Cannabis

Key findings

View the Cannabis in Australia fact sheet >

The 2 most common subspecies within the cannabis genus from which cannabis is harvested are Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica. Cannabis comes in 3 main forms:

- Herbal cannabis (also referred to as marijuana) – the dried leaves and flowers of the cannabis plant (the weakest form)

- Cannabis resin (hashish) – the dried resin from the cannabis plant

- Cannabis oil (hashish oil) – the oil extracted from the resin (the strongest form) (ACIC 2021a; NSW Ministry of Health 2017).

Cannabis is most commonly smoked in a rolled cigarette (joint) or water pipe, often in combination with tobacco, but it may also be added to food and eaten. Cannabis oil is generally applied to cannabis herb or tobacco and smoked, or heated and the vapours inhaled (ACIC 2021a).

The main psychoactive component of the cannabis plant is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). THC is highest in the flowering tops and leaves of the plant. Other than THC, cannabis has more than 70 unique chemicals that are collectively referred to as cannabinoids (ACIC 2018). Cannabis is a central nervous system depressant, but also alters sensory perceptions and may produce hallucinogenic effects when large quantities are used (ACIC 2018; NSW Ministry of Health 2017). The use of cannabis for medicinal purposes was legislated by the Australian parliament in 2016.

Synthetic cannabinoids are a new psychoactive substance that was originally designed to mimic or produce similar effects to cannabis (Alcohol & Drug Foundation 2017). The availability, consumption and harms associated with synthetic cannabis are discussed further in the section on new (and emerging) psychoactive substances (NPS).

Availability

Cannabis is relatively easy to obtain in Australia. Most participants in the Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) and the Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) report that cannabis is perceived as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to obtain. This has remained relatively stable over time, as has perceived purity and pricing (Sutherland et al. 2023b; Sutherland et al. 2023a).

Perceived availability was the highest for hydroponic cannabis (90% of 2023 IDRS participants and 96% of 2023 EDRS participants rated it ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to obtain), followed by bush cannabis (78% of 2023 IDRS participants and 95% of 2023 EDRS participants perceived it ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to obtain) (Sutherland et al. 2023b; Sutherland et al. 2023a).

Data collection for 2023 took place from April–July for the EDRS and June–July for the IDRS. Changes due to the impacts of COVID-19 resulted in EDRS and IDRS interviews in 2020–2023 being delivered face-to-face as well as via telephone and videoconference. All interviews prior to 2020 were delivered face-to-face, this change in methodology should be considered when comparing data from the 2020–2023 samples relative to previous years.

According to the 2022–2023 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS), people aged 14 years and over who had recently used cannabis reported their usual source as:

- friends (61%)

- dealers (21%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.35).

The Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC) collects national illicit drug seizure data annually from federal, state and territory police services, including the number and weight of seizures to inform the Illicit Drug Data Report (IDDR).

According to the latest IDDR, in 2020–21, half (52%) of all national illicit drug seizures were for cannabis. However, cannabis only accounted for around a quarter (26%) of the weight of illicit drugs seized nationally.

The number and weight of national cannabis seizures has increased over the last decade:

- The number of seizures increased from 51,823 in 2011–12 to 55,199 in 2020–21.

- The weight seized increased from 7,349 kilograms in 2011–12 to a record 10,787 kilograms in 2020–21 (ACIC 2023, Figure 12).

The number and weight of detections of cannabis at the Australian border has fluctuated over the last decade with an overall increase:

- The number of detections increased between 2019–20 and 2020–21 by 89% (12,846 and 24,255, respectively) and increased by 812% since 2011–12 (2,660 detections).

- The weight of cannabis detected at the Australian border increased from 17 kilograms in 2011–12 to 648 kilograms in 2019–20 before increasing to 819 kilograms in 2020–21 (ACIC, Figure 10).

