Housing and living arrangements

Housing plays a critical role in the health and wellbeing of older Australians (SCRGSP 2020). It serves the basic human need for physical shelter and contributes to physical, psychological, health and emotional security. Home ownership in particular, provides older people with security of housing tenure and long-term social and economic benefits (AIHW 2019). It can be a key determinant of wealth and financial security in retirement (PC 2015).

Many older Australians prefer to age in place, meaning they wish to stay in their local home or community (PC 2015). However, their capacity to do so can be influenced by:

- the appropriateness and quality of their home (for example, size, layout)

- their ability to modify their home to suit their functional requirements

- the cost and availability of suitable housing

- their need for formal care and assistance

- their proximity to services and social support.

Throughout this page, ‘older people’ refers to people aged 65 and over. Where this definition does not apply, the age group in focus is specified. The ‘Older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’ feature article defines older people as aged 50 and over. This definition does not apply to this page, with Indigenous Australians aged 50–64 not included in the information presented.

Housing tenure

Home ownership

Older Australians have traditionally had high rates of home ownership. This has often provided a key financial asset on retirement. In more recent years, the rate of home ownership among older people has decreased, consistent with decreases in home ownership seen in the broader population (people aged 15 and over). In 2017–18, three-quarters (74%) of households with a reference person aged 65 or over were owners without a mortgage, compared with around 8 in 10 (79%) in in 2003–04 (ABS 2006, 2019).

Home ownership patterns for older people vary according to their living arrangements. In 2017–18, 9 in 10 (92%) older couple households owned a home (92%), with around 8 in 10 (81%) owning their home without a mortgage and 1 in 10 (11%) with a mortgage. Around 3 in 4 older lone person households (75%) owned a home, with around 7 in 10 (69%) owning without a mortgage and 1 in 17 (6%) owning their home with a mortgage (ABS 2019).

In 2017–18, 2.3% of recent first home buyers were aged 65 and over (age of household reference person), with a further 21% being changeover buyers - that is, they had previously owned a home (ABS 2019).

Renting in the private market

Often older Australians rent out of necessity rather than choice (PC 2015). Renting at an older age can be associated with the risk of poverty and adverse impacts on health and wellbeing (AHURI 2018). Older people renting can be disproportionately affected by insecure tenures and as such, be at an increased risk of homelessness (AIHW 2019). Furthermore, older households who rent can be more likely to move than those owning their homes outright (AIHW 2020).

In 2017–18, 1 in 7 (14%) households with a reference person aged 65 or over were renters. Most rented from a private landlord (64%) and around 1 in 4 (24%) rented from a state or territory housing authority.

In 2017–18 older lone persons were more likely to rent (22%) than older people in couple only households (6.2%). Of older lone persons renting:

- 13% rented from private landlords

- 6.4% from state or territory housing authorities.

Of older people in couple only households renting:

- 4.8% rented from private landlords

- 1.3% from state or territory housing authorities (ABS 2019).

For further information on housing tenure of older Australians see Older clients on Specialist homelessness services and Housing occupancy and costs.

Social housing

Older people having difficulty meeting the costs of housing can be supported by housing assistance programs such as financial assistance and social housing (such as public and community housing). Whether it is managed by state and territory governments or community-based organisations, social housing can play a critical role in reducing financial and housing stress and improving physical and mental wellbeing.

During 2019–20, older people (aged 65 and over) represented:

- 1 in 5 public housing household members (21%, 121,900)

- 1 in 5 community housing household members (19%, 34,300) (AIHW 2021).

