Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use in 2015–16

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2022) Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use in 2015–16, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use in 2015–16. Retrieved from https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-drug-alcohol-use-2015-16

MLA

Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use in 2015–16. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 June 2022, https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-drug-alcohol-use-2015-16

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use in 2015–16 [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022 [cited 2024 Apr. 19]. Available from: https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-drug-alcohol-use-2015-16

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2022, Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use in 2015–16, viewed 19 April 2024, https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-drug-alcohol-use-2015-16

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

On this page:

Study cohort – Specialist homelessness services: Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use in 2015–16

Introduction

Problematic drug or alcohol use and homelessness are often intertwined. In addition, these clients also often experience other vulnerabilities, such as family and domestic violence and mental health issues which can lead to housing instability and homelessness (see Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use).

Longitudinal analyses have been undertaken for a cohort of clients with problematic drug or alcohol use in 2015–16. These analyses are designed to examine SHS service usage patterns for a cohort of service users that can be tracked for a relatively similar period in the past and into the future.

See Introduction to the SHS longitudinal data for details on the longitudinal analysis undertaken.

The problematic substance use issues (SUB) 2015–16 SHS client cohort was defined as SHS clients that met any of the following conditions in any of the support periods in 2015–16:

- recorded their dwelling type as rehabilitation facility

- required drug or alcohol counselling

- were formally referred to the SHS from an alcohol and drug treatment service

- had been in a rehabilitation facility or institution during the past 12 months

- reported problematic drug, substance or alcohol use as a reason for seeking assistance or the main reason for seeking assistance

- the identification of clients with problematic drug and/or alcohol use may be current or recent; referring to issues at presentation, just prior to receiving support or at least once in the 12 months prior to support.

The above approach is consistent with the definition for clients with problematic drug and/or alcohol use in other AIHW SHS publications such as the 2020–21 SHS annual report (AIHW 2021).

Note that, because the criteria for inclusion in the problematic drug and/or alcohol use cohort includes whether the client had been in a rehabilitation facility or institution during the past 12 months, it is possible that some clients in the cohort do not actually have substance use issues in the defining study period (and do not require services for substance use issues) but had these issues only in the past.

The longitudinal analyses are limited to adult clients (aged 18 and over). This is because the longitudinal analyses focus on pathways for individual clients, whereas children accessing services may need support because of issues that are unrelated to them directly.

A comparison cohort (non-SUB cohort) was also created, comprising clients aged 18 and over who did not meet the criteria for inclusion in the DA cohort. These clients did not meet any of the above conditions in any of the support periods during their defining study period (12 months from the start of their first support period in 2015–16). They were therefore considered to have not had problematic drug and/or alcohol use issues in their defining study period. More information on the how comparison cohorts were derived can be found in the Methodology section.

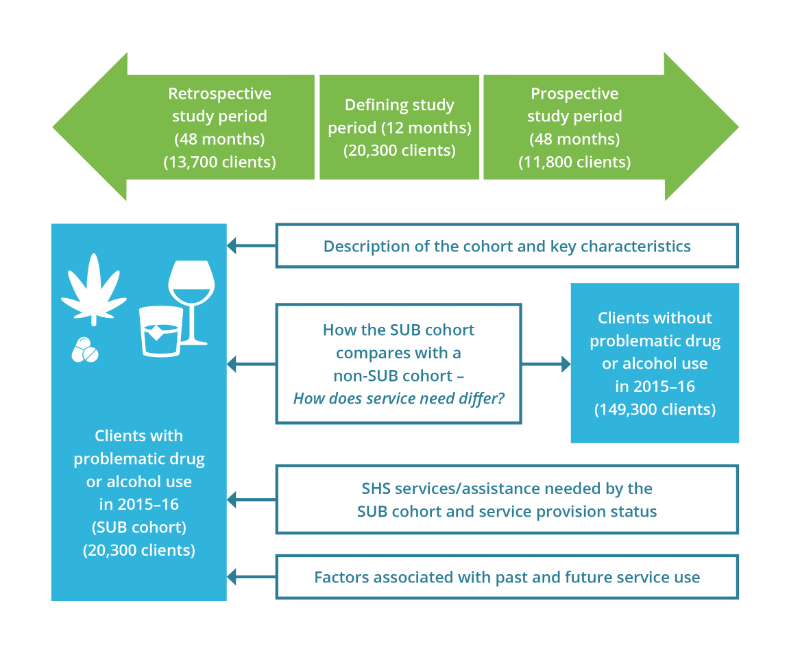

The longitudinal SHS data for the period 2011–21 were used to (Figure SUB.1):

- examine characteristics of clients with problematic drug and/or alcohol use (termed the SUB cohort) compared with the comparison cohort (the non-SUB cohort)

- examine outcomes for the SUB cohort in terms of historical and future service use.

