Clients who are current or former members of the Australian Defence Force

The long-term welfare of Australian Defence Force (ADF) members is of importance as the nature of military service may mean serving and ex-serving personnel are exposed to a greater number of risk factors that may influence their likelihood of experiencing homelessness, including:

- Complex personal needs – mental health issues and other complex vulnerabilities can be reflective of the unique demands of service (McFarlane et al. 2011).

- Financial stress – employment can become an issue for ADF members when transitioning from service to civilian life (Searle et al. 2019).

At 30 June 2018, there were more than 58,000 permanent current ADF members (Defence 2018). In addition, as at 30 June 2018, there were estimated to be around 641,300 living veterans, this figure includes all living persons who have ever served in the ADF either full-time or as reservists (DVA 2018).

Serving ADF personnel have access to housing and rental assistance through Defence Housing Australia. However, once personnel discharge from the ADF they are no longer able to access this housing support. Current or former ADF members can access a range of housing and homelessness services through government and non-government organisations (Defence 2017). To provide a better understanding of the extent to which current or former ADF members may need support from specialist homelessness services (SHS), the Australian Defence Force (ADF) indicator was introduced into the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC) in July 2017.

It is important to note that variability in the implementation of this item means that coverage is incomplete and limited analyses are possible for 2018–19. As is common with new data items, there was a high number of ‘don’t know’ (9%, down from 14% in 2017–18) or ‘not applicable’ (30%, up from 29% in 2017–18) responses to the ADF question in 2018–19. A ‘don’t know’ response is selected if the information is not known or the client refuses to provide the information while a ‘not applicable’ response is selected if the client is under the age of 18. Expectations are that data quality will improve over time. Further details about the ADF indicator in the SHSC are provided in the Technical information section.

The Use of specialist homelessness services by ex-serving ADF members 2011–12 to 2016–17 report used linked data to identify contemporary ex-serving ADF members (those who discharged after 1 January 2001) who had used services between 2011–12 and 2016–17. The report provides a longer term view of client, prior to the implementation of the ADF indicator in the SHSC.

Reporting ADF clients in the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC)

The SHS ADF indicator is applied when a client self-identifies as a current or former ADF member. The ADF indicator is not applicable to clients who may have served in non-Australian defence forces, reservists who have never served as a permanent ADF member or clients under the age of 18. Note that differences between the results of this and other publicly reported estimates may be due to differences in how an ADF member is defined. Further details about the ADF indicator in the SHSC are provided in Technical information.

Key findings

- In 2018–19, specialist homelessness services agencies assisted around 1,400 clients who identified as current or former members of the Australian Defence Force, up from almost 1,300 clients in 2017–18.

- Two-thirds were male (67% or more than 900 clients).

- Overall, more than a quarter of clients were aged 45–54 (27% or almost 400 clients).

- More than half (52% or around 700 clients) were known to be homeless when they sought assistance and 60% (more than 800 clients) were living alone.

- 65%, or more than 900 clients, had received SHS support before, with a high proportion of males aged 45–54 returning in 2018–19 (32% or almost 200 clients).

Client characteristics

In 2018–19, clients who self-identified as current or former members of the ADF (Table ADF.1):

- received a median of 58 days and 23 nights of support.

- had an average of 2.8 support periods per client.

- almost 2 in 3 (65%) had a case management plan and 1 in 5 (19%) had all case management goals achieved.

More than half (52%) of clients who were ADF members were experiencing homelessness at the time of seeking SHS support, which was higher than the general SHS population (42%).

|

|

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|---|---|---|

|

Number of clients |

1,295 |

1,406 |

|

Housing situation at the beginning of the first support period (proportion (per cent) of all clients) |

||

|

Homeless |

49 |

52 |

|

At risk of homelessness |

51 |

48 |

|

Length of support (median number of days) |

53 |

58 |

|

Average number of support periods per client |

3.1 |

2.8 |

|

Proportion receiving accommodation |

36 |

40 |

|

Median number of nights accommodated |

31 |

23 |

|

Proportion of a client group with a case management plan |

65 |

65 |

|

Achievement of all case management goals (per cent) |

20 |

19 |

Notes

- The denominator for the proportion receiving accommodation is all SHS clients who have identified as current or former members of the Australian Defence Force. Denominator values for proportions are provided in the relevant supplementary table.

