Health of mothers and babies

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Health of mothers and babies, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 25 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Health of mothers and babies. Retrieved from https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/health-of-mothers-and-babies

MLA

Health of mothers and babies. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 23 November 2023, https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/health-of-mothers-and-babies

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health of mothers and babies [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 25]. Available from: https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/health-of-mothers-and-babies

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Health of mothers and babies, viewed 25 April 2024, https://pp.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/health-of-mothers-and-babies

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

The health of both mothers and babies can have important long-term implications. Maternal demographics, such as maternal age and country of birth, can impact on maternal and perinatal health. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle during pregnancy and attending routine antenatal care contributes to better outcomes for both mother and baby. The health of a baby at birth is a key determinant of their health and wellbeing throughout life, with poorer outcomes generally reported for those born early and with low birthweight (below 2,500 grams).

This page uses data from the National Perinatal Data Collection (NPDC) (AIHW 2021) and other related perinatal collections to explore aspects of pregnancy and childbirth as well as key outcomes for babies at birth. For more information on data sources used in this page, and to see a full list of AIHW products that focus on mothers and babies, see Data sources and Reports.

Profile of mothers and babies

About 311,400 women gave birth to around 315,700 babies in 2021. This is the highest number of births on record and about 20,000 more than in 2020 (an increase of 6.7%). In 2021, the rate of women of reproductive age (aged 15 to 44 years) giving birth also increased to 61 per 1,000 women compared with a decreasing trend over the past decade (from 64 per 1,000 women in 2011 to 56 per 1,000 in 2020).

In 2021:

- 73% of mothers lived in Major cities.

- 34% of mothers were born overseas.

- 19% of mothers were from the lowest socioeconomic areas.

- 5.0% of mothers were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people.

- 51% of babies born were male, with a ratio of 105 live-born boys to 100 live-born girls.

- 6.1% of babies born were First Nations people.

Detailed information on mothers and babies from population groups, such as First Nations people or those from remote areas, is available from Australia’s mothers and babies and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers and babies.

Mothers

Figure 1: Health factors of mothers, 2011 (or earliest available year) to 2021

The chart shows the proportion of mothers by maternal age categories between the years of 2011 and 2021.

Maternal age

Maternal age is an important risk factor for both obstetric and perinatal outcomes. Adverse outcomes are more common in younger and older mothers. Women in Australia are continuing to give birth later in life:

- The average age of women who gave birth was 31.1 in 2021 compared with 30.0 in 2011.

- The proportion of women giving birth aged 35 and over remained relatively stable from 23% in 2011 to 26% in 2021, while the proportion aged under 25 decreased from 18% to 11% (Figure 1).

Smoking status

Smoking during pregnancy is the most common preventable risk factor for pregnancy complications and is associated with poorer perinatal outcomes, including low birthweight, being small for gestational age, pre-term birth and perinatal death. Women who stop smoking during pregnancy can reduce the risk of adverse outcomes for themselves and their babies. Support to stop smoking is widely available through antenatal clinics.

Less than 1 in 10 (8.7%) mothers who gave birth in 2021 smoked at some time during their pregnancy, a decrease from 13% in 2011 (Figure 1). Of mothers who were smoking at the start of their pregnancy, around 1 in 4 (24%) quit smoking during the pregnancy.