Consumption

For related content on cannabis consumption by region, see also:

Cannabis continues to be the world’s most widely used illicit drug; 4.3% of the global population aged 15–64 years (or approximately 219 million people) reported using cannabis at least once in 2021 (UNODC 2023).

In 2021, the proportion of people aged 15–64 in Australia and New Zealand that had consumed cannabis at least once was higher (12.1%) than the global average of 4.3% (UNODC 2023).

The 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that cannabis continues to have the highest reported prevalence of lifetime and recent consumption among the Australian population, compared with other illicit drugs (AIHW 2024b, tables 5.2 & 5.6). For people aged 14 and over in 2022–2023:

- 41% had used cannabis in their lifetime and 11.5% had used cannabis in the previous 12 months (Figure CANNABIS1).

- The lifetime use of cannabis has increased from 33% in 2001 while recent use of cannabis has decreased from 12.9%.

- Daily cannabis use has increased from 14% in 2019 to 18% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, tables 5.2, 5.6 & 5.33).

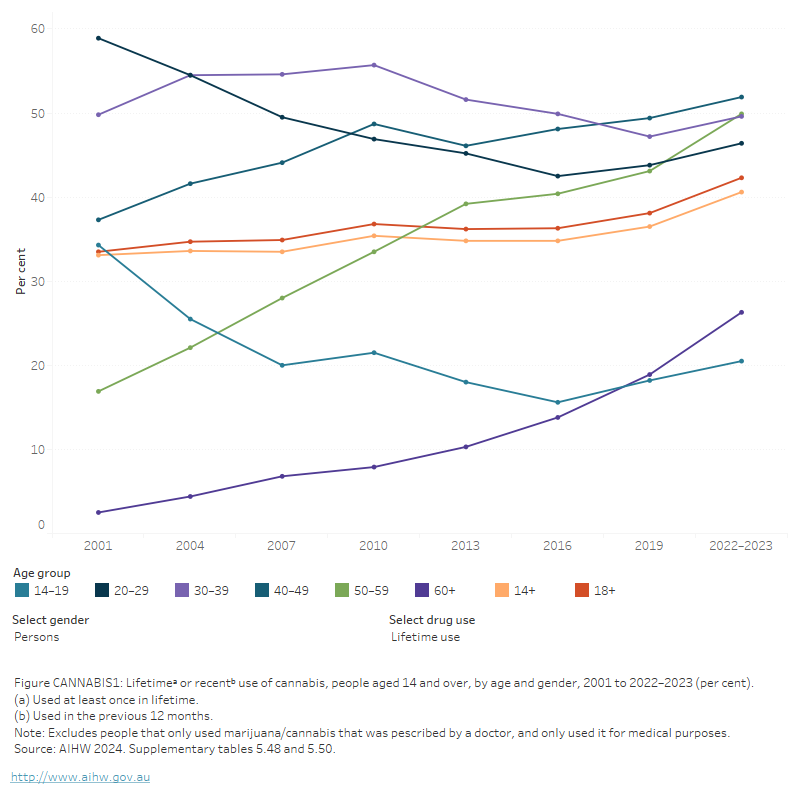

Figure CANNABIS1: Lifetimeᵃ or recentᵇ use of cannabis, people aged 14 and over, by age and gender, 2001 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

The figure shows the proportion of people who recently used cannabis by age group between 2001 and 2019. Between 2001 and 2019, there were decreases in the proportion of people aged 14–19 (from 24.6% to 13.3%) and 20–29 (from 29.3% to 23.8%) who used recently used cannabis. Over the same period, there were increases in the proportion of people aged 50–59 who recently used cannabis (from 3.3% to 9.2%). In 2019, people aged 20–29 (23.8%) and 30–39 (13.7%) were most likely to have recently used cannabis.

View data tables >

Cannabis use by age and gender

The NDSHS has found recent cannabis use has declined among the younger age groups (those aged 14–39) but has increased for the older age groups (40 or over).