The retrospective study period for this cohort is the 48 months before the start of the defining study period (that is, the 12 months from the start of their first mental-health related support period in 2015–16). The prospective study period is the 48 months after the end of each client’s 12 month defining study period.

Figure SUB.1: Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use cohort, longitudinal analysis overview

Source: AIHW analysis of SHS longitudinal data 2011–21, Table SUB1516.1.

Key characteristics of the SUB 2015–16 cohort

There were nearly 20,300 clients in the SUB 2015–16 SHS client cohort with the following key characteristics (Table SUB1516.1):

- The mean age of clients was 35 years with over 29% (nearly 6,000 clients) aged 25–34 years and 28% (nearly 5,800 clients) aged 35 to 44 years at the time of their first substance-use-related support period in 2015–16.

- Around 6,300 clients (31%) were Indigenous.

- Nearly 2,300 clients (11%) were born overseas.

- Around 42% of clients (8,500 clients) had only one support period during the defining study period and 36% (7,300) had 3 or more support periods.

- Over 67% had received SHS support previously; that is, nearly 13,700 clients had received SHS support in the 48-month retrospective period that preceded the defining study period. Of these clients, 6,500 clients (32% of the SUB 2015–16 cohort or alternatively 48% of clients that used services in the past) had problematic substance use issues during a historical period of support.

- Over 58% of clients (11,800) continued to receive SHS support into the future; that is, they received support in the 48 months after the 12-month defining study period. Of these clients, nearly 6,400 (31% of the SUB 2015–16 cohort, or alternatively 54% of clients that continued to use services into the future) had problematic substance use issues during a future period of support.

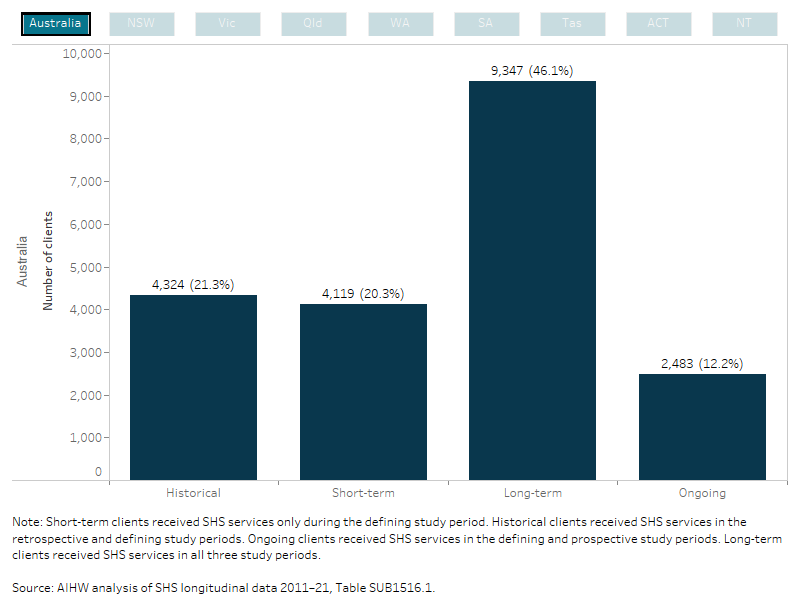

Service engagement profiles

Service use patterns of the SUB cohort over the entire longitudinal period (2011–21) were examined. Almost half (9,300 or 46%) of SUB cohort clients had used SHS support over the 10-year longitudinal period (long-term clients) (Figure SUB.2, Table SUB1516.1).

Figure SUB.2: SUB client cohort 2015–16, service engagement profiles

This interactive bar chart shows service use patterns of the SUB cohort over the entire longitudinal period (2011–21). Support information was combined from the discrete study periods into four service engagement profile groups (historical, short-term, long-term and ongoing). Engagement profiles for all states and territories and Australia can be selected and displayed. Nationally, of the 20,300 clients that made up the study period cohort, almost half (9,300 or 46%) of SUB cohort clients had used SHS support over the 10-year longitudinal period (long-term clients). For ACT clients, 37% were short-term clients and had used SHS support during the defining period only and a small proportion (7%) were ongoing clients (used services in the defining and prospective periods).

