Summary

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) refers to all conditions of the kidney affecting the filtration and removal of waste from the blood for 3 months or more. It is identified by reduced filtration by the kidney and/or by the leakage of protein or albumin from the blood into the urine. CKD is frequently comorbid with cardiovascular disease and diabetes (AIHW 2007, 2014).

CKD is mostly diagnosed at more advanced stages when symptoms become more apparent. Kidney failure occurs when the kidneys can no longer function adequately, at which point people require kidney replacement therapy (KRT) – a kidney transplant or dialysis – to survive.

CKD is largely preventable because many of its risk factors – high blood pressure, smoking and overweight and obesity – are modifiable. Other chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, are also risk factors for CKD (KHA 2020).

Early detection of CKD by simple blood or urine tests enables treatment to prevent or slow its progression.

How common is chronic kidney disease?

An estimated 11% of people (1.7 million Australians) aged 18 and over had biomedical signs of CKD in 2011–12, according to AIHW analysis of the Australian Bureau of Statistics latest National Health Measures Survey (NHMS) (ABS 2013) – the most recently available data on the total number of people affected by CKD in Australia (the ‘prevalence’).

The prevalence of CKD increases rapidly with age, affecting around 44% of people aged 75 and over (AIHW 2018).

Only 6.1% of NHMS respondents who showed biomedical signs of CKD self-reported having the disease, indicating that CKD is a largely under-diagnosed condition (ABS 2013).

See How many people are living with chronic kidney disease in Australia? for more information on the incidence and prevalence of CKD.

Change over time

Two national surveys have been conducted in Australia that provide data on biomarkers of CKD – the 1999–2000 Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab) and the 2011–12 NHMS. Note that the ABS is currently undertaking a multi-year Intergenerational Health and Mental Health Study in 2020–2024, which will include a new NHMS and a new National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Measures Survey (ABS 2022).

Between 1999–2000 and 2011–12, the age-standardised CKD prevalence rate remained stable, but the number of Australians with moderate to severe loss of kidney function nearly doubled, from 322,000 in 1999–2000 to 604,000 in 2011–12. This increase was mostly driven by growth in the population of older people (as people live longer) and by survival of people with kidney failure who are receiving KRT (AIHW 2018).

Kidney failure

Not everyone with kidney failure chooses to receive KRT, opting instead for end-of-life care. Therefore, estimates of the prevalence of kidney failure need to count cases both with and without replacement therapy. The most recent data available to examine this are linked data from the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) Registry and the National Death Index, covering the period 1997 to 2013 (AIHW 2016).

There were around 5,100 new cases of kidney failure in Australia in 2013, which equates to around 14 new cases per day. Of these, around 50% were receiving KRT.

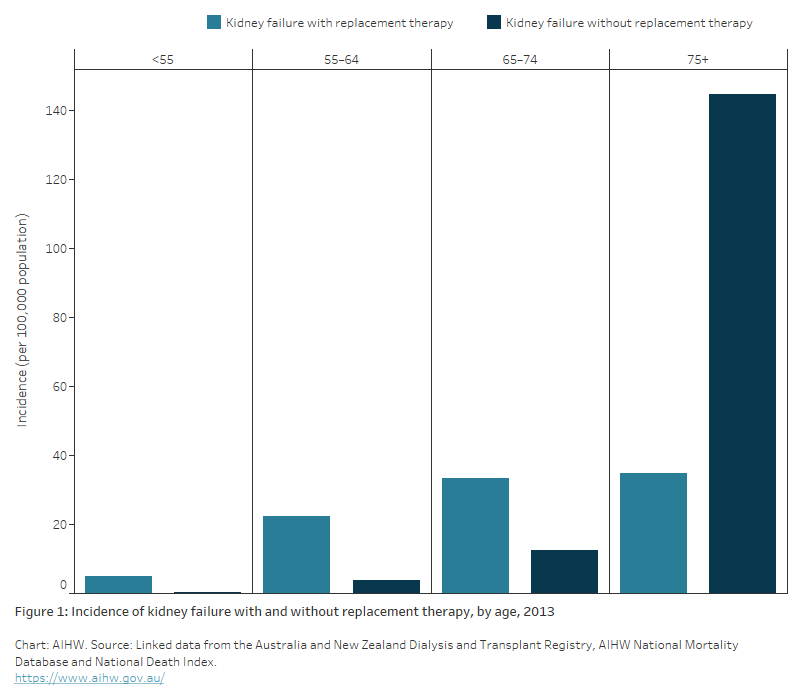

Whether people with kidney failure are treated with KRT varies with age. Before age 75, most new cases of kidney failure are treated with KRT; however, this trend reverses after age 75, where there was an 11-fold increase in kidney failure without KRT compared with that for ages 65–74 (from 13 to 145 per 100,000 population) (Figure 1) (AIHW 2016).