- Compared with those in other age groups, people aged 20–29 continue to be the most likely to use cannabis, but this declined from 29% in 2001 to 23% in 2022–2023.

- Males aged 14 and over were more likely to have recently used cannabis (13.1%) than females (9.8%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.50).

Cannabis is used more frequently than other drugs such as ecstasy and cocaine. Specifically, 21% of people who used cannabis did so as often as weekly or more, compared with only *2.2% and 3.2% of ecstasy and cocaine users respectively. Males were more likely than females to use cannabis weekly (22% compared with 19%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.33).

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

Geographic trends

The 2022–2023 NDSHS found little change in the proportion of recent cannabis use between 2019 and 2022–2023 for all states and territories. The Northern Territory had the highest proportion of recent cannabis use (18.9%) while the Australian Capital Territory had the lowest proportion (8.7%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 9a.11).

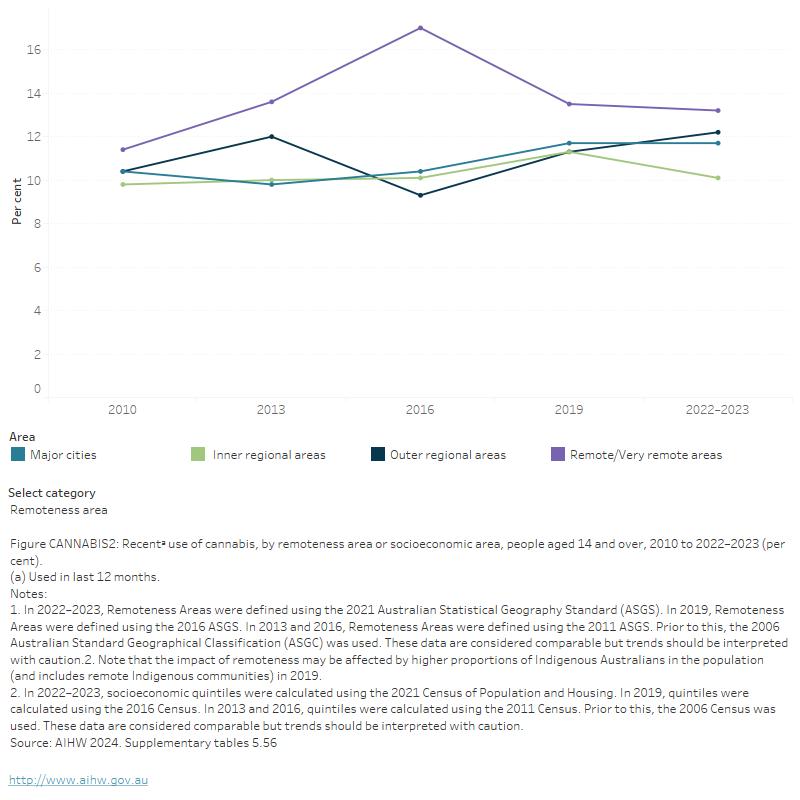

People living in Remote and very remote areas were more likely than those living in Major cities to have used cannabis in the previous 12 months (13.2% and 11.7% respectively). Between 2019 and 2022–2023, recent use of cannabis:

- decreased in Inner regional areas (11.3% to 10.1%)

- increased in Outer regional areas (11.3% to 12.2%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 9a.12).

People living in areas of the highest socioeconomic advantage were more likely to have used cannabis in the previous 12 months (13.1%) than those living in the most disadvantaged areas (11.6%) (Figure CANNABIS2; AIHW 2024b, Table 9a.14).

Figure CANNABIS2: Recenta use of cannabis, by remoteness area or socioeconomic area, people aged 14 and over, 2010 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

The figure shows the proportion of recent cannabis use for people aged 14 and over by socioeconomic area for 2010, 2013, 2016 and 2019. Recent cannabis use trends were fairly stable across all 5 socioeconomic areas between 2010 and 2019. In 2019, regardless of what socioeconomic area a person came from, about 1 in 10 had recently used cannabis (12.6% of most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas and 12.4% of most advantaged socioeconomic areas).