How the SUB cohort compares with a non-SUB cohort

Key comparisons between the SUB and non-SUB clients receiving SHS support in 2015–16 include (Figure SUB.3, Table SUB1516.1):

- The age profile of clients was similar between the two cohorts.

- SUB clients were more likely to be male (55% compared with 34% of non-SUB clients).

- During the defining study period, SUB clients were much more likely to have experienced homelessness (75% compared with 47%) and much more likely to have had mental health issues (69% compared with 28%).

- Nearly all clients in the SUB cohort (96%) were not employed (that is, unemployed or not in the labour force) at some time during the defining study period compared with 78% of clients in the non-SUB cohort. They were more likely (12% compared with 3%) to be transitioning from custody (12% compared with 3%).

- Both groups were equally likely to have experienced FDV (around 35 to 37%).

- SUB clients were more likely to have had 3 or more support periods in the defining study period (36% of clients compared with 20%) and 17% less likely to have had only one support period than non-SUB clients. This finding may be related to the overall need for support relative to non-SUB clients or may be a function of the type of support these clients need (see section How did service needs differ?). Services provided to SUB clients may be more likely to be sporadic or recurrent than other services. It is not necessarily indicative of a greater need for services than non-SUB clients.

- SUB clients were much more likely to have received accommodation (51% compared with 24%). They also received many more nights of accommodation than non-SUB clients; during the 12-month defining study period SUB clients received an average of 51 nights of accommodation, whereas non-SUB clients received 20 nights. During the retrospective period, SUB clients received over twice as many nights of accommodation on average (44 compared with 19) than non-SUB clients and in the prospective period they received more than twice as many nights on average (35 compared with 13 nights).

- SUB cohort clients were much less likely to be short-term clients (20% compared with 41%), meaning that they were less likely to have only received SHS support in the defining study period. They were roughly 22% more likely (46% compared with 25%) to be long-term clients (meaning they received SHS support in the past and in the future).

- One-third of the SUB cohort (32%) had problematic drug or alcohol use identified when they received support in the past, compared with only 6% of non-SUB clients. Nearly one-third (31%) of clients had problematic drug or alcohol use during future use of services, compared with 7% of non-SUB clients.

Figure SUB.3: SUB and non-SUB cohort, client key characteristics, by study period, 2015–16

This interactive bar chart shows a comparison between the SUB and non- SUB cohorts, in terms of key characteristics and across all study periods (defining, retrospective and prospective). A radio button allows selection for the individual state/territory and Australia. For Australia, the SUB cohort had a similar age profile to the non- SUB cohort, however clients in the SUB cohort were more likely to be male; 55% compared with 34% for the non- SUB cohort. Nearly all clients in the SUB cohort (96%) were not employed (that is, unemployed or not in the labour force) at some time during the defining study period compared with 78% of clients in the non-SUB cohort.

How did service needs differ?

