FDV reported to police

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

Police may be contacted following an incident of family and domestic violence (FDV). This can be done by a victim-survivor, witness or other person and, if considered a criminal offence, may be recorded as a crime by police. The ABS collects data on selected FDV crimes recorded by police in the Recorded crime – Victims and Recorded crime – Offenders collections (see Box 1). However, not all FDV crimes are reported to police and Recorded Crime data are an underestimate of FDV crimes and identified offenders. Further, not all FDV behaviours are considered criminal offences, and FDV offences will vary according to state and territory. This section discusses select FDV offences that are included in ABS Recorded Crime collections.

What do we know about reporting family and domestic violence to police?

The National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032 (The Plan) highlights that, despite increasing awareness and readiness to talk about FDV, work is needed to remove barriers to reporting to police for victim-survivors (DSS 2022).

A 2022 review of research on police responses found that short-term police responses, such as attendance at a FDV incident, can increase reporting of future FDV and reduce FDV re-offending, and that protection orders and arrests improve victims’ and survivors’ perceptions of safety. It is unclear from the currently available research how arrests affect perpetrator re-offending and what factors influence the effectiveness of arrests in reducing re-offending (Bell and Coates 2022; Dowling et al. 2018).

Rates of reporting FDV to police have historically been negatively impacted by a range of factors including: fear of repercussions; misconceptions about what constitutes a crime; mistrust of police; concerns relating to the misidentification of the perpetrator; concerns relating to being believed and having to relive the experience; past negative experiences with police; institutional violence at the hands of police for some population groups; and barriers to accessing police, such as knowledge and understanding, geographical location and specific population group characteristics (ABS 2017; Douglas 2019; DSS 2022; Voce and Boxall 2018).

Reports into women and girls’ experiences with the police and broader criminal justice system, such as the Queensland Hear her voice reports and the National Plan Victim-Survivor Advocates Consultation Final Report, acknowledge that work has been undertaken to improve police understanding of family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV) and police responses to reports of gendered violence in recent years. However, they also highlight responses are still inadequate and lacking in consistency (Fitz-Gibbon et al 2022; Queensland Government 2022). Reports such as these also highlight the need to improve police response for those victim-survivors who experience intersecting forms of inequality and discrimination, for example, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people, culturally and linguistically diverse people, people with disability, and LGBTIQA+ people, see Population groups (Fitz-Gibbon et al 2022; Queensland Government 2022). The Plan indicates that enhanced education and training of police in terms of responses to reporting of gendered crime and improved access to safe and/or alternative reporting options should be implemented to improve reporting experiences (DSS 2022).

To understand the current extent of police involvement in FDV crimes in Australia, data on level of reporting to police, available from the ABS Personal Safety Survey (PSS) should be examined alongside recorded crime data (ABS Recorded Crime – Victims and ABS Recorded Crime – Offenders). For more information about these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

Police-recorded FDV data are an underestimate of FDV-related offences

Examining whether or not police are contacted following family and domestic assault can provide an indication of reporting levels and utilisation of police services. Data on whether police were contacted (by the victim-survivor or another person) after an experience of family and domestic assault, as well as reasons for not contacting, are available from the ABS PSS. In the PSS, victim-survivors are referred to as people who have experienced violence, see What is family, domestic and sexual violence for more details.