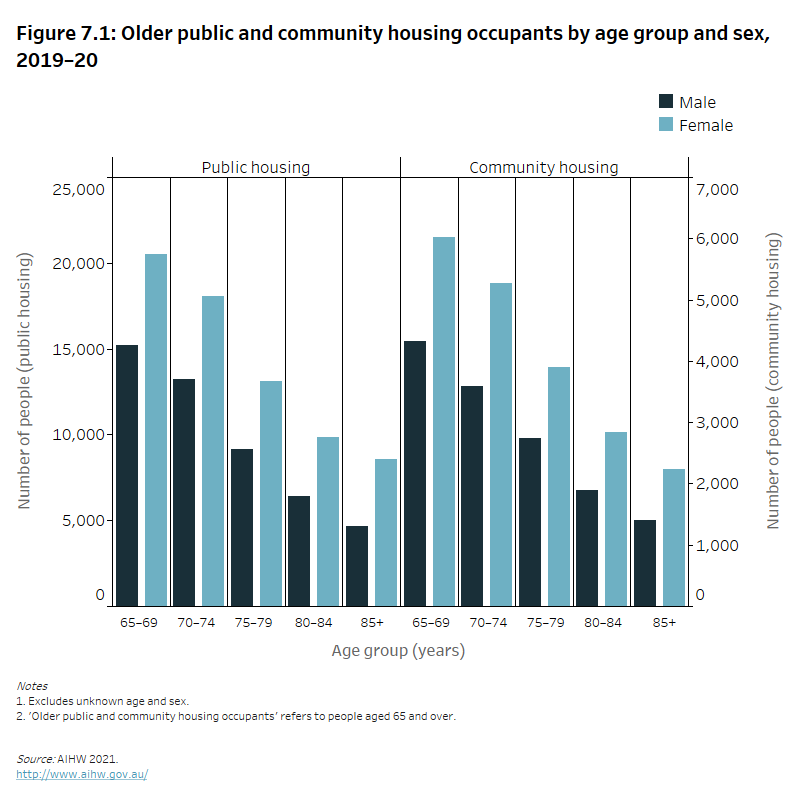

Women make up the majority of all occupants, and older occupants, in public and community housing. During 2019–20, females accounted for 59% of public housing and 59% of community housing occupants aged 65 and over (AIHW 2021) (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1: Older public and community housing occupants by age group and sex, 2019–20

The column graph shows that in 2019–20 the number of older Australians in public and community housing was smaller for those who were older. In each age group, the number of females using public and community housing was larger than the number of males.

Social housing is generally allocated according to groups deemed to have priority needs. Older people aged 75 and over are one special needs group for housing allocation (AIHW 2021). In 2019–20, of the 10,300 newly allocated public housing households to people with special needs, 6.0% (around 600 households) had a main tenant aged 75 or over (AIHW 2021). More broadly, 12% of newly allocated public housing went to main tenants aged 65 and over.

Homelessness and insecure housing

The pathways into homelessness for older Australians are varied. Some may have had a conventional housing history earlier in life, but have experienced financial trouble, divorce or other disruptions later in life, that have placed them at risk of homelessness. Others may have experienced homelessness or insecure housing throughout life, sometimes with repeated attempts to achieve housing stability (AIHW 2020; Petersen et al. 2014).

For people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness (generally due to living in insecure housing), ‘older people’ can refer to people who are aged under 65. The disadvantages associated with homelessness or insecure housing are many, and people who are homeless or living in insecure housing may be experiencing poor physical and mental health or substance misuse. They can also experience earlier onset of health problems usually associated with older age. To capture elements of this, people aged 55 and over are considered ‘older people’ in this context.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics defines homelessness as a situation where someone does not have suitable accommodation, and their current living arrangement:

- is in a dwelling that is inadequate (is unfit for human habitation and lacks basic facilities such as kitchen and bathroom facilities)

- has no tenure, or if their initial tenure is short and not extendable

- does not allow them to have control of, and access to space for social relations (including personal or household living space, ability to maintain privacy and exclusive access to kitchen and bathroom facilities).

