Illicit opioids, including heroin

Key findings

Opioids refer to a class of drugs that include those that are derived from the opium poppy and those that are semi or fully synthetic (ACIC 2019; NSW Ministry of Health 2017). Diacetylmorphine, commonly known as heroin, is a derivative of morphine, an alkaloid contained in raw opium (ACIC 2021a).

This section focuses on the harms, availability and consumption of illicit opioids including heroin, as distinct from pharmaceutical opioids such as morphine, methadone and oxycodone. See the section on pharmaceuticals for recent trends and data in relation to the use and harms for pharmaceutical opioids.

Availability

The availability of heroin in Australia has fluctuated over time. In the early 2000s, there was a rapid and considerable reduction in the availability of heroin in Australia (commonly referred to as the heroin shortage or drought) and this was associated dramatic reductions in heroin-related overdoses (Degenhardt et al. 2004). Since then, the availability of heroin has steadily increased.

Prior to COVID-19 in 2020, the Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) showed no significant changes in the pricing, perceived availability. and perceived purity of heroin in Australia, as reported by people who inject drugs (Peacock et al. 2019).

In 2023, the reported median price of heroin was $350 for one gram, stable relative to $400 for one gram 2022. There were changes in the perceived purity and perceived availability of heroin. More specifically, in 2023:

- The proportion of people who believed heroin was ‘very easy’ to obtain increased to 56% from 43% in 2022.

- Fewer participants perceived heroin as being ‘difficult’ to obtain (7%, compared to 11% in 2022).

- Nearly 3 in 10 (28%) participants perceived the purity of heroin as ‘high’, stable relative to 2022 (29%). The proportion of participants that perceived the purity of heroin as ‘low’ remained stable (25%) relative to 2022 (26%) (Sutherland et al. 2023b).

Data collection for 2023 took place in June and July. Changes due to the impacts of COVID-19 resulted in IDRS interviews in 2020–2023 being delivered face-to-face as well as via telephone and videoconference. All interviews prior to 2020 were delivered face-to-face, this change in methodology should be considered when comparing data from the 2020–2023 samples relative to previous years (Sutherland et al. 2023b).

The Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC) collects national illicit drug seizure data annually from federal, state and territory police services, including the number and weight of seizures to inform the Illicit Drug Data Report (IDDR). The number of heroin detections at the Australian border has fluctuated over the past decade. Between 2011–12 and 2020–21:

- The number of heroin detections at the Australian border increased from 179 in 2011–12 to a record 622 detections in 2020–21 (an increase of 247%).

- The weight of heroin detected increased from 256 kilograms in 2011–12 to 1,247 kilograms in 2020–21 (an increase of 387%).

- The number of national heroin seizures increased from 1,758 up to 2,130 seizures.

- The weight of heroin seized increased from 388 kilograms to a record 1,278 kilograms (ACIC 2023).