- The denominator for the proportion achieving all case management goals is the number of client groups with a case management plan. Denominator values for proportions are provided in the relevant supplementary table.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2017–18 to 2018–19.

Age and sex

In 2018–19, of clients who identified as current or former members of the ADF (Supplementary table ADF.1):

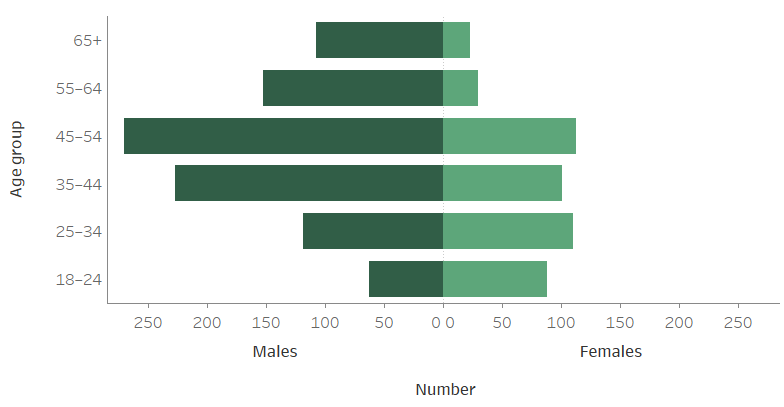

- Two-thirds (67% or more than 900 clients) were male (compared with 40% in the general SHS population) and more than a quarter (27% or almost 400 clients) were aged 45–54 (Figure ADF.1).

- More than twice the proportion of young females (aged 18–34) sought SHS support when compared with young males aged 18–34 (43% or 200 clients compared with 19% or 180 clients).

- There were more females aged 18–24 years than males, however there were more males than females in every other age category.

Figure ADF.1: Clients who are current or former members of the Australian Defence Force, by age and sex, 2018–19

Notes

- The Australian Defence Force (ADF) indicator was introduced into the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC) in July 2017.

- The ADF indicator is not applicable to clients who may have served in non-Australian defence forces or reservists who have never served as a permanent ADF member.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2018–19, Supplementary table ADF.1.

States and territories

In 2018–19, the highest number of clients accessed services in Victoria (44% or more than 600 clients) (Table ADF.2).

|

|

NSW |

Vic |

Qld |

WA |

SA |

Tas |

ACT |

NT |

National |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number |

312 |

624 |

257 |

94 |

67 |

54 |

17 |

52 |

1,406 |

|

Housing situation at the beginning of support |

|||||||||

|

Homeless |

183 |

258 |

156 |

49 |

38 |

29 |

3 |

25 |

691 |

|

At risk of homelessness |

107 |

312 |

92 |

41 |

20 |

24 |

12 |

25 |

619 |

Notes

- Housing situation at the start of support excludes not stated/other.

- Clients may access services in more than one state or territory. Therefore the total will be less than the sum of jurisdictions.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2018–19.

Living arrangements

In 2018–19, of clients who identified as current or former members of the ADF (Supplementary table ADF.4):

- On presentation to services for assistance more than half of clients (52%) were currently experiencing homelessness (compared with 42% of the general SHS population). Of those presenting homeless:

- 40% (almost 300 clients) were rough sleeping (compared with 22% of the general SHS population)

- 36% (around 250 clients) were in short-term or emergency accommodation (compared with 38% of the general SHS population).

- Just under half (48%) presented to services at risk of homelessness (compared with 58% of the general SHS population). Of those:

- 61% were in private or other housing (compared with 61% of the general SHS population)

- 19% were in public or community housing (compared with 23% of the general SHS population).

New and returning clients

In 2018–19, clients were either presenting to SHS agencies for the first time as new clients or had previously been assisted by a SHS agency at some point since the collection began in 2011–12 (Supplementary table ADF.7). More than a third of clients in 2018–19 were new (35% or almost 500 clients; compared with 45% of the general SHS population). One in 4 (25%) new clients were aged 45–54 years and an additional 1 in 5 (21%) were aged 35–44 years. Of those clients returning to SHS agencies for assistance (65% or around 900 clients), males were more likely to be aged 45–54 (32% or almost 200 clients), while females were more likely to be aged 25–34 (25% or almost 100 clients).