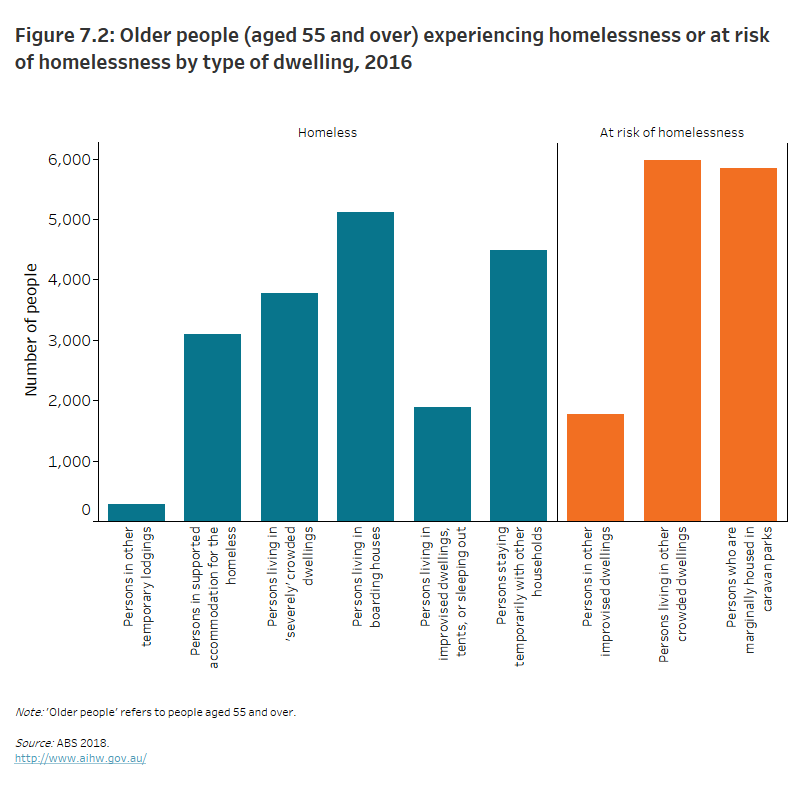

On Census night in 2016, 18,600 people aged 55 and over were homeless (representing 16% of all homeless people in Australia). There were a further 13,600 older people living in marginal housing (such as caravan parks and crowded or improvised dwellings) who were potentially at risk of homelessness.

The majority of older homeless people were aged 55–64 (57%), with those aged 65–74 accounting for 30% and those aged 75 and over, 12%.The patterns were broadly similar for those at risk of homelessness, with a small shift towards older age (the percentages were 51%, 33% and 17%, respectively) (ABS 2018).

Most commonly, older people experiencing homelessness were living in boarding houses (27%) or staying temporarily with other households (24%) (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2: Older people (aged 55 and over) experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness by type of dwelling, 2016

The column graph shows that in 2016 older Australians experiencing homelessness were most commonly living in boarding houses or staying temporarily with other households (28% and 24% respectively). Older Australians at risk of homelessness were most commonly living in other crowded dwellings or marginally housed in caravan parks (44% and 43% respectively).

The overall rate of older people (aged 55 and over) experiencing homelessness increased from 25.8 to 29.0 per 10,000 people between 2006 and 2016 (ABS 2018). Homelessness is a growing problem for older Australians, and may continue to increase over time due to the increase in the ageing population and the decrease in the rate of home ownership among older people.

In addition, particular groups of older people may be at a higher risk of homelessness, such as veterans, Indigenous people and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (Parliament of Australia 2020). For example, around 8% of older homeless people were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people (ABS 2018). Also, although older women do not account for the majority of homeless people, they represent a rapidly growing demographic in the homeless population - increasing by 31% between 2011 and 2016 (ABS 2018). Factors such as domestic violence, relationship breakdown, financial difficulty and limited superannuation can put people at risk of homelessness (ABS 2018).

Older people sleeping out or staying in supported accommodation on Census night

While definitions of homelessness and being at risk of homelessness cover broader territory, in layman terms, ‘homeless’ is commonly thought of as living on the streets or accessing homelessness shelters. The Census also provides a snapshot of this population. On Census night 2016, there were almost 1,900 people aged 55 and over sleeping out or staying in a tent or other improvised dwelling and 3,100 people aged 55 and over staying in supported accommodation for the homeless (ABS 2018).

Some people at risk of, or experiencing homelessness, may seek help from specialist homelessness services (SHS). In 2019–20, there were over 24,400 older clients (55 and over) who received services from SHS agencies. Of these older clients:

- around 60% were living alone

- 55% were returning clients

- 30% were currently experiencing a mental health issue

- 15% were Indigenous

- 5.0% had a disability (AIHW 2020).

At the start of support, older clients are much more likely to be at risk of homelessness (66%) than experiencing homelessness (35%). This profile is different to the total SHS client group where 43% of clients are experiencing homelessness and 57% are at risk of homelessness (AIHW 2020).