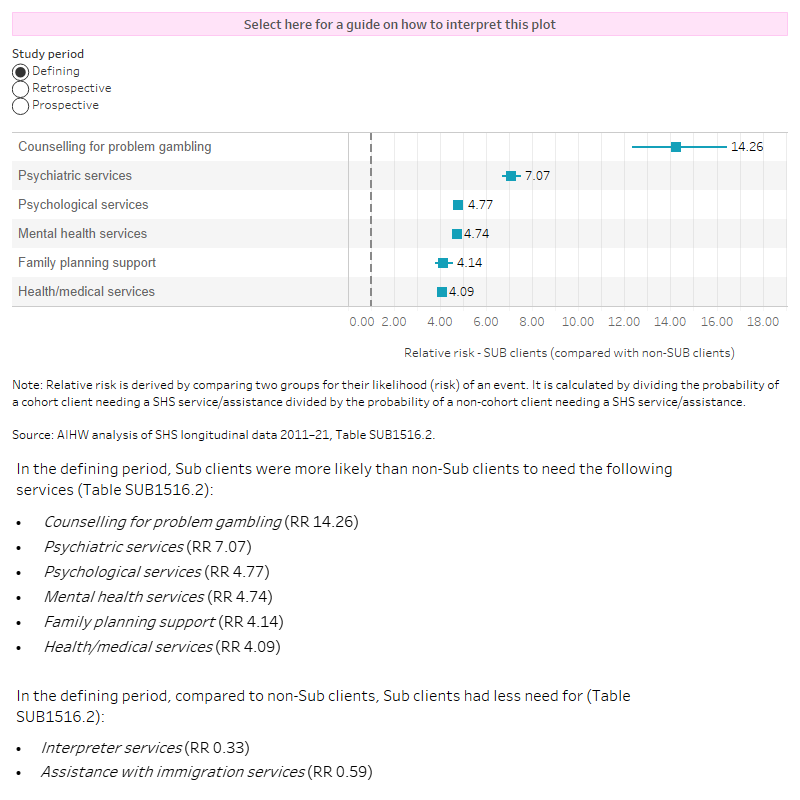

Differences in identified service need between the 2015–16 SUB and non-SUB SHS client cohorts were examined using relative risk, which was calculated by dividing the risk of an event occurring for one group (specifically, service need for each service type separately for SUB clients) by the risk of an event occurring for another group (service need for non-SUB clients).

Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use were over 14 times more likely to need counselling for problem gambling (relative risk (RR) 14.26) during the 2015–16 defining study period than clients in the non-SUB cohort (Figure SUB.4; Table SUB1516.2).

The diversity in the services shown below demonstrates that SUB clients have very diverse needs and that the need for mental health-related services was very common among the SUB cohort.

Figure SUB.4: Relative risk of needing a SHS service type, SUB and non-SUB clients, by study period, 2015–16

The interactive risk ratio plot shows the differences in service need between SUB and non- SUB clients receiving SHS support in each study period, these associations are presented as relative risks. The top 6 services more likely to be needed by SUB cohort clients compared with non- SUB clients (that is, those with the largest relative risk) have been shown in the figure. A radio button allows selection of the services and relative risks for each of the study periods (defining, retrospective and prospective). Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use were over 14 times more likely to need counselling for problem gambling (relative risk (RR) 14.26) during the 2015–16 defining study period than clients in the non-SUB cohort.

SHS clients – SUB cohort past and future service use

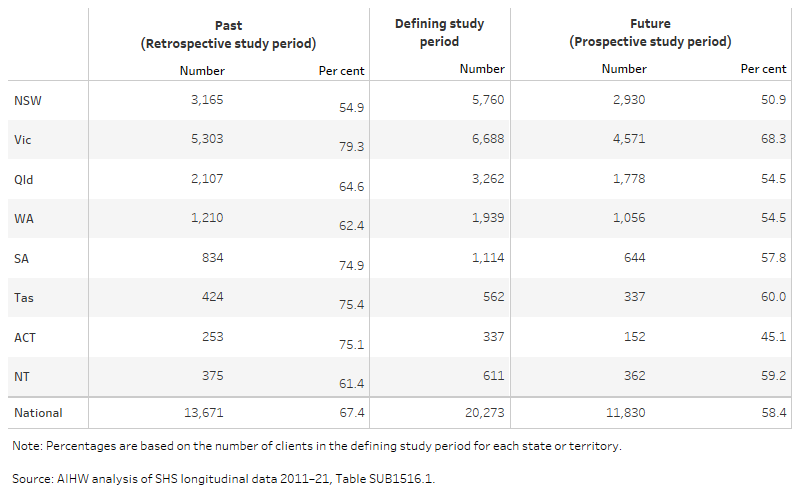

Services provided by SHS agencies was examined for the 2015–16 SUB cohort in each study period (Table SUB.1, Table SUB1516.1). One third (33%; 6,700) of clients received their first support period in 2015–16 from agencies located in Victoria, followed by 28% in New South Wales and 16% in Queensland.

The proportion of clients that received SHS support in the past ranged from 55% of the cohort in New South Wales to 79% of the cohort in Victoria. The proportion of clients that received SHS support in the future (after the defining study period) ranged from 45% in the ACT to 68% in Victoria.

Table SUB.1: SUB clients 2015–16, by past (retrospective) and future (prospective) service use and state/territory

The table image shows the number and per cent of SUB cohort clients within each study period for each state and territory and Australia. One third (33%; 6,700) of clients received their first support period in 2015–16 from agencies located in Victoria, followed by 28% in New South Wales and 16% in Queensland. The proportion of clients that received SHS support in the past ranged from 55% of the cohort in New South Wales to 79% of the cohort in Victoria. The proportion of clients that received SHS support in the future (after the defining study period) ranged from 45% in the ACT to 68% in Victoria.

