FDSV and COVID-19

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

This topic page examines the effects the COVID-19 pandemic had on FDSV in Australia using information available prior to 15 November 2023. Other topic pages in this website are regularly updated with data from a range of sources and may provide more recently available data. For more information, see the Release schedule.

Key findings

- Between 2016 and 2021–22 the proportion of women who experienced physical and/or sexual violence by a cohabiting partner decreased from 1.7% to 0.9%.

- The proportion of women and men who experienced emotional abuse by a cohabiting partner decreased between 2016 (women: 4.8%, men: 4.2%) and 2021–22 (women: 3.9%, men: 2.5%).

- Available data on FDSV service use during the pandemic show that the picture is mixed. Service use can change for several reasons, including due to public awareness campaigns or changes to availability or accessibility of services.

With ready access to vaccines and treatments, as well as high population immunity, Australia is no longer in the emergency phase of the COVID-19 pandemic response (DoHAC 2023). While the country has moved towards managing COVID-19 in a manner that is more consistent with other infectious diseases, we are still learning about the impact of the pandemic and related public heath responses on family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV).

The effects of a pandemic can be wide-ranging with people experiencing different impacts depending on their situation. Situational stressors experienced during the pandemic may have influenced the severity or frequency of violence. For example, victims and perpetrators spending more or less time together, and increased financial or economic hardship (Payne et al. 2020). It is also possible that increased protective factors, such as access to income support, time away from a perpetrator, or increased social cohesion, could suppress violence (Diemer 2023). Pandemics may also impact how individuals respond to incidents of violence through the actions they take.

We continue to learn about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on FDSV. By improving our understanding of the short- and long-term impacts of the pandemic, we can better prepare for future pandemics and disaster events.

COVID-19 in Australia

In terms of morbidity and mortality, COVID-19 has had less of an impact on Australia than many other countries (OECD 2021). However, Australia has not been spared, with multiple waves of the disease having varying impacts across the states and territories (Box 1).

COVID-19 was first declared a human biosecurity emergency in March 2020, with the determination expiring in April 2022 (DoHAC 2022). During this time, the number of COVID-19 cases varied across age groups, with older people at greater risk of having poorer outcomes from COVID-19. Mortality rates were highest in people aged 80 years and over, with 30% of all COVID-19 deaths in Australia occurring in residents of aged care facilities (AIHW 2022).

While new variants, sub-variants and lineages are likely to continue to emerge, under the current approach to managing COVID-19 it is less likely that we will experience the public health restrictions associated with previous waves.

This page focuses primarily on FDSV during the emergency phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the prevalence of FDSV, service responses to FDSV and differences in experiences of FDSV across select population groups. More general information about the impact of COVID-19 on the Australian population can be found on the AIHW’s COVID-19 page.

In Australia, the prevalence of COVID-19 has varied across the states and territories over time. The waves of COVID-19 are summarised below, including the main locations affected.

- The first wave occurred from March to April 2020 at the start of the pandemic, with cases in all states and territories.

- The second wave began in the winter of 2020, with most cases in Victoria.

- The third wave started in the winter of 2021 and daily case numbers started to decline from the end of October 2021. While most cases in the third wave were in New South Wales and Victoria, there was also a major outbreak in the Australian Capital Territory.

- The fourth wave started in December 2021 after the introduction of Omicron BA.1. It affected all jurisdictions. International and domestic border restrictions – and a suite of public health restrictions that continued into 2022 – resulted in a delayed but rapid progression of COVID-19 cases during March 2022 in Western Australia. The Omicron wave for Australia flattened from the end of January 2022 but increased again at the end of March 2022 when BA.2 became the dominant sub-variant.

Each wave was associated with a range of public health restrictions, which also differed across states and territories.

What do we know?

From the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, a range of public health measures were implemented to limit the spread of COVID-19. These measures included stay-at-home orders, border closures, and restrictions on the way businesses, schools, residential aged care and public services operated. These had an effect on the community and economy, and resulted in significant changes to people’s mobility, social interactions and home environments.

Within many households, individuals, couples and families had to deal with the additional pressures of job losses, increased financial stress, home-learning and added caring responsibilities (ABS 2021a; Hand et al. 2020). For some, the pandemic also had implications for alcohol use and mental health:

- 1 in 5 (20%) adults who usually drank alcohol said their alcohol consumption increased during COVID-19 restrictions, however between 13% and 27% said it had decreased (AIHW 2021a).

- The prevalence of ‘severe’ psychological distress in adults rose from 8.4% in February 2017 to 10.6% in April 2020, reaching a peak of 12.5% in October 2021– the highest level recorded since the onset of the pandemic (AIHW 2021b).

These factors, combined with increased social isolation and reduced access to sources of support, are not causes of FDSV themselves, but can be seen as situational stressors that can exacerbate the underlying drivers of violence and increase the likelihood, complexity and severity of violence (Boxall and Morgan 2021a; Peterman et al. 2020).

However, people experienced the pandemic in different ways. For some, the pandemic brought about a range of situations that may have decreased the likelihood of violence (Diemer 2023). For example, imposed social restrictions may have limited contact between victims and perpetrators if they were “locked down” in separate houses. The restrictions may have also resulted in fewer opportunities for victims to be approached by their perpetrators in the community, as attendance at venues and activities (for example, workplaces, children’s sports events) was limited (Hegarty et al. 2022).

Similarly, while many households and businesses were strongly financially affected by the health restrictions (The Treasury 2021), some people reported that pandemic-related income support payments helped to reduce levels of financial stress (Botha, Butterworth and Wilkins 2022).

In a 2022 report, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) presented results from a survey of over 1,000 women victim-survivors about their experiences of intimate partner violence. Qualitative questions explored how intimate relationships were affected during periods of COVID-19-related isolation (Hegarty et al. 2022). The responses below offer insight into some women’s experiences during the pandemic:

'It was easier for my ex-partner to manipulate me when I was cut off from the outside world.'