The main reasons older people who were experiencing homelessness sought assistance were due to a housing crisis (such as eviction) (24%) or inadequate dwelling conditions (23%). At the same time, the main reasons older people who were a risk of homelessness sought assistance were due to financial difficulties (20%) and family and domestic violence (18%).

More information is reported in the Specialist homelessness services annual report, which summarises data from the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection, and in the Older clients of specialist homelessness services report.

Types of dwellings

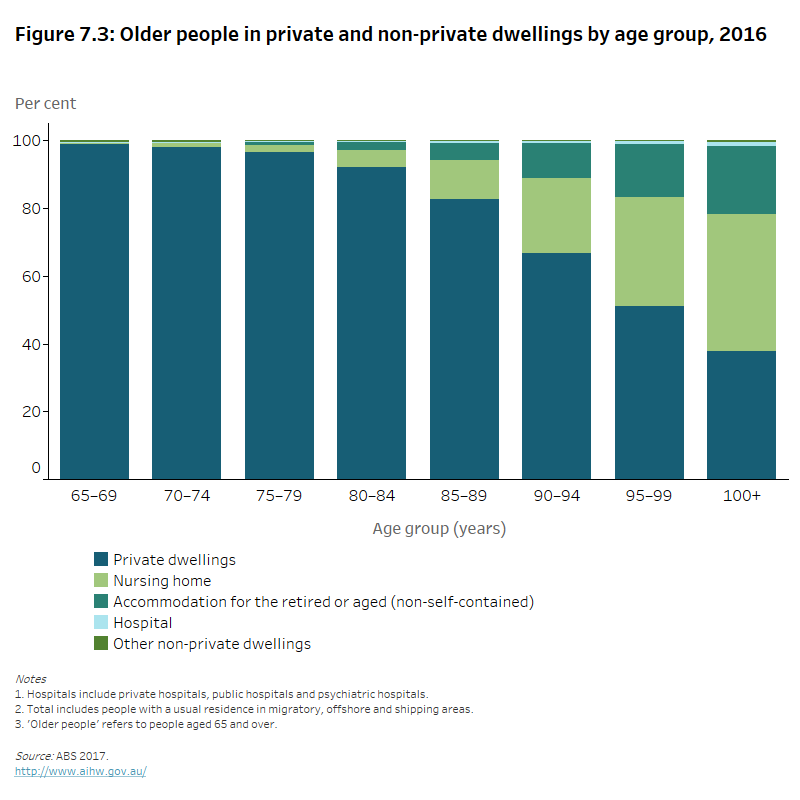

According to the 2016 Census, most older Australians lived in private dwellings:

- 99% of people aged 65–74 years

- 75% of those aged 85 and over (see Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3: Older people in private and non-private dwellings by age group and sex, 2016

The stacked column graph shows that in 2016 the majority of older Australians occupied private dwellings. However, the proportion of older Australians occupying private dwellings decreased as age increased (99% of people aged 65–69 lived in private dwellings compared to 38% of those aged 100 and over).

There were differences between men and women with women aged 75 and over less likely than men to live in a private dwelling. This difference was most noticeable for the 85 and over group, where 71% of women and 82% of men lived in private dwellings.

In contrast, a small percentage of older people (5.7%) lived in a non-private dwelling which often provide communal or short-term accommodation. In 2016, of the older people who lived in non-private dwellings, most (91%) were in cared accommodation (nursing homes or accommodation for the aged with common living and eating facilities). The percentage of all older people living in cared accommodation increased sharply with age from 1.0% of people aged 65–74 to 24% of those aged 85 and over. For people aged 85 and over, women were more likely than men to live in cared accommodation (28% compared with 17%, respectively) (ABS 2017).

For information about older people living in aged care settings or receiving care in their home, see Aged care.

Dwelling structure

In 2017–18, for couple-only households where the reference person was 65 and over:

- 89% were living in a separate house

- 7.3% in a semi-detached house or townhouse

- 3.4% in a flat or apartment.

For older people in lone-person households:

- 67% were living in a separate house

- 19% in a semi-detached house or townhouse

- 14% in a flat or apartment (ABS 2019).

Living arrangements

In 2016, more than half (58%) of all older people (aged 65 and over) lived with a spouse or partner in a private dwelling, with a further 25% living alone.