In 2013, 92% of people with newly diagnosed kidney failure who were aged under 55 received KRT, compared with 19% of people newly diagnosed aged 75 and over.

Figure 1: Incidence of kidney failure with and without replacement therapy, by age, 2013

The bar chart shows the incidence rate of kidney failure in 2013 by sex, age group and kidney replacement therapy (KRT) treatment status, from the AIHW analysis of the linked ANZDATA, AIHW National Mortality Database and National Death Index.

The treatment rate for new patients with kidney failure increased slightly with age from 4.8 per 100,000 population among persons aged under 55, to 35 per 100,000 population among persons aged 75 and over. In contrast, the rate of new patients with kidney failure who did not get any KRT treatment increased sharply from 0.4 per 100,000 population among those aged under 55 to 145 per 100,000 population among those aged 75 and over. These age patterns are similar for men and women, with higher kidney failure incidence rates observed for males.

Between 1997 and 2013, the number of new cases of kidney failure with KRT and without KRT increased by 71% and 35% respectively. After accounting for changes in the age structure of the population between 2001 and 2013, the incidence rate for both treatment groups remained relatively stable (AIHW 2016).

Impact of chronic kidney disease

Burden of chronic kidney disease

Burden of disease refers to the quantified impact of living with and dying prematurely from a disease or injury.

The contribution of CKD to the total disease burden (fatal and non-fatal) in Australia has remained stable since 2003. In 2023, it was responsible for 1.1% of the total burden, compared with 0.8% in 2003. In 2023 CKD was the 14th leading cause of fatal burden across all age groups, the sixth leading cause of fatal burden for women aged 85–89 and ninth leading cause of burden for men aged 85–89, respectively (AIHW 2023a).

Impaired kidney function contributes to the burden of CKD as well as several other diseases, including gout, peripheral vascular disease, dementia, coronary heart disease and stroke. In 2018, 1.9% of total disease burden could have been prevented if people had not had impaired kidney function (AIHW 2021b).

Among First Nations people, CKD was the 10th leading cause of total burden (2.5% of all burden in 2018). This was higher for females than males – CKD was the eighth leading cause of total burden among females, accounting for 3.1% of the total burden. In males, CKD accounted for 2.3% of the total burden and was the 13th leading cause (AIHW 2022b).

See Impact of chronic kidney disease for more information on the burden of CKD.

Deaths from chronic kidney disease

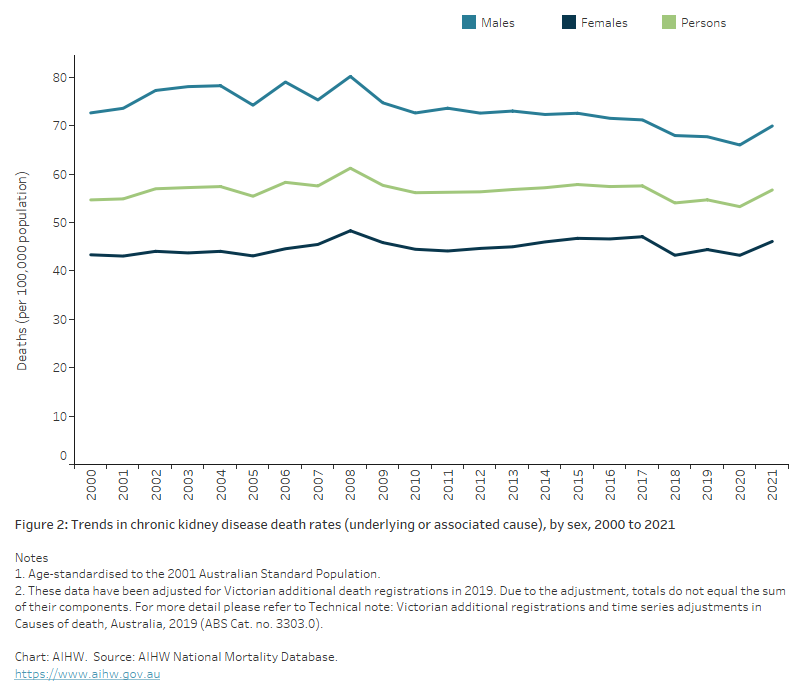

CKD contributed to around 20,000 deaths in 2021 (12% of all deaths in Australia). Twenty-three per cent of these deaths had CKD recorded as the underlying cause of death, with 77% recording CKD as an associated cause of death. The number of CKD-related deaths has increased by 97% since 2000 (when there were 10,200 deaths). The age-standardised death rate has remained stable over this time (Figure 2).