'[It’s] definitely worse during lockdowns – he can still access alcohol/cigarettes and all the things that fuel his behaviour – I was not able to access any support to assist with being away from the abuse such as gyms, yoga class etc.'

'I felt safer as I didn’t need to go into my work premises where he (or his family/friends) could be … [and] I feel safer at home as I know I’m unlikely to be being watched.' (Hegarty et al. 2022: 54-55).

A range of data sources can be used to understand the nature and extent of FDSV during the pandemic, and the demand for FDSV services. It is important to note that results from different sources, using different methods, are not comparable and need to be interpreted within the specific context they were collected.

- ABS Personal Safety Survey

- ABS Recorded Crime – Offenders

- ABS Recorded Crime – Victims

- AIHW Child Protection National Minimum Data Set

- AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

- AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Collection

- Kids Helpline

- Services Australia customer data – Crisis payments

For more information about these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

What do the data tell us?

The following sections present a range of data collected during the pandemic. Data are primarily drawn from standard data collections, however the results of COVID-specific surveys are also included. Depending on data availability, analysis of FDSV data may focus on:

- national population prevalence data collected during the pandemic (March 2021 to May 2022), compared with previous survey year

- changes that occurred at the onset of the pandemic (March–May 2020) compared with previous years for the same month, to account for seasonal effects

- changes that occurred over the duration of the pandemic to date, to identify variations that may be associated with the waves of COVID-19 in Australia (Box 1)

- yearly data to provide context for overall changes in patterns of FDSV or service use over time.

Due to the differences in how states and territories have experienced the pandemic, data are presented by state and territory where appropriate. This information updates and expands on the AIHW’s Family, domestic and sexual violence service responses in the time of COVID-19 report.

How common was FDSV during the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

The proportion of women who experienced physical and/or sexual violence by a cohabiting partner decreased from 1.7% to 0.9% between 2016 and 2021–22

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey

It is difficult to capture the full extent of FDSV, as incidents often occur behind closed doors, and can be concealed or denied by perpetrators and sometimes by the victims. In Australia, the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) Personal Safety Survey (PSS) is the source of national FDSV prevalence data for adults aged 18 years and over.

The most recent PSS was conducted between March 2021 and May 2022, during the COVID-19 pandemic (ABS 2023a). Key FDSV-related survey findings are presented in Table 1, showing the prevalence of select types of FDSV in the 12 months before the survey, compared with 2016 results.

Between 2016 and 2021–22 there was:

- a decrease in the proportion of women who experienced physical and/or sexual violence by a cohabiting partner

- a decrease in the proportion of women and men who experienced emotional abuse by a cohabiting partner

- no change in the proportion of women who experienced sexual violence

- a decrease in the proportion of men and women who experienced sexual harassment (ABS 2023a).

Note that due to data quality issues, data for men are not available in some instances.

| Prevalence rate(a) | Prevalence rate(a) males | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Type of violence | 2016 | 2021–22 | 2016 | 2021–22 |

Sexual violence | 1.8% | 1.9% | *0.7% | n.p. |

Intimate partner violence(b) | 2.3% | 1.5%^ | 1.3% | n.p. |

Cohabiting partner violence(c) (Total) | 1.7% | 0.9%^ | 0.8% | n.p. |

Cohabiting partner violence(c) – Physical violence | 1.3% | 0.7%^ | 0.8% | n.p. |

Cohabiting partner violence(c) –Sexual violence | 0.5% | 0.4% | n.p. | – |

Cohabiting partner emotional abuse | 4.8% | 3.9%^ | 4.2% | 2.5%^ |

Sexual harassment | 17.3% | 12.6%^ | 9.3% | 4.5%^ |

Stalking | 3.1% | 3.4% | 1.7% | n.p. |

*: Estimate should be used with caution because Relative Standard Error (RSE) is between 25% and 50%.

^: The difference in prevalence rate between 2021–22 and 2016 is statistically significant.

–: Nil or rounded to zero. Does not necessarily indicate a complete absence of the characteristic in the population.

n.p.: not published due to reliability and/or confidentiality reasons.

- The proportion (rate) of people in each population that have experienced the selected type of violence in the last 12 months.

- Physical or sexual violence by a cohabiting partner, boyfriend/girlfriend or date, and ex-boyfriend/ex-girlfriend.

- Violence experienced by a partner the person lives with, or has lived with at some point, in a married or de facto relationship.

Source: ABS (2023a).

Using a different methodology to the PSS, findings from an online survey conducted by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) indicated that the pandemic coincided with first-time and escalating intimate partner violence in Australia for some women (Table 2). The survey was completed by more than 10,100 women between 16 February 2021 and 6 April 2021 and asked about experiences of intimate partner violence in the 12 months before the survey.

| Physical violence | Sexual violence | Emotionally abusive, harassing and controlling behaviours | |

|---|---|---|---|

Overall prevalence of intimate partner violence (b) | 9.6% | 7.6% | 32% |

Experienced intimate partner violence for the first time (b) | 3.4% | 3.2% | 18% |

Reported that intimate partner violence had increased in frequency or severity (b, c) | 42% | 43% | 40% |

- Violence from a person the respondent had a relationship with during the previous 12 months. This includes current and former partners, cohabiting, or non-cohabiting.

- Of women aged 18 years and older who had been in a relationship longer than 12 months.

- Of women who had a history of violence from their current or most recent partner.

Source: Boxall and Morgan 2021a.

What were the service responses to FDSV during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Between 2020 and 2022, there were numerous reports of increased demand for services related to FDSV (for example, Pfitzner et al. 2020; Carrington et al 2021). These reports drew from data sources that include police, domestic violence helplines, specialist crisis services and workforce surveys. FDSV services span a number of sectors and the introduction of COVID-19 restrictions had differing impacts on the availability and accessibility of these services (Box 2).

