Services responding to FDSV

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

A wide range of services work with victim-survivors, perpetrators and families when violence occurs. Timely and high quality information about these services helps us better understand the actions individuals and services take in the lead-up to violence, after violence has occurred and in the recovery process. Better data can also shed light on the outcomes achieved by those actions.

This page provides an overview of key concepts relating to services responding to FDSV, and discusses how they are used in the AIHW FSDV reporting. Some contributions from people with lived experience are also included on this page to deepen our understanding of how people interact with the service system.

Where do services fit?

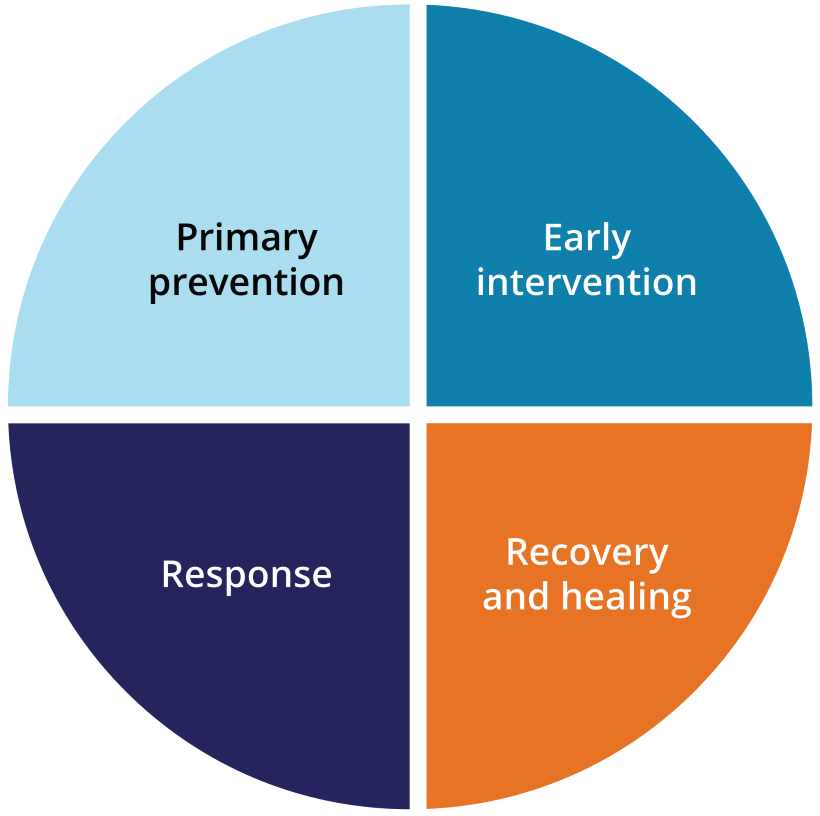

Services responding to FDSV can be seen as part of a broader system of policies and initiatives that work to end violence, by engaging in activities from primary prevention through to recovery and healing (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Understanding the service system using a holistic approach

Note: Adapted from the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032.

Source: DSS 2022.

The four focus areas in Figure 1 recognise that violence exists on a continuum, and ending violence requires a holistic and multi-sectoral approach:

- Prevention means stopping violence from occurring, by addressing its underlying drivers. This requires changing the social conditions that give rise to this violence, and reforming the institutions and systems that excuse, justify or even promote such violence.

- Early intervention, also known as ‘secondary prevention’, aims to identify and support individuals and families experiencing, or at risk of, violence to stop the violence from escalating, protect victim-survivors from harm and prevent violence from reoccurring.

- Response refers to efforts and programs used to address existing violence, for example services such as crisis risk assessment and safety planning, accommodation, counselling, financial, legal or medical assistance as well as police and justice responses, family law services and perpetrator interventions. Also known as ‘tertiary prevention’, these efforts aim to prevent the reoccurrence of violence by supporting victim-survivors and holding perpetrators of violence to account.

- Recovery refers to the ongoing process that aims to assist victim-survivors. Recovery services support victim-survivors to be safe, healthy and resilient, to have economic security, and to have post-traumatic growth. This support helps victim-survivors to recover from the financial, social, psychological and physical impacts of violence. Recovery helps to break the cycle of violence and reduce the risk of re-traumatisation. Recovery also relates to the broader rebuilding of a victim-survivor’s life and ability to return to the workplace and community, obtain financial independence, and economic security.

What services are included in AIHW reporting?

For the AIHW FDSV reporting, the services in focus are those that engage directly with victim-survivors, perpetrators and families when FDSV has occurred. These services fall primarily under ‘responses’ in Figure 1, but may include activities that support victim-survivors in their recovery, or prevent violence from reoccurring (early intervention). Community-wide initiatives – that focus on prevention and early intervention – are not in scope for the AIHW FDSV reporting. Narrowing the scope of initiatives to those that engage individuals directly, enables us to adopt a person-centred approach to reporting on the FDSV service system. It also enables us to better understand the experiences of people engaging with services, so that we can build the evidence base around service use, which can improve service planning and delivery.

