Smoking

Smoking status

Smoking rates among the 1,011 prison entrants during the 2015 NPHDC were high, with 74% being current smokers and almost all of these (93%, or 69% of all entrants) being daily smokers. In comparison, 13% had never smoked and 9% were ex-smokers. This does represent a decrease since the 2012 NPHDC, when 84% of prison entrants were current smokers. However, at least some of this decrease may be due to recently introduced smoking bans in prisons. Prison entrants, on average, smoked their first full cigarette at 14.1 years. The youngest age at which they began smoking reported by several prisoners was 5, and the oldest was 40.

A slightly higher proportion of male (69%) than female (66%) entrants were daily smokers. The declines in smoking rates over the last 20 years experienced in the general community are not reflected in the prison entrant population, whose smoking rates remain high. The proportion of entrants being daily smokers declined with age from a high of 73% of entrants aged 18–24 years, to a low of 56% of those aged at least 45 years. In addition to being less likely to be daily smokers, prison entrants aged 45 or older were also almost twice as likely as those in the youngest age group to have never smoked (19% compared with 10%).

Indigenous (82%) prison entrants were more likely than non-Indigenous (72%) entrants to be a current smoker. Non-Indigenous entrants were three times as likely as Indigenous entrants to be ex-smokers (12% compared with 4%).

Comparisons with the general community

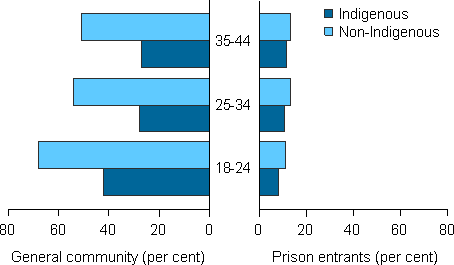

Smoking rates among people entering prison are much higher than in the general community (Table 1). Of prison entrants aged 18–44, around three-quarters (68–78%) are daily smokers, compared with around half (43–52%) of Indigenous Australians and 1 in 5 (16–19%) of non-Indigenous people of the same age in the general community.

Striking differences are also found when looking at ex-smokers and those that never smoked. In the general community, the proportion of people who say they have never smoked is highest among younger people, suggesting that over time, fewer young people in the general population are trying and taking up smoking. However, among prison entrants, the opposite is true (Figure 1). Similarly, with fewer people in the general community now taking up and then quitting smoking, the proportion of ex-smokers rises from around 13% of 18–24 year olds to 23–29% of 35–44 year olds. However, among prison entrants, the proportions of ex-smokers show no clear trends.

| Smoking status | Indigenous status | General community 18–24 |

General community 25–34 |

General community 35–44 |

Prison entrants 18–24 |

Prison entrants 25–34 |

Prison entrants 35–44 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | Indigenous | 43 | 52 | 48 | 74 | 78 | 68 |

| Non-Indigenous | 16 | 19 | 18 | 73 | 68 | 69 | |

| Current but not daily | Indigenous | 3 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 9 |

| Non-Indigenous | 3 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 7 | |

| Ex-smoker | Indigenous | 13 | 18 | 23 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Non-Indigenous | 14 | 24 | 29 | 10 | 13 | 8 | |

| Never smoked | Indigenous | 42 | 28 | 27 | 8 | 11 | 12 |

| Non-Indigenous | 68 | 54 | 51 | 11 | 13 | 13 |

Sources: Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Updated Results, 2012–13. ABS cat no. 4727.0.55.006. Canberra: ABS, Table 10.3; Entrants form 2015 NPHDC.

Figure 1: Prison entrants and general community, never smoked, by Indigenous status, 2015

Sources: Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Updated Results, 2012–13. ABS cat no. 4727.0.55.006. Canberra: ABS, Table 10.3; Entrants form 2015 NPHDC.

Smoking bans in prisons

Smoking bans are being implemented in prisons across Australia—in Northern Territory from July 2013, Queensland from May 2014, Tasmania from February 2015, Victoria from July 2015, New South Wales from August 2015. A trial is planned for South Australia in March 2016. The prison in Australian Capital Territory is not expected to be smoke-free before July 2016.