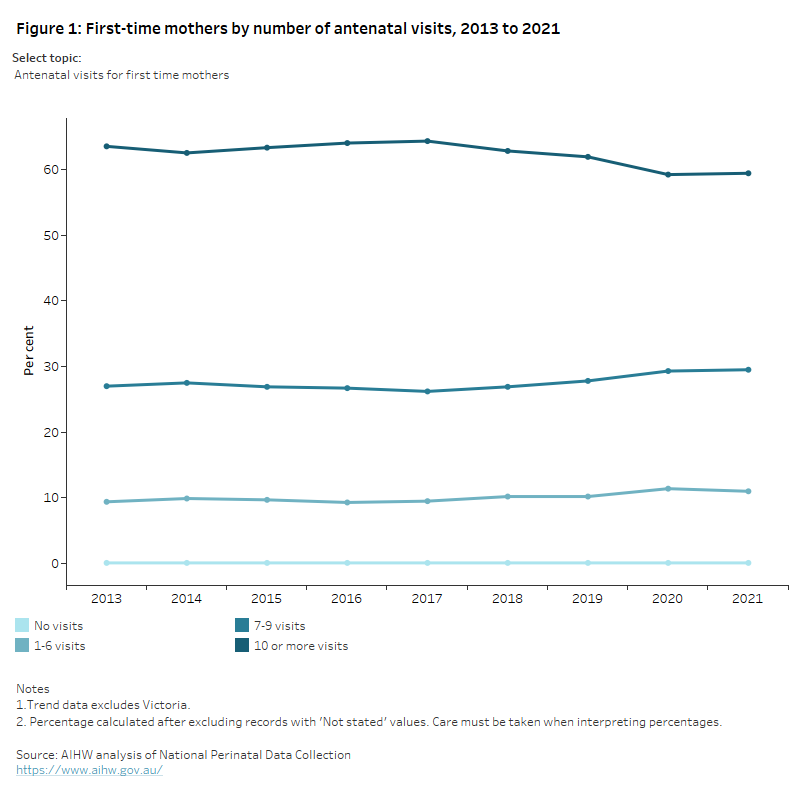

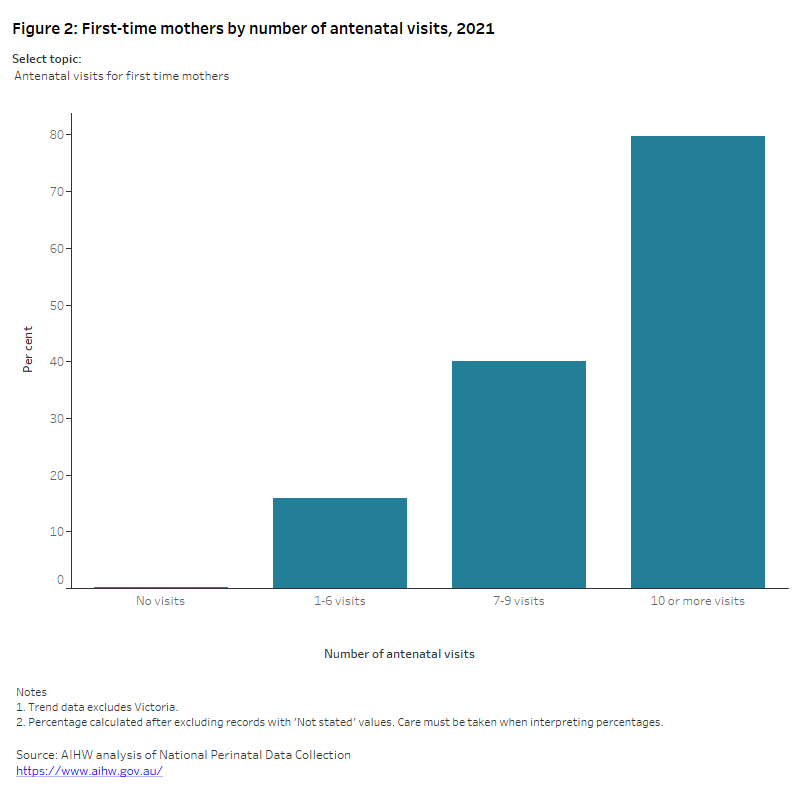

Antenatal care

Antenatal care is a planned visit between a pregnant woman and a midwife or doctor to assess and improve the wellbeing of the mother and baby throughout the pregnancy. Routine antenatal care, beginning in the first trimester (before 14 weeks gestational age), is known to contribute to better maternal health in pregnancy, fewer interventions in late pregnancy, and positive child health outcomes (AHMAC 2011; WHO RHR 2015).

Australian Pregnancy Care Guidelines

The Australian Pregnancy Care Guidelines recommend that the first antenatal visit occur within the first 10 weeks of pregnancy and that first-time mothers with an uncomplicated pregnancy have 10 antenatal visits during pregnancy (7 visits for subsequent uncomplicated pregnancies) (Department of Health 2021a). See the Australian Pregnancy Care Guidelines for more information.

Looking at the number of antenatal visits by mothers who gave birth at 32 weeks or more gestation in 2021:

- almost all mothers (99.8%) received antenatal care during pregnancy.

- 60% of mothers received antenatal care within the first 10 weeks of pregnancy.

Method of birth

In 2021, 62% of mothers (192,392) had a vaginal birth and 38% (118,887) had a caesarean section (Figure 2).

Half (50%) of all births were non-instrumental vaginal births. When instrumental births were required, vacuum extraction was more common than forceps (7.2% and 4.8% of all births, respectively) (Figure 2).

