Clients exiting custodial arrangements

On this page

Upon release, people discharged from prison can face stigma associated with a history of incarceration and discrimination from landlords and potential employers (Schetzer & StreetCare 2013). Prisoners applying for parole may experience difficulties securing appropriately located and affordable accommodation, leading to refusal of parole or breach of parole conditions and subsequent return to prison. Parole officers must approve accommodation conditions for the duration of parole and if the assigned accommodation (including temporary or supported accommodation) becomes unavailable, it puts these people in breach of their parole conditions (Schetzer & StreetCare 2013).

Prison dischargees need housing and employment for successful re-entry into the community and to reduce the likelihood of returning to prison. Without secure housing, people who are released from prison often cycle from prison into homelessness and back into prison. Prison dischargees who experience homelessness are almost twice as likely to return to prison within 9 months of release (Baldry et al. 2006). Offering pre-release support and planning, and integrated case management post-release can help people exiting custody to secure accommodation and address other transitional needs (Schetzer & StreetCare 2013).

Young people leaving youth detention can also become entangled in a cycle of detention and homelessness. Housing instability and homelessness are often cited as drivers of an increasing youth detention population, with young people remanded in detention ‘for their own good’ due to a lack of appropriate options for accommodation (Cunneen et al. 2016; Richards 2011). Among those released from detention, 8% of young people accessed homelessness support within 12 months of release (AIHW 2012). Often, people with a history of youth justice supervision remain vulnerable to homelessness in adulthood. Adults who were previously under youth justice supervision are almost twice as likely to sleep rough or in squats (Bevitt et al. 2015).

On 30 June 2019, there were 43,000 adult prisoners in Australian prisons (ABS 2019). More than half (54%) of prison dischargees expect to be homeless upon release, with 44% of prison dischargees planning to stay in short-term or emergency accommodation (AIHW 2019). Having stable accommodation helps people exiting prison to transition successfully into society and reduces the likelihood of reoffending. Currently, 46% of prison dischargees return to prison with a new sentence within two years (SCRGSP 2020a). With the cost of imprisonment at $113,000 per person per year, there are substantial cost savings associated with decreasing the rate of recidivism in Australia (SCRGSP 2020b).

People exiting institutions and care into homelessness are a national priority homelessness cohort identified in the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement which came into effect on 1 July 2018 (CFFR 2018) (see Policy section for more information).

Reporting clients exiting custodial arrangements in the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC)

In the SHSC, a client is identified as leaving a custodial setting if, in their first support period during the reporting period, either in the week before or at presentation:

- their dwelling type was adult correctional facility, youth/juvenile justice detention centre or immigration detention centre

- they identified transition from custodial arrangements as a reason for seeking assistance, or

- their source of formal referral to the agency was youth or juvenile justice detention centre or adult correctional facility.

Some of these clients were still in custody at the time they began receiving support. Note, in the SHSC, it is not possible to distinguish between clients who have sought assistance without leaving an institutional setting and those who may have left an institutional setting but returned prior to the end of support.

Children aged under 10 cannot be charged with a criminal offence in Australia. Therefore, clients aged under 10 who were identified as exiting from adult correctional facilities or youth/juvenile justice detention centres have been excluded.

For more information, see Technical information.

Key findings

- In 2019–20, almost 9,500 SHS clients were exiting custodial arrangements, comprising 3% of all clients.

- The majority of clients exiting custody (71% or almost 6,800 clients) had received assistance from a SHS agency at some point since the collection began in 2011–12.

- Around 4 in 5 (78%) clients exiting custody were male.

- Almost 1 in 3 (31%) clients exiting custody were aged 35–44 and a further 1 in 3 (31%) were aged 25–34.

- Half (48%) had reported a mental health issue and 1 in 3 (34%) had reported problematic drug and/or alcohol use.

- Clients exiting custody were more likely than the overall SHS population to need certain services such as assistance with challenging social/behavioural problems (18% of clients exiting custody), drug/alcohol counselling (10%) and employment assistance (10%).

- The most common housing situation for clients exiting custody, at both the beginning and end of support, was institutional settings. The proportion of clients staying in institutional settings decreased from 62% to 43% at the end of support.