CKD is more often recorded as an associated cause of death, as the disease itself may not lead directly to death. When CKD was an associated cause of death, the most common underlying causes of death were:

- diseases of the circulatory system (33%), such as coronary heart disease, and heart failure

- cancers (20%), such as prostate, and lung

- endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases (9.4%) – in particular, type 2 diabetes

- diseases of the respiratory system (8.0%), such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumonia.

CKD is often under-reported as a cause of death, as shown by linked data from the ANZDATA Registry and the National Death Index, in which 53% of people with kidney failure who received KRT and who died between 1997 and 2013 did not have kidney failure recorded on their death certificate (AIHW 2016).

See Mortality for more information on deaths from CKD.

Figure 2: Trends in chronic kidney disease death rates (underlying or associated cause), by sex, 2000 to 2021

This graph shows the age-standardised rate of deaths where CKD was recorded as either an underlying or associated cause of death, from 2000 to 2021. Rates are higher in males than in females and have remained relatively stable. For persons, the rate of CKD deaths per 100,000 population was 55 in 2000, and 57 in 2021. The highest rate was in 2008, with 61 deaths per 100,000 population.

Treatment and management of chronic kidney disease

Hospitalisations

In 2020–21, CKD was recorded as the principal or additional diagnosis of around 2 million hospitalisations – 17% of all hospitalisations in Australia.

Dialysis was the most common reason for hospitalisation in Australia in 2020–21, accounting for 14% of all hospitalisations, and 80% of CKD hospitalisations (1.6 million). Age-standardised rates for dialysis have risen by 4.9% over the last decade.

There were 391,000 hospitalisations with a diagnosis of CKD (excluding dialysis as a principal diagnosis) in 2020–21. Eighty-five per cent of these had CKD as an additional (rather than principal) diagnosis.

The number of hospitalisations for CKD as the principal diagnosis (excluding dialysis) more than doubled between 2000–01 and 2020–21, from 24,200 to 58,200. The age-standardised hospitalisation rate for CKD as a principal diagnosis rose by 64% between 2000–01 and 2020–21.

See Hospitalisations for chronic kidney disease for more information.

Kidney replacement therapy

In 2021, around 28,500 people received KRT.

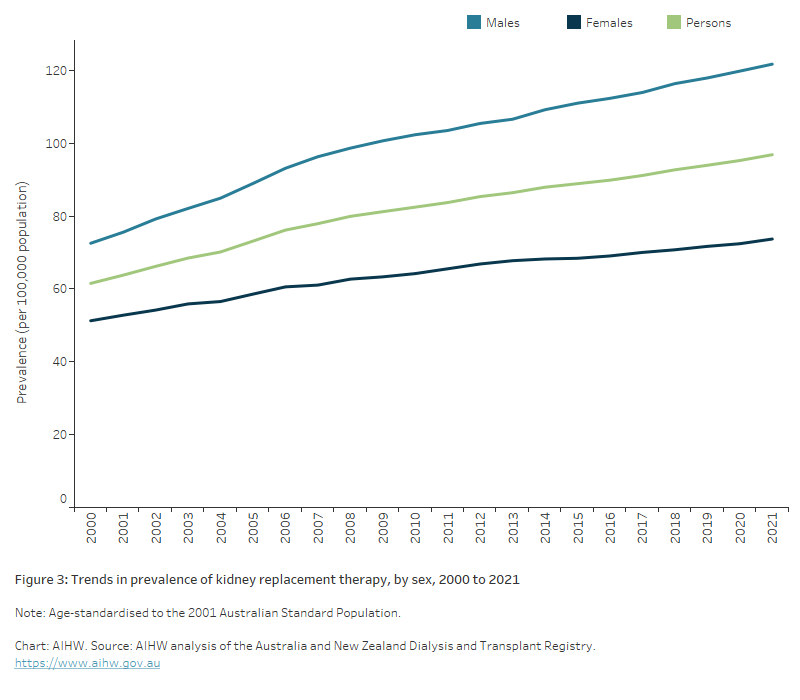

KRT rates were higher in males than females across all ages. Of all people receiving KRT, 53% had dialysis while 47% had a kidney transplant. The number of people receiving KRT has more than doubled since 2000, from around 11,700 to 28,500. The age-standardised KRT rate in 2021 was 1.6 times as high as the rate in 2000 (Figure 3).

For more information on kidney replacement therapy, see Treatment of kidney failure.

