Survey of social housing tenants

Tenant experience

The National Social Housing Survey (NSHS) is a national survey that collects information about a range of social housing tenancy experiences across Australia by geography and remoteness. In 2016, the NSHS was conducted across three social housing programs: public housing, state-owned and managed Indigenous housing (SOMIH) and mainstream community housing (Indigenous community housing was out of scope for the 2016 survey).

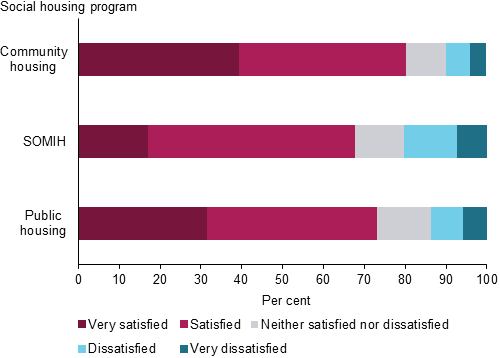

Tenant satisfaction

Tenant satisfaction is defined as the proportion of tenants in social housing who reported they were satisfied or very satisfied with the overall services delivered by their housing provider. In 2016, tenants in community housing were consistently more satisfied with the services delivered by their housing provider (80%) compared with other social housing providers (73% for public rental housing and 68% for SOMIH) (Figure NSHS.1). Satisfaction among SOMIH tenants has risen from 58% in the 2014 survey to 68% in 2016 (see supplementary tables).

Figure NSHS.1: Satisfaction with services provided by housing organisation, by social housing program type, 2016 (per cent)

SOMIH = state-owned and managed Indigenous housing

Source: National Social Housing Survey: A summary of national results 2016. Supplementary Table S1.

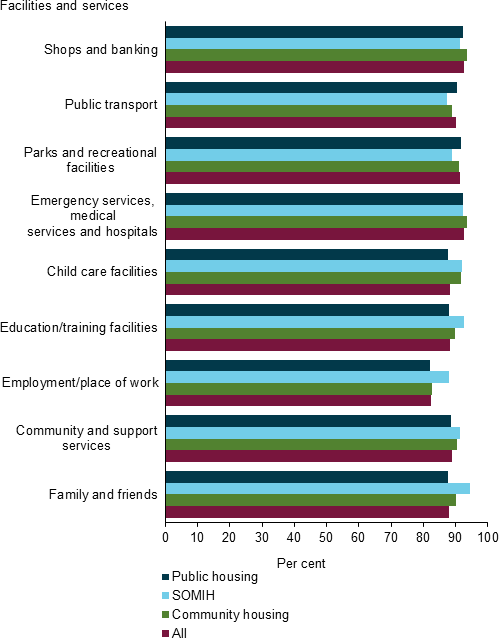

Amenities and location

The amenity component of the NSHS refers to attributes of the dwelling provided such as size, privacy or modifications for special needs whereas the location component relates to the proximity of the dwelling to facilities and services. A high level of satisfaction with social housing amenities and location suggests that the provision of housing assistance was meeting household needs.

Across all programs, respondent satisfaction with the location of their dwelling relative to important services and facilities was high. In particular, proximity to emergency services, medical services and hospitals (95% for public housing, 93% for SOMIH and 95% for community housing) was consistently rated highest in terms of importance and meeting the needs of the household (Figure NSHS.2).

Figure NSHS.2: Location (proximity to facilities and services) rated by tenants as both important and meeting the needs of their households, by social housing program, 2016 (per cent)

SOMIH = state-owned and managed Indigenous housing

Source: National Social Housing Survey: A summary of national results 2016. Supplementary Table S10.

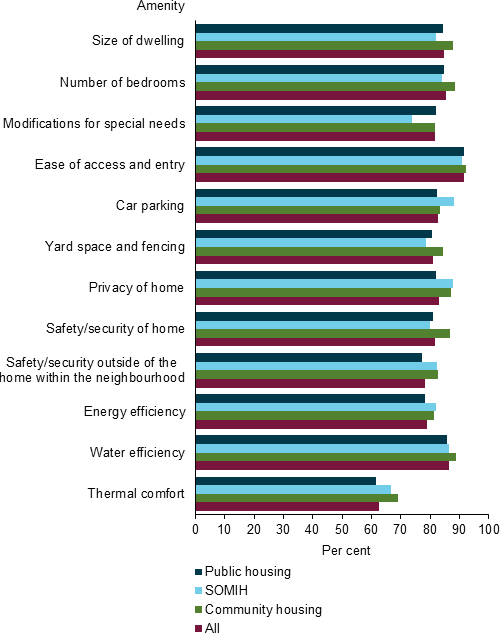

In 2016, NSHS respondents were provided with a list of amenities and asked whether or not they were important to their household and further, whether the selected amenities met the needs of their household. Across all three social housing programs, respondents highly rated ‘ease of access and entry’ to their dwellings as both important and meeting their household needs. On the other hand, despite respondents highly rating ‘thermal comfort’ as important (94% in public housing, 98% in SOMIH and 95% in community housing) this was the least likely to be rated as meeting the household’s needs (62% for public housing, 67% for SOMIH and 69% for community housing) (Figure NSHS.3).

Figure NSHS.3: Amenities rated as both important and meeting their needs by social housing tenants, by social housing program, 2016 (per cent)

SOMIH = state-owned and managed Indigenous housing

Source: National Social Housing Survey: A summary of national results 2016. Supplementary Table S8.

Dwelling standard

In 2016, the NSHS asked social housing tenants about whether their social housing dwelling was of an acceptable standard—defined as having at least four working facilities and not more than two major structural problems.