- There was an increase in the proportion of clients who were homeless at the end of support from 31% to 35%.

Client characteristics

In 2019–20 (Table EXIT.1):

- SHS agencies assisted almost 9,500 clients who were exiting custodial arrangements. This comprised 3% of all SHS clients in 2019–20.

- There were around 100 fewer SHS clients exiting custodial arrangements compared with 2018–19. There was an increase in the number of clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2018–19 but the number has remained stable since then.

- The rate of SHS clients exiting custodial arrangements was 3.7 per 10,000 population, decreasing from 3.8 in 2018–19.

| 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Number of clients | 7,800 | 8,112 | 8,338 | 9,577 | 9,452 |

Proportion of all clients | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

Rate (per 10,000 population) | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 3.7 |

Notes

- Rates are crude rates based on the Australian estimated resident population (ERP) at 30 June of the reference year. Minor adjustments in rates may occur between publications reflecting revision of the estimated resident population by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Data for 2015–16 to 2016–17 have been adjusted for non-response. Due to improvements in the rates of agency participation and SLK validity, data from 2017–18 are not weighted. The removal of weighting does not constitute a break in time series and weighted data from 2015–16 to 2016–17 are comparable with unweighted data for 2017–18 onwards. For further information, please refer to the Technical Notes.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2015–16 to 2019–20.

Age and sex

In 2019–20 (Supplementary table EXIT.1):

- The majority of clients exiting custodial arrangements were male (78% or over 7,300 clients).

- Clients exiting custodial arrangements had an older age profile than the overall SHS population, with 1 in 3 aged 35–44 (31% or over 2,900 clients) and a further 1 in 3 aged 25–34 (31% or almost 2,900 clients).

- Although fewer clients exiting custodial arrangements were female (around 2,100 clients), a higher proportion of female clients were under 18 (11%, compared with 5% males).

Indigenous status

In 2019–20, of the clients who were exiting custodial arrangements and whose Indigenous status was known (Supplementary table EXIT.8):

- Over 1 in 4 (27% or almost 2,500 clients) identified as Indigenous

- Female clients who were exiting custodial arrangements were more likely than male clients to identify as Indigenous (36%, compared with 25% of males).

State and territory

In 2019–20 (Supplementary table EXIT.2):

- Half of the SHS clients exiting custodial arrangements nationally accessed services in Victoria (51% or around 4,800 clients). Since 2017–18, 1,200 more clients identified as exiting custodial arrangements in Victoria, contributing to the increase in the number of clients exiting custodial arrangements nationally (Historical table HIST.EXIT).

- New South Wales recorded the second highest number of clients exiting custodial arrangements (22% or around 2,100 clients).

- Despite having one of the lowest numbers of clients exiting custodial arrangements (230 clients), the Northern Territory had the highest rate of clients exiting custodial arrangements (9.3 clients per 10,000 population).

Living arrangement

In 2019–20, of the almost 9,500 clients who were exiting custodial arrangements and stated their living arrangement at the beginning of SHS support (Supplementary table EXIT.10):

- 3 in 4 (75% or more than 6,900 clients) were living alone

- 15% (almost 1,400 clients) were living with a group

- female clients were more likely to be living as a single parent with one or more children (11%, compared with 2% males) or with other family (6%, compared with 3% males).

New or returning clients

In 2019–20 (Supplementary table EXIT.7):

- Of the 9,500 clients exiting custodial arrangements, 29% (around 2,700 clients) were new to the SHSC in 2019–20 and 71% (almost 6,800 clients) were returning clients, having previously been assisted by an SHS agency at some point since the collection began in 2011–12.

- New clients exiting custodial arrangements were more likely to be under 18 (12%, compared with 5% of returning clients).

- While female clients comprised 22% of all clients exiting custodial arrangements, a higher proportion were returning clients (78%, compared with 69% males).

Selected vulnerabilities

Clients may face challenges that make them more vulnerable to experiencing homelessness. The vulnerabilities presented here include family and domestic violence, a current mental health issue and problematic drug and/or alcohol use.