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the way FDSV services are delivered. For example, the move towards remote working in some services may have led to face-to-face contact being replaced by telephone, videoconferencing or other online contact. Changes in how FDSV services were provided increased the complexity of delivering some forms of service or support, particularly for select population groups (Carrington et al. 2021). However, for some people it improved the accessibility of services.

When considering changes in FDSV-related service use, it is important to be aware that changes in service use may be due to a combination of factors. For example, an increase in service use may be a result of increased availability of services, increased awareness of services and FDSV in general, and/or increased need for services (AIHW 2019).

Note that data on service use capture only part of the picture. A large proportion of FDSV goes undisclosed and may never enter into view of services. COVID-19 restrictions can make it more difficult for victims and survivors to seek assistance or leave abusive relationships and this may not be reflected in the data.

Helplines

Helplines are an important point of contact for those experiencing family and domestic violence. For more information, see Helplines and related support services.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, helplines were especially important as they provide options to seek help without leaving the home.

Kids Helpline counselling contacts increased at the onset of the pandemic

Kids Helpline provides support and counselling for children and young people aged 5 to 25. Children and young people contact Kids Helpline about diverse issues, including child abuse, family and relationship issues, and forms of sexual harassment and abuse.

As shown in Figure 1, data on counselling contacts indicates that after the onset of COVID-19, there was:

- an increase in the number of family relationship concerns being discussed (44% change from Q2 2019 to Q2 2020), and another peak around the beginning of wave 2. From 2022, the number of family relationship concerns being discussed during counselling contacts appeared to be trending back towards pre-pandemic numbers.

- an increase in the number of child abuse and family violence concerns being discussed (41% change from Q2 2019 to Q2 2020). The number of concerns discussed during counselling contacts peaked at 1,985 contacts in the second quarter of 2021 (around the beginning of wave 2) with numbers getting closer to pre-pandemic levels in 2022.

- the number of sexual violence and harassment (including child sexual abuse) concerns being discussed increased slightly in 2020 compared to 2019. The number of concerns being discussed during counselling contacts peaked in the fourth quarter of 2021 at 626 calls.

- the number of concerns related to dating and partner abuse being discussed during counselling contacts remained relatively steady throughout the pandemic.

Figure 1: Number of FDSV-related concerns discussed during Kids Helpline counselling contacts, January 2018 to December 2022

| Quarter | Child abuse and family violence | Dating and partner abuse | Family relationship issues | Sexual offending | Sexual violence and harassment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-Q1 | 1,124 | 87 | 2,636 | 4 | 243 |

| 2018-Q2 | 1,133 | 85 | 2,557 | 13 | 286 |

| 2018-Q3 | 1,152 | 102 | 2,617 | 11 | 303 |

| 2018-Q4 | 1,313 | 81 | 2,915 | 15 | 367 |

| 2019-Q1 | 1,300 | 88 | 2,924 | 12 | 329 |

| 2019-Q2 | 1,201 | 113 | 2,958 | 20 | 367 |

| 2019-Q3 | 1,221 | 123 | 2,752 | 1 | 325 |

| 2019-Q4 | 1,283 | 104 | 3,140 | 8 | 359 |

| 2020-Q1 | 1,288 | 136 | 3,106 | 14 | 343 |

| 2020-Q2 | 1,699 | 136 | 4,270 | 21 | 363 |

| 2020-Q3 | 1,804 | 116 | 4,219 | 20 | 426 |

| 2020-Q4 | 1,782 | 130 | 4,030 | 15 | 377 |

| 2021-Q1 | 1,811 | 124 | 3,991 | 18 | 427 |

| 2021-Q2 | 1,985 | 111 | 4,105 | 28 | 478 |

| 2021-Q3 | 1,874 | 114 | 3,900 | 18 | 540 |

| 2021-Q4 | 1,838 | 92 | 3,725 | 29 | 626 |

| 2022-Q1 | 1,581 | 71 | 3,390 | 14 | 452 |

| 2022-Q2 | 1,486 | 77 | 2,905 | 21 | 549 |

| 2022-Q3 | 1,400 | 100 | 2,877 | 7 | 590 |

| 2022-Q4 | 1,328 | 80 | 3,031 | 16 | 530 |

Note:

- Numbers reflect the number of times a concern type was raised during all counselling contacts. They do not reflect a count of unique individuals, counselling contacts or incidents. Each contact can include counselling for more than one concern type and/or the same concern type multiple times for different incidents discussed. Clients may also contact Kids Helpline more than once about the same incident. Concern type is counted separately in each of these instances.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

Kids Helpline (unpublished data)

|

Data source overview

Figure 2 shows the number of Kids Helpline counselling contacts where child abuse and family violence were discussed, by states and territories. Contacts related to child sexual abuse are included in these counts. The time series shows that patterns in the number of contacts varied across states and territories.

Figure 2: Number of child abuse and family violence concerns discussed during Kids Helpline counselling contacts, states and territories, 2018 to 2022

| Quarter | New South Wales | Victoria | Queensland | Western Australia | South Australia | Tasmania | Australian Capital Territory | Northern Territory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-Q1 | 297 | 234 | 237 | 68 | 63 | 48 | 13 | 3 |