In Australia, primary prevention initiatives are currently being led by Our Watch, who work to embed gender equality and prevent violence where people in Australia live, learn, work and socialise. Our Watch also work to build the evidence base around primary prevention, by developing frameworks, academic papers and research and undertaking evaluations. This work complements the AIHW FDSV reporting, and more information can be found on the Our Watch website.

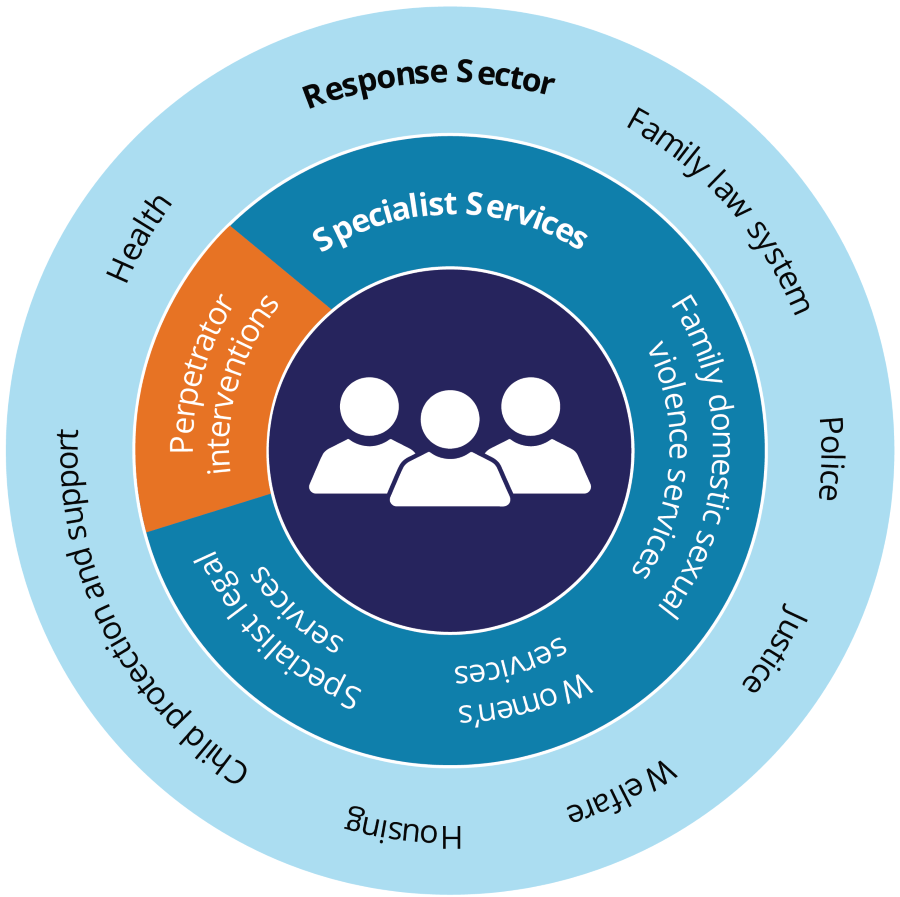

What are the different types of services responding to FDSV?

Services responding to FDSV are broad and span multiple sectors. In general, these services can be broken up into ‘specialist’ and ‘mainstream’ services (Figure 2):

- Specialist FDSV services are those that are specifically designed to assist people who experience or use FDSV. The services provided can vary, but in general, they assist and support victim-survivors, perpetrators, and others affected by FDSV, by providing short- and longer-term responses.

- Mainstream services refer to services available in the community that may be accessed by someone experiencing FDSV. These services may have a broader scope than FDSV, and can include health and welfare, and justice services.

Figure 2: Services responding to FDSV

Note: Adapted from the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032.

Every individual’s pathway through the service system is unique. At different stages, a person may access both mainstream and/or specialist services depending on their needs.

Which services have you found most helpful?

'The referral service was incredibly helpful with information about creating a safety plan and giving me information on things I would need to do before I left, to ensure the safety of me and my son. They also recommended a good removalist who was sensitive to my needs and understood the danger we might be in. My GP was also essential in looking after my mental health during that really stressful period and beyond.'

Martina

'I undertook some creative art therapy with other victim-survivors, which was incredibly powerful and healing. With a friend of mine, who is also a victim-survivor, I developed a group for women who have experienced trauma, to create and write music. I have also been doing work for WEAVERS and have now been appointed to a government victim-survivor advisory council. I guess I have channelled my healing into practical ways to help others and hopefully raise awareness and increase prevention.'

Martina

Specialist FDSV services

Specialist FDSV services are specifically designed to assist people experiencing FDSV. In some cases, a single organisation may provide specialist FDSV services only, or specialist FDSV services along with other services (for example, alcohol and other drug treatment services).