In 2019–20, of the almost 9,500 clients exiting custodial arrangements, 3 in 5 (61%) reported experiencing one or more of these vulnerabilities (Table EXIT.2):

- almost half (48% or around 4,500 clients) reported a current mental health issue, as a single vulnerability or in combination with other vulnerabilities.

- 1 in 3 (34% or around 3,200 clients) reported problematic drug and/or alcohol use, as a single vulnerability or in combination with other vulnerabilities.

- 18% (almost 1,700 clients) reported both a current mental health issue and problematic drug and/or alcohol use.

- 15% (over 1,400 clients) reported experiencing family and domestic violence, as a single vulnerability or in combination with other vulnerabilities.

- 7% (around 620 clients) reported experiencing all 3 vulnerabilities.

- 2 in 5 clients (39% or around 3,700 clients) reported experiencing none of these vulnerabilities.

Family and domestic violence | Mental health issue | Problematic drug and | Clients | Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Yes | Yes | Yes | 616 | 6.5 |

Yes | Yes | No | 357 | 3.8 |

Yes | No | Yes | 144 | 1.5 |

No | Yes | Yes | 1,674 | 17.7 |

Yes | No | No | 313 | 3.3 |

No | Yes | No | 1,880 | 19.9 |

No | No | Yes | 801 | 8.5 |

No | No | No | 3,667 | 38.8 |

|

|

| 9,452 | 100.0 |

Notes

- Clients are assigned to one category only based on their vulnerability profile.

- Clients are aged 10 and over.

- Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2019–20.

Housing situation on first presentation

At the beginning of their first support period in 2019–20, 1 in 3 (34%) clients exiting custodial arrangements were experiencing homelessness when they presented to a SHS agency while 67% were at risk of homelessness (Supplementary table CLIENTS.12).

Service use patterns

In 2019–20, clients exiting custodial arrangements received (Table EXIT.3):

- a median of 46 days of support, an increase from 44 days in 2018–19

- an average of 2.0 support periods per client

- a median of 16 nights of accommodation, with almost 2 in 5 (38%) receiving accommodation

| 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Length of support (median number of days) | 44 | 45 | 49 | 44 | 46 |

Average number of support periods per client | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

Proportion receiving accommodation | 38 | 35 | 37 | 36 | 38 |

Median number of nights accommodated | 26 | 28 | 22 | 18 | 16 |

Notes

- The denominator for the proportion receiving accommodation is all SHS clients who have exited custodial arrangements. Denominator values for proportions are provided in the relevant supplementary table.

- Data for 2015–16 to 2016–17 have been adjusted for non-response. Due to improvements in the rates of agency participation and SLK validity, data from 2017–18 are not weighted. The removal of weighting does not constitute a break in time series and weighted data from 2015–16 to 2016–17 are comparable with unweighted data for 2017–18 onwards. For further information, please refer to the Technical Notes.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2015–16 to 2019–20.

Main reasons for seeking assistance

In 2019–20, the main reasons for seeking assistance among clients exiting custodial arrangements were (Supplementary table EXIT.5):

- transition from custodial arrangements (66% or almost 6,200 clients)

- housing crisis (7% or almost 700 clients)

- inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (6% or 560 clients).

Clients exiting custodial arrangements who were at risk of homelessness at first presentation were more likely to identify transition from custodial arrangements as their main reason for seeking assistance (77%, compared with 44% experiencing homelessness) (Supplementary table EXIT.6).

Clients exiting custodial arrangements who were experiencing homelessness at first presentation were more likely to report housing crisis (14%, compared with 4% at risk) or inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (14%, compared with 2% at risk) as their main reason for seeking assistance.

Services needed and provided

Similar to the overall SHS population, clients exiting custodial arrangements needed general services that were provided by SHS agencies including advice/information, advocacy/liaison on behalf of client and other basic assistance.

Apart from these general services, the most common services needed by clients exiting custody were (Supplementary table EXIT.3):

- short-term or emergency accommodation (55% or over 5,100 clients), with 60% receiving this service

- long-term housing (50% or almost 4,800 clients), with 3% receiving this service and a further 24% referred for this service

- assistance to sustain tenancy or prevent tenancy failure or eviction (44% or almost 4,200 clients), with 88% receiving this service

- medium-term/transitional housing (38% or around 3,600 clients), with 18% receiving this service and a further 21% referred for this service.