The National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program (NWDMP) measures the presence of substances in sewerage treatment plants across Australia. It should be noted that wastewater analysis cannot differentiate between prescribed and illicit use. For further information, see Box HARM2 and Data quality for the National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program.

Data from report 21 of the NWDMP indicate:

- Cannabis was the most consumed illicit drug in Australia, followed by methylamphetamine.

- That the estimated population-weighted average consumption of cannabis in regional areas was higher than in capital cities in August 2023 (ACIC 2024).

For state and territory data, see the National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program reports.

Medicinal cannabis

Box CANNABIS1: What is medical cannabis?

Medical cannabis generally refers to medical products that contain Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or Cannabidiol (CBD) (Healthdirect 2022). Access to medical cannabis was legalised in Australia in 2016 and went through substantial changes in 2021. These changes were designed to improve accessibility, by making it easier for prescribers to be authorised to prescribe medical cannabis, and making it easier for patients to change to different medical cannabis products (NPS MedicineWise 2022).

Medical cannabis typically refers to use of cannabis that is prescribed by a healthcare professional. However, in the 2022–2023 National Drug Strategy Household Survey, use includes that where a respondent received a diagnosis and prescription from a medical professional, as well as cases where the respondent has used cannabis for self-determined medical purposes.

In 2022–2023, the NDSHS found 3.0% of people aged 14 and over in Australia reported using cannabis for medical purposes in the previous 12 months. One in 3 of them (or 1.0% nationally) had used cannabis exclusively for medical purposes, an increase from 0.8% in 2019 (AIHW 2024b, Table 8.1). Additionally, of people aged 14 and over who had used cannabis in the previous 12 months:

- 22% were always prescribed by a doctor, an increase from 1.8% in 2019 (AIHW 2024b, Table 8.3), potentially reflecting better accessibility to medical cannabis prescriptions.

- 48% reported being diagnosed or treated for chronic pain (AIHW 2024b, Table 8.7).

- Of those who used cannabis only for medical purposes, and were prescribed by a doctor, 64% used medical cannabis products (for example, pharmaceutical CBD/THC oil) (AIHW 2024b, Table 8.9).

Compared with people who did not use cannabis for medical purposes, people who had recently used cannabis for medical purposes only (and were prescribed by a doctor) were:

- Typically, older (39% aged 50 and over) than people who used cannabis non-medically (18%)

- More likely to live in Major city areas (63%) than Outer regional (15.3%) or Remote and very remote areas (*2.4%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 8.6).

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

Poly drug use

Poly drug use is defined as the use of mixing or taking another illicit or licit drug whilst under the influence of another drug. Cannabis use is also highly correlated with the use of tobacco, alcohol and other drugs. This makes measuring the effects of cannabis alone difficult and potentially increases risks for users.

The NDSHS showed that the use of other drugs and cannabis declined across all reported drug types between 2019 and 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.61).

The most common other drugs concurrently used by recent cannabis users were:

- Alcohol (74%)

- Tobacco (41%)

- Cocaine (11.4%)

- Ecstasy (10.5%)

- Hallucinogens (9.9%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.61)

Analysis of NDSHS data indicated that poly drug use varied among different population groups:

- Males were more likely than females to have used alcohol, tobacco, or any illicit drug at the same time as cannabis in 2022–23.

- People in their 50s were more likely than those in other age groups to have used cannabis at the same time as alcohol or tobacco, while those in their 20s were the most likely to have used it with an illicit drug.

- People in Remote and very remote areas were the most likely to use alcohol (79%) or tobacco (51%) at the same time as cannabis, while those in Major cities were the most likely to report using illicit drugs (24%) or not using other drugs (20%) with cannabis (AIHW 2024b, Tables 2.10–2.12).