Some examples are:

- specialist FDV crisis and/or longer-term support services (including perpetrator services and services dedicated to specific groups, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people)

- specialist sexual violence crisis and/or longer-term support services

- specialist helplines/online services

- specialist family and domestic violence legal and/or court services.

Mainstream services

Mainstream services include a broad range of services available in the community to those who have experienced violence. Mainstream services can sometimes be separated into health and welfare services, and justice and legal services. This distinction can be useful for understanding the different pathways that an individual might take through the service system. It also recognises that justice and legal processes may be different from processes used in health and welfare services, as they operate within legislative frameworks.

| Health and welfare services | Justice and legal services |

|---|---|

|

|

What does it mean to feel supported by services?

'I think services should be more flexible in how we can engage, letting us set the pace of our work and letting us choose what we want to work on. We know our situations best and are the wisest in finding out own solutions to move forward.'

Anonymous

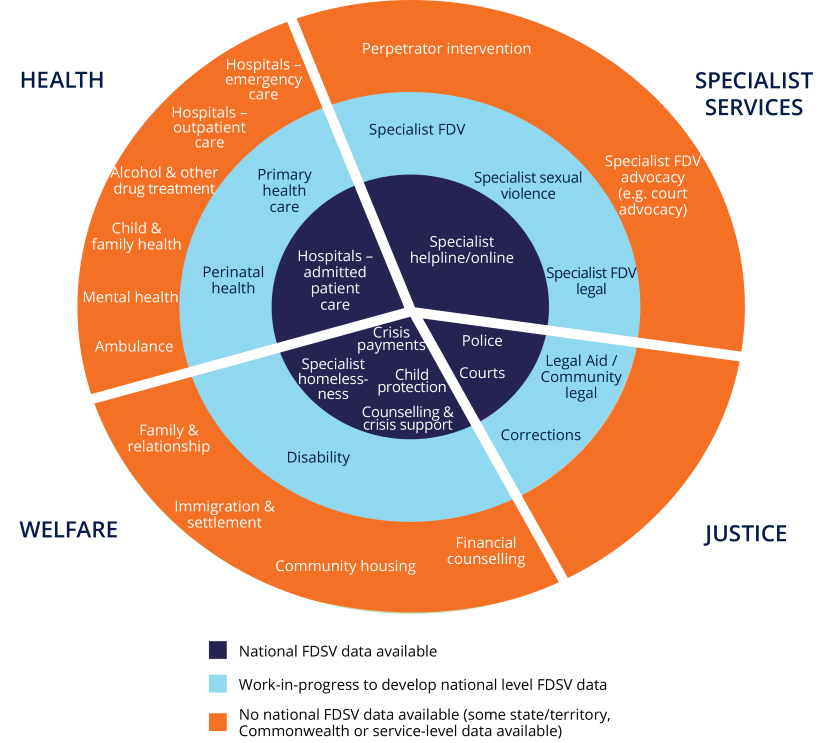

What data are available?

National data are available to report on the FDSV service system across these key areas:

- child protection

- specialist homelessness services

- health services

- police

- legal responses

- helplines.

While these data provide valuable insight into patterns in service use, it is important to acknowledge that a large proportion of people who experience FDSV may not disclose violence to anyone, and may not come into contact with services. According to the 2021–22 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey, many people did not seek advice or support following an incident of partner violence. Of those who had experienced physical and/or sexual violence from a previous cohabiting partner, almost 2 in 5 women (37% or 574,000) and 2 in 5 men (39% or 166,000) did not seek advice or support from anyone. Further, support and advice was more likely to be sought from a family member or a friend than from any formal services – almost 1 in 2 women (45%, or 682,000) and 1 in 2 men (51% or 218,000*) who had experienced violence from a previous partner sought advice or support from a friend or other family member (ABS 2023).

The data available on FDSV services are only part of the picture, and should be brought together with other sources (such as prevalence surveys) to build a more comprehensive understanding of FDSV. For more information, see How are national data used to answer questions about FDSV?.

- ABS Criminal Courts

- ABS Recorded Crime, Victims

- ABS Recorded Crime, Offenders

- AIHW Child Protection

- AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

- AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Collection

- Department of Social Services – 1800RESPECT

- Services Australia customer data – Crisis payments

For more information about these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

Data gaps and development opportunities

There are many areas within the FDSV service system where data gaps remain. Figure 3 shows where national data are currently available, where the gaps are, and where some work is underway to develop national FDSV data.

Figure 3: FDSV data availability across services

Further, there is currently limited national data about:

- service quality and client experiences

- service outcomes

- service integration.

Improved service data can be used to improve response strategies. However, service data can only relate to those people using the services and cannot answer questions about the level of unmet demand or barriers to access. While data on specialist FDSV services are limited, however work is currently underway to develop a prototype specialist crisis FDV services data collection. For more information about this work, and about data gaps and development across FDSV more broadly, see Key information gaps and development activities.

ABS (2023) Partner violence, ABS website, accessed 7 December 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2022) National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 6 January 2023.

- Previous page Key findings

- Next page How do people respond to FDSV?