Consumption

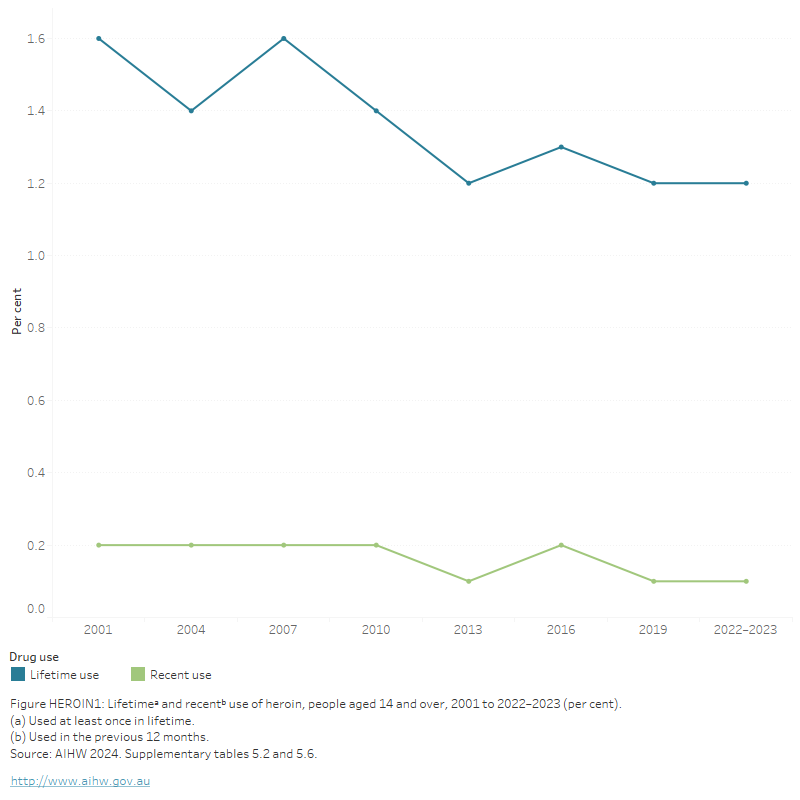

The National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) shows that heroin use among the general population has remained low in Australia between 2001 (0.2%) and 2022–2023 (*0.1%) (Figure HEROIN1, AIHW 2024b, Table 5.6). In 2022–2023, 8.0% of people reported heroin to be the drug of most concern to the community and 11.6% thought it caused the most deaths (AIHW 2024b, tables 11.5 and 11.3).

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

Figure HEROIN1: Lifetimea and recentb use of heroin, people aged 14 and over, 2001 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

This figure shows the proportion of lifetime and recent use of heroin for people aged 14 and over between 2001 and 2019. In 2019, only 0.1% of people aged 14 and over reported using heroin in the last 12 months and this has remained stable since 2001. Lifetime use of heroin has been decreasing since 2007, from 1.6% to 1.2% of people aged 14 and over.

View data tables >

Geographic trends

The National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program (NWDMP) indicates that heroin consumption in Australia is relatively low but has fluctuated over time. The estimated weight of heroin consumed peaked at 1,077 kilograms in 2021–22, before decreasing to 999 kilograms in 2022–23 (ACIC 2024; Figure HEROIN2).

Data from Report 21 of the NWDMP show that nationally:

- Between April and August 2023, the population-estimated average consumption of heroin increased in both capital city and regional sites.

- In August 2023, heroin consumption in capital cities exceeded consumption in regional areas (ACIC 2024).

For state and territory data, see the National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program reports.

Figure HEROIN2: Estimated consumption of heroin in Australia based on detections in wastewater, 2021 to 2023

Australians consumed an estimated 999 kg of heroin in 2022–23

Heroin consumption is typically higher in capital cities than regional areas

Between April and August 2023, average consumptionᵃ of heroin increased in both capital cities and regional areas

(a) “Average consumption” refers to estimated population-weighted average consumption.

Note: Report 21 covers 57% of the Australian population (62 wastewater treatment sites)

Source: AIHW. Adapted from ACIC 2024.

Poly drug use

Heroin

Data on alcohol and other drug-related ambulance attendances are sourced from the National Ambulance Surveillance System (NASS). Monthly data from 2022 are currently available for New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. It should be noted that some data for Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory have been suppressed due to low numbers. Please see the data quality statement for further information.

In 2022, multiple drugs (excluding alcohol) were involved in at least 3 in 10 heroin-related ambulance attendances, ranging from 36% in Victoria to 44% in Queensland (Table S1.11).

For related content on Multiple drug involvement see Impacts: Ambulance attendances.

Harms

For related content on illicit opioid (including heroin) impacts and harms, see also:

Heroin is a central nervous system depressant. Like other opioids, it binds to receptors in the brain, sending signals to block pain and slow breathing.

Heroin may be snorted, swallowed or smoked, but is most commonly melted from a powder or rock form and injected. Injection comes with a range of additional harms associated with the unsanitary sharing of injecting equipment, such as the transmission of blood borne viruses like Hepatitis C and HIV (Table HEROIN1).

| Short-term effects | Long-term effects |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: Adapted from ACIC 2019a; Nielsen & Gisev 2017; NSW Ministry of Health 2017.

Burden of disease and injury

The Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018 found that opioid use was responsible for 0.9% of the total burden of disease and injuries in Australia in 2018 and 32% of the total burden due to illicit drug use (Table S2.5).

Most of the burden due to opioid use was due to 2 linked diseases: poisoning and drug use disorders (excluding alcohol). Poisoning contributed to 42%, and drug use disorders (excluding alcohol) to 28%, of the total burden due to opioid use. A further 2.9% of the burden due to opioid use was attributable to suicide and self-inflicted injuries (AIHW 2022b).