| 2018-Q2 | 285 | 216 | 210 | 75 | 71 | 36 | 18 | 7 |

| 2018-Q3 | 293 | 251 | 239 | 71 | 78 | 35 | 13 | 6 |

| 2018-Q4 | 331 | 266 | 269 | 95 | 105 | 52 | 13 | 8 |

| 2019-Q1 | 312 | 303 | 281 | 83 | 79 | 34 | 27 | 9 |

| 2019-Q2 | 284 | 254 | 283 | 73 | 82 | 27 | 26 | 3 |

| 2019-Q3 | 310 | 297 | 233 | 91 | 64 | 29 | 19 | 5 |

| 2019-Q4 | 319 | 287 | 260 | 87 | 79 | 34 | 17 | 6 |

| 2020-Q1 | 344 | 267 | 258 | 90 | 97 | 25 | 19 | 7 |

| 2020-Q2 | 400 | 368 | 314 | 122 | 102 | 31 | 32 | 10 |

| 2020-Q3 | 461 | 453 | 311 | 108 | 120 | 23 | 25 | 13 |

| 2020-Q4 | 428 | 484 | 349 | 136 | 99 | 32 | 31 | 9 |

| 2021-Q1 | 453 | 465 | 338 | 113 | 155 | 26 | 31 | 2 |

| 2021-Q2 | 485 | 460 | 395 | 142 | 123 | 40 | 30 | 11 |

| 2021-Q3 | 566 | 394 | 301 | 123 | 121 | 38 | 35 | 4 |

| 2021-Q4 | 472 | 353 | 342 | 121 | 125 | 44 | 52 | 13 |

| 2022-Q1 | 438 | 244 | 293 | 115 | 127 | 30 | 44 | 9 |

| 2022-Q2 | 367 | 252 | 281 | 93 | 104 | 24 | 25 | 9 |

| 2022-Q3 | 347 | 283 | 242 | 92 | 98 | 32 | 25 | 5 |

| 2022-Q4 | 353 | 259 | 262 | 81 | 104 | 18 | 20 | 2 |

Note:

- Numbers reflect the number of times a concern type was raised during all counselling contacts. They do not reflect a count of unique individuals, counselling contacts or incidents. Each contact can include counselling for more than one concern type and/or the same concern type multiple times for different incidents discussed. Clients may also contact Kids Helpline more than once about the same incident. Concern type is counted separately in each of these instances.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

Kids Helpline (unpublished data)

|

Data source overview

Kids Helpline also provides emergency responses for children and young people. Emergency responses involve contacting emergency services or another agency to protect a young person who is experiencing, or is at imminent risk of, significant harm. In 2021, average daily emergency responses increased in states and territories experiencing lockdowns. For example, in NSW there were 2 additional emergency responses, on average, each day during lockdown (YourTown 2021).

Child protection

The child protection system aims to protect children from maltreatment in family settings. For more information, see Child protection.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have affected child protection processes, and changes to people’s mobility and interactions may also have affected the way child maltreatment was detected or reported (AIHW 2021c).

At the same time, the pandemic affected the way families live and work. Several risk factors for child maltreatment increased during COVID-19, including financial hardship, housing stress, and poor mental health. Access to support networks may also have been limited during this time.

Data from the child protection system are available between March and August 2020 to show changes at the onset of the pandemic, including the first and part of the second wave of COVID-19 in Australia. Key findings include:

- Child protection notifications fluctuated considerably between March and August 2020, and patterns varied across jurisdictions. A common pattern observed in most jurisdictions was a drop in notifications in April 2020 (during the initial COVID-19 restrictions) followed by an increase in May or June (once restrictions had eased).

- The number of substantiations recorded each month remained relatively stable from March to August 2020 for all jurisdictions (data were not available for Tasmania). However, the total number of substantiations for the 6-month period varied across jurisdictions (AIHW 2021c).

The AIHW’s Child protection in the time of COVID-19 report provides more detail on the impact of the early stages of COVID-19 observed in child protection data. While the long-term impact of COVID-19 on child protection processes is still unknown, there have been no specific impacts on the annual data.

Specialist homelessness services

Family and domestic violence is the most common main reason clients seek assistance from specialist homelessness services (SHS). For more information, see Housing.

A nationwide survey of service providers highlighted that public health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic often made it harder for victim-survivors to leave a violent relationship, due to travel restrictions, lack of transport options, and difficulty accessing formal and informal support. Financial stress also meant that victim-survivors may no longer be able to afford rent, leading to increased housing instability (Morley et al. 2021). In recognition of the increased pressure on homelessness services during the pandemic, some governments invested additional funding to increase the operational capacity of these services (for example, Williams 2020).

The number of SHS clients who have experienced FDV peaked around the third wave of COVID-19

The number of SHS clients who have experienced family and domestic violence was similar in April 2020 compared with previous years (Figure 3) (AIHW 2021d). Over the 5 years to December 2022, the monthly number of FDV clients receiving assistance from SHS peaked around the winter of 2021, around the time of the third wave of COVID-19. However, the number of SHS clients who received support changes from one month to the next for many reasons and are not necessarily due to changes in demand.

Figure 3: Number of FDV clients receiving assistance from SHS, July 2017 to December 2022

| Month | NSW | Vic | Qld | WA | SA | Tas | ACT | NT | National |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 17 | 7,068 | 12,656 | 2,949 | 2,518 | 1,921 | 559 | 517 | 978 | 29,108 |