Data on alcohol and other drug-related ambulance attendances are sourced from the National Ambulance Surveillance System (NASS). Monthly data for 2021 and 2022 are currently available for New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. It should be noted that some data for Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory have been suppressed due to low numbers. Please see the data quality statement for further information.

In 2022, the proportion of cannabis-related ambulance attendances where multiple drugs were involved (excluding alcohol) ranged from 39% of attendances in Tasmania to 49% of attendances in Victoria (Table S1.11).

For related content on multiple drug involvement see Impacts: Ambulance attendances.

Harms

For related content on cannabis impacts and harms, see also:

The effects of cannabis (like all drugs) vary from one person to another including, but not limited to, the amount consumed, the mode of administration, the user’s previous experience, mood and body weight (NSW Ministry of Health 2017). The active drug in cannabis makes its way into the bloodstream more quickly when cannabis is smoked, compared to when it is orally ingested. Ongoing and regular use of cannabis is associated with a number of negative long-term effects. Regular users of cannabis can become dependent and commonly reported symptoms of withdrawal include anxiety, sleep difficulties, appetite disturbance and depression (Hall & Degenhardt 2009; Nielsen & Gisev 2017).

An overview of some of the short and long-term effects of cannabis are provided in Table CANNABIS1.

| Short-term effects | Long-term effects |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: Adapted from (Hall & Degenhardt 2009; Nielsen & Gisev 2017; NSW Ministry of Health 2017).

Burden of disease and injury

The Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018, found that cannabis use contributed to 0.3% of the total burden of disease and injuries in 2018 and 10.2% of the total burden due to illicit drugs (AIHW 2021b; Table S2.5). Drug use disorders (excluding alcohol) (11%) contributed most to the burden due to cannabis use, followed by poisoning (10%). Only a small proportion (3% or less) of the burden of schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, road traffic injuries and depressive disorders was attributable to cannabis use (AIHW 2021).

Ambulance attendances

Data on alcohol and other drug-related ambulance attendances are sourced from the National Ambulance Surveillance System (NASS). Monthly data are presented from 2021 for people aged 15 years and over for New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory.

For the 6 jurisdictions where alcohol intoxication-related ambulance attendances data are available, in 2022:

- Rates of attendances ranged from 76.7 per 100,000 population (4,167 attendances) in Victoria to 348.0 per 100,000 population (688 attendances) in Northern Territory.

For the 5 jurisdictions where alcohol and other drug-related ambulance attendance data are available for age and sex disaggregation (New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory):

- 3 in 5 (60%) of total attendances were for males.

