Clients with a current mental health issue

On this page

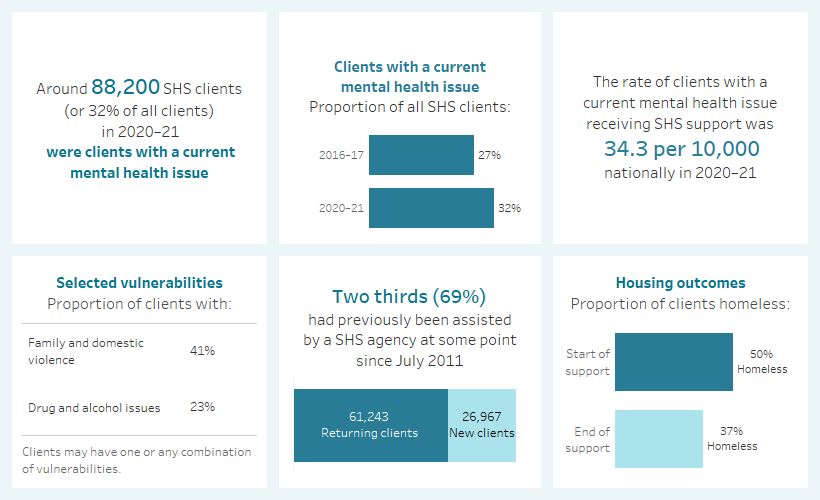

Key findings: Clients with a current mental health issue, 2020–21

Mental health is a fundamental and integral component of the health of individuals, their families, and the population (ABS 2018, AIHW 2020, Schulz & Sherwood 2008, WHO 2018, WHO 2019). Mental health is “a state of well-being in which an individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” (WHO 2018). Conversely, a mental illness may be defined as a “clinically diagnosable disorder that significantly interferes with a person’s cognitive, emotional or social abilities” (COAG Health Council 2017). The term ‘mental health issues’ captures the entire range of mental health problems and as such, clients with a current mental health issue are a diverse group, as the severity of symptoms differ between individuals.

Mental health issues are common in Australia. In any year, around 1 in 5 Australians aged 16–85 experience a mental health disorder. However, the rate of mental health issues is substantially higher among people with a history of homelessness (54%) compared to the general population (19%) (AIHW 2021a).

People with mental health issues are particularly vulnerable to experiencing homelessness (Brackertz et al. 2020). Environmental stress associated with experiences of housing instability or homelessness can trigger, exacerbate or magnify mental health issues (Brackertz et al. 2018, CHP 2018, Johnson & Chamberlain 2016, Kaleveld et al. 2018, Walter et al. 2016). Symptoms of mental illnesses that increase psychological distress and impair decision-making in daily life can contribute to worse health outcomes, reduced support and experiences of financial hardship. In this way, people with mental health issues are especially susceptible to entering or maintaining homelessness (Johnstone et al. 2016, Brackertz et al. 2020, Fazel et al. 2014).

People experiencing homelessness with mental health issues require the support of various services. Navigating through these services can be particularly challenging, and adequate support from homelessness and mental health services is crucial for these people to find and retain housing (MHCA 2009, Jones et al. 2014, Wood et al. 2016, ABS 2014).

Reporting clients with a mental health issue in the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC)

Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) clients are identified as having a current mental health issue if they are aged 10 years or older and have provided any of the following information:

- They indicated that at the beginning of support they were receiving services or assistance for their mental health issues or had in the last 12 months.

- Their formal referral source to the SHS was a mental health service.

- They reported ‘mental health issues’ as a reason for seeking assistance.

- Their dwelling type either a week before presenting to an agency, or when presenting to an agency, was a psychiatric hospital or unit.

- They had been in a psychiatric hospital or unit in the last 12 months.

- At some stage during their support period, a need was identified for psychological services, psychiatric services or mental health services.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has imposed significant health, lifestyle and economic challenges in Australia. Emerging evidence indicates there has been a negative impact on the mental health of the population since the start of the pandemic in 2020 (Dawel et al. 2020, Newby et al. 2020, NMHC 2020). Research suggests that various risk factors of poor mental health, including uncertainty, fear of potential exposure, job loss, financial strain and social isolation, have become more pervasive among the population (Biddle et al. 2020, Ricci-Cabello et al. 2020, Newby et al. 2020). A recent study, for instance, found that pandemic-related changes to social and working conditions were strongly associated with poorer mental health (Dawel et al. 2020). In 2020–21, subsidised mental health-specific services processed by Medicare increased substantially compared to previous years (AIHW 2021a). In terms of support provided by SHS agencies, there has been general upward trend in the number SHS clients with a current mental health issue since the start of the pandemic, especially among females (AIHW 2021b).