Older people who lived with a spouse or partner included those who lived:

- with no children in the dwelling (48% of all older people)

- with children (7.7%)

- in a multi-family household (2.6%).

Older people aged 65–74 were most likely to live with a spouse or partner (68%), and older people aged 85 and over were more likely to live alone (35%) than other age groups.

The likelihood of a person living alone increases with age, with a sharper increase for older women than older men. Nearly 1 in 3 (31%) older women lived in a lone person household compared with almost 1 in 5 older men (18%). The difference was greatest for the 85 years and over group (41% of women compared with 25% of men) (ABS 2017).

Housing preferences

Around 1 in 3 (35%) older Australians (aged 55 and over) surveyed in an Australian Housing Aspirations survey wanted to live in a home in the middle to outer suburbs of capital cities. This preference increased with age. More than 2 in 3 (69%) preferred a detached dwelling with 3 bedrooms (50%) the most common choice. Most older Australians surveyed did not want to be in the private rental market with 4 in 5 (80%) choosing home ownership as the preferred tenure. Results indicated that many older people currently renting had previously been in home ownership, moving into renting due to relationship breakdown or financial hardship (James et al 2019).

Housing suitability

One measure of housing suitability is based on considering the appropriate number of bedrooms in a dwelling in relation to the household size and composition (for example, couple only, or family with children).

Results from the 2016 Census showed that 76% of older people who were a spouse or partner and 65% of older people in a lone-person household lived in a dwelling with 2 or more spare bedrooms (ABS 2018).

Living in a dwelling with more bedrooms than the number of people who usually live there may reflect a choice or that some people may be discouraged from downsizing due to financial or other disincentives.

Accessibility is another key aspect of housing suitability. The suitability of a dwelling can depend on its physical characteristics in relation to the needs of an older person (such as mobility limitations and restrictions). The arrangement, design and facilities within the home are of great importance with increasing age and frailty. For more information, see ‘Disability’ in Health – status and functioning.

Where do I find more information?

For more information on older Australia’s housing and living arrangements, see:

- Australian Human Rights Commission Older women’s risk of homelessness: background paper

- My Aged Care Support for people facing homelessness

For information about older people living in aged care settings or receiving care in their home, see Aged care. Information about government financial support for housing expenses can be found in Income and finances.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2006. Housing occupancy and costs 2003–04. ABS cat. no. 4130.055.001. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2020-21.

ABS 2017. Census of Population and Housing: reflecting Australia – stories from the Census, 2016. ABS cat. no. 2071.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2020-21.

ABS 2018. Census of Population and Housing: estimating homelessness, 2016. ABS cat. no. 2049.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2020-21.

ABS 2019. Housing occupancy and costs 2017–18. ABS cat. no. 4130.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2020-21.

AHURI (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute) 2018. Supporting older lower income tenants in the private rental sector. Melbourne: AHURI. Viewed 2020-21.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019. Older clients of specialist homelessness services. Cat. no. HOU 314. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2020-21.

AIHW 2020. Specialist homelessness services annual report 2019–20. Cat. no. HOU 322. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2020-21.

AIHW 2021. Housing Assistance in Australia 2020. Cat. no. HOU 325. Canberra: AIHW Viewed 2021.

James A, Rowley S, Stone W, Parkinson S, Spinney A and Reynolds M 2019. Older Australians and the housing aspirations gap. AHURI Final Report No. 317. Melbourne: AHURI. Viewed 2020-21.

Parliament of Australia 2020. Shelter in the storm – COVID-19 and homelessness. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs. Canberra: Parliament of Australia. Viewed 2020-21.

Petersen M, Parsell C, Phillips R and White G 2014. Preventing first time homelessness amongst older Australians. AHURI Final Report No. 222. Melbourne: AHURI. Viewed 2020-21.

PC (Productivity Commission) 2015. Housing decisions of older Australians: Commission Research Paper. Canberra: Productivity Commission. Viewed 2020-21.

SCRGSP (Steering Committee Report on Government Service Provision) 2020. Report on Government Services 2020, chapter 18: housing – interpretive material. Canberra: Productivity Commission. Viewed 2020-21.