SHS services needed by SUB cohort clients

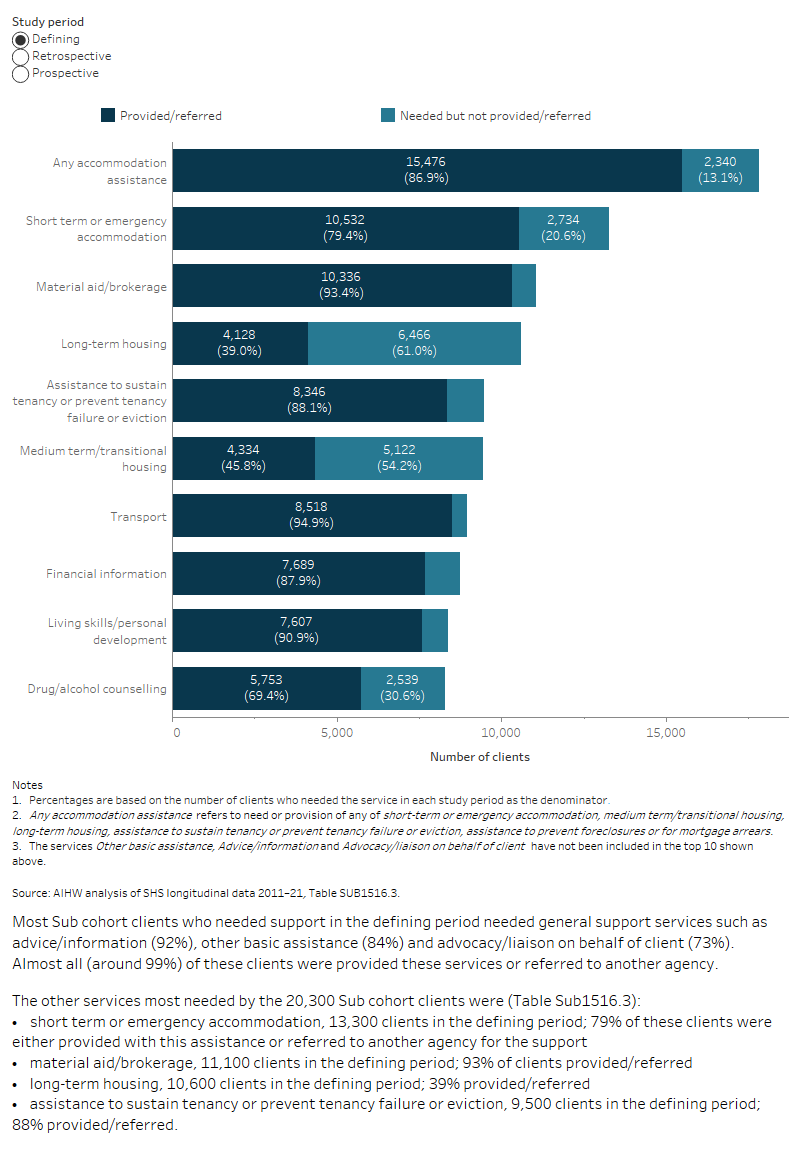

Service need and service provision/referral was examined for the SUB 2015–16 SHS clients that used services in the retrospective, defining and prospective study periods; aggregation is based on services needed or provided/referred in support periods that commenced within each study period only.

Patterns of service need were generally similar for the 2015–16 SUB cohort across the 3 study periods. For example, the proportion of clients with a need for accommodation assistance (all forms) was similar and pervasive (around 89%) in all study periods (Figure SUB.5, Table SUB1516.1, Table SUB1516.3).

Although a need for drug or alcohol counselling is one of the criteria for clients being included in this cohort, only 41% of clients in the defining study period required this service, and only 26% of the cohort required this service in the retrospective or the prospective period.