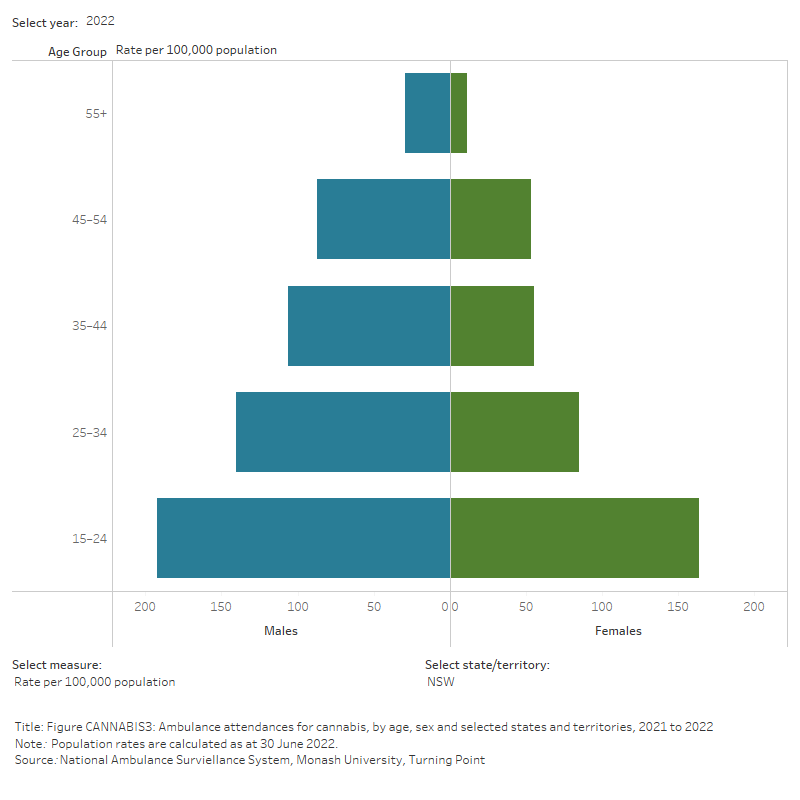

- Ambulance attendances for cannabis are typically a younger cohort of people, with the highest rates of attendances in people aged 15–24.

- Rates of attendance for people aged 15-24 ranged from:

For the 6 jurisdictions where monthly data from 2021 is available, between 2021 and 2022:

- Rates of cannabis-related ambulance attendances have decreased across all jurisdictions, with the exception of Queensland, Tasmania and the Northern Territory.

- In Queensland, Tasmania and the Northern Territory, cannabis-related ambulance attendance rates have increased from 2021 to 2022 (101.9 to 108.7 per 100,000 population in Queensland, 127.5 to 137.2 per 100,000 population Tasmania and 334.1 to 348.0 per 100,000 population in Northern Territory) (Table 1.10).

Figure CANNABIS3: Ambulance attendances for cannabis, by age, sex and selected states and territories, 2021 to 2022

This figure shows cannabis-related ambulance attendances in NSW. The highest number of attendances were for males aged 15-24. There is a filter to select year, state/territory, drug and measure (number of attendances or rate per 100,000 population).

Hospitalisations

Drug-related hospitalisations are defined as hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis relating to a substance use disorder or direct harm relating to use of selected substances (AIHW 2018).

AIHW analysis of the National Hospital Morbidity Database showed that cannabinoids (including cannabis) accounted for around 1 in 20 drug-related hospitalisations in 2021–22 (5.1% or 6,900 hospitalisations). This represents a rate of 26.6 cannabinoid-related hospitalisations per 100,000 population (Table S1.12c).

In 2021–22:

- Almost 2 in 3 cannabinoid-related hospitalisations involved an overnight stay (64% or 4,400 hospitalisations), while the remainder ended with a same-day discharge.

- Males were more likely than females to be hospitalised; almost 2 in 3 cannabinoid-related hospitalisations (62% or 4,200 hospitalisations)

- Over 1 in 3 cannabinoid-related hospitalisations were people aged 15–24 years old (35% or 2,400 hospitalisations) (Table S1.12a–12c).

- Over 2 in 3 cannabinoid-related hospitalisations occurred in Major cities (69% or 4,700 hospitalisations).

- When accounting for differences in population size, the rate of hospitalisations was highest in Remote and very remote areas (69.7 hospitalisations per 100,000 population, compared with 25.6 per 100,000 in Major cities) (Table S1.14).

In the 7 years to 2021–22:

- The number of hospitalisations for cannabinoids increased between 2015–16 and 2021–22 (from 6,000 to 6,900 hospitalisations), peaking at 7,500 in 2020–21.

- Accounting for population growth, the rate of cannabinoid-related hospitalisations was relatively stable between 2016–17 and 2020–21 at about 24-27 hospitalisations per 100,000 people. The only deviation was in 2020–21 when it peaked at 29.2 per 100,000 population.

- The rate of cannabinoids-related hospitalisations was highest in Remote and Very remote areas and increased from 2015–16 (41.0 per 100,000) to 2021–22 (69.7 per 100,000), peaking in 2019–20 (76.1 per 100,000) (Table S1.14; Figure IMPACT5).

Population estimates used to calculate rates for 2020–21 may have been impacted by public health measures introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. See the Technical notes for more information.