Of the 55 prisons from which dischargee data were received, 16 had total smoking bans in place at the time of the data collection. Dischargees in the data collection were almost evenly distributed between prisons with and without a smoking ban.

Changes to smoking habits while in prison

Table 2 compares the smoking status of dischargees in prisons with and without smoking bans. The results clearly show a reduction in smoking in prisons with a total smoking ban.

There are several possible reasons why prisoners in prisons with complete smoking bans may still report that they are current smokers. Firstly, there may be some who had been in prison for a very short time and still consider themselves to be smokers from their smoking status prior to prison. Secondly, there may be opportunities to smoke even in prisons with complete bans, such as at court appearances, or during work or other release times. Finally, smoking bans can be difficult to enforce.

| Smoking status | Prison bans smoking Number |

Prison bans smoking Per cent |

Prison allows smoking Number |

Prison allows smoking Per cent |

Total prison dischargees Number |

Total prison dischargees Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoker on entry | 161 | 72 | 159 | 75 | 320 | 73 |

| Current smoker | 40 | 18 | 157 | 74 | 197 | 45 |

| Smokes more now | 8 | 4 | 34 | 16 | 42 | 10 |

| Smokes less now | 125 | 56 | 46 | 22 | 171 | 39 |

| Total | 224 | 51 | 213 | 49 | 437 | 100 |

Notes

-

Excludes New South Wales, as data were not provided for dischargees.

-

Totals include prison dischargees whose smoking status was unknown.

-

Rows in each column will not sum to the total because individual dischargees may appear in more than one row.

Source: Discharge form, 2015 NPHDC.

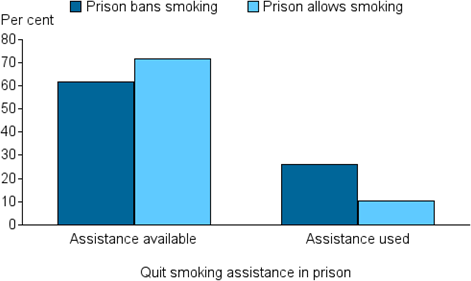

Most dischargees reported that smoking cessation assistance was available in their prison (Figure 2). Those in prisons allowing smoking were more likely (72%) than those in prisons with smoking bans (62%) to report that assistance was available. Those dischargees in prisons with smoking bans were also more likely to use available assistance to quit than those in prisons allowing smoking (26% compared with 10%).

Figure 2: Prison dischargees, use of quit smoking assistance in prison, 2015

Note: Excludes New South Wales, as data were not provided for dischargees.

Source: Dischargee form, NPHDC 2015.

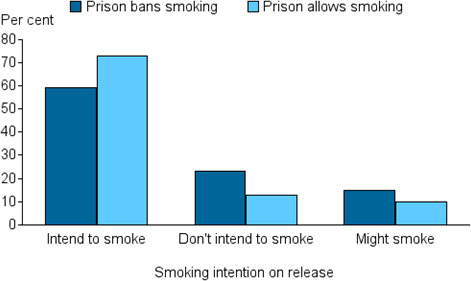

The reduction in smoking in prisons in which smoking is banned may flow through to the community. Of those who smoked on entry to prison, dischargees from prisons with smoking bans were less likely to intend to smoke after release than those from prisons in which smoking is allowed (59% and 73% respectively) (Figure 3). Almost one-quarter (23%) of dischargees (who smoked on entry to prison) from prisons with a ban said they do not intend to smoke upon release, compared with 13% of those from prisons allowing smoking. One-in-ten dischargees from prisons allowing smoking were undecided, as were 15% of those being released from prisons with smoking bans.

Figure 3: Prison dischargees who smoked on entry to prison, smoking intentions on release, 2015

Notes:

-

Excludes New South Wales, as data were not provided for dischargees.

-

Only includes dischargees who smoked on entry to prison

Source: Dischargee form, NPHDC 2015.

For more information see The health of Australia's prisoners 2015 (November 2015).