Health services

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

In 2021–22:

- 9 in 10 hospitalisations for FDV-related injury by a partner were for females.

- Men were most likely to be hospitalised for a FDV-related injury by a family member other than their partner or parents.

- With the exception of hospital admitted care, national data on other FDSV health service responses are very limited, although some data improvement work is underway.

Health services play an important role in responding to family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV) (Garcia-Moreno et al. 2015). The 2021–22 ABS Personal Safety Survey (PSS) estimated that 1 in 5 women who experienced violence from a current partner sought advice or support from a general practitioner or other health professional (ABS 2023) (see How do people respond to FDSV?). It is also estimated that a full-time GP sees around five women per week who have experienced intimate partner violence in the last 12 months, representing an opportunity for early intervention and ongoing support (Roberts et al. 2006, as cited in RACGP 2022).

There are also financial costs, at both the health system and individual level. The health system cost associated with treating the effects of any violence against women was estimated to be at least $1.4 billion in 2015–16 (KPMG 2016). In addition, an analysis of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health found that:

- women with a history of intimate partner violence (IPV) have $48,413 higher lifetime health costs per person than women who do not experience IPV (William et al. 2022)

- the predicted average annual Medicare costs for women born in 1989–1995 who had experienced sexual violence were between $200 and $268 higher than for those who had not experienced sexual violence (Townsend et al. 2022)

- women born in 1989–1995 who had experienced sexual violence (22%) were more likely to have used at least one mental health consultation in 2018-19 when compared with women who had not experienced sexual violence (14%) (Townsend et al. 2022).

Examination of data on health service responses related to FDSV can provide insight on the use of different services, the extent and nature of violence experienced, and opportunities for intervention.

What do we know?

Australia’s health services include a complex mix of service providers and health professionals that collectively work to meet the health care needs of people in Australia. These services can assist victim-survivors and/or perpetrators of violence in a range of ways (Box 1).

Health services that respond to FDSV may include:

- primary care, including general practitioners (GPs) and community health services

- mental health services

- ambulance or emergency services

- alcohol and other drug treatment services

- hospitals (admitted patient care; emergency care; and outpatient care).

The type of interaction that victim-survivors and/or perpetrators have with these services will vary depending on the scope and aims of the service. Health services can assist in a range of ways including routine screening for domestic violence, risk assessment and safety planning, counselling, care and treatment for injuries due to FDSV, and first line responses, such as providing information and support.

To provide more holistic care for a person experiencing FDSV, some health services partner with other services to provide additional support in one physical location, for example health justice partnerships where health professionals and legal professionals work together at a hospital or health centre (AGD 2022).

Measuring health service use for FDSV

While each health service response has an important and different role to play, national service-level data on responses to FDSV are limited. Hospital records related to episodes of admitted care (hospitalisations) are the main nationally comparable data available, although some data related to FDSV responses in other health services are available in some states and territories. For this reason, national hospitalisation data from the AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database are a focus of this topic page (for more information about this data source, please see Data sources and technical notes). However, information about other health services, such as primary care, including antenatal care, and ambulance services, are also discussed in the context of data development opportunities.

Even where service-level data related to FDSV are available, it is important to note that these data will not represent the complete picture as people may not always seek assistance, or when they do, they can be reluctant to disclose information related to violence involving a family member, or intimate partner. Additionally, personal accounts from service workers indicate a lack of resources and education may prevent adequate identification, treatment and documentation of victim-survivors engaging with health services (Cullen et al. 2022).

What do the data tell us?

Hospitals

Some people who experience family and domestic violence are admitted to hospital for treatment and care. The AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database captures the number of cases admitted to hospital with an injury related to FDSV. Examining the number of hospitalisations for injuries related to FDV provides an indication of the demand for these services. However, these data do not include presentations to emergency departments and will relate to more severe (and mostly physical) experiences of family and domestic violence (FDV) (AIHW 2019; AIHW 2022a).

The 10th Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) is an international standard for coding of diseases and related health conditions developed by the World Health Organization (WHO). The Australian modification of the ICD-10 (ICD-10-AM) is used to classify episodes of hospital care including those where family, domestic and sexual violence is documented in the hospital record.

Coding captures a broad scope of injuries which could include physical, sexual and psychological abuse. FDV data are recorded using the following coding rules:

- a perpetrator coded as Spouse or domestic partner, Parent, or Other family member and,

- an injury principal diagnosis in the ICD-10-AM code range S00–T75, T79,

- a first recorded External causes of morbidity and mortality ICD-10-AM code in the range X85–Y09 (Assault).