Client characteristics

Figure MH.1: Key demographics, SHS clients with a current mental health issue, 2020–21

This image describes the characteristics of around 88,200 clients with a current mental health issue and received SHS support in 2020–21. Most clients were female, aged 18–44. One fifth were Indigenous. Victoria had the greatest number of clients and Tasmania had the highest rate of clients per 10,000 population. The majority of clients had previously been assisted by a SHS agency since July 2011. Half were at risk of homelessness at the start of support. Most were in major cities.

Living arrangements and presenting unit type

In 2020–21, at the beginning of support clients with a current mental health issue (aged over 10) were more likely be living alone (40,500 clients or 47%) or as a lone parent with child(ren) (19,500 clients or 23%) rather than in a group (6,400 clients or 7.4%) or as a couple without child(ren) (4,500 or 5.3%) (Supplementary table CLIENTS.41).

Compared to other client groups, SHS clients with a current mental health issue were also more likely to present to a SHS agency alone (80% or 70,700 clients) compared with all SHS clients (63%) (Supplementary tables CLIENTS.40 and CLIENTS.9).

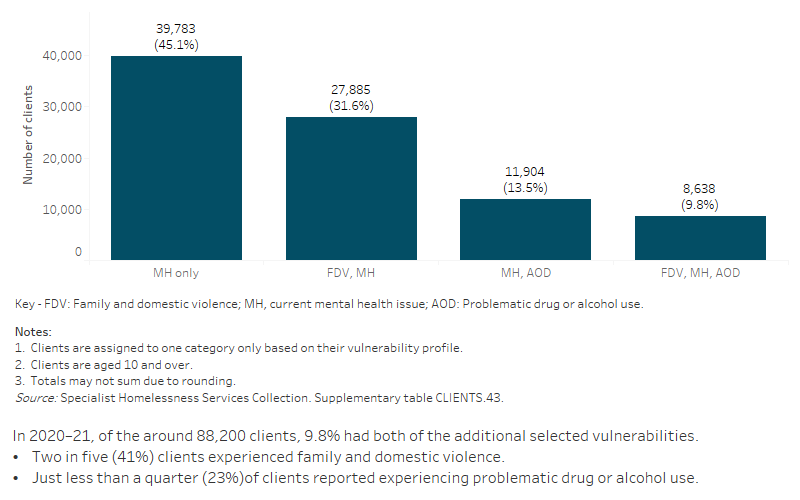

Selected vulnerabilities

In 2020–21, of the 88,200 SHS clients who had a current mental health issue, over half (55% or 48,400 clients) were experiencing additional selected vulnerabilities (Supplementary table CLIENTS.43).

These figures provide an insight into the multiple disadvantages clients experiencing mental health issues face and highlight the value of an integrated service response to homelessness for these clients (Flatau et al. 2013).

Figure MH.2: Clients with a current mental health issue, by selected vulnerability characteristics, 2020-2

Service use patterns

The length of support that clients with a current mental health issue received in 2020–21 increased to a median of 85 days compared to 75 days in 2019–20. The median number of nights accommodated increased to 48 in 2020–21 from 39 nights in 2019–20 (Supplementary table CLIENTS.44). The increases in the total number of nights of accommodation provided to clients can largely be attributed to the homelessness policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. In late March 2020, four state governments initiated programs to rapidly provide temporary accommodation to people sleeping rough to minimise the risk of community transmission (Pawson 2021, AIHW 2021b).

Changes over time since 2011–12

The number of clients with a current mental health issue receiving assistance from SHS agencies has increased at a faster rate than any other client group since the collection began in July 2011. Unlike other client groups, both the number and proportion of clients with a current mental health issue has generally increased with each successive year. Between 2011–12 and 2020–21 (Supplementary table HIST.MH):

- Clients with a current mental health issue represented over one third (32%) of all SHS clients in 2020–21, up from around one fifth (19%) in 2011–12.

- The total number of clients with a current mental health issue who received support from SHS agencies increased by an average of 7.8% annually over the 10 years to 2020–21, from 44,700 clients in 2011–12; around four times faster than for all SHS clients generally (1.8%) over the same period.

- The rate of SHS clients with a current mental health issue increased to 34.3 clients per 10,000 population, from 20.0 in 2011–12, an annual average increase of 6.1%. The annual average increase for females (7.2%) was higher than males (4.6%).