Clients exiting custody were more likely than all SHS clients to need services including:

- assistance with challenging social/behavioural problems (18%, compared with 12%), with 84% receiving this service

- drug/alcohol counselling (10%, compared with 4%), with 40% receiving this service

- employment assistance (10%, compared with 6%), with 61% receiving this service.

Outcomes at the end of support

Outcomes presented here describe the change in clients’ housing situation between the start and end of support. Data is limited to clients who ceased receiving support during the financial year—meaning that their support periods had closed and they did not have ongoing support at the end of the year.

Many clients had long periods of support or even multiple support periods during 2019–20. They may have had a number of changes in their housing situation over the course of their support. These changes within the year are not reflected in the data presented here, rather the client situation at the start of their first support period in 2019–20 is compared with the end of their last support period in 2019–20. A proportion of these clients may have sought assistance prior to 2019–20, and may again in the future.

In 2019–20 (Table EXIT.4):

- The most common housing situation for clients exiting custodial arrangements at both the beginning and end of SHS support was institutional settings; over 4,300 clients (62%) at the beginning and around 2,800 clients (43%) at the end of support. Institutional settings include dwelling types such as adult correctional facilities, youth/juvenile justice correctional centres and immigration detention centres, and this housing situation is considered at risk of homelessness rather than homeless.

- Over 1 in 3 (35%) clients exiting custodial arrangements were known to be homeless at the end of support, an increase from 31% at the beginning of support.

- Almost 2 in 3 (65%) clients exiting custodial arrangements were known to be housed at the end of support, a decrease from 69% at the beginning of support.

- Although more clients were known to be homeless at the end of support with clients leaving institutional settings, the proportion living in public or community housing increased from 3% to 11% (an increase of almost 490 clients) at the end of support and the proportion of clients living in private or other housing increased from 5% to 11% (an increase of around 400 clients).

- Clients who were known to be homeless were most likely to be staying in short-term temporary accommodation. The proportion of clients in short-term temporary accommodation increased from 14% to 20% at the end of support.

These trends demonstrate that known housing outcomes at the end of support can be challenging for clients transitioning from institutional settings. While some clients progressed towards more positive housing solutions, many remained in institutional settings, returned to institutional settings or were in temporary accommodation at the end of support.

Housing situation | Beginning of support | End of | Beginning of support | End of |

|---|---|---|---|---|

No shelter or improvised/inadequate dwelling | 527 | 352 | 7.5 | 5.4 |

Short term temporary accommodation | 983 | 1,267 | 13.9 | 19.5 |

House, townhouse or flat - couch surfer or with no tenure | 671 | 644 | 9.5 | 9.9 |

Total homeless | 2,181 | 2,263 | 30.9 | 34.8 |

Public or community housing - renter or rent free | 200 | 688 | 2.8 | 10.6 |

Private or other housing - renter, rent free or owner | 341 | 738 | 4.8 | 11.4 |

Institutional settings | 4,342 | 2,809 | 61.5 | 43.2 |

Total at risk | 4,883 | 4,235 | 69.1 | 65.2 |

Total clients with known housing situation | 7,064 | 6,498 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Not stated/other | 264 | 830 |

|

|

Total clients | 7,328 | 7,328 |

|

|

Notes

- Percentages have been calculated using total number of clients as the denominator (less not stated/other).

- It is important to note that individual clients beginning support in one housing type need not necessarily be the same individuals ending support in that housing type.

- Not stated/other includes those clients whose housing situation at either the beginning or end of support was unknown.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection. Supplementary table EXIT.4.