Using this method there were 6,478 hospitalisations in 2021–22. If the method is expanded to include hospitalisations with FDV assault recorded as any external cause regardless of the principal diagnoses, then the number of hospitalisations increases by 25% (to 8,086). Of these 8,086 hospitalisations, 83% have a principal diagnosis related to injury and poisoning, and 5% have a principal diagnosis related to mental and behavioural disorders. Regardless of the method used, around 3 in 4 hospitalisations where FDV assault was documented were for females (AIHW 2023a).

Improvements in recording of perpetrator

Specific information about a perpetrator may not be available in assault hospitalisations for a number of reasons, including:

- information not being reported by, or on behalf of, victims, or

- information not being recorded in the patient’s hospital record.

Additionally, the perpetrator of assault was less likely to be specified for:

- male victims when compared with female victims; young or middle-aged adults when compared with children and older victims (AIHW 2021).

However, the proportion of assault hospitalisations with a specified perpetrator recorded has improved by almost 25 percentage points from 42% in 2002–03 when perpetrator coding was introduced, to 67% in 2021–22 (AIHW 2023a).

-

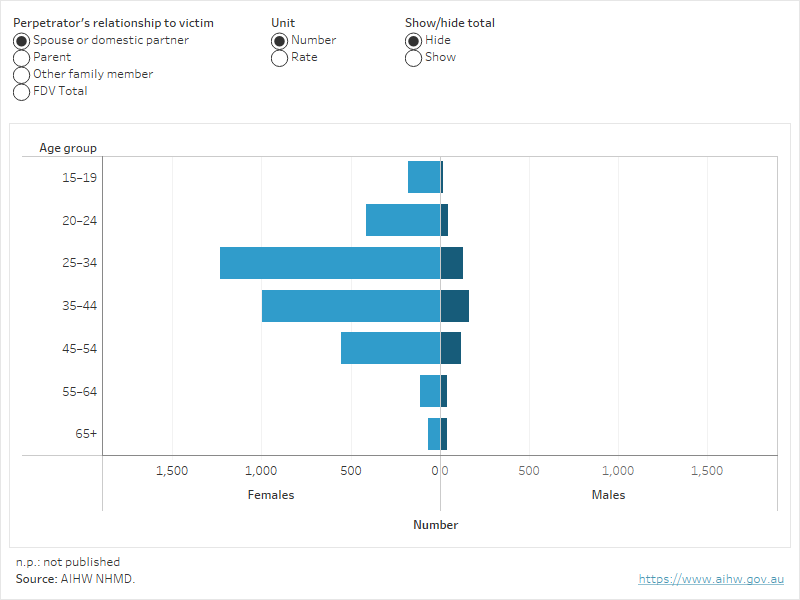

In 2021–22, 9 in 10 hospitalisations for assault injury by a partner were for females

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

In 2021–22, 3 in 10 (32% or 6,500) assault hospitalisations were due to FDV. The overall rate of FDV hospitalisations was almost 3 times as high for females compared with males (Figure 1). Across all age groups, the number and rate of FDV hospitalisation were greater for females than males aged 15 and older.

Almost 9 in 10 (87%) hospitalisations due to injury from a spouse or domestic partner involved a female. Rates of hospitalisation where the perpetrator was a spouse or domestic partner were 6 times as high for females (33 per 100,000) than males (5.3 per 100,000) aged 15 and over.

These rates increased with age for younger females, peaking at age 25–34 (66 per 100,000), and then decreased with age to 2.8 per 100,000 for females aged 65 and over. Similarly, the rate of hospitalisations for assault by a spouse or partner increased with age for males, and was highest in 35–44 year olds (9.3 per 100,000), decreasing to 1.8 per 100,000 for males aged 65 or older (AIHW 2022a). See also Young women.

Figure 1: Family and domestic violence hospitalisations by relationship to perpetrator and age, 2021–22

Figure 1 allows users to explore the rate of family and domestic violence hospitalisations by relationship to perpetrator and sex, across age groups.

-

In 2021–22, men were more likely to be hospitalised for a family and domestic violence related assault injury by someone other than a partner or parent

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

In 2021–22, the majority (59%, or 930) of FDV hospitalisations for males aged 15 and over were for injuries from a family member other than their spouse or domestic partner or parent.

The rate of hospitalisations for males for assault by a family member (other than a partner or parent) was highest for 20–24 year olds (13 per 100,000), and decreased with age to 4.9 per 100,000 for males aged 65 years or older. The rate of females hospitalised for assault by other family members was highest for women aged 20–24 and 25–34 (each 12 per 100,000) and decreased with age to 4.1 per 100,000 for females aged 65 years or older (Figure 1).