Figure SUB.5: SUB clients, select top 10 services and assistance needed and service provision status by study period

|

The interactive stacked horizontal bar graph shows the select top 10 services needed and the provision/referral status for the SUB cohort clients (20,300 clients) that used services in the retrospective, defining and prospective study periods. Patterns of service need were generally similar for the 2015–16 SUB cohort across the three study periods. For example, the proportion of clients with a need for accommodation assistance (all forms) was similar and pervasive (around 89%) in all study periods. |

Factors associated with past and future SHS service use

Descriptive regression models were used to examine whether client characteristics or support experiences in the defining period were associated with receipt of SHS support in the prospective study period (ongoing service use) or, separately, in the retrospective period (historical service use). Information on interpreting regression models can be found in the section Understanding factors associated with past and future support.

Some bias is present in this outcome measure because some clients that required services in the future may not have been able to receive them (see the section on Bias within the SHSC longitudinal data).

What client characteristics are associated with using SHS services in the retrospective study period?

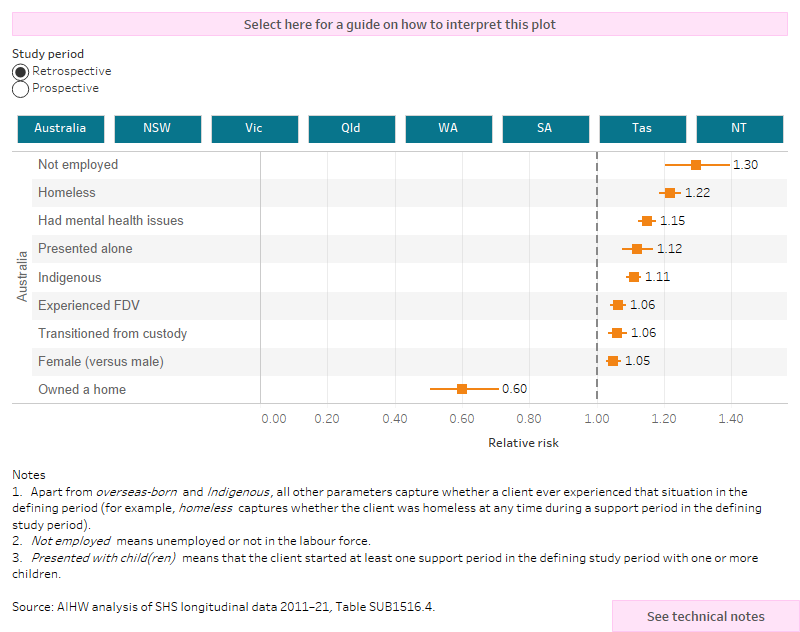

Some client characteristics or circumstances are associated with the SHS support in the past (relative to the defining study period). However, variations in state-territory specific policy and service deliver models mean that the likelihood of a client receiving support in the future varies among states or territories. Therefore, in addition to a national model, separate regression models were created for each state or territory where there was sufficient sample size. The models are descriptive, that is, they are intended to describe the client variables that are associated with past or future service use without proposing or testing specific causal pathways.

The outcome variable (receipt of SHS support) was a binary measure (yes or no) and did not distinguish between clients that needed SHS service types only once in the retrospective study period and clients that required frequent support.

Risk ratios were created to measure the association between the use of SHS services and a set of client characteristics (see Glossary entry on Relative risk for how to interpret the results).

Model results are shown in Figure SUB.6, which shows relative risk for having received SHS support in the past and, separately, in the future for chosen client variables. Separate models were created for each state or territory, as well as a national model. Results should be used with caution for states or territories where there were too few clients (less than 3,500) in the cohort for a meaningful model (Table SUB.1). Data from these states or territories are included in the national results, though it is important to recognise that the national data are mostly a reflection of the associations in the largest states. Therefore, while the national data are comprehensive and reflect the pathways of all clients in Australia, they are strongly influenced by the New South Wales and Victorian experience (which together account for 61% of clients) and somewhat insensitive to the situation in the smaller states or territories.

The results show that having owned a home was associated with reduced likelihood of having a history of SHS support (40% reduced likelihood in the national data; Figure SUB.6, Table SUB1516.4), although the associations vary in magnitude within each state or territory. Most other factors were associated with having a history of SHS support, especially not being employed (30% greater likelihood), having been homeless (22% greater likelihood), having mental health issues (15% greater likelihood).

Being an Indigenous Australian also had a strong association (11% increased likelihood) with past SHS support. This is partly due to the social and economic disadvantages faced by Indigenous Australians and a higher prevalence of health risk factors (POA 2014, AIHW 2020).