Deaths

Drug-induced deaths are determined by toxicology and pathology reports and are defined as those deaths that can be directly attributable to drug use. This includes deaths due to acute toxicity (for example, drug overdose) and chronic use (for example, drug-induced cardiac conditions) (ABS 2021).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) analysis of the AIHW National Mortality Database showed that in 2022, cannabinoids were present in 3.4% (or 57) of all drug-induced deaths, a decrease from 4.5% (80 deaths) in 2021 (Table S1.1).

The short-term effects of cannabis can increase the risk of road traffic crashes, largely due to diminished driving performance in response to emergencies (Hall & Degenhardt 2009). In 2016, cannabis was the second most common drug identified on toxicology for transport accidents where a drug (excluding alcohol) contributed to death (ABS 2017).

Treatment

The latest Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia: early insights report shows that cannabis was the third most common principal drug of concern in 2022–23, representing 17% of treatment episodes provided to clients for their own drug use (AIHW 2024a). This is down from 19% in 2021–22. This represents a rate of 115 clients and 178 episodes per 100,000 population in 2021–22, down from a peak of 153 clients and 216 episodes per 100,000 in 2015–16 (AIHW 2024c, Table 3.1).

Data collected for the AODTS NMDS are released twice each year: an early insights report in April and a detailed report mid-year. The section below will be updated with information from the annual report once these data become available.

The AODTS NMDS provides information on treatment provided to clients by publicly funded AOD treatment services, including government and non-government organisations.

In 2021–22, where cannabis was the principal drug of concern:

- Over 3 in 5 (62%) of clients were male and 1 in 5 (20%) were Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2023, tables SC.9 and SC.11).

- Two-thirds (66%) of clients were aged 10–29 (AIHW 2023, Table SC.10).

- The most common source of referral was a health service and self/family (both 29% of treatment episodes), followed by diversion from the criminal justice system (20%) (AIHW 2023, Table Drg.28).

- Counselling was the most common main treatment type (47% of treatment episodes), followed by assessment only (16%) (AIHW 2023, Table Drg.27; Figure CANNABIS4).

- The median treatment duration for cannabis was 26 days (AIHW 2023, Table Drg.30).

Figure CANNABIS4: Treatment provided for own use of cannabis, 2021–22

Cannabis was the 3rd most common principal drug of concern (19% of treatment episodes)

Almost 1 in 5 clients were Indigenous Australians

Counselling was the most common main treatment type (almost 1 in 2 episodes)

Source: AIHW 2023, tables Drg.1, SC.11 and Drg.27.

Where the most common drug of concern was cannabis, the proportion of people living in Regional and remote areas who travelled 1 hour or longer to treatment services was higher than in Major cities (25% compared with 7%) (AIHW 2019).

Longitudinal analysis of AODTS NMDS data has indicated that over 221,000 clients received treatment for their own use of cannabis between 2013–14 and 2021–22 (AIHW 2024c). Additionally:

- Almost 3 in 4 clients (71%) received treatment for cannabis only, while the remainder also received treatment for another drug (such as alcohol or amphetamines).

- Around 605,000 treatment episodes were provided to these clients, mostly for clients who sought treatment for cannabis and another drug (67%).

- Almost half (48%) of all clients were referred to treatment via a drug diversion program on at least one occasion between 2013–14 and 2021–22 (AIHW 2024c).

Clients who received treatment for cannabis and another principal drug of concern had many more unique treatment pathways than clients who received treatment for cannabis only.

At-risk groups

For related content on at-risk groups, see:

The use of cannabis can be disproportionately higher for specific population groups.

- Marijuana, hashish or cannabis resin is the most commonly reported illicit drug used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- The highest recorded number of arrests were those relating to cannabis and high proportions of police detainees and prison entrants recently used cannabis.

- Cannabis is the most commonly used illicit substance among adolescents aged 12–17.