Hospitalisations over time

-

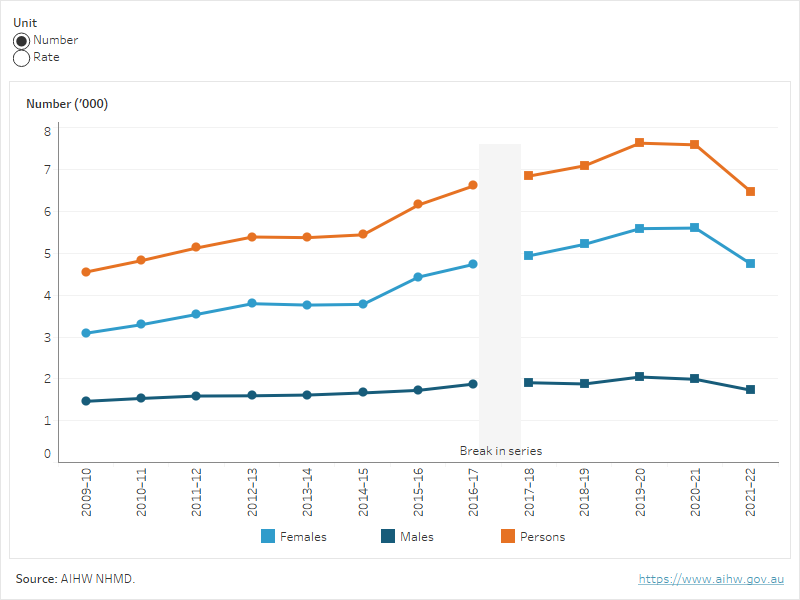

Between 2020–21 and 2021–22, the rate of family and domestic violence hospitalisations for females fell by 15% and the rate for males remained relatively stable

AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

While examining hospitalisations over time can help to understand patterns of hospitalisations for FDV related cases, it does not represent the broader prevalence of FDSV across the population in Australia. Changes in hospitalisation rates may be due to changes in disclosure rates, changes in identification or recording of family and domestic violence by health professionals, and/or changes in family and domestic violence events requiring hospitalisation (AIHW 2022a).

Between 2020–21 and 2021–22 the rate of family and domestic violence hospitalisations for females decreased by 15% and the rate for males remained relatively stable. This is consistent with the data for all injury hospitalisations in 2021–22 – for information about the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on injury hospitalisations, see Injury in Australia. Characteristics of FDV-related injury hospitalisation in 2021–22 were relatively consistent when compared with 2020–21 (for example, the vast majority of hospitalisations were for females and most injuries were to the head) (AIHW 2023a).

For data relating to FDV-related injury hospitalisations during the COVID-19 pandemic, see FDSV and COVID-19.

Figure 2: Family and domestic violence hospitalisations, by sex, 2009–10 to 2021–22

Figure 2 allows users to explore the rate of family and domestic violence hospitalisations, by sex over time.

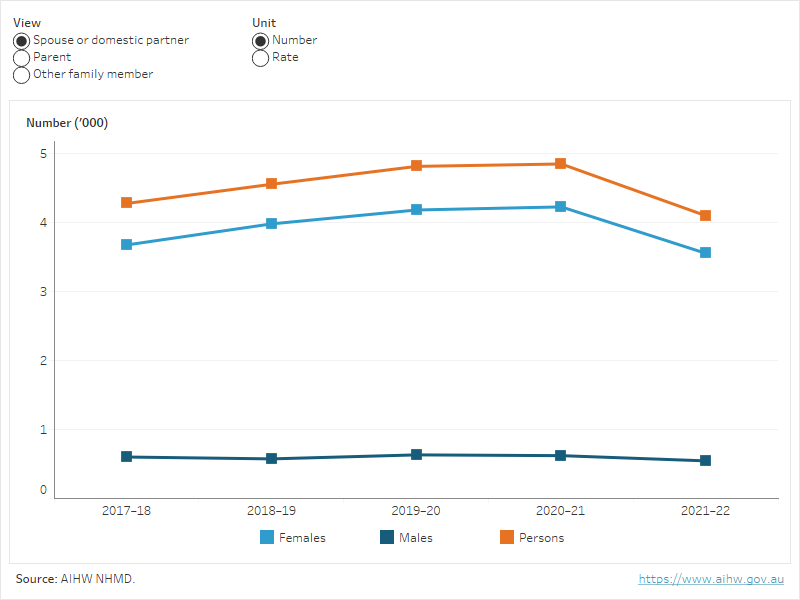

The visualisation below allows users to explore the rate of family and domestic violence hospitalisations by relationship to perpetrator and sex, over time. Rates of hospitalisation where the perpetrator was a spouse or domestic partner were consistently around 6 times higher for females aged 15 years and over than for males (AIHW 2023a).