Figure 3: Trends in prevalence of kidney replacement therapy, by sex, 2000 to 2021

This graph shows the increasing trend of persons with kidney failure who are receiving kidney replacement therapy (KRT), by sex, from 2000 to 2021. The age-standardised rates have increased by 57%, from 62 per 100,000 in 2000 to 97 per 100,000 in 2021, with rates consistently higher in males than females. In 2021, the rate of persons with kidney failure receiving KRT was approximately 1.7 times higher among males (122 per 100,000 population) than females (74 per 100,00 population).

Population groups

The impact of CKD varies between population groups. To account for differences in the age structures of these groups, the data presented here are based on age-standardised rates.

CKD was 2.1 times as prevalent among First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous Australians, based on data from the 2011–12 NHMS and the 2012–13 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Measures Survey. In 2018, the overall burden of disease from CKD was 7.8 times as high in First Nations people as in non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2021a, 2022b).

Generally, the impact of CKD increases with rising socioeconomic disadvantage and remoteness. Rates of CKD hospitalisation in 2020–21 were 2.1 times as high in the lowest socioeconomic areas as in the highest, and 3.1 times as high in Remote and very remote regions as in Major cities (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Variation in the impact of chronic kidney disease between selected population groups

This table shows the relative impact of CKD in selected population groups, in terms of rates of: 1) prevalence, 2) hospitalisation, 3) death, 4) kidney failure patients receiving kidney replacement therapy, and 5) burden of disease. For each impact, rates are shown as a ratio comparing First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians, people living in Remote and Very remote areas compared to Major cities, and people living in the lowest compared to the highest socioeconomic areas. Across all measures, the impact of CKD was higher for First Nations people compared to non-Indigenous Australians, higher for people living in Remote and Very remote areas compared to Major cities, and higher for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared to the highest.

COVID-19 and chronic kidney disease

Measures to manage COVID-19 (for example, stay-at-home orders and selected service closures or suspensions) resulted in changes to health service use for people with CKD.

The number of kidney transplants from deceased donors declined by 18% in 2020 compared with 2019 as a result of the pandemic (OTA 2021). Pauses in transplant surgery particularly affect CKD, as more than half of transplanted organs are kidneys.

Over 4,700 hospitalisations in Australia involved a COVID-19 diagnosis in 2020–21. Almost 400 of these hospitalisations were for people who had a diagnosis of CKD recorded on their admission (AIHW 2022a).

In 2020–21, CKD had the third-highest hospital death rate for comorbid conditions after chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and dementia (AIHW 2022a).

CKD was present in 13.2% of COVID-19 related deaths registered in Australia by 28 February 2023 (ABS 2023).

See Impact of COVID-19 for more information on how COVID-19 has impacted the treatment and management of CKD.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2013) Australian Health Survey: biomedical results for chronic diseases, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 22 February 2022.

ABS (2013) Microdata: Australian Health Survey, Core Content – Risk Factors and Selected Health Conditions, 2011–12, AIHW analysis of detailed microdata, accessed 20 October 2021.

ABS (2022) Intergenerational Health and Mental Health Study (IHMHS) ABS, Australian Government, accessed 10 May 2022.

ABS (2023) COVID-19 Mortality in Australia: Deaths registered until 28 February 2023, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 4 April 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare), Tong B, Stevenson C (2007) Comorbidity of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 13 July 2022.

AIHW (2014) Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease – Australian facts: prevalence and incidence, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 March 2022.

AIHW (2015) Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease – Australian facts: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 March 2022.

AIHW (2016) Incidence of end-stage kidney disease in Australia 1997–2013, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 March 2022.

AIHW (2018) Chronic kidney disease prevalence among Australian adults over time, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 March 2022.

AIHW (2021a) Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 3 February 2022.

AIHW (2021b) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: interactive data on risk factor burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 16 March 2022.

AIHW (2022a) Admitted patient care 2020–21 separations with a COVID-19 diagnosis, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 6 June 2022.

AIHW (2022b) Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 16 March 2022.

AIHW (2022c) National Hospital Morbidity Database, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 10 October 2022.

AIHW (2023a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

AIHW (2023b) National Mortality Database, AHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 April 2023.

ANZDATA (Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry) (2021) ANZDATA Registry, AIHW analysis of ANZDATA, accessed 20 April 2023.

KHA (Kidney Health Australia) (2020) Risk factors of kidney disease, Kidney Health Australia website, accessed 1 September 2021.

OTA (Organ and Tissue Authority) (2020) 2020 Australian donation and transplantation activity report, OTA, Australian Government, accessed 16 March 2022.

OTA (2021) 2021 Australian donation and transplantation activity report, OTA, Australian Government, accessed 16 March 2022.