| Aug 17 | 7,207 | 13,151 | 3,106 | 2,606 | 1,952 | 588 | 514 | 1,025 | 30,085 |

| Sep 17 | 7,304 | 12,820 | 3,038 | 2,411 | 1,992 | 535 | 493 | 976 | 29,490 |

| Oct 17 | 7,399 | 13,184 | 3,071 | 2,648 | 2,070 | 523 | 521 | 1,073 | 30,428 |

| Nov 17 | 7,588 | 13,226 | 3,162 | 2,603 | 2,036 | 547 | 527 | 1,080 | 30,702 |

| Dec 17 | 7,070 | 12,941 | 2,943 | 2,614 | 1,874 | 484 | 489 | 986 | 29,350 |

| Jan 18 | 7,523 | 13,524 | 3,247 | 2,691 | 1,978 | 508 | 555 | 1,030 | 31,006 |

| Feb 18 | 7,735 | 13,462 | 3,181 | 2,676 | 1,946 | 501 | 557 | 998 | 30,999 |

| Mar 18 | 7,762 | 13,928 | 3,212 | 2,628 | 1,950 | 470 | 557 | 963 | 31,394 |

| Apr 18 | 7,775 | 13,786 | 3,245 | 2,494 | 1,871 | 469 | 538 | 1,027 | 31,155 |

| May 18 | 8,060 | 14,700 | 3,309 | 2,526 | 1,994 | 443 | 547 | 993 | 32,525 |

| Jun 18 | 7,841 | 13,830 | 3,116 | 2,579 | 1,880 | 408 | 541 | 1,070 | 31,208 |

| Jul 18 | 8,005 | 13,864 | 3,062 | 2,676 | 1,944 | 396 | 526 | 1,007 | 31,431 |

| Aug 18 | 8,239 | 13,012 | 3,128 | 2,783 | 1,926 | 423 | 538 | 1,091 | 31,084 |

| Sep 18 | 7,900 | 12,418 | 3,016 | 2,614 | 1,956 | 478 | 515 | 1,014 | 29,851 |

| Oct 18 | 8,117 | 13,095 | 3,358 | 2,856 | 2,092 | 523 | 498 | 1,095 | 31,567 |

| Nov 18 | 8,113 | 13,617 | 3,437 | 2,740 | 1,986 | 504 | 524 | 1,168 | 32,014 |

| Dec 18 | 7,542 | 13,292 | 3,325 | 2,851 | 1,708 | 449 | 498 | 1,109 | 30,722 |

| Jan 19 | 7,913 | 13,818 | 3,630 | 2,988 | 1,851 | 489 | 521 | 1,119 | 32,275 |

| Feb 19 | 7,966 | 13,986 | 3,549 | 2,915 | 1,883 | 526 | 529 | 976 | 32,254 |

| Mar 19 | 7,928 | 14,091 | 3,581 | 2,974 | 2,013 | 537 | 540 | 1,094 | 32,682 |

| Apr 19 | 7,791 | 13,861 | 3,361 | 2,841 | 1,847 | 533 | 527 | 1,017 | 31,731 |

| May 19 | 8,042 | 14,393 | 3,443 | 2,893 | 1,971 | 517 | 522 | 1,035 | 32,758 |

| Jun 19 | 7,714 | 13,719 | 3,316 | 2,755 | 1,804 | 499 | 503 | 932 | 31,177 |

| Jul 19 | 7,832 | 14,452 | 3,427 | 2,757 | 1,846 | 531 | 541 | 992 | 32,317 |

| Aug 19 | 7,786 | 14,315 | 3,342 | 2,906 | 1,789 | 530 | 568 | 993 | 32,173 |

| Sep 19 | 7,676 | 13,967 | 3,403 | 2,690 | 1,785 | 509 | 542 | 998 | 31,527 |

| Oct 19 | 7,832 | 14,670 | 3,521 | 2,729 | 1,818 | 501 | 597 | 1,099 | 32,721 |

| Nov 19 | 7,743 | 14,593 | 3,593 | 2,831 | 1,790 | 499 | 624 | 1,051 | 32,660 |

| Dec 19 | 7,320 | 14,588 | 3,509 | 2,772 | 1,741 | 501 | 620 | 1,002 | 31,996 |

| Jan 20 | 7,891 | 14,619 | 3,940 | 2,742 | 1,732 | 536 | 640 | 968 | 33,003 |

| Feb 20 | 7,996 | 14,462 | 4,017 | 2,610 | 1,794 | 502 | 637 | 987 | 32,953 |

| Mar 20 | 8,055 | 14,674 | 3,786 | 2,598 | 1,763 | 503 | 699 | 1,018 | 33,035 |

| Apr 20 | 7,812 | 14,079 | 3,497 | 2,454 | 1,747 | 505 | 744 | 935 | 31,732 |

| May 20 | 7,897 | 14,216 | 3,536 | 2,567 | 1,776 | 500 | 746 | 909 | 32,093 |

| Jun 20 | 8,105 | 14,563 | 3,582 | 2,550 | 1,801 | 528 | 761 | 1,036 | 32,875 |

| Jul 20 | 7,936 | 14,393 | 3,668 | 2,553 | 1,810 | 530 | 744 | 1,015 | 32,571 |

| Aug 20 | 8,004 | 14,245 | 3,669 | 2,608 | 1,780 | 553 | 746 | 1,056 | 32,614 |

| Sep 20 | 8,284 | 14,607 | 3,800 | 2,736 | 1,812 | 525 | 743 | 1,212 | 33,673 |

| Oct 20 | 8,363 | 14,437 | 3,819 | 2,849 | 1,781 | 533 | 726 | 1,207 | 33,644 |

| Nov 20 | 8,410 | 14,557 | 3,737 | 2,788 | 1,749 | 542 | 703 | 1,393 | 33,821 |

| Dec 20 | 8,141 | 14,330 | 3,681 | 2,907 | 1,696 | 530 | 684 | 1,338 | 33,240 |

| Jan 21 | 8,362 | 13,928 | 3,740 | 3,040 | 1,574 | 557 | 727 | 1,321 | 33,184 |

| Feb 21 | 8,639 | 14,181 | 3,841 | 3,041 | 1,684 | 568 | 744 | 1,263 | 33,885 |

| Mar 21 | 8,937 | 14,524 | 4,005 | 3,263 | 1,855 | 598 | 726 | 1,253 | 35,089 |

| Apr 21 | 8,760 | 14,169 | 3,695 | 3,141 | 1,716 | 538 | 722 | 1,230 | 33,897 |

| May 21 | 8,910 | 14,817 | 3,944 | 3,177 | 1,756 | 558 | 726 | 1,177 | 35,008 |

| Jun 21 | 8,676 | 14,931 | 4,019 | 3,064 | 1,727 | 564 | 714 | 1,220 | 34,868 |

| Jul 21 | 8,483 | 14,836 | 3,923 | 3,001 | 1,154 | 578 | 712 | 1,224 | 33,858 |

| Aug 21 | 8,424 | 14,684 | 3,898 | 3,024 | 1,519 | 597 | 714 | 1,180 | 33,997 |