Figure 3: Family and domestic violence hospitalisations, by relationship to perpetrator, 2017–18 to 2021–22

Figure 3 allows users to explore the rate of family and domestic violence hospitalisations by relationship to perpetrator and sex, over time.

Is it the same for everyone?

Select population groups may be exposed to intersecting and unique challenges that impact rates of hospitalisation for FDV related injury. Investigating the prevalence of FDV in specific groups can be used to inform the development of more targeted and needs-based programs and services.

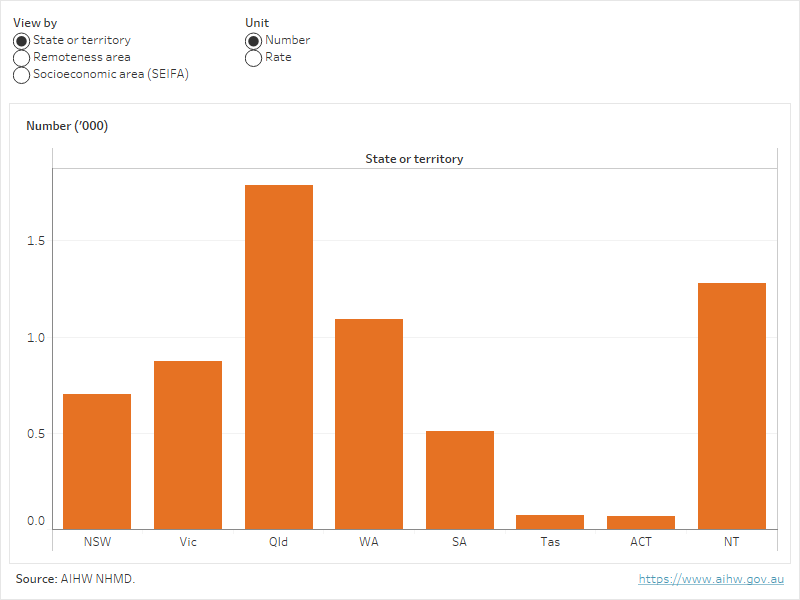

The visualisation below (Figure 4) allows users to explore the rate of family and domestic violence hospitalisations, by various population groups for which national data were available. In 2021–22, rates of family and domestic violence hospitalisations:

- were highest for those living in the Northern Territory

- increased with remoteness

- were highest for those in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic area compared with all other socioeconomic areas (AIHW 2023a).

Figure 4: Family and domestic violence hospitalisations, for select population groups, 2021–22

Figure 4 allows users to explore the rate of family and domestic violence hospitalisations, by select population groups.

Rates of family and domestic violence hospitalisations were also higher for First Nations people than non-Indigenous people. See Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

For more information on specific groups see Population groups.

What else do we know about hospitalisations?

Hospitalisations for sexual assault

In 2021–22, there were 280 hospitalisations due to sexual assault (any perpetrator type). The vast majority of people hospitalised for sexual assault were female (93% or 260). Almost 3 in 10 (29%) people hospitalised for sexual assault were aged 25–34, followed by around 1 in 6 people aged 15–19 (17%), 20–24 (16%) and 35–44 (16%) (AIHW 2023a).

Of the 280 sexual assault hospitalisations, the most common perpetrator was an “Unspecified person” (27% or 76). Almost 1 in 4 (23%) females reported a “Spouse or domestic partner” as the perpetrator while no males reported this category of perpetrator (AIHW 2023a).

The number of sexual assault hospitalisations was relatively stable between 2017–18 and 2021–22, with between 220 and 280 hospitalisations recorded each year. Each year from 2017–18 to 2021–22:

- females made up between 89–93% of sexual assault hospitalisations

- 25–34 year olds were the largest age group, ranging from 25–32% of sexual assault hospitalisation cases.

These data do not include any hospital activity in the emergency department or hospital outpatient units.

Analysis using linked data

The AIHW report, Examination of hospital stays due to family and domestic violence 2010–11 to 2018–19 used linked data in the National Integrated Health Service Information Analysis Asset (NIHSI AA) to provide novel analysis of person-level, rather than episode-level data. In addition to providing hospital stay information at the person- level, through the use of linked records, the report also provided insight into emergency department presentations and subsequent deaths among the FDV cohort.