- Cannabis is the most frequently used illicit drug for people who inject drugs.

Policy context

Public perceptions and policy support

There have been changes over time in public perceptions of cannabis use in Australia. Data from the 2022–2023 NDSHS showed:

- 12.9% of Australians reported cannabis as the first drug they thought of when asked about a drug problem.

- Personal approval of cannabis use by an adult increased from 19.6% in 2019 to 23.4% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, tables 11.1 and 11.7).

There have also been some associated changes in public perceptions about cannabis-related policies. For example:

- The majority of Australians aged 14 years and over (80%) do not support the possession of cannabis being a criminal offence, which is higher than the 78% reported in 2019 (AIHW 2024b, Table 11.15).

Resources and further information

Information about the medicinal use of cannabis in Australia can be found at the Office of Drug Control.

Alcohol and Drug Foundation (2017). Synthetic cannabinoids, accessed 30 November 2017.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2017). Causes of Death, Australia 2016. ABS cat. no. 3303.0. Canberra: ABS, accessed 4 January 2019

ABS (2019). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018–19. ABS cat. no. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS, accessed 8 January 2020.

ACIC (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission) (2018). Illicit Drug Data Report 2016–17. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 21 September 2018.

ACIC (2021). Illicit Drug Data Report 2019–20. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 22 October 2021.

ACIC (2022). National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program Report 15. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 18 March 2022.

ACIC (2023). Illicit Drug Data Report 2020–21. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 23 October 2023.

ACIC (2024) National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program Report 21. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 14 March 2024.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2018). Drug related hospitalisations. Cat. no. HSE 220. Canberra: AIHW, accessed 18 August 2021.

AIHW (2019). Alcohol and other drug use in regional and remote Australia: consumption, harms and access to treatment, 2016–17. Cat. no. HSE 212. Canberra: AIHW, accessed 15 March 2019.

AIHW 2021. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018, AIHW, Australian Government.

AIHW (2023). Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services annual report. Cat. No. HSE 250. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 21 June 2023.

AIHW (2024a) Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia: early insights. AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 16 April 2024.

AIHW (2024b). National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023. AIHW, accessed 22 February 2024.

AIHW (2024c). Trends in cannabis availability, use, and treatment in Australia, 2013–14 to 2021–22. AIHW, accessed 19 April 2024.

Hall W & Degenhardt L (2009).Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 374: 1383-1391.

Healthdirect (2022) Medicinal cannabis, healthdirect website, accessed 17 October 2023.

Nielsen S & Gisev N (2017). Drug pharmacology and pharmacotherapy treatments. In Ritter, King and Lee (eds). Drug use in Australian society. 2nd edn. Oxford University Press.

National Prescribing Service (NPS) MedicineWise (2022) ‘Unapproved’ medicinal cannabis: changes to prescribing pathway, NPS MedicineWise website, accessed 17 October 2023.

NSW Ministry of Health (2017). A quick guide to drugs & alcohol, 3rd edn. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.

Sutherland R, Karlsson A, King C, Uporova J, Chandrasena U, Jones F, Gibbs D, Price O, Dietze P, Lenton S, Salom C, Bruno R, Wilson J, Grigg J, Daly C, Thomas N, Radke S, Stafford L, Degenhardt L, Farrell M, & Peacock A (2023a). Australian Drug Trends 2023: Key Findings from the National Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) Interviews. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney. Accessed 25 October 2023.

Sutherland R, Uporova J, King C, Chandrasena U, Karlsson A, Jones F, Gibbs D, Price O, Dietze P, Lenton S, Salom C, Bruno R, Wilson J, Agramunt S, Daly C, Thomas N, Radke S, Stafford L, Degenhardt L, Farrell M, & Peacock A (2023b). Australian Drug Trends 2023: Key Findings from the National Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) Interviews. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney. Accessed 25 October 2023

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) (2023). World Drug Report 2023. Vienna: UNODC, accessed 25 October 2023.