Housing outcomes for homeless versus at risk clients

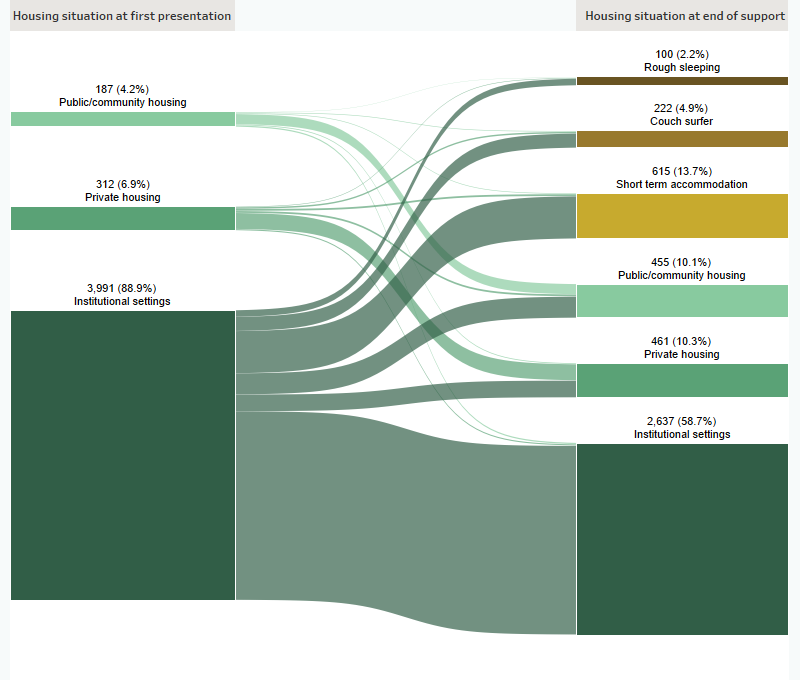

For clients who were at risk of homelessness at the beginning of support and with known housing status at the end of support (almost 4,500 clients), by the end of support (Figure EXIT.1):

- 3 in 5 (59% or over 2,600 clients) remained in institutional settings

- Around 460 clients (10%) were in private housing

- A further 460 clients (10%) were in public or community housing.

- 1 in 5 were known to be homeless at the end of support (almost 940 clients or 21%), many of whom were in institutional settings at the beginning of support (around 870 clients).

Figure EXIT.1: Housing situation for clients exiting custodial arrangements with closed support who began support at risk of homelessness, 2019–20

Notes

- Excludes clients with unknown housing situations.

- Includes only those clients who ceased receiving support during the financial year (meaning that their support period(s) had closed and they were not in ongoing support at the end of the year).

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection, 2019–20

For clients who were known to be homeless at the beginning of support and with known housing status at the end of support (around 1,900 clients), by the end of support, SHS agencies assisted (Interactive Tableau visualisation):

- 1 in 3 (33% or almost 630 clients) into short-term accommodation

- Over 250 (13%) into private housing

- Around 220 clients (12%) into public or community housing.

Around 150 clients (8%) who were known to be homeless at the beginning of support were staying in institutional settings at the end of support.

References

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2012. Children and young people at risk of social exclusion: links between homelessness, child protection and juvenile justice. Cat. no. CSI 13. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2016. Vulnerable young people: interactions across homelessness, youth justice and child protection: 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2015. Cat. no. HOU 279. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019. The health of Australia’s prisoners 2018. Cat. no. PHE 246. Canberra: AIHW.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2019. Prisoners in Australia, 2019. ABS cat. no. 4517.0. Canberra: ABS.

Baldry E, McDonnell D, Maplestone P & Peeters M 2006. Ex-prisoners, homelessness and the State in Australia. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 39(1): 20–33.

Bevitt A, Chigavazira A, Herault N, Johnson G, Moschion J, Scutella R, Tsent Y-P, Wooden M & Kalb G 2015. Journeys Home research report no. 6: complete findings from waves 1 to 6. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research.

CFFR (Council on Federal Financial Relations) 2018. National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. Viewed 9 October 2020.

Cunneen C, Goldson B & Russell S 2016. Juvenile justice, young people and human rights in Australia. Current Issues in Criminal Justice 28(2): 173–189. doi:10.1080/10345329.2016.12036067.

Richards K 2011. Trends in juvenile detention in Australia. Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice 416: 1-8. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Schetzer L & StreetCare 2013. Beyond the prison gates: the experiences of people recently released from prison into homelessness and housing crisis. Sydney: Public Interest Advocacy Centre.

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2020a. Report on Government Services 2020, Part C Table CA.4. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

SCRGSP 2020b. Report on Government Services 2020, Part C, Chapter 8 Table 8A.18. Canberra: Productivity Commission.