For the linkage report, an FDV hospital stay was defined as any hospital stay where FDV was identified anywhere within the record – that is, including information within additional diagnoses, and not limited to principal diagnosis information. A hospital stay within the report also refers to a continuous episode of care, which can include several hospitalisations.

The number of people who had an FDV hospital stay increased over time

The number of people who had their ‘first’ (first identified in the data) FDV hospital stay between 2010–11 and 2017–18 steadily increased each year, and was 32% higher in 2017–18 compared with 2010–11. However, some people may have had their first stay prior to this period. The total number of FDV hospital stays that occurred each year also increased over the same time period (up 50% by 2017–18) (AIHW 2021).

The increase in ‘first’ FDV hospital stays, and the increase in FDV hospital stays overall may be due to:

- increased disclosure of FDV in hospitals (as a result of increased awareness and/or changes in attitudes), and/or

- increased identification and recording of FDV by health professionals (for example, through screening tools and/or increased training and awareness), and/or

- increased FDV-related events requiring hospitalisation (AIHW 2021).

Hospital data shows a proportional decrease in ‘other’ assaults (i.e. assaults where no perpetrator was specified) over the analysis period. This suggests that ‘other’ assaults may have proportionally decreased due to increased identification of FDV assault (i.e. an increase in identification of an FDV defined perpetrator) (AIHW 2019; AIHW 2021).

More than 1 in 10 people with an FDV hospital stay had been admitted 2 or more times

Of the people who had at least one FDV hospital stay from 2010–11 to 2017–18:

- 88% had one FDV hospital stay

- 9% had 2 FDV hospital stays

- 3% experienced 3 or more hospital stays for FDV in the time to 2018–19 (AIHW 2021).

These results remain consistent when looking at a 3-year follow-up period; 89% had one FDV hospital stay, 8% had 2, and 2% experienced 3 or more. The most common timeframe between FDV hospital stays for those that had multiple FDV hospital stays, was less than 1 year (62%), followed by 1–2 years (16%). People with 3 or more FDV stays were the most likely to have had 10 or more ED presentations (53%). From the national data, it cannot be determined whether these presentations were FDV-related (AIHW 2021).

For more information on long-term impacts of FDSV see Health outcomes.

Other health services and national development opportunities

National data from health services are essential for understanding the extent, nature and impact of family, domestic and sexual violence. The importance of building a nationally consistent and robust data framework was emphasised in the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children, 2022–2032 and the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence (the Inquiry). The Australian Government supported in-principle, the Inquiry’s recommendation that a ‘data collection on service-system contacts with victim-survivors and perpetrators, including data from primary care, ambulance, emergency department, police, justice and legal services’ be developed, in recognition of the important role of the health system response. A strong evidence base is essential to support and inform policy makers, service providers and government programs that address FDSV (AIHW 2022b, DSS 2023). The AIHW is developing a FDSV integrated data system, which can form the basis for further expansion and development. However, the true value of this system will only be realised when consistent data on FDSV specialist services are available nationally. For more see Family, domestic and sexual violence: National data landscape 2022.

Primary health care

Primary health care, that can include general practitioners, nurses, Aboriginal Health Workers and allied health professionals, may provide a formal point of contact and care for people experiencing FDSV. As general practitioners are often a person’s first point of contact for health care, they are particularly well-placed to identify, support and refer people experiencing intimate partner violence (RACGP 2022).

The primary health care sector is rich in clinical data and information to support the management of individuals’ health care, however, the availability of data for national population research is limited. Specifically, there is no consistent collection of national data to understand how people use primary care, the conditions managed, health and wellbeing outcomes, and links between other services, such as hospitals or community services. Data are collected through a range of different mechanisms across jurisdictions, primary health networks (PHNs) and services, but not in a uniform and consistent way (AIHW 2022b).

Currently, if information is recorded on FDSV, it is usually recorded in free text fields, in a non-standardised way. Therefore, analysis of free text, using complex computing techniques, provides the most likely opportunity to identify FDSV in primary care. Similar strategies could possibly be applied to other service data, such as emergency departments, to help identify the prevalence of FDSV among service users.

Administrative by-product data collected by the Australian Government in relation to Medicare Benefits Schedule claims is used to report on some primary care activity related to specific areas, such as mental health. However, there are currently no specific claims items under the MBS which could be used to identify activity related to FDSV (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs 2021).

There are some national programs focused on primary health care providers under development. For example, the Australian Government has provided funding for an expansion and extension of the Recognise, Respond and Refer pilot program. This trial aims to improve system responses to FDSV, by recognising the key role primary health care plays within the broader system response to FDSV. The program is being trialled in select Primary Health Networks and provides opportunities to consider the scope and nature of data collected in primary care (TCA 2022).