Since 2011, the rate of non-instrumental vaginal births decreased (from 56% in 2011 to 50% in 2021) whereas the caesarean section rate increased (from 32% in 2011 to 38% in 2021) (Figure 1). The rate of vaginal birth with instruments was relatively stable over this time, between 12% and 13%. These trends remain when changes in maternal age over time are considered.

Figure 2: Health factors of mothers, 2021

The chart shows the proportion of mothers in 2021 by maternal age categories.

Babies

Gestational age

Gestational age is the duration of pregnancy in completed weeks. Gestational age is reported in 3 categories: pre‑term (less than 37 weeks gestation), term (37 to 41 weeks) and post-term (42 weeks and over). The gestational age of a baby has important implications for their health, with poorer outcomes generally reported for those born early. Pre‑term birth is associated with a higher risk of adverse neonatal outcomes.

In 2021:

- the median gestational age for all babies was 39 weeks

- 91% of all babies born were born at term (Figure 3).

Birthweight

Birthweight is a key indicator of infant health and a principal determinant of a baby’s chance of survival and good health. A birthweight below 2,500 grams is considered low and is a known risk factor for neurological and physical disabilities. A baby may be small due to being born early (pre-term) or be small for gestational age, for example, due to fetal growth restriction within the uterus.

In 2021, 6.3% of babies born in Australia had low birthweight (Figure 3), and there has been little change since 2011. Birthweight and gestational age are closely related – low birthweight babies made up 56% of babies who were pre‑term compared with only 2.2% of babies born at term.

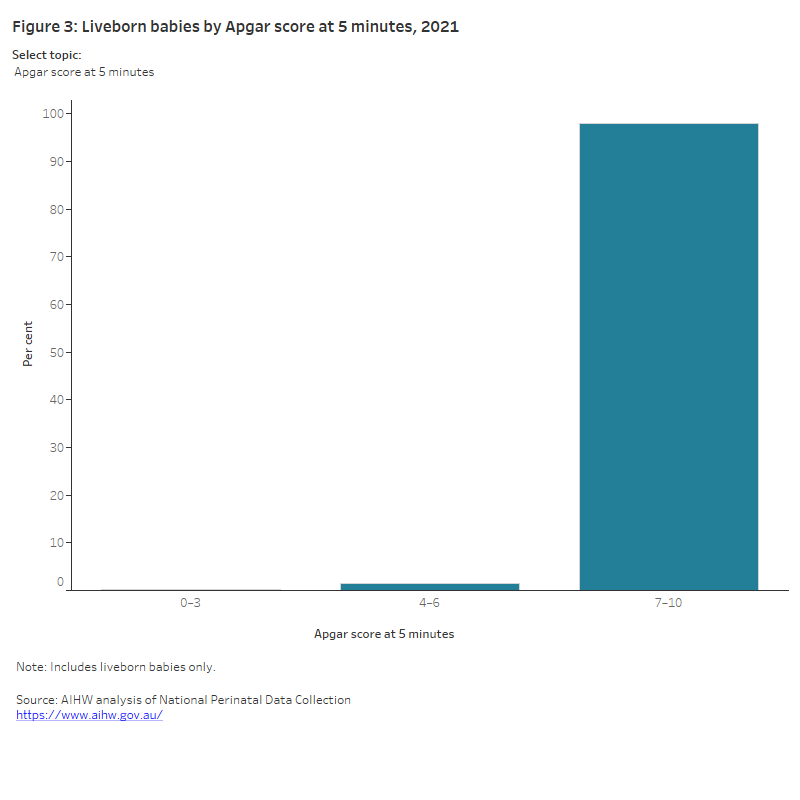

Apgar score at 5 minutes

Apgar scores are clinical indicators that determine a baby’s condition shortly after birth. These scores are measured on a 10-point scale for several characteristics. An Apgar score of 7 or more at 5 minutes after birth indicates the baby is adapting well post-birth.

The vast majority (98%) of liveborn babies in 2021 had an Apgar score of 7 or more at 5 minutes after birth (Figure 3). This rate has remained steady since 2011.

Resuscitation

Resuscitation is undertaken to establish independent breathing and heartbeat or to treat depressed respiratory effort and to correct metabolic disturbances. Resuscitation methods range from less intrusive methods like suction or oxygen therapy to more intrusive methods, such as external cardiac massage and ventilation. More than one type of resuscitation method can be recorded.

In 2021, 79 per 100 liveborn babies did not require resuscitation, however where resuscitation was required, continuous positive airway ventilation (CPAP) was reported as the most used method nationally and external cardiac compressions as the least common method.

Babies who required resuscitation were also more likely to have an Apgar score of less than 7, be of low birthweight, be born pre-term, and be born as part of a multiple birth.