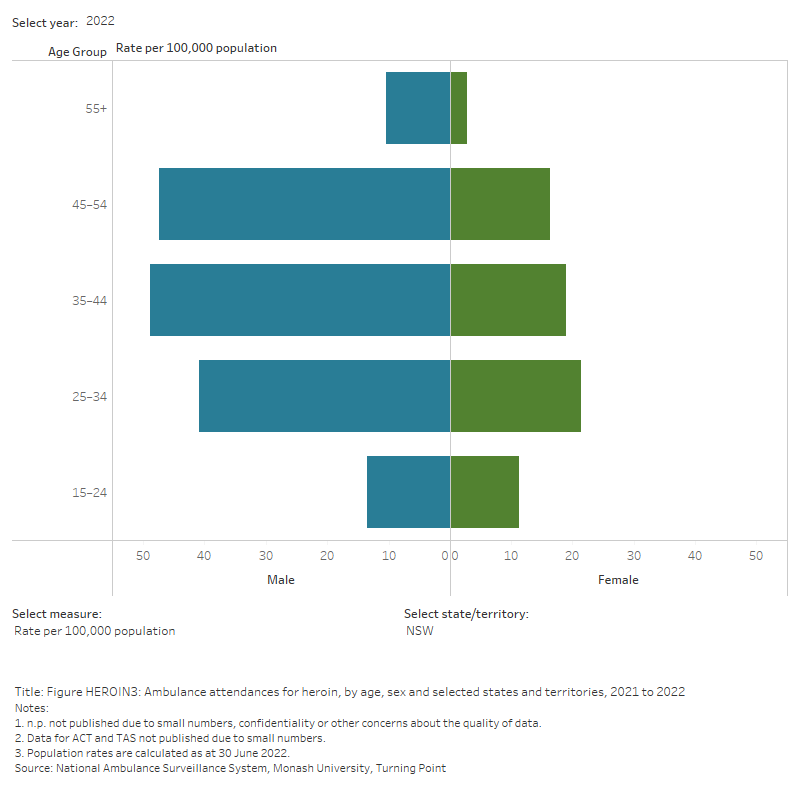

Ambulance attendances

Data on alcohol and other drug-related ambulance attendances are sourced from the National Ambulance Surveillance System (NASS). Monthly data are presented from 2021 for people aged 15 years and over for New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory, and the Northern Territory. Attendance numbers for Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory are reported at the total state level due to small numbers in other categories.

For the 6 jurisdictions where heroin-related ambulance attendances data are available, in 2022:

- Rates of attendances ranged from 2.1 per 100,000 population in Tasmania to 43.2 per 100,000 population in Victoria.

In 2022, for heroin-related ambulance attendances in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland:

- 7 in 10 (72%) of attendances were for males.

- Rates of attendance are typically higher in the older age groups. The highest rates of attendances were in people aged 35–44, in:

- Victoria (837 attendances, 88.4 per 100,000 population).

- New South Wales (380 attendances, 33.9 per 100,000 population).

- Queensland (152 attendances, 21.3 per 100,000 population) (Table S1.10).

For the 5 jurisdictions where monthly data from 2021 is available, between 2021 and 2022:

- Rates of heroin-related ambulance attendances have increased across all jurisdictions, with the exception of Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory where they remained stable.

Figure HEROIN3: Ambulance attendances for heroin, by age, sex and selected states and territories, 2021 to 2022

This figure shows heroin-related ambulance attendances in NSW. The highest number of attendances were for males aged 35-44. There is a filter to select year, state/territory, drug and measure (number of attendances or rate per 100,000 population).

Hospitalisations

Opioid poisoning can result in significant harm, including respiratory failure, aspiration, hypothermia and death.

In 2018–19, drug-related hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of opioid poisoning were more likely to involve pharmaceutical opioids than heroin.

- Nearly half (46%) were due to natural and semi-synthetic opioids, 16% to synthetic opioids and methadone accounted for 7%.

- Heroin accounted for 1 in 4 (25%) (Man et al. 2021).

The age-standardised rate of hospitalisations due to heroin poisoning increased from 3.2 per 100,000 in 2017–18 to 4.1 in 2018–19. Over the same period, the rate of hospitalisations due to natural and semi-synthetic opioids decreased from 8.1 to 7 per 100,000 population (Man et al. 2021).