Additionally, the AIHW is leading the establishment of a National Primary Health Care Data Collection. The work program to achieve this encompasses the development of processes for governance, standards, infrastructure, collection, analysis and reporting of primary health care data within Australia. In the longer term, this work may provide an opportunity to capture FDSV in a standardised way to inform national reporting and monitoring related to FDSV (AIHW 2020b).

Perinatal care

Pregnancy can represent a time of increased risk of exposure to violence for both mothers and babies. Many pregnant people have regular contact with health-care professionals during pregnancy, which presents an opportunity to identify and respond to violence (see Pregnant people).

Screening for FDV during pregnancy occurs in most states and territories, however, a variety of FDV screening approaches are used (AIHW 2015). In 2020, a voluntary family violence screening question (which is defined as including "Violence between family members as well as between current or former intimate partners") was introduced into the National Perinatal Data Collection (NPDC) to identify whether screening for FDV was conducted. Due to the time lag between development, implementation and collection of data by the state and territory perinatal data collections and their inclusion in the NPDC, data are not yet available for reporting (AIHW 2023b).

The AIHW is working with the Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care and states and territories to develop the Perinatal Mental Health pilot data collection. This novel data collection will contain data from antenatal and postnatal perinatal mental health screening conducted in participating public maternity hospitals and maternal and child family health clinics; and some of the screening tools included in the pilot cover data on FDSV risk. Analysis of the pilot data will inform decisions about the appropriateness and feasibility of capturing this information on an ongoing basis (AIHW 2022b).

See also Pregnant people.

Emergency departments

Emergency departments (ED) are a critical point of contact for people who require urgent medical attention. In addition to providing immediate medical treatment, EDs also provide resources and additional services to people experiencing FDSV. Understanding how victim-survivors interact with EDs helps inform policy, resourcing and adequate training to staff effectively manage FDSV-related presentations.

The national emergency department (ED) data collection does not currently capture information on presentations related to family or domestic violence related injuries. Unlike for patients admitted to hospitals, the national ED data contains very little information about the context in which injuries occur (that is the ‘external cause’). While the nature of the injury (e.g. a fracture) is captured, information about the cause of the injury (e.g. assault), the place of occurrence (e.g. home) and the activity underway when the injury occurred is not (AIHW 2022b).

Currently, this gap inhibits understanding of the extent and impact of this issues on both the health system and the population. For example, it is difficult to answer questions about how FDV impacts EDs, or how many times the same person may be interacting with emergency departments because of violence (AIHW 2022b).

Some relevant information on emergency department presentations related to FDV is collected in some jurisdictions, for example Victoria (see Box 3).

In 2018–19, the AIHW, in conjunction with state and territory stakeholders, developed options for enhancing the capture of FDSV in national ED data, and national discussions continue about the options for capturing external cause data more broadly in national ED data (AIHW 2020b).

As more Urgent Care Clinics are established across Australia (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023), it is expected that some patients experiencing FDSV will present at these services instead of emergency departments. Development of the national Urgent Care Clinic data collection may provide an opportunity to capture and report data related to FDSV in the future.

The Crime Statistics Agency (CSA) Victoria captures state data on emergency department responses to family, domestic and sexual violence. The CSA captures incidents where a clinician has indicated one of the following categories has contributed to injury:

- Sexual assault by current or former intimate partner

- Sexual assault by other family member (excluding intimate partner)

- Neglect, maltreatment, assault by current or former intimate partner or

- Neglect, maltreatment, assault by other family member (excluding intimate partner).

From 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2022, 6,900 people presented to a Victorian public hospital emergency department for family violence-related injury:

- Around 2 in 3 (64%) were female

- Around 1 in 4 (27%) were females aged 20–34

- The proportion of females (19%) who experienced injury to multiple body regions was twice as high as males (8.9%)

- Both males (39%) and females (34%) most commonly presented to ED for an injury to the head or face.

The ability to use these data to represent the extent of family violence-related presentations may be limited by the level of detail recorded, victim-survivor unwillingness or inability to seek assistance, or when they do, reluctance to disclose information related to violence involving a family member, or intimate partner.

Source: CSA 2022.

Ambulance services

Ambulance services can respond to health emergencies related to FDSV. Ambulance clinical records have the potential to capture characteristics of FDSV including the type of violence, relationships between victims and perpetrators, and other associated health factors (such as substance use or mental health concerns). Recording accurate data on attendance for FDSV may also help identify repeat incidents, or individuals who may require additional support or intervention (Scott et al. 2020a).