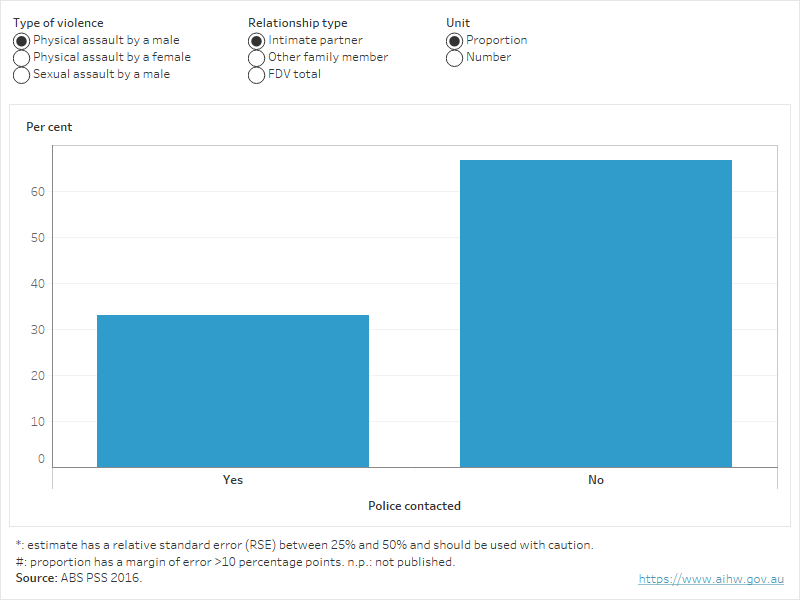

The 2016 PSS includes data on most recent incidents of physical and/or sexual assault by a family member or intimate partner in the last 10 years. AIHW analysis of these data for female victim-survivor found that police were contacted in relation to around:

- 1 in 3 (32% or 278,000) FDV-related physical assaults by a male

- 1 in 6 (17% or 18,100) FDV-related physical assaults by a female

- 1 in 7 (14% or 50,100) FDV-related sexual assaults by a male (ABS 2017).

Figure 1 allows users to further explore police contact by relationship types. Data for females who experienced sexual assault by a female and males who experienced any type of FDV assault and are not available due to data quality issues, see Data sources and technical notes.

Figure 1: Police contacted after most recent incident of family and domestic assault, females, 2016

Figure 1 shows the proportion and number of females that contacted police after their most recent incident of family and domestic assault in 2016.

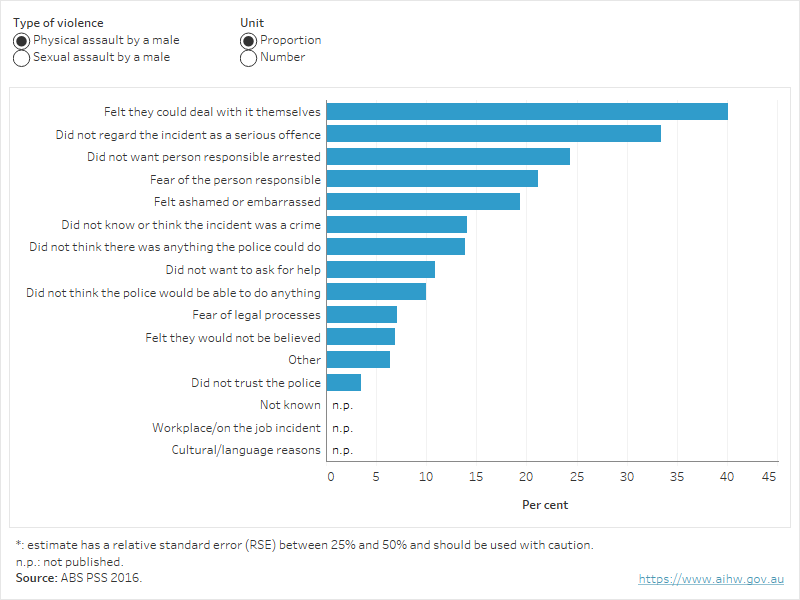

Examining reasons why people did not contact police after family and domestic assault can provide insight into how victim-survivors can be better supported and encouraged to seek help. There are a range of reasons why female victim-survivors may not contact police following their most recent incident of FDV assault by a male perpetrator in the last 10 years. AIHW analysis of the 2016 PSS found that the 2 most common reasons female victim-survivors did not contact police were:

- they felt like they could deal with it themselves (40% of those who experienced physical assault and 33% who experienced sexual assault)

- they did not regard the incident as a serious offence (33% of those who experienced physical assault and 35% who experienced sexual assault) (Figure 2) (ABS 2017).

Data for males and some violence types are not available due to data quality issues, see Data sources and technical notes.

Figure 2: Reasons police not contacted after most recent incident of family and domestic assault, females, 2016

Figure 2 shows the proportion and number of females that did not contact police after their most recent incident of family and domestic assault in 2016, sorted by the reasons police was not contacted.