Selected vulnerabilities

SHS clients can face additional vulnerabilities that make them more susceptible to experiencing homelessness, in particular family and domestic violence, a current mental health issue and problematic drug and/or alcohol use.

In 2018–19, of the more than 1,400 clients who self-identified as members of the ADF, almost 2 in 3 (66%) reported experiencing one or more of these vulnerabilities:

- 3 in 10 reported experiencing a current mental health issue only (30% or more than 400 clients).

- More than 1 in 10 (12%) reported both a current mental health issue and problematic drug and/or alcohol use.

- 4% reported problematic drug and/or alcohol use only.

- 1 in 5 (20%) reported problematic drug and/or alcohol use, as a single vulnerability or in combination with other vulnerabilities.

- More than 1 in 5 (22%) reported experiencing family and domestic violence.

- 4% reported experiencing all 3 vulnerabilities.

|

Family and domestic violence |

Mental health issue |

Problematic drug and |

Clients |

Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

51 |

3.6 |

|

Yes |

Yes |

No |

141 |

10.0 |

|

Yes |

No |

Yes |

8 |

0.6 |

|

No |

Yes |

Yes |

163 |

11.6 |

|

Yes |

No |

No |

103 |

7.3 |

|

No |

Yes |

No |

416 |

29.6 |

|

No |

No |

Yes |

53 |

3.8 |

|

No |

No |

No |

471 |

33.5 |

|

|

|

|

1,406 |

100.0 |

Notes

- Clients are assigned to one category only based on their vulnerability profile.

- Clients are aged 18 and over.

- Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2018–19.

Main reasons for seeking assistance

SHS agencies provide a range of support services. For clients who self-identified as current or former members of the ADF receiving SHS support in 2018–19 (Supplementary table ADF.5 and ADF.6):

- The main reason for seeking assistance was housing crisis (26% or more than 350 clients), followed by financial difficulties (15% or around 200 clients).

- Both homeless and at risk clients most commonly identified housing crisis as their main reason for seeking assistance (29% or 200 clients and 23% or around 150 clients respectively).

- Clients at risk of homelessness were more likely to report financial difficulties as a main reason for seeking assistance (21% or more than 100 clients) than clients presenting as homeless (9% or less than 100 clients).

Services needed and provided

In 2018–19, the provision of support services to clients varied based on their identified need on presentation (Supplementary table ADF.3):

- Advice/information was most likely to be needed by clients (87% or more than 1,200 clients) and was provided to 99% (or around 1,200 clients).

- More than 2 in 3 (69%) clients needed accommodation and it was provided to more than half of those who needed it (59%). Three in 10 clients were unable to be provided or referred accommodation when a need was identified (30% or almost 300 clients).

Compared with the general SHS population, clients who self-identified as members of the ADF were more likely to need:

- financial information (34% compared with 26% in the general SHS population)

- health/medical services (17% compared with 9%)

- mental health services (14% compared with 8%).

Housing outcomes

For clients with a known housing status who were at risk of homelessness at the start of support (450 clients), by the end of support (Interactive Tableau visualisation):

- Half (around 250 clients or 55%) were in private housing

- Around 100 clients (18%) were in public or community housing.

For clients who were known to be homeless at the start of support (just over 400 clients), agencies were able to assist:

- More than 100 clients (28%) into short term accommodation

- 100 (22%) into private housing.

References

Defence (Department of Defence) 2018. Defence Annual Report 2017–18. Canberra: Department of Defence.

Defence 2017. ADF member and family transition guide: a practical manual to transitioning. Canberra: Department of Defence.

DVA (Department of Veterans Affairs) 2018. Department of Veterans’ Affairs Annual Report 2017–18. Canberra: Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

McFarlane A, Hodson S, Van Hooff M & Davies C 2011. Mental health in the Australian Defence Force: 2010 ADF Mental Health and Wellbeing Study: Full report, Department of Defence: Canberra.

Searle, A, Van Hooff M, Lawrence-Wood E, Hilferty F, Katz I, Zmudzki F & McFarlane A 2019. Homelessness amongst Australian contemporary veterans: pathways from military and transition risk factors, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), Melbourne: AHURI.