- The number of support periods that clients with a current mental health issue received from SHS agencies increased by an average of 9.5% annually over the 10 years to 2020–21; three times faster than for all SHS clients generally (3.0%) over the same period.

New or returning clients

In 2020–21, of those SHS clients with a current mental health issue (Supplementary table CLIENTS.38):

- Most (69% or nearly 61,200 clients) were returning clients, that is, they had previously received assistance from a SHS agency at some point since the collection began in July 2011.

- One-third (31% or almost 27,000 clients) were new to SHS agencies, having not previously received services.

Main reasons for seeking assistance

In 2020–21, the most common main reasons for seeking SHS assistance for clients with a current mental health issue were (Supplementary table MH.4):

- family and domestic violence (20% or 17,800 clients)

- housing crisis (20% or more than 17,400 clients)

- inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (14% or almost 12,000 clients).

Main reasons for seeking assistance at first presentation the clients experiencing homelessness and clients at risk of homelessness (Supplementary table MH.5):

- More than a quarter of clients who were at risk of homelessness at first presentation (26% or 11,000 clients) reported family and domestic violence as their main reason for seeking assistance; almost 1 in 5 (17% or 7,300 clients) reported housing crisis.

- Around 1 in 5 clients who were experiencing homelessness at first presentation reported housing crisis (23% or almost 9,900) or inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (20% or 8,300 clients) as their main reason for seeking assistance.

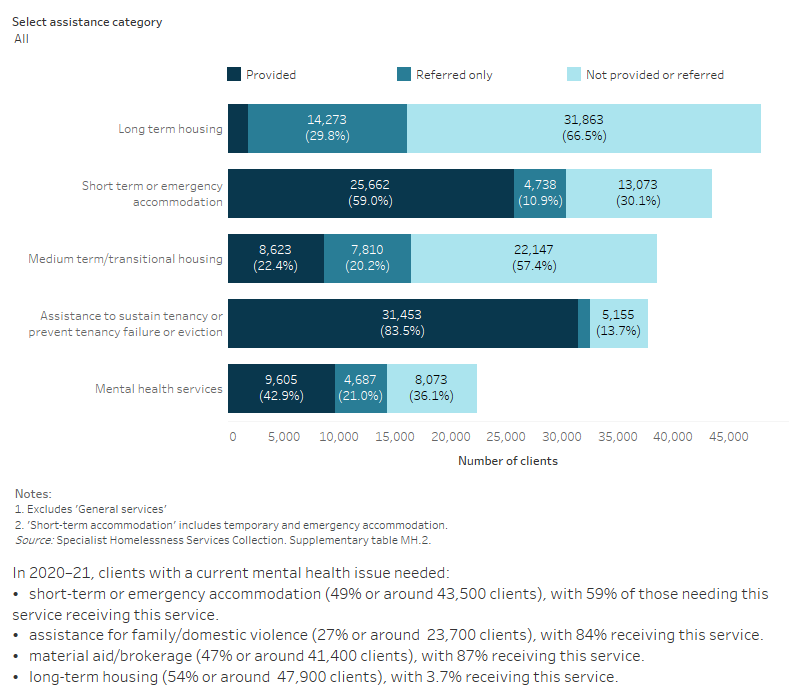

Services needed and provided

Over 1 in 4 (28% or 24,900) clients with a current mental health issue identified a need for mental health-based services (Supplementary table MH.2). Specifically:

- 25% (22,400 clients) needed mental health services, with 43% (9,600 clients) provided with this type of service.

- 10% (almost 8,900 clients) identified a need for psychological services with 32% (2,800 clients) of these requests met.

- 6.2% (5,500 clients) identified a need for psychiatric services with 33% (1,800 clients) of these requests met.

Figure MH.3: Clients with a current mental health issue, by services needed and provided, 2020-21

This interactive stacked horizontal bar graph shows the services needed by clients with a current mental health issue and their provision status. Assistance to sustain tenancy or prevent tenancy failure or eviction was the most provided service. Long term housing was the least provided service.