What do recorded crime data tell us?

-

More than 1 in 2 (53% or 76,900) police-recorded assaults in 2022 were related to FDV nationally (excluding Victoria and Queensland)

Source: ABS Recorded Crime - Victims

The ABS collects data on a select range of offences recorded by police, including FDV incidents, and publishes these in the Recorded crime – Victims and Recorded crime – Offenders collections (see Box 1). These collections provide insight into police involvement in a subset of FDV incidents in the Australian community and the magnitude of FDV crimes relative to select crimes overall.

ABS Recorded Crime collections are based on crimes recorded by police in each state and territory and published according to the Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification (ANZSOC) (ABS 2011). Only a select set of crimes are considered for inclusion in the ABS FDV data in the Recorded Crime collections, with individual incidents only included in FDV collections when:

- the relationship of offender to victim falls within a specified family or domestic relationship (spouse or domestic partner, parent, child, sibling, boyfriend/girlfriend or other family member to the offender) and/or

- a FDV flag has been recorded, following a police investigation and does not contradict any recorded detailed relationship of offender to victim information.

FDV specific data are available in both the Victims and Offenders collections, however, data in the Offenders collection are experimental only and assessment is ongoing to ensure comparability and quality of the data. Victims data include each incident of FDV crime that police record (not all crimes are recorded) rather than reflecting a count of unique people. Victims data are not restricted by age and includes incidents of child sexual abuse (see Children and young people). Conversely, Offenders data reflect a count of unique alleged offenders aged 10 and over, irrespective of how many offences they may have committed within the same incident, or how many times police dealt with them during the reference period. Alleged offences recorded in offenders’ statistics may be later withdrawn or not be substantiated. Offenders data include both court or non-court actions (for example warnings, conferencing, diversion). An individual offender may have more than one police proceeding recorded in the same reference period

It is important to note that the number of police-recorded victims does not align with the number of recorded offenders nor the proceeding counts due to different counting rules, different reference periods, and variation in the time between when a crime is recorded and when police identify an offender. In some cases, police may never identify offenders.

Due to differences in methodology, homicide numbers reported in ABS recorded crime collections may differ to those reported by the AIC National Homicide Monitoring Program. For more details, see Domestic homicide.

The terms ‘victim’ and ‘offender’ are used here to align with the ABS recorded crime collections.

For more details, see Data sources and technical notes.

Based on data from Recorded Crime – Victims, in Australia in 2022:

- more than 1 in 2 (53% or 76,900) recorded assaults were related to FDV violence (excluding Victoria and Queensland as data were unavailable), a 6.1% increase from 72,500 in 2021

- more than 1 in 3 (36% or 135) recorded homicides and related offences were related to FDV

- more than 1 in 3 (36% or 11,700) recorded sexual assaults were related to FDV

- around 3 in 10 (30% or 154) recorded kidnapping/abduction were related to FDV (ABS 2023).

Has it changed over time?

-

There was a 51% increase in the victimisation rate of police-recorded FDV-related sexual assault between 2014 and 2022