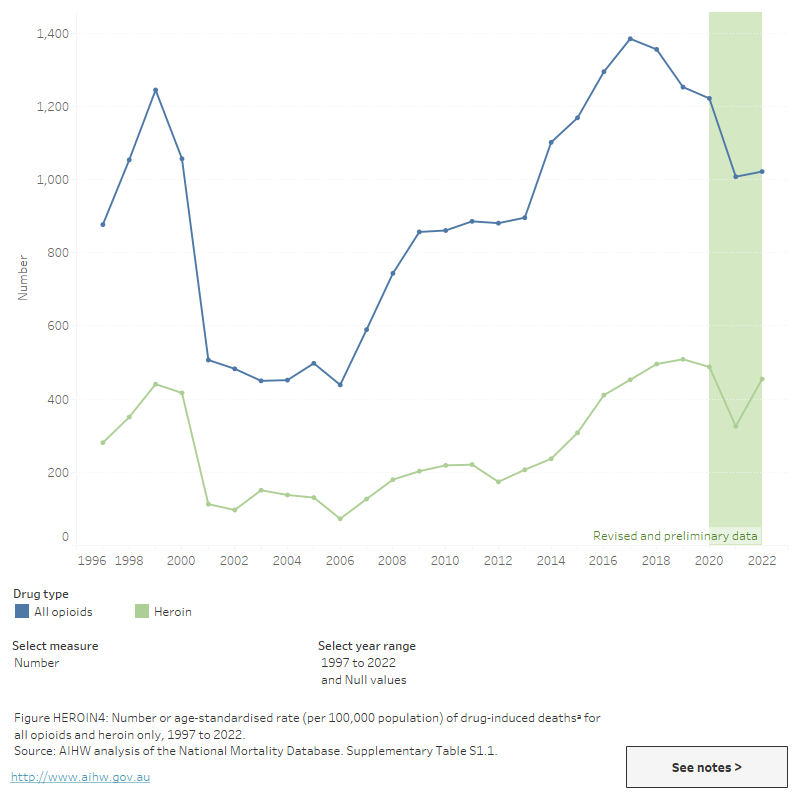

Deaths

Drug-induced deaths are determined by toxicology and pathology reports and are defined as those deaths that can be directly attributable to drug use. This includes deaths due to acute toxicity (for example, drug overdose) and chronic use (for example, drug-induced cardiac conditions) (ABS 2021).

People who use heroin have a particularly high risk of overdose, especially when heroin is used in conjunction with other drugs like benzodiazepines (for example, alprazolam, diazepam) and alcohol. However, there are some challenges in interpreting the numbers of heroin deaths. Heroin can be difficult to identify at toxicology because it is rapidly metabolised to morphine by the body and these metabolites cannot be distinguished from other morphine sources (for example, codeine).

Opioids, including both licit and illicit substances, have been the leading class of drug present in drug-induced deaths in Australia for the last 2 decades. While illicit opioids include opium as well as heroin, most illicit opioid deaths involve heroin – opium or unspecified opioids accounted for very few opioid-induced deaths (less than 10) in 2021 (Chrzanowska et al. 2023).

Of the 1,693 drug-induced deaths in Australia in 2022, 455 or 27%, were due to heroin–an increase from 326 deaths (or 18% of all drug-induced deaths) in 2021 (Table S1.1). The rate of deaths involving heroin has overall declined since the late 1990s, when heroin consumption was at its peak in Australia (Degenhardt, Day & Hall 2004). However, deaths involving heroin have shown an increase over the last decade, from 0.9 per 100,000 people in 2013 to 2.1 in 2018 and 2019. It has since decreased to 1.8 in 2022 (Figure HEROIN3; Table S1.1).

In 2018, deaths with heroin identified had a median age at death of 42.1 years, lower than for pharmaceutical opioids (median 46.6 years) (ABS 2019).

Figure HEROIN4: Number or age-standardised rate (per 100,000 population) of drug-induced deathsa for all opioids and heroin only, 1997 to 2022

The figure shows the number of drug-induced deaths due to all opioids and heroin only steadily increased from 2006 to 2017. The number of deaths due to all opioids has decreased from 1,385 in 2017 to 962 in 2021. The number of deaths due to heroin has decreased from 453 to 315 in the same period.

Treatment

The latest Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia: early insights report shows that heroin was the principal drug of concern in 4.5% of treatment episodes provided to people for their own drug use (AIHW 2024a). This is the same as 2020–21.

Data collected for the AODTS NMDS are released twice each year: an early insights report in April and a detailed report mid-year. The section below will be updated with information from the annual report once these data become available.

The Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services National Minimum Data Set (AODTS NMDS) provides information on treatment provided to clients by publicly funded AOD treatment services, including government and non-government organisations.

Data from the AODTS NMDS showed that heroin was the fourth most common principal drug of concern in closed treatment episodes provided to clients in 2021–22 (Figure HEROIN4).