As noted previously, surveillance data on FDSV at a public health level are limited. Ambulance data has the potential to overcome some of the limitations with other data sources. However, ambulance services are run by states and territories – while many states and territories recognise the importance of identifying FDSV incidents, developments to capture national service-level data are required (AIHW 2022b). Box 4 outlines the data available for reporting from the National Ambulance Surveillance System.

The National Ambulance Surveillance System (NASS) is a world-first public health monitoring system providing timely and comprehensive data on ambulance attendances in Australia. The NASS is a partnership between Turning Point, Monash University and state or territory ambulance services across Australia. The NASS collates and codes monthly ambulance attendances data for participating states and territories for self-harm behaviours (suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, death by suicide and intentional self-injury), mental health and alcohol and other drug-related attendances. These coded data are routinely managed by AIHW; and there is potential to expand the system to capture data on FDSV-related attendances (AIHW 2022b).

Pilot use of the Turning Point data, captured FDV-related attendances in Victoria and Tasmania. These attendances are those in which paramedics recorded the third parties involved in the violent incident as an intimate partner (partner, de facto, married, estranged, previous relationship, other romantic relationships) or other family member (other family, extended family, step, foster and adopted family members). For more information about the NASS, please see Data sources and technical notes.

In 2016–17, there were almost 6,300 violence-related ambulance attendances, the majority (61%) of which were identified as community violence, occurring between individuals who are unrelated and may be unknown to each other. This may include violence against professionals such as paramedics or police. One-quarter (25%) were identified as other family violence (OFV) and 19% as intimate partner violence (IPV) (Scott et al. 2020b).

This pilot project demonstrated that routine coding and reporting of a violence module for these data could complement existing health, police, coronial and survey data (Scott et al. 2020a).

Intimate partner violence

- About 4 in 5 (84%) victims of IPV-related ambulance attendances were females.

- The highest proportion of victims were aged 18–29 and 30–39 (30% each).

- The highest proportion of perpetrators for IPV-related attendances were aged over 60 years (26%), followed by 18–29 year olds (24%).

- About 2 in 5 (42%) IPV-related ambulance attendances for victims were primarily for violence only, and 37% involved alcohol and other drugs.

- About 3 in 10 (28%) IPV-related ambulance attendances for perpetrators involved violence and mental health symptoms, with less than 1 in 5 (16%) involving violence only (Scott et al. 2020a).

Other family violence

- For ambulance attendances for victims of OFV, similar proportions were reported for females (51%) and males (49%).

- The highest proportion of perpetrators for OFV-related attendances were aged under 18 years (31%) (Scott et al. 2020a).

Data from Ambulance Victoria captures indicative rates of events involving FDSV attended to by Ambulance Victoria between July 2017 and June 2022. These events have been flagged by attending paramedics as part of the administrative data collected. During this period, events of alleged FDSV were most likely to involve physical violence (84% of events for which the violence type was recorded, compared with less than 10% each for sexual violence, psychological or emotional violence or other violence). For around 3 in 5 (59%) events a partner/spouse was the alleged perpetrator (where the relationship to the perpetrator was recorded) (CSA 2022).

Other selected health services

Mental health

Given the complex interactions between FDSV and mental illness, services that are dedicated to mental health care can play an important role in responding to people who are at risk of or are experiencing violence. Examples of these services include community-mental health care services, residential mental health care services, specialised psychiatric hospital, or ward services; provided by psychologists, psychiatrists and other allied health professionals.

Nationally consistent data on FDSV is not currently available across any of these services. While some information on FDSV is available for people admitted to hospital, it is limited to hospitalisations where an FDV assault has been identified or disclosed (see Box 2).

Some relevant data are available in some jurisdictions. For example, in New South Wales screening for domestic violence is required for women aged 16 years and over who attend publicly-funded mental health services and data are available on screening uptake and the outcome (NSW Health 2023).

Alcohol and other drug treatment services

People who are at risk of or experiencing violence may use services dedicated to treatment for alcohol and/or other drug use. Examples of these services include alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment services, and services provided in alcohol and other drug hospital treatment units.

The Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services National Minimum Data Set collects information on the majority of publicly-funded AOD treatment services. This data set does not collect specific information on FDSV, however some relevant data are collected in some states and territories. For example:

- In Queensland, three flags can be recorded in the AOD sector: experiencing family or domestic violence; experiencing family or domestic violence (Domestic Violence Order); and experiencing domestic or family violence (police protection needed) (AIHW 2020a).