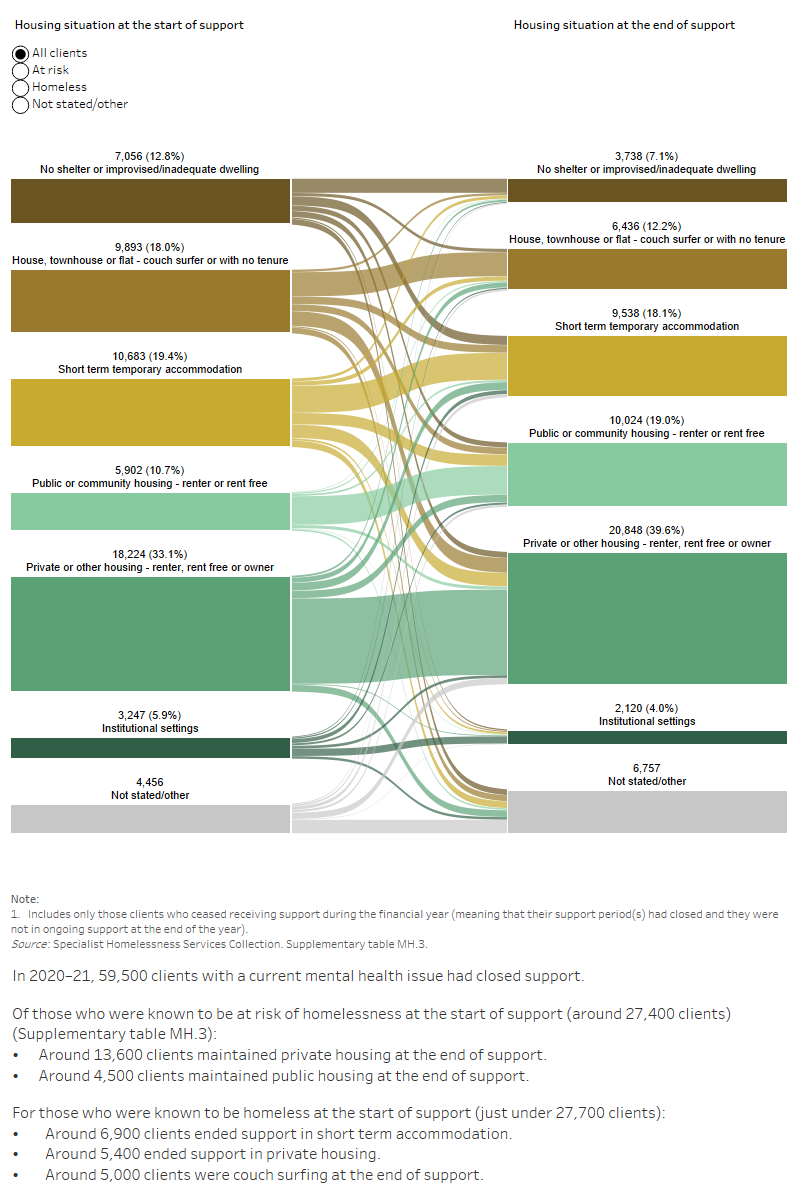

Housing situation and outcomes

Outcomes presented here describe the change in client’s housing situation between the start and end of support. Data is limited to clients who ceased receiving support during the financial year—meaning that their support periods had closed and were not receiving ongoing support at the end of the year.

Many clients had long periods of support or even multiple support periods during 2020–21. Various changes to a client’s housing situation over the course of their support partly explains this occurrence. These changes throughout the year are not reflected in the data presented. Instead, only the client situation at the start of their first support period in 2020–21 is compared with the end of their last support period in 2020–21. A proportion of these clients may have sought assistance prior to 2020–21, and may seek assistance again in the future.

In 2020–21, half (50% or 27,600 clients) of clients with a current mental health issue were experiencing homelessness at the start of support; almost 10,700 (19%) were in short-term temporary accommodation and almost 9,900 (18%) were couch surfing.

By the end of support, fewer clients with a current mental health issue were known to be experiencing homelessness (37%); most (63%) were living in stable accommodation, be it public or community, private or other housing or an institutional setting (Supplementary table MH.3).

Figure MH.4: Housing situation for clients with a current mental health issue with closed support, 2020–21

This interactive Sankey diagram shows the housing situation (including rough sleeping, couch surfing, short-term accommodation, public/community housing, private housing and institutional settings) of clients with a current mental health issue with closed support periods at first presentation and at the end of support. The diagram shows clients’ housing situation journey from start to end of support. Most started and ended support in private housing.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2008) National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results, 2007, ABS Cat. No. 4326.0, ABS, Canberra.

ABS (2014) Mental Health and Experiences of Homelessness, Australia, 2014, ABS Cat. No. 4329.0.00.005. ABS, Canberra.