Source: ABS Recorded Crime - Victims

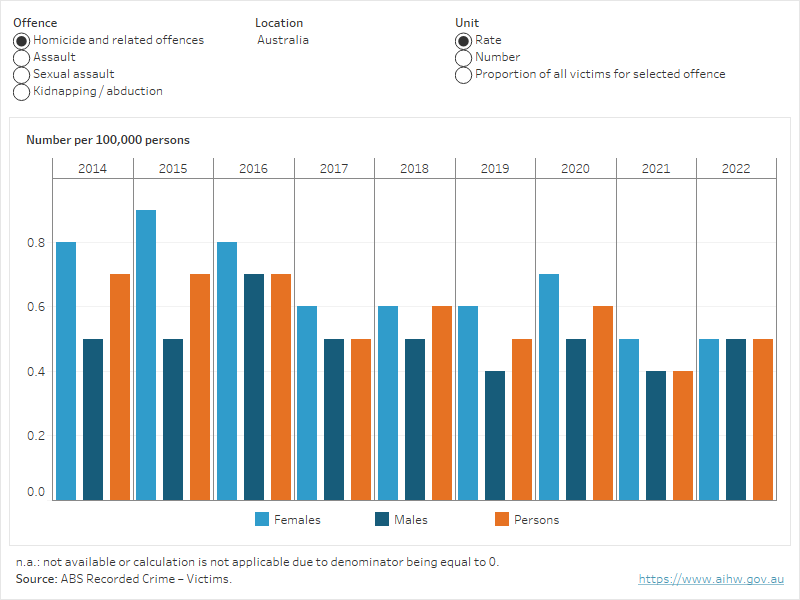

Recorded Crime – Victims data show that in Australia, between 2014 and 2022, patterns of FDV victimisation rates varied between offence types:

- Rates for FDV-related homicide and related offences fluctuated over time, with the number of offences ranging between 106 and 173 each year.

- The rate of FDV-related sexual assaults increased 51% (from 30 to 45 per 100,000 people), with rates consistently higher for females compared to males. It is unclear whether this increase is due to changes in reporting behaviour, increased awareness about forms of violence, changes to police practices, an increase in incidents and/or a combination of these factors.

- Rates for FDV-related kidnapping/abduction fluctuated over time, with the number of offences ranging between 113 and 159 each year.

Figure 3 allows users to further explore victimisation rates over time for selected FDV offences recorded by police per 100,000 people, by sex and location. These rates are based on all recorded incidents of a specific crime irrespective of age. To better understand the relationship between victimisation rates and sex, see Figure 4 and Figure 5. See Data sources and technical notes for more information on rates and definitions of specific offences.

Figure 3: Victims of family and domestic violence crimes, by sex, 2014 to 2022

Figure 3 shows the rate, number and proportion of victims of family and domestic violence crimes by sex from 2014 to 2021.

Is it the same for everyone?

Police recorded FDV offences can be explored in terms of a range of different victim and crime characteristics. Depending on the offence, these can include: sex of victim, state and territory in which the incident was reported, victim age at report, victim age at incident, time to report, setting where the crime occurred and relationship of offender to victim.