In 2021–22, where heroin was the principal drug of concern:

- Most (68%) clients were male and 1 in 5 (21%) were Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2023a, tables SC.9 and SC.11).

- Over two-thirds of clients were aged 30–39 (35% of clients) or 40–49 (33%) (AIHW 2023a, Table SC.10).

- The most common source of referral was self or family (43% of treatment episodes), followed by a health service (28%) (AIHW 2023a, Table Drg.55).

- Counselling and assessment only were the most common main treatment types (both 21% of treatment episodes), followed by pharmacotherapy (19%) (AIHW 2023a, Table Drg.54).

Figure HEROIN5: Treatment provided for own use of heroin, 2021–22

Heroin was the 4th most common principal drug of concern (4.5% of treatment episodes)

Nearly 1 in 5 clients were Indigenous Australians

Counselling was the most common main treatment type(over 1 in 5 episodes)

Source: AIHW 2023, tables Drg.1, SC.11 and Drg.54.

Treatment agencies whose sole function is prescribing or providing dosing services for opioid pharmacotherapy are excluded from the AODTS NMDS. Due to the multi-faceted nature of service delivery in this sector, these data are captured in the National Opioid Pharmacotherapy Statistics Annual Data (NOPSAD) collection.

NOPSAD data showed that, on a snapshot day in 2022, 36% of clients across Australia reported heroin as their opioid drug of dependence. However, these data should be used with caution due to the high proportion of clients with ‘Not stated/not reported’ as their drug of dependence; this was the case for 38% of clients overall (AIHW 2023b).

Further information on pharmacotherapy in Australia >

At-risk groups

For related content on at-risk groups, see:

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2019). Opioid-induced deaths in Australia. Canberra: ABS, accessed 26 October 2021.

ABS (2021). Causes of Death, Australia, 2021. ABS cat. no. 3303.0. Canberra: ABS, accessed 29 September 2021.

ACIC (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission) (2019). Illicit Drug Data Report 2017–18. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 7 August 2019.

ACIC (2023) Illicit Drug Data Report 2020–2021. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 24 October 2023.

ACIC (2024) National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program Report 21. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 14 March 2024.

AIHW (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018, AIHW, Australian Government. doi:10.25816/5ps1-j259

AIHW (2022). Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018. Cat. no. PHE 266. Canberra: AIHW, accessed 7 March 2022.

AIHW (2023a).Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services annual report. Cat. No. HSE 250. Canberra: AIHW, accessed 21 June 2023.

AIHW (2023b). National Opioid Pharmacotherapy Statistics Annual Data collection, Canberra: AIHW, accessed 20 April 2023

AIHW (2024a) Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia: early insights. AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 16 April 2024.

AIHW (2024b) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023. AIHW, accessed 22 February 2024.

Chrzanowska A, Man N, Akhurst J, Sutherland R, Degenhardt, L Peacock A (2023). Trends in overdose and other drug-induced deaths in Australia, 2002-2021. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney, accessed 4 May 2023.

Degenhardt L, Day C & Hall W (2004). The causes, course and consequences of the heroin shortage in Australia. Canberra: National Drug Law Enforcement Research Fund.

Degenhardt L, Reuter P, Collins L & Hall W (2004). ‘Chapter 5: Evaluating factors responsible for the heroin shortage’ in The causes, courses and consequences of the heroin shortage in Australia. Degenhardt L, Day C & Hall W (eds). Monograph no. 3. Canberra: National Drug and Law Enforcement Research Fund, accessed 14 December 2017.

Nielsen S & Gisev N (2017). Drug pharmacology and pharmacotherapy treatments. In: Ritter, King and Lee (eds). Drug use in Australian society. 2nd edn. Oxford University Press.

NSW Ministry of Health (2017). A quick guide to drugs and alcohol, 3rd edn. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.

Peacock A, Uporova J, Karlsson A, Gibbs D, Swanton R, Kelly G, Price O, Bruno R, Dietze P, Lenton S, Salom C, Degenhardt L & Farrell M (2019). Australian Drug Trends 2019: Key findings from the National Illicit Drug Reporting System Interviews. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Australia.

Sutherland R, Uporova J, King C, Chandrasena U, Karlsson A, Jones F, Gibbs D, Price O, Dietze P, Lenton S, Salom C, Bruno R, Wilson J, Agramunt S, Daly C, Thomas N, Radke S, Stafford L, Degenhardt L, Farrell M, & Peacock A (2023). Australian Drug Trends 2023: Key Findings from the National Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) Interviews. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney. Accessed 25 October 2023.