Of social housing dwellings, respondents reported:

- 80% of public housing dwellings were of an acceptable standard

- 75% of SOMIH dwellings were of an acceptable standard, up from 70% in 2014

- 88% of mainstream community housing dwellings were of an acceptable standard.

Across the social housing programs, respondents in Indigenous households within public rental housing were the least likely to report living in a dwelling of an acceptable standard (66%), when compared with respondents in SOMIH households (75% up from 70% in 2014) and community housing households (77% down from 84% in 2014) (see supplementary tables).

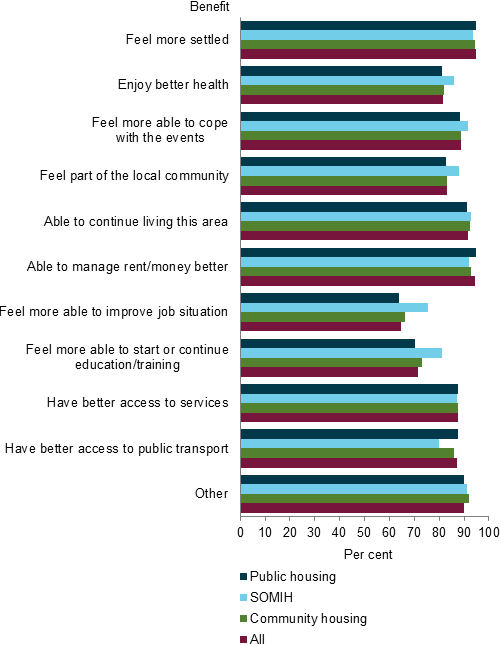

Tenant welfare

Social and economic benefits

Affordable, safe and secure housing can contribute to a range of health and wellbeing outcomes and enhance people’s ability to engage economically and socially in their community. Tenants who reported social and economic participation benefits from living in social housing varied across their individual circumstances and housing programs. Across all social housing programs, 95% of tenants reported they felt ‘more settled’ and 83% felt ‘part of the community’. High proportions reported having better access to services (88%) and were better able to manage their rent/money (95%). In terms of employment and education, a low proportion of social housing tenants felt they were able to improve their job situation (65%) or felt able to start or continue education/training (71%) due to being supported in social housing (Figure NSHS.4).

Figure NSHS.4: Self-reported benefits gained by tenants living in social housing, by social housing program, 2016 (per cent)

SOMIH = state-owned and managed Indigenous housing

Source: National Social Housing Survey 2016. Social housing tenants, Table TENANTS.12.

Educational attainment

The 2016 NSHS found that of all respondents: almost a third (32%) of public housing tenants, two-fifths (40%) of SOMIH tenants, and 29% of community housing tenants reported that their highest level of educational attainment was Year 10 or equivalent. Around 3% of public and community housing respondents reported that they had not completed any formal education compared with only 1% of SOMIH respondents (see supplementary tables).

Just under a third (32%) of NSHS respondents reported their highest level of educational attainment was Year 10 or equivalent.

Comparing the highest level of educational attainment for respondents in the 2016 NSHS to estimates for the general population, aged 15–74 years, illustrates some differences between the two groups.

The proportion for whom Year 12 or equivalent was the highest level of education completed was consistently lower for the 2016 NSHS sample (14% for public rental housing, 11% for SOMIH and 13% for community housing) when compared with the general population aged 15–74 years (18%). Social housing tenants were also less likely to have achieved post year 12 or equivalent qualifications than the general population aged 15–74 years, for example:

- Those in the general population aged 15–74 years were more than twice as likely to have achieved a highest level of education of a Bachelor degree or above (25.7%) than public housing tenants (5%), SOMIH tenants (2%) or community housing tenants (8%).

- The proportion attaining post-secondary school qualifications (that is, certificate, diploma, advanced diploma or bachelor degree or above) in the general population aged 15–74 years (54%) was higher than that for public housing (22%), SOMIH (15%) or community housing (30%), [1].

Employment

To understand employment within social housing, the 2016 NSHS included questions aimed at investigating barriers or disincentives for social housing tenants to either enter the workforce or increase the number of hours worked per week. Tenants who were working part-time, were unemployed or not in the labour force were asked to identify the influences on their current employment status. The top 3 reported reasons were: the need for more training, education or work experience; the desire/need to stay home and look after children; and financial concerns.

The 2016 NSHS further found that between half and three-fifths of all social housing tenants were not in the labour force—that is, they were neither working nor currently looking for work. Conversely, around 39% of public rental housing, 47% of SOMIH and 44% of community housing tenants were in the workforce.

22% of NSHS respondents were employed, either full-time or part-time, in 2016, while more than two-fifths (44%) of respondents were not intending or unable to work.

The provision of social housing and a household’s main source of income may affect work participation decisions for tenants quite differently. At 30 June 2016, more than a quarter of public rental housing households were reported as depending on an age (25%) or disability (29%) pension as their main source of income (data unavailable for SOMIH and community housing). Employment disincentives for social housing tenants may also include—rent increases as a result of increased income; social housing ineligibility where their income exceeds a certain threshold; as well as a potential lack of social housing availability in areas with increased employment prospects. Alternatively, social housing may afford tenants with greater stability, increasing their opportunities to find and maintain suitable employment [3].

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2016. Education and Work, 2016. ABS cat no. 6227.0, Canberra: ABS.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2017. National Social Housing Survey: a summary of national results 2016. Cat. no. HOU 288. Canberra: AIHW.

- PC (Productivity Commission) 2015. Housing Assistance and Employment in Australia. Commission Research Paper. Canberra: PC.