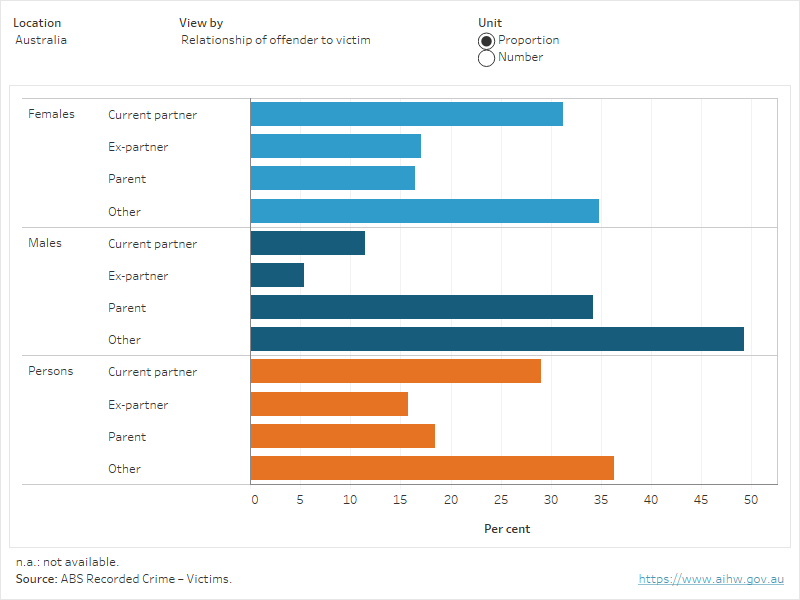

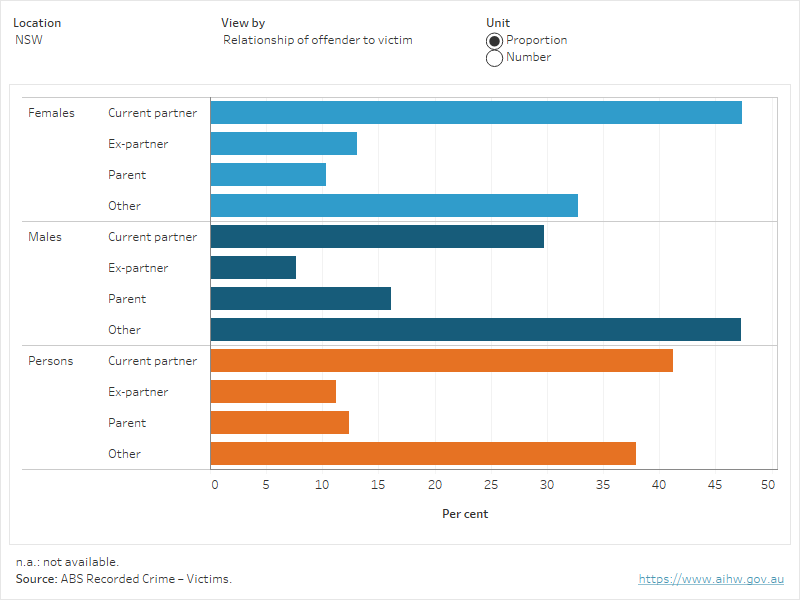

Of all police recorded FDV-related sexual assaults in Australia (excluding Western Australia for data relating to relationship to perpetrator) in 2022:

- 2 in 7 (29% or 3,100) were perpetrated by a current partner and around 1 in 6 (18% or 2,000) were perpetrated by a parent. Relationship data are not restricted to specific age groups and FDV-related sexual assaults involving a parent perpetrator can be broader than incidents of child sexual abuse, see Children and young people. Similarly, other relationship categories may include incidents of child sexual abuse.

- The proportion of female FDV-related sexual assaults perpetrated by a current partner (31%) is 2.7 times higher than for males (12%).

- Around 3 in 5 (62% or 7,200) involved victims aged less than 18 at the time of the incident, with 59% of female and 84% of male victims within this age group.

- Over half (57% or 6,700) were reported within the first year and around a quarter (24% or 2,800) were not reported for five or more years after the incident occurred (ABS 2023).

Figure 4 allows users to further explore the number and proportion of FDV-related sexual assaults recorded by police, by sex of victim, state and territory in which the incident was reported, age at incident, time to report and relationship of offender to victim for 2020 and 2022. For more information on these disaggregations, see Data sources and technical notes.

Figure 4: Characteristics of family and domestic violence-related sexual assaults, 2022

Figure 4 shows the characteristics of victims of family and domestic violence-related sexual assaults in 2020 and 2021.

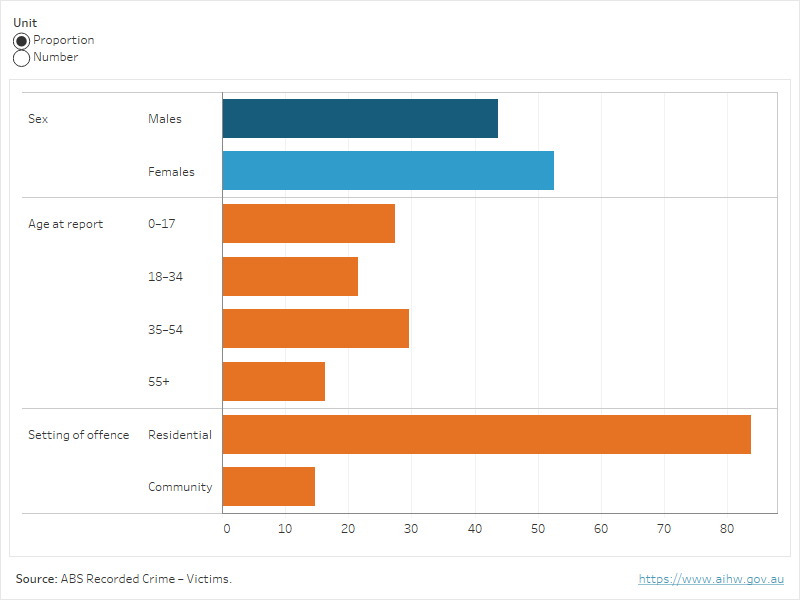

In 2022, for states and territories where police-recorded FDV-related assault data were available:

- For females, current partners were the most common perpetrators for all states and territories. For males, current partners were only the most common perpetrator in Tasmania and the Northern Territory.