Figure SUB.6: SUB clients 2015–16, Relative risk for use of SHS services in the retrospective and prospective study periods

The interactive risk ratio plot shows the characteristics or circumstances that are associated with the SUB cohort clients use of SHS services in the past (retrospective) or future (prospective period), these associations are presented as relative risks. Relative risks for all states and territories and Australia can be selected and displayed. The results show that having owned a home was associated with reduced likelihood of having a history or ongoing use of SHS support, although the associations vary in magnitude within each state or territory. Most other factors were associated with a greater likelihood of past and future SHS support, especially not being employed, having been homeless, having mental health issues.

What client characteristics are associated with using SHS services in the prospective study period?

Descriptive regression models were used to examine the association between SHS SUB 2015–16 cohort client characteristics and future SHS support. Similar to the models for past SHS support, analyses were undertaken using national data and separately for states or territories with sufficient sample sizes (at least 3,500 clients; Table SUB.1, Figure SUB.6, Table SUB1516.4).

The results for future SHS support largely mirror those for associations with past SHS support. Although different in magnitude in each state or territory, not being employed at some time in the defining study period – specifically, being unemployed or not in the labour force – had the greatest association with future SHS support. Nationally, clients not employed in at least one support period during the defining period were 37% more likely to receive SHS support in the future.

Other factors associated with an increased likelihood of ongoing SHS support include being homeless at some time (27%) and having mental health issues (15%). Being an Indigenous Australian also had a strong association (26% increased likelihood in the national data) with future SHS support.

Conversely, owning a home at some time in the defining study period is associated with a reduced likelihood (22% less likely).

Summary

Over 20,200 SHS clients in 2015–16 had problematic drug and/or alcohol use. Over half of the clients were male (55%), around a third were Indigenous (31%) and more than two-thirds (67%) had used services previously.

Compared with clients without drug or alcohol issues, this cohort was more likely to have experienced homelessness in the defining study period and have mental health issues. Around 1 in 8 were transitioning from custody.

Clients with problematic drug and/or alcohol use had more periods of support compared with other clients and were twice as likely to receive accommodation support; they also received more than twice as many nights of accommodation, on average.

Compared with clients without problematic drug or alcohol use, these clients were more likely to require counselling for problem gambling and to require psychiatric, psychological or mental health services.

Among clients with problematic drug and/or alcohol use, those that were not in the labour force in the defining study period were more likely to have received SHS support in the past or in the future, as were Indigenous clients or those that had experienced homelessness or had mental health issues. Having owned a home was associated with a reduced likelihood of SHS support in the past or future.

AIHW (2016) Exploring drug treatment and homelessness in Australia: 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2014. AIHW Cat. no. CSI 23. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra.

AIHW (2020) Health risk factors among Indigenous Australians. Australia's health 2020: snapshots. Australia’s health series no. 17 Cat. no. AUS 232. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2021) Specialist homelessness services annual report. AIHW Cat. no. HOU 322. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra.

Chamberlain C & Johnson G (2011) Pathways into adult homelessness. Journal of Sociology, vol. 49 issue 1, pp. 3-21.

Duff C, Hill N, Blunden H, Valentine K, Randall S, Scutella R and Johnson G (2021) Leaving rehab: enhancing transitions into stable housing, AHURI Final Report No. 359, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Johnson C & Chamberlain G (2008) Homelessness and substance abuse: which comes first? Australian Social Work, 61(4).

Lalor E (2020) Inquiry into Homelessness in Victoria: Submission to Legal and Social Issues Committee Legislative Council Parliament of Victoria. North Melbourne, Vic: Alcohol and Drug Foundation.

McVicar D, Moschion J & van Ours J. C (2015) From substance use to homelessness or vice versa?. Social Science & Medicine, 136, pp.89-98.

Nilsson SF, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C (2019) Individual level predictors for becoming homeless and exiting homelessness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Urban Health. vol. 96 issue 5, pp. 741-50.

POA (Parliament of Australia) (2004) A hand up not a hand out: Renewing the fight against poverty. Report on Poverty and Financial Hardship. Canberra: Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee.

Scutella R, Chigavazira A, Killackey E, Herault N, Johnson G, Moshcion J & Wooden M (2014) Journeys Home Research Report No. 4 Findings from Waves 1 to 4: Special Topics. University of Melbourne.

Vallesi S, Tuson M, Davies A, Wood L (2021) Multimorbidity among People Experiencing Homelessness—Insights from Primary Care Data International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 18, issue 12, p. 6498.