- As per mental health services, New South Wales domestic violence screening is required for women aged 16 years and over who attend publicly-funded alcohol and other drug services, and data are available on screening uptake and the outcome (NSW Health 2023).

Specialist sexual violence services

Health-related specialist sexual violence services are usually provided by specialist sexual assault service providers or designated wards/units within hospitals. These services respond to sexual assault by any perpetrator, including domestic and family members, and include medical and forensic sexual assault care, counselling and support, information and referrals. Services and/or interventions may target particular populations, for example, adults, children, victims and survivors of child sexual abuse.

Nationally consistent data on these services is not currently available, although some data are collected at the state/territory level. Under the National Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse 2021–2030, a baseline analysis of specialist and community support services for victims and survivors of child sexual abuse is underway. Several activities will be undertaken as part of this work including an assessment by the Australian Institute of Health and welfare (AIHW) on the feasibility of developing a nationally consistent minimum data collection for the relevant support services. This project has the potential to build the foundations for improved availability of national specialist sexual violence services data in the longer term (AIHW 2022b).

The Australian Government launched the National Redress Scheme in October 2020 for people who have experienced institutional child sexual abuse. As of 31 March 2021, the majority of applications (60%) from the scheme resulted in people accepting an offer of counselling and psychological care (DSS 2021). Some of this counselling and psychological care may have been provided by specialist sexual violence services.

For information on data development work being undertaken in relation to specialist FDSV services collections, please see Key information gaps and development activities.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2023) Partner violence, ABS website, accessed 7 December 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2015), Screening for domestic violence during pregnancy: Options for future reporting in the National Perinatal Data Collection, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 June 2022.

AIHW (2019) Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 21 October 2022.

AIHW (2020a) Feedback from the AODTS Working Group, AIHW, unpublished.

AIHW (2020b) Inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence, Submission 24, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 3 May 2022.

AIHW (2021) Examination of hospital stays due to family and domestic violence 2010–11 to 2018–19, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 21 October 2022.

AIHW (2022a) Family, domestic and sexual violence data in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 21 October 2022.

AIHW (2022b) Family, domestic and sexual violence: National data landscape 2022, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 24 October 2022.

AIHW (2023a) AIHW analysis of the National Hospital Morbidity Database.

AIHW (2023b) National Perinatal Data Collection, 2021: Quality Statement, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 28 July 2023.

AIHW (2023c) Suicide and self-harm monitoring – Data sources, AIHW website, accessed 9 August 2023.

Crime Statistics Agency (CSA) (2022) Family violence data portal, Crime Statistics Agency, Victoria State Government, accessed 17 July 2023.

Cullen P, Walker N, Koleth M and Coates D (2022) Voices from the frontline: Qualitative perspectives of the workforce on transforming responses to domestic, family and sexual violence (Research report, 21/2022), ANROWS, accessed 5 June 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) Medicare Urgent Care Clinics, Australian Government, accessed 16 May 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2021) Strategic Success Measures July 2021, National Redress Scheme, Australian Government, accessed 17 November 2022.

DSS (2023) The Australian Government Response to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs report: Inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence, Australian Government, accessed 17 August 2023.

García-Moreno C, Hegarty K, d'Oliveira AF, Koziol-McLain J, Colombini M and Feder G (2015) The health-systems response to violence against women, The Lancet, 385(9977):1567–1579, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7.

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs (2021) Inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence, Parliament of Australia, accessed 5 June 2023.

KPMG (2016) The cost of violence against women and their children in Australia, DSS, accessed 5 June 2023.

NSW Health (2023) Domestic Violence Routine Screening Program, NSW Government, accessed 20 February 2023.

RACGP (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners) (2022) Abuse and violence – working with our patients in general practice, 5th edition, RACGP, accessed 17 January 2023.

Scott D, Heilbronn C, Coomber K, Curtis A, Moayeri F, Wilson J, Matthews S, Crossin R, Wilson A, Smith K, Miller P and Lubman D (2020a) The feasibility and utility of using coded ambulance records for a violence surveillance system: A novel pilot study, Australian Institute of Criminology, accessed 12 April 2023.

Scott D, Heilbronn C, Coomber K, Curtis A, Crossin R, Wilson A, Smith K, Miller P and Lubman D (2020b) The use of ambulance data to inform patterns and trends of alcohol and other drug misuse, self-harm and mental health in different types of violence, AIC, accessed 18 April 2023.

Townsend N, Loxton D, Egan N, Barnes I, Byrnes E and Forder P (2022) A life course approach to determining the prevalence and impact of sexual violence in Australia: findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, ANROWS, accessed 12 April 2023.

TCA (The Commonwealth of Australia) (2022) Women’