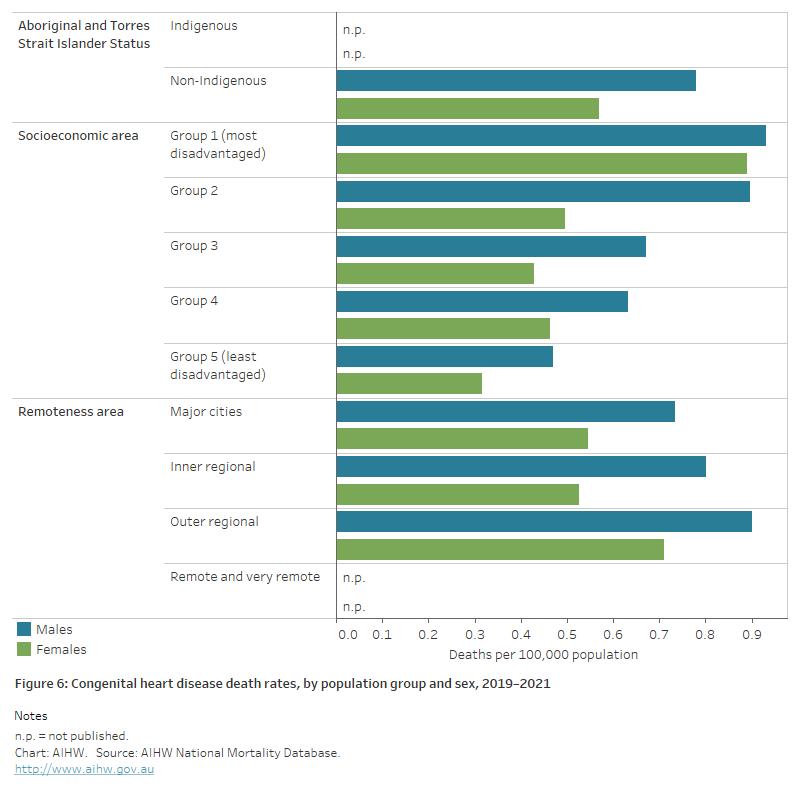

Variation among population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2019–2021, there were 29 deaths from congenital heart disease among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in jurisdictions with adequate identification of Indigenous status, a rate of 1.3 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, the congenital heart disease death rate for Indigenous people was 1.7 times as high as for non-Indigenous people (Figure 6).

Socioeconomic area

In 2019–2021, the age-standardised congenital heart disease death rate in the lowest socioeconomic areas was 2.3 times as high as in the highest socioeconomic areas (Figure 6).

Remoteness area

In 2019–2021, the age-standardised congenital heart disease death rates in Major cities, Inner regional and Outer regional areas were similar (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Congenital heart disease death rates, by population group and sex, 2019–2021

The horizontal bar chart shows in 2019–2021, age-standardised congenital heart disease death rates were similar among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Rates were slightly higher in the lowest socioeconomic areas, and among people living in Outer regional and Remote and very remote areas.

AIHW (2019) Congenital heart disease in Australia. AIHW cat. no. CDK 14. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2022) Congenital anomalies 2016. AIHW cat. No. PER 119. Canberra: AIHW.

Blue GM, Kirk EP, Sholler GF, Harvey RP & Winlaw DS (2012) Congenital heart disease: current knowledge and causes and inheritance. Medical Journal of Australia 197:155–9.

Celermajer D, Strange G, Cordina R, Selbie L, Sholler G, Winlaw D et al. (2016) Congenital heart disease requires a lifetime continuum of care: a call for a regional registry. Heart, Lung, and Circulation 25:750–4.

Department of Health (2019) Beyond the heart: transforming care. National Strategic Action Plan for Childhood Heart Disease. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Leggatt S (2011) Childhood heart disease in Australia. Current practices and future needs. Sydney: HeartKids Australia.

Liu Y, Chen S, Zuhlke L, Black GC, Choy M, Li N et al. (2019) Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970–2017: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. International Journal of Epidemiology 48:455–63.