Figure 3: Baby outcomes, 2021

The chart shows showing the proportion of live born babies in 2020 by Apgar score at 5 minutes after birth. The number of babies whose Apgar score was between 0 and 3 was 0.3%, the number of babies whose Apgar score was between 4 and 6 was 1.5% and the number of babies whose Apgar score was between 7–10 was 97.9%.

Perinatal deaths

A stillbirth is the death of a baby before birth, at a gestational age of 20 weeks or more, or a birthweight of 400 grams or more. A neonatal death is the death of a liveborn baby within 28 days of birth. Perinatal deaths include both stillbirth and neonatal deaths.

In 2021, there were 9.6 perinatal deaths for every 1,000 births, a total of 3,016 perinatal deaths. This included:

- 2,278 stillbirths, a rate of 7.2 deaths per 1,000 births

- 738 neonatal deaths, a rate of 2.4 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Between 2011 and 2021 the stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates have remained largely unchanged at between 7 and 8 in 1,000 births and between 2 and 3 in 1,000 live births, respectively. Congenital anomaly was the most common cause of perinatal death.

For more information see Perinatal deaths.

Maternal deaths

Maternal death is the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and outcome of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes.

Between 2012 and 2021, the maternal mortality ratio in Australia was relatively stable, ranging from between 5.2 to 8.4 per 100,000 women giving birth.

The most frequent causes of maternal death reported in Australia between 2012 and 2021 were cardiovascular disease and sepsis.

For more information see Maternal deaths.

Congenital anomalies

Congenital anomalies encompass a wide range of atypical bodily structures or functions that are present at or before birth. They are a cause of child death and disability, and a major cause of perinatal death.

In 2017, over 8,400 (3%) babies were born with a congenital anomaly, or around 23 babies born each day. Circulatory system anomalies (these are anomalies of the heart and major blood vessels) were the most common type of anomaly, 33% of babies with any anomaly having a circulatory system anomaly. Most (90%) babies with an anomaly survived their first year.

Congenital anomaly rates were higher in:

- babies born pre-term (before 37 weeks’ gestation), at a rate of 107 per 1,000 births

- babies born with low birthweight (less than 2,500 grams), at a rate of 123 per 1,000 births

- babies that were small for gestational age (that is with a birthweight below the 10th percentile for their gestational age and sex), at a rate of 44 per 1,000 births.

For more information see Congenital anomalies in Australia.

Maternity models of care

A maternity model of care describes how a group of women are cared for during pregnancy, birth, and the postnatal period.

In 2023, around 1,000 maternity models of care were reported across 251 maternity services in Australia, and these can be grouped into 11 different model categories. Amongst them:

- The most common model category is public hospital maternity care (41% of models), followed by shared care (15% of models), midwifery group practice caseload care (14% of models) and private obstetrician specialist care (11% of models).

- Just under one-third of models (29%) have continuity of carer through the whole maternity period, meaning a single, named carer provides or coordinates care for the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal periods; around one-third (35%) of models have continuity of carer for part of the maternity period (for example the antenatal period only or the antenatal and postnatal periods), and 36% of models have no continuity of carer in any stage of the maternity period.

- Around 63% of models target specific groups of women who share a common characteristic or set of characteristics, and 37% do not target any group of women. The broad target groups of low risk or normal pregnancy, and all excluding high risk pregnancy, are reported in 19% and 11% of models respectively, while Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander identification is a target group in 11% of models.

For more information, see Maternity models of care in Australia and the companion report Maternity models of care infocus.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on the health of mothers and babies, see:

- Australia’s mothers and babies

- Stillbirths and neonatal deaths

- Maternal deaths

- National Core Maternity Indicators

- Older mothers in Australia

- Antenatal care during COVID-19

- Congenital anomalies

- Maternal models of care

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers and babies.

AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council) (2011) National Maternity Services Plan, Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government, accessed 10 August 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021) Australia's mothers and babies, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 10 August 2023.

Department of Health (2021a) Clinical practice guidelines: pregnancy care, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 10 August 2023.

Department of Health (2021b) COVID-19 temporary MBS telehealth services, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 15 August 2023.

RANZCOG (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) (2021) A message for pregnant women and their families, RANZCOG, accessed 12 August 2023.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) (2022) Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in pregnancy. Information for healthcare professionals, RCOG website, accessed 10 August 2023.

WHO RHR (World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research) (2015) WHO statement on caesarean section rates, WHO website, accessed 13 August 2023.