| Sep 21 | 8,275 | 14,386 | 3,750 | 3,065 | 1,560 | 554 | 729 | 1,335 | 33,607 |

| Oct 21 | 8,258 | 14,357 | 3,830 | 3,106 | 1,528 | 541 | 760 | 1,289 | 33,615 |

| Nov 21 | 8,614 | 14,292 | 4,016 | 3,098 | 1,545 | 520 | 761 | 1,254 | 34,045 |

| Dec 21 | 8,219 | 13,740 | 3,666 | 3,048 | 1,396 | 499 | 732 | 1,203 | 32,437 |

| Jan 22 | 8,165 | 13,472 | 3,671 | 3,047 | 1,432 | 500 | 720 | 1,035 | 31,981 |

| Feb 22 | 8,271 | 13,918 | 3,678 | 2,936 | 1,518 | 527 | 720 | 909 | 32,416 |

| Mar 22 | 8,492 | 14,038 | 3,803 | 2,969 | 1,583 | 570 | 708 | 1,137 | 33,233 |

| Apr 22 | 7,960 | 13,289 | 3,595 | 2,850 | 1,425 | 554 | 696 | 1,106 | 31,404 |

| May 22 | 8,073 | 13,763 | 3,745 | 3,012 | 1,532 | 545 | 686 | 1,118 | 32,396 |

| Jun 22 | 7,924 | 13,472 | 3,824 | 2,912 | 1,438 | 544 | 700 | 1,154 | 31,899 |

| Jul 22 | 7,764 | 13,234 | 3,697 | 2,945 | 1,382 | 546 | 700 | 1,035 | 31,243 |

| Aug 22 | 8,006 | 13,558 | 3,750 | 3,116 | 1,413 | 568 | 710 | 1,059 | 32,110 |

| Sep 22 | 7,960 | 13,315 | 3,872 | 2,964 | 1,547 | 548 | 723 | 1,100 | 31,991 |

| Oct 22 | 7,907 | 12,999 | 3,963 | 3,017 | 1,552 | 564 | 748 | 1,084 | 31,784 |

| Nov 22 | 7,996 | 12,917 | 4,111 | 3,076 | 1,519 | 605 | 781 | 1,177 | 32,131 |

| Dec 22 | 7,561 | 12,448 | 4,030 | 3,146 | 1,521 | 557 | 754 | 1,143 | 31,122 |

Note:

- Components cannot be added together to form a total. Reported Totals include non-response and data otherwise not publishable.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

AIHW SHSC

|

Data source overview

Government payments

People who are in severe financial hardship and have experienced changes in their living arrangements due to family and/or domestic violence, and are receiving, or are eligible to receive, an income support payment or ABSTUDY Living Allowance, may receive a one-off Crisis Payment. For more information, see Financial support and workplace responses.

Number of FDV Crisis Payments granted fell at the onset of the pandemic

Overall, the number of claims for FDV Crisis Payments granted annually rose between 2018 and 2021, with a small decrease in 2022. The highest number of claims granted per month was in March 2021 at just over 2,400 claims.

The number of FDV Crisis Payment claims granted was lower in April and May 2020 compared with the same period in previous years (see Figure 4). There were 1,337 claims granted in April 2020, compared with 1,569 in April 2019 and 1,441 in 2018. Similarly, the number of claims granted in May 2020 (1,239) was lower compared with 2019 (1,730) and 2018 (1,392).

Figure 4: Number of claims granted for FDV Crisis Payments, monthly, January 2018 to December 2022

| Month | Number of claims |

|---|---|

| Jan 18 | 1,882 |

| Feb 18 | 1,497 |

| Mar 18 | 1,537 |

| Apr 18 | 1,441 |

| May 18 | 1,392 |

| Jun 18 | 1,280 |

| Jul 18 | 1,181 |

| Aug 18 | 1,491 |

| Sep 18 | 1,371 |

| Oct 18 | 1,714 |

| Nov 18 | 1,728 |

| Dec 18 | 1,504 |

| Jan 19 | 1,962 |

| Feb 19 | 1,783 |

| Mar 19 | 1,758 |

| Apr 19 | 1,569 |

| May 19 | 1,730 |

| Jun 19 | 1,360 |

| Jul 19 | 1,346 |

| Aug 19 | 1,528 |

| Sep 19 | 1,582 |

| Oct 19 | 1,778 |

| Nov 19 | 1,837 |

| Dec 19 | 1,763 |

| Jan 20 | 2,201 |

| Feb 20 | 1,989 |

| Mar 20 | 1,965 |

| Apr 20 | 1,337 |

| May 20 | 1,239 |

| Jun 20 | 1,607 |

| Jul 20 | 1,607 |

| Aug 20 | 1,771 |

| Sep 20 | 1,979 |

| Oct 20 | 2,256 |

| Nov 20 | 2,316 |

| Dec 20 | 2,054 |

| Jan 21 | 2,199 |

| Feb 21 | 2,187 |

| Mar 21 | 2,437 |

| Apr 21 | 2,101 |

| May 21 | 2,408 |

| Jun 21 | 2,260 |

| Jul 21 | 2,196 |

| Aug 21 | 2,176 |

| Sep 21 | 2,171 |

| Oct 21 | 2,154 |

| Nov 21 | 2,258 |

| Dec 21 | 2,215 |

| Jan 22 | 2,153 |

| Feb 22 | 2,297 |

| Mar 22 | 2,244 |

| Apr 22 | 1,713 |

| May 22 | 2,229 |

| Jun 22 | 2,280 |

| Jul 22 | 1,858 |

| Aug 22 | 2,279 |

| Sep 22 | 2,067 |

| Oct 22 | 2,179 |

| Nov 22 | 2,422 |

| Dec 22 | 2,271 |

Note:

- Caution should be used when comparing change over time. On 13 June 2020, changes were made to the online claims system, which allowed FDV crisis payment claims to be submitted as an online claim rather than a paper claim form.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

Services Australia customer data (unpublished)

|

Data source overview

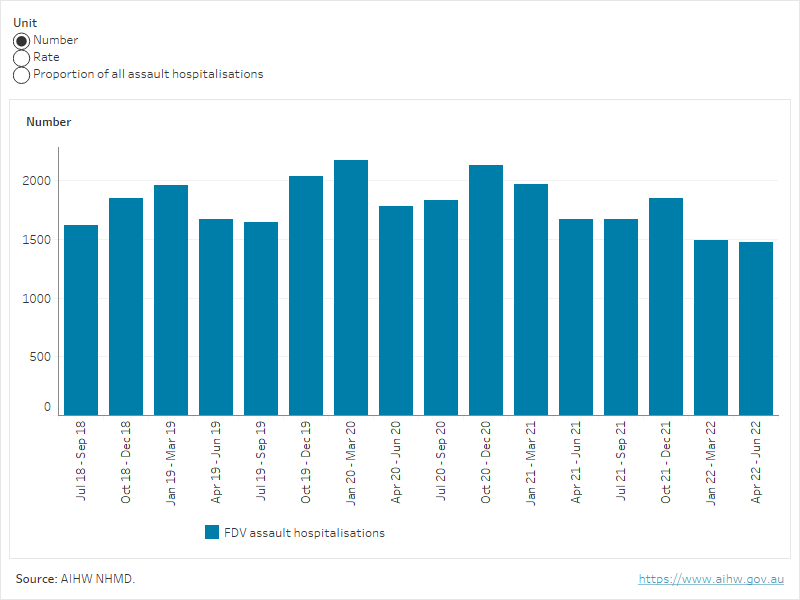

Hospitalisations

People who experience FDV-related assault (assault where the perpetrator was identified as a spouse or domestic partner, or other family member) may be admitted to hospital to receive care (hospitalisations). Data are available from the AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database to report on FDV-related assault hospitalisations, by financial year. However, these data do not include presentations to emergency departments and will relate to more severe (and mostly physical) experiences of FDV (AIHW 2019). For more information, see Health services.

Rates of FDV-related injury hospitalisations fluctuated over time, with some seasonal fluctuations – highest in the October-December and January-March quarters – of each financial year (see Figure 5).

Between July 2018 and June 2022:

- the highest number of FDV-related injury hospitalisations per quarter was 2,174 in the first quarter of 2020 (January – March)

- FDV-related assault injuries made up a greater proportion (38%) of total assault injuries in the second quarter of 2020 (April – June) than in any other quarter (AIHW 2023).

Figure 5: FDV-related assault hospitalisations, 2018–19 to 2021–22

This figure shows that between July 2018 and June 2022 the highest number of FDV-related injury hospitalisations per quarter was 2,174 in the first quarter of 2020.

Police

Police responses to family, domestic and sexual violence are recorded in the ABS Recorded Crime–Victims, 2022 and ABS Recorded Crime–Offenders, 2021–22 collections. These data are not available by month, but the data over a 12-month period can be used to show general patterns in police responses over time. Changes in crime rates may be due to a range of factors, such as changes in reporting behaviour, increased awareness about forms of violence, changes to police practices, and/or an increase in incidents. In the context of the pandemic, research indicates that the likelihood of reporting intimate partner violence to police also varies according to the individual, the relationship, and abuse characteristics (Morgan et al. 2022). For more information, see FDSV reported to police.

Overall, the number of victims recorded by police for sexual assault and FDV-related assault (for the states and territories where data are available) have increased over time. In 2022, the number of victims of sexual assault was the highest number recorded across the 30-year time series. Table 3 shows the number of FDSV-related assaults in 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022. For FDV-assaults overall, the Northern Territory had the greatest percentage increase between 2019 and 2022 (69%), while the ACT showed the only decrease (-0.1%) (ABS 2023b).

| Type of violence | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sexual assault | 26,860 | 27,538 | 31,074 | 32,146 |

FDV-related sexual assault | 8,985 | 10,175 | 11,362 | 11,676 |

FDV-related assault* | 64,969 | 70,028 | 72,461 | 76,862 |

* Data on FDV-related assault are not available for Victoria or Queensland.

Source: ABS (2023b).

Over the same period, the number of FDV offenders proceeded against by police varied across states and territories (see Table 4).

- Between 2018-19 and 2021-22, the number of offenders proceeded against for an FDV-related offence increased across most states and territories, with the greatest overall increases in Queensland (33%) and New South Wales (18%).

- A reduced number of offenders proceeded against by police was recorded in South Australia (-11%) between 2019–20 and 2021–22 and in Western Australia (-9.2%) between 2018–19 and 2021–22 (ABS 2023c).

| 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

NSW | 26,209 | 27,525 | 29,903 | 31,008 |

Vic | 16,210 | 16,925 | 17,448 | 17,169 |

QLD | 13,136 | 13,899 | 15,730 | 17,412 |

SA | np | 4,963 | 4,970 | 4,401 |

WA | 7,636 | 7,588 | 7,417 | 6,930 |

Tas | 1,321 | 1,337 | 1,437 | 1,471 |

NT | 2,672 | 2,605 | 3,080 | 2,919 |

ACT | 554 | 584 | 510 | 565 |

Source: ABS (2023c).

For context, the number of offenders proceeded against Australia-wide for any offence decreased each year since 2018–19. Further, it is important to note that FDV statistics from the ABS Recorded Crime–Offenders collection are experimental, with further assessment required to ensure comparability and quality of data.

Is it the same for everyone?

Looking at the experiences of FDSV across different population groups during the pandemic can help us understand who is most affected. While the impact of the pandemic is not yet fully understood, research in the early stages of the pandemic identified a number of population groups that may be at higher risk of experiencing FDSV during the pandemic.