- Victims who were aged 25-34 at the time of report accounted for the highest proportion of all FDV-related assaults.

- The majority of FDV-related assaults occurred in a residential setting (ABS 2023).

Figure 5 allows users to further explore the number and proportion of police-recorded FDV-related assaults by several characteristics (sex of victim, state and territory in which the incident was reported, age at report, setting where crime occurred and relationship of offender to victim). For more information on these disaggregations, see Data sources and technical notes.

Figure 5: Characteristics of family and domestic assaults, 2022

Figure 5 shows the characteristics of victims of family and domestic assaults in 2022.

Figure 6 allows users to explore the number and proportion of family and domestic homicides recorded by police, by several characteristics (sex of victim, state and territory in which the incident was reported, age at report, setting where crime occurred and relationship of offender to victim). It shows that of the 135 homicides recorded by police in 2022:

- over half (53% or 71) were female

- over a quarter (27% or 37) of victims were under 18 years of age

- 5 in 6 (84% or 113) occurred in a residential setting (ABS 2023).

For more information on disaggregations, see Data sources and technical notes.

Figure 6: Characteristics of family and domestic homicide, 2022

Figure 6 shows the characteristics of victims of family and domestic homicide in 2022.

Offenders of FDV

-

51%

The most common principal offence amongst FDV offenders was assault (51% of all FDV offenders) in 2022–23

Source: ABS Recorded Crime - Offenders

The ABS Recorded crime – Offenders, 2022–23 collection includes experimental FDV data. These FDV experimental data show that in 2022–23:

- One in 4 (25% or 88,400) recorded offenders for any offence were proceeded against by police for at least one FDV related offence. The proportion was higher for male offenders (27%) than for female offenders (21%).

- The offender rate was 382 FDV offenders per 100,000 people, an increase of 5.5% from 2021–22.

- The male offender rate (610 per 100,000) was higher than the female offender rate (158 per 100,000).

- Offender rates varied between age groups, with males aged 30–34 having the highest rate (1,158 per 100,000).

- The most common principal offence amongst FDV offenders was assault (51% or 44,700 of all FDV offenders). Breach of domestic violence and non-violence orders was also common (28% or 24,800 of all FDV offenders) (ABS 2024).

Following police charges, individuals may become a defendant in 1 or more criminal court case. For more information on defendants in FDV cases, see Legal systems. FDV offenders may also take part in specialist perpetrator interventions, which work to hold perpetrators to account and change their violent, coercive and abusive behaviours. behaviours. More information can be found in Specialist perpetrator interventions.

Related material

More information

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2011) Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification (ANZSOC), ABS Website, accessed 4 April 2023.

ABS (2017) Personal safety, Australia, 2016, ABS website, accessed 20 September 2022.

ABS (2023) Recorded crime - Victims, ABS Website, accessed 1 August 2023.

ABS (2024) Recorded crime - Offenders, ABS Website, accessed 21 February 2024.

Bell C and Coates D (2022) The effectiveness of interventions for perpetrators of domestic and family violence: An overview of findings from reviews, ANROWS, accessed 20 December 2023.

Douglas H (2019) Policing domestic and family violence. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 8(2):31–49, doi:10.5204/ijcjsd.v8i2.1122.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2022) National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 15 November 2022.

Fitz-Gibbon K, Reeves E, Gelb K, McGowan J, Segrave M, Meyer S, and Maher JM (2022) National Plan victim-survivor advocates consultation final report, Monash University, Victoria, accessed 29 November 2022.

Queensland Government (2022) Queensland Government response to Hear her voice – Report one – Addressing coercive control and DFV in Queensland, Queensland Government, accessed 15 November 2022.

Voce I and Boxall H (2018) ‘Who reports domestic violence to police? A review of the evidence’, Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice, 59, accessed 29 November 2022.

- Previous page FDSV reported to police

- Next page Sexual assault reported to police