ABS (2018) National Health Survey: First Results 2017–18, ABS Cat. No. 4364.0.55.001, ABS, Canberra.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2020) Mental health, AIHW, accessed 5 October 2021.

AIHW (2021a) Mental health services in Australia, AIHW, accessed 5 October 2021.

AIHW (2021b) Specialist Homelessness Services: monthly data. Cat. no. HOU 321. AIHW, Canberra.

Biddle N, Edwards B, Gray M & Sollis K (2020) Hardship, distress, and resilience: The initial impacts of COVID-19 in Australia, COVID-19 Briefing Paper, ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, Australian National University, Canberra.

Brackertz N, Borrowman L, Roggenbuck C, Pollock S & Davis E (2020) Trajectories: the interplay between mental health and housing pathways: Final research report, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited and Mind Australia, Melbourne.

Brackertz N, Wilkinson A & Davison J (2018) Housing, homelessness and mental health: towards systems change, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

CHP (Council to Homeless Persons) (2018) Housing Security, Disability and Mental Health, Parity October 2018, accessed 5 October 2021.

COAG (Council of Australian Governments) Health Council (2017) The Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan, Department of Health, Canberra.

Dawel A, Shou Y, Smithson M, Cherbuin N, Banfield M, Calear AL, Farrer LM, Gray D, Gulliver A, Housen T, McCallum SM, Morse AR, Murray K, Newman E, Rodney Harris RM and Batterham PJ (2020) The Effect of COVID-19 on Mental Health and Wellbeing in a Representative Sample of Australian Adults, Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11:579985. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579985

Fazel S, Geddes JR & Kushel M (2014) The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations, The Lancet, 384(9953), 1529-1540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

Flatau P, Conroy E, Thielking M, Clear A, Hall S, Bauskis A, Farrugia M & Burns L (2013) How integrated are homelessness, mental health and drug and alcohol services in Australia? AHURI Final Report No. 206, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Johnson G & Chamberlain C (2016) Are the Homeless Mentally Ill?, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 46(1):29–48. doi: 10.1002/j.1839-4655.2011.tb00204.x

Johnstone M, Parsell C, Jetten J, Dingle G & Walter Z (2016) Breaking the cycle of homelessness: Housing stability and social support as predictors of long-term well-being, Housing Studies, 31(4):410-426. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2015.1092504

Jones A, Phillips R, Parsell C & Dingle, G (2014) Review of systemic issues for social housing clients with complex needs, Institute for Social Science Research, The University of Queensland, Brisbane.

Kaleveld L, Seivwright A, Box E, Callis Z & Flatau P (2018) Homelessness in Western Australia: A review of the research and statistical evidence, Government of Western Australia, Department of Communities, Perth.

MHCA (Mental Health Council of Australia) (2009) Home Truths: Mental Health, Housing and Homelessness in Australia, MHCA, Canberra.

Newby JM, O’Moore K, Tang S, Christensen H, Faasse K (2020) Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, PLOS ONE, 15(7): e0236562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236562

NMHC (National Mental Health Commission) (2020) National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan, NMHC, accessed 28 September 2021.

Pawson (2021) COVID-19 effects on housing and homelessness: the story to mid-2021, Australia’s welfare 2021 data insights: Australia’s welfare series no. 15, Chapter 5. Cat. no. AUS 236. AIHW: Canberra.

Ricci-Cabello I, Meneses-Echavez JF, Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Fraile-Navarro D, Fiol de Roque MA, Pastor-Moreno GP, Castro A, Ruiz-Pérez I, Campos RZ, Gonçalves-Bradley DC (2020) Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: a rapid systematic review, Journal of Affective Disorders, 277(1):347-357. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.034

Schulz R & Sherwood PR (2008) Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving, The American journal of nursing, 108(9):23–27. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c

Walter ZC, Jetten J, Dingle GA, Parsell C & Johnstone M (2016) Two pathways through adversity: Predicting well‐being and housing outcomes among homeless service users, British Journal of Social Psychology, 55(2):357-74. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12127

WHO (World Health Organization) (2018) Mental Health: Strengthening our response, WHO, accessed 28 September 2021.

WHO (2019) The WHO special initiative for mental health (2019-2030): universal health coverage for mental health, WHO, accessed 28 September 2021.

Wood L, Flatau P, Zaretzky K, Foster S, Vallesi S & Miscenko D (2016) What are the health, social and economic benefits of providing public housing and support to formerly homeless people?, AHURI Final Report No. 265, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne, doi:10.18408/ahuri-8202801.