In May 2020, the AIC published the results of an online survey of 9,300 women aged 18 and over who had been in a relationship in the 12 months prior to the survey (Boxall and Morgan 2021b). The study found several population groups had an increased likelihood of experiencing domestic violence in the 3 months prior to the survey. Select findings are summarised below:

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) respondents were more likely than non-Indigenous respondents to experience physical/sexual violence (4 times as likely) and coercive control (5 times as likely)

Women with a restrictive long-term health condition were more likely than women who did not have a health condition to experience physical/sexual violence (3 times as likely) and coercive control (3 times as likely)

Pregnant women were more likely than other women to experience physical/sexual violence (3 times as likely) and coercive control (2.5 times as likely).

Women aged 18-24 years were more likely than women aged 55 years and over to experience physical/sexual violence (8 times as likely) and coercive control (6 times as likely)

For more information on coercive control, see Coercive control.

Women with higher levels of financial stress were more likely to experience intimate partner violence

In February 2021, the AIC published the results of an online survey of more than 10,000 women aged 18 and over who had been in a relationship in the 12 months prior to the survey. The survey explored the relationship between economic insecurity and intimate partner violence (IPV) (Morgan and Boxall 2022).

The study identified that compared to women who reported low levels of financial stress, those women who reported high levels of financial stress were:

- 3 times as likely to experience physical violence

- 3 times as likely to experience sexual violence

- 2.6 times as likely to experience emotional abuse.

The study also found that compared to women who said their partner was the main income earner or they had comparable income, those women who were the main income earner were:

- 1.7 times as likely to experience physical violence

- 1.6 times as likely to experience sexual violence

- 1.5 times as likely to experience emotional abuse.

More information

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2021a) Labour force, Australia, March 2021, ABS website, accessed 29 March 2023.

ABS (2023a) Personal Safety, Australia, 2021-22 financial year, ABS website, accessed 30 March 2023.

ABS (2023b) Recorded Crime – Victims, 2022, ABS website, accessed 28 July 2023.

ABS (2023c) Recorded Crime – Offenders, 2021-22, ABS website, accessed 30 March 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2019) Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 29 March 2023.

AIHW (2021a) The first year of COVID-19 in Australia: direct and indirect health effects, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 29 March 2023.

AIHW (2021b) Suicide and self-harm monitoring: COVID-19, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 29 March 2023.

AIHW (2021c) Child protection in the time of COVID-19, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 29 March 2023.

AIHW (2021d) Specialist Homelessness Services: Monthly data, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 29 March 2023.

AIHW (2022) ‘Australia’s health 2022: data insights’, Australia’s Health Series 18, catalogue number AUS 240, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 23 March 2023.

AIHW (2023) AIHW analysis of the National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Boxall H and Morgan A (2021a) Intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of women in Australia (Research report, 03/2021), ANROWS, accessed 29 March 2023.

Boxall H and Morgan A (2021b) ‘Who is most at risk of physical and sexual partner violence and coercive control during the COVID-19 pandemic?’, Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice, No 618 February 2021, Australian Institute of Criminology, Australian Government, accessed 23 March 2023.

Boxall H and Morgan A (2022) Economic insecurity and intimate partner violence in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic (Research report, 02/2022), ANROWS, accessed 29 March 2023.

Carrington K, Morley C, Warren S, Ryan V, Ball M, Clarke J and Vitis L (2021) The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Australian domestic and family violence services and their clients, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56:539-558, doi: 10.1002/ajs4.183.

Diemer K (2023) ‘The unexpected drop in intimate partner violence’, The Conversation, accessed 27 April 2023.

DoHAC (Department of Health and Aged Care) (2022) Australia’s biosecurity emergency pandemic measures to end, DoHAC, accessed 16 March 2023.

DoHAC (2023) Travellers from China required to undertake COVID-19 testing before travel, DoHAC, accessed 16 March 2023.

Hand K, Baxter J, Carroll M and Budinski M (2020) Families in Australia survey: Life during COVID-19: Report number 1: Early findings, July 2020, Australian Institute of Family Studies, accessed 29 March 2023.

Hegarty K, McKenzie M, McLindon E, Addison M, Valpied J, Hameed M, Kyei-Onanjiri M, Baloch S, Diemer K and Tarzia L (2022) ‘I just felt like I was running around in a circle’: Listening to the voices of victims and perpetrators to transform responses to intimate partner violence (Research report, 22/2022), ANROWS, accessed 23 March 2023.

Morgan A and Boxall H (2022) Economic insecurity and intimate partner violence in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic, ANROWS, accessed 2 August 2023.

Morgan A, Boxall H and Payne JL (2022) Reporting to police by intimate partner violence victim-survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic, Journal of Criminology, 55(3): 285-305, doi:10.1177/263380762210948.

Morley C, Carrington K, Ryan V, Warren S, Clarke J, Ball M and Vitis L (2021) Locked down with the perpetrator: The hidden impacts of COVID-19 on domestic and family violence in Australia, International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 10(4), doi:10.5204/ijcjsd.2069.

OECD (2021) Health and a glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD, accessed 29 March 2023.

Peterman A, Potts A, O’Donnell M, Thompson K, Shah N, Oertelt-Prigione S and Van Gelder N (2020) Pandemics and violence against women and children (CGD working paper No. 528), Center for Global Development, accessed 29 March 2023.

Pfitzner N, Fitz-Gibbon K and True J (2022) When staying home isn’t safe: Australian practitioner experiences of responding to intimate partner violence during COVID-19 restrictions, Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 6(2):297-314, doi:10.1332/239868021X16420024310873.

Williams G (2020) A safe place to escape family violence during coronavirus [media release], Victoria Government, accessed 29 March 2023.

YourTown (2022) Kids Helpline: 2021 insights report, YourTown, accessed 23 March 2023.

- Previous page Economic and financial impacts