Risk factors

Risk factors

Rates of health risk factors, such as smoking and obesity, are higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (AIHW 2020a).

Smoking during pregnancy

Smoking during pregnancy is a preventable risk factor for pregnancy complications and is associated with poorer perinatal outcomes, including low birthweight, being small for gestational age, pre-term birth and perinatal death (AIHW 2022a).

Smoking is associated with socioeconomic disadvantage – with the prevalence of smoking increasing with levels of socioeconomic disadvantage (Bonevski and Baker 2012). Evidence suggests that action at both the system level and the individual level can reduce smoking rates (Bonevski and Baker 2012).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are more likely to smoke than non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2020a). The vast majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who smoke want to quit or wish they had never started smoking (Kennedy and Maddox 2022).

Some pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have reported difficulties with stopping smoking due to their social environment and daily stressors and a lack of culturally sensitive support and information (Passey et al. 2012; Tzelepis et al. 2017).

This report shows that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth and smoked at any time during their pregnancy were more likely than those who did not smoke, to give birth to a baby who was born pre-term, of low birthweight or small for gestational age (for more information on the effect of maternal smoking see Baby outcomes).

The National Perinatal Data Collection collects information on self-reported smoking status at 3 time points – at any time during pregnancy, in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy and after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

In 2020:

- 43% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth reported having smoked at any time during their pregnancy

- 42% reported having smoked in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy

- 38% reported having smoked after 20 weeks of pregnancy

In comparison, among non-Indigenous females who gave birth 7.5% smoked at any time during pregnancy, 7.1% smoked in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy and 5.4% smoked after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

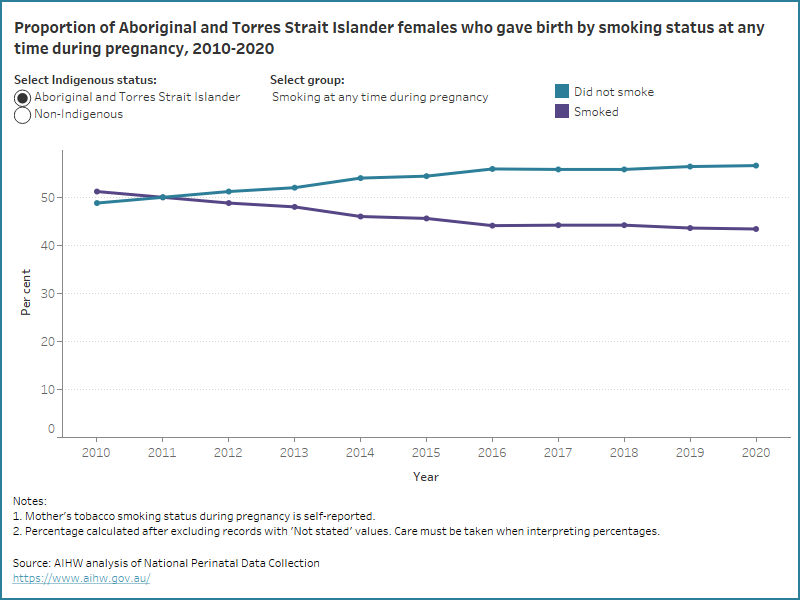

Over time, the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who smoked at any time during pregnancy has decreased (from 51% in 2010 to 43% in 2020), as has the proportion who smoked in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy (from 50% in 2011 to 42% in 2020) and after 20 weeks of pregnancy (from 45% in 2011 to 38% in 2020).

Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who were participants in the community-led Which Way? Smoking Cessation Study reported that they would prefer smoking cessation support programs that were delivered in groups, face to face at an Aboriginal health service and by Aboriginal Health Workers (Kennedy and Maddox 2022). One example of a smoking cessation program which uses community level population health promotion activities is the Tackling Indigenous Smoking program (TISRIC 2020).

Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers may smoke before knowing they are pregnant and stop once they find out they are pregnant. In 2020, 13% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who reported having smoked in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy did not continue to smoke after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

The data visualisation below shows the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous females who gave birth by smoking status at any time during pregnancy from 2010, and smoking status in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy or after 20 weeks of pregnancy from 2011.

Figure 1: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous females who gave birth by smoking status from 2010 to 2020

Line graph of smoking status by Indigenous status. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who did not smoke increased.

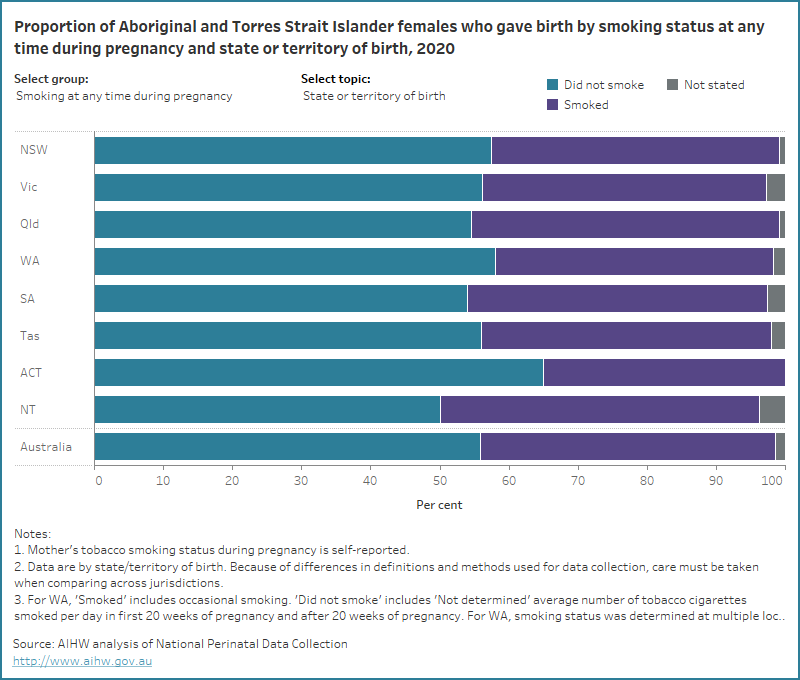

In 2020, the proportions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who smoked at any time during pregnancy were highest for those who:

- lived in the most disadvantaged areas (49%, compared with 26% of those who lived in the least disadvantaged areas)

- lived in Very remote areas (53%, compared with 37% of those who lived in Major cities)

- were aged under 20 years (45%, compared with 41% of those in the most common maternal age group (aged 25-29 years))

- had a parity of 4 or more (59%, compared with 36% of first-time mothers)

The data visualisation below presents data on the smoking status at any time during pregnancy, in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy and after 20 weeks of pregnancy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth, by selected maternal characteristics for 2020.

Figure 2: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth by smoking status and selected topic for 2020

Bar chart for smoking status by selected topics. 56% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers did not smoke at any time during pregnancy.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who lived in some geographical locations were more likely to smoke at any time during pregnancy. Explore the map below to view data on the number and proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who smoked at any time during pregnancy, by IREG and PHN for 2020 and SA3 for 2017-2020.

Figure 3: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth and smoked at any time during pregnancy by various geographies

Map of proportions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who smoked at any time during pregnancy across Australia grouped by various geographies.

For related information see:

- the Regional Insights for Indigenous Communities section on Smoking status.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework indicator 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy.

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy

Alcohol consumption in pregnancy can lead to poorer perinatal outcomes including low birthweight, being small for gestational age, pre-term birth and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (NHMRC 2020). Therefore, National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines recommend that to prevent harm to their unborn child, women who are pregnant should avoid consuming alcohol (NHMRC 2020).

A survey of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers’ drinking choices found that those who abstained from consuming alcohol during pregnancy reported doing so as they were aware of the responsibility to their developing baby and were supported by family and community (Gibson et al. 2020). Building on these strengths in public health messaging and ensuring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers have access to culturally safe and woman-centred antenatal care is key to reducing alcohol-related harm (Gibson et al. 2020).

In addition to antenatal care, the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet Alcohol and Other Drugs Knowledge Centre lists many programs aimed at supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, and their families, to address alcohol consumption.

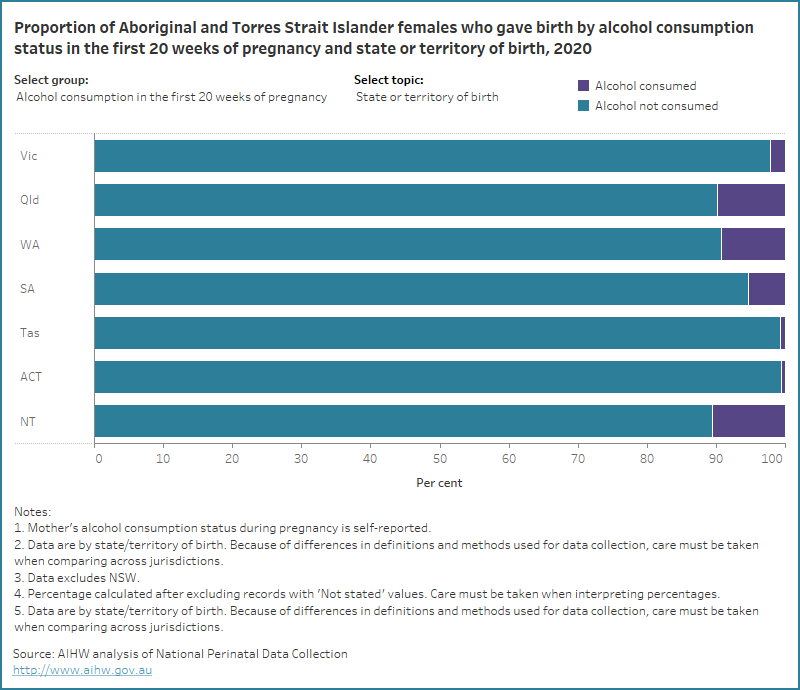

In 2020, 8.2% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth consumed alcohol in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy and 3.6% consumed alcohol after 20 weeks of pregnancy (compared with 2.4% and 0.6%, respectively, of non-Indigenous females.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers were more likely to consume alcohol in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy if they:

- lived in the most disadvantaged areas (9.8%)

- lived in Very remote areas (14%)

- were aged 30-34 years (11%)

- had a parity of 4 or more (12%).

Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers may consume alcohol before knowing they are pregnant and stop once they find out they are pregnant. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers showed a decline in alcohol consumption after 20 weeks of pregnancy with:

- 4.6% of those who lived in the most disadvantaged areas consuming alcohol

- 7.4% of those who lived in Very remote areas consuming alcohol

- 5.6% of those aged 30-34 years consuming alcohol

- 6.4% of those with a parity of 4 or more consuming alcohol.

The data visualisation below presents data on the alcohol consumption status in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy and after 20 weeks of pregnancy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth, by selected maternal characteristics for 2020.

Figure 4: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth by alcohol consumption status and selected topic for 2020

Bar chart for alcohol consumption by selected topics. Most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers did not consume alcohol in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy.

Maternal body mass index

Obesity in pregnancy puts mothers at increased risk of conditions such as pre-eclampsia, and their babies have higher rates of congenital anomaly, stillbirth and neonatal death (AIHW 2022a). Mothers who are underweight may have underlying maternal health conditions – leading to increased risk of complications – and babies of mothers who are underweight are more likely to be born preterm and of low birthweight (Burnie et al. 2022).

Box 1: Body mass index

BMI is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by the square of their height in metres. BMI does not necessarily reflect body fat distribution or describe the same degree of fatness in different individuals. At a population level, however, it is a practical and useful measure to identify overweight and obesity (AIHW 2020b).

A BMI of:

- less than 18.5 is classified as underweight

- between 18.5 and less than 25 is classified as normal weight

- between 25 and less than 30 is classified as overweight

- 30 or more is classified as obese

In the NPDC, BMI refers to pre-pregnancy BMI. However, source data and methods used for data collection are not uniform nationally. For example, BMI can be calculated based on self-reported height and weight or on those measured at their first antenatal visit.

Factors that contribute to living with overweight or obesity include a lack of physical activity and poor nutrition. According to the 2018-2019 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health survey, 90% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females reported that they did not meet the physical activity guidelines and 96% reported that they did not meet daily fruit and vegetable consumption guidelines (age-standardised).

In comparison, 86% of non-Indigenous females did not meet the physical activity guidelines and 93% did not meet daily fruit and vegetable consumption guidelines (age-standardised) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2019). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples may face challenges in accessing affordable and healthy food, potentially leading to obesity and/or malnutrition and increasing the risk of nutrition-related diseases such as type 2 diabetes (AIHW 2022b; AIHW 2020a).

This report shows that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who gave birth and were obese, were more likely than those who had a healthy weight to give birth to a baby with a high birthweight or who were large for gestational age.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who were underweight were more likely than those with a healthy weight, to give birth to a baby who was pre-term, of low birthweight or small for gestational age (for more information on the effect of maternal BMI see Baby outcomes).

In 2020, 35% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth had a healthy weight, 6.2% were underweight, 25% were overweight and 34% were obese (compared with 47%, 2.9%, 28%, and 22%, respectively, of non-Indigenous females).

Over time, the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who were living with obesity has increased (from 29% in 2012 to 34% in 2020) and the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who were overweight and underweight remained stable (between 24% and 26% and 6.4% and 7.7%, respectively).

The data visualisation below shows the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous females who gave birth by BMI group, from 2012.

Figure 5: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous females who gave birth by body mass index from 2012 to 2020

Line graph of maternal body mass index and Indigenous status. The rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers living with obesity has increased

The maternal age group with the highest proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who were obese were those aged 40 years and over (43%) and the lowest proportion were those aged under 20 years (14%).

The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who were underweight was highest for those who lived in Very remote areas (8.2%), were aged under 20 (13%) and first-time mothers (7.8%).

The data visualisation below presents data on BMI group for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth, by selected maternal characteristics for 2020.

Figure 6: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth by body mass index and selected topic for 2020

Bar chart for BMI group by selected topics. 35% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers had a normal weight.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who lived in some geographical locations were more likely to be living with obesity. Explore the map below to view data on the number and proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who were living with obesity, by IREG and PHN for 2020 and SA3 for 2017-2020.

Figure 7: Proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females who gave birth and were living with obesity by various geographies

Map of proportions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who were living with obesity across Australia grouped by various geographies.

References

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2019) Microdata: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018-19, AIHW analysis of microdata ,accessed 10 October 2022.

AIATSIS (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies) (2022) Welcome to Country, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies website, accessed 10 October 2022.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2022a) Australia’s mothers and babies, Cat. no. PER 101. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2022b) 2.19 Dietary Behaviour Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework website, accessed 17 October, 2022.

AIHW (2020a) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2020 summary report. Cat. no. IHPF 2. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2020b) Overweight and obesity: an interactive insight, Cat. no. PHE 251, AIHW, accessed 10 October 2021.

Bonevski B and Baker A (2012). ‘Tobacco smoking as a social justice issue: Advances in research’, Drug and Alcohol Review 31(5), doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00478.x.

Burnie R, Golob E and Clarke S (2022) ‘Pregnancy in underweight women: implications, management and outcomes’ The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 24(1), doi:10.1111/tog.12792.

Gibson S, Nagle C, Paul J, McCarthy L and Muggli E (2020). ‘Influences on drinking choices among Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnant women in Australia: A qualitative study’, PLOS ONE, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224719.

Kennedy M and Maddox R (2022) ‘Ngaaminya (find, be able to see): summary of key findings from the Which Way? project’, MJA, doi: 10.5694/mja2.51622.

NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) (2020) 'Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol', NHMCR, Australian Government, accessed 13 October 2021.

Passey ME, D’Este CA, Stirling JM and Sanson-Fisher RW (2012). ‘Factors associated with antenatal smoking among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in two jurisdictions’, Drug and Alcohol Review 31(5), doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00448.x.

TISRIC (Tackling Indigenous Smoking Resource and Information Centre) (2020) Pregnant women and families, Tackling Indigenous Smoking website, accessed 19 October 2022.

Tzelepis F, Daly J, Dowe S, Bourke A, Gillham K and Freund M (2017). ‘Supporting Aboriginal Women to Quit Smoking: Antenatal and Postnatal Care Providers’ Confidence, Attitudes, and Practices’, Nicotine & Tobacco Research 19(5), doi:10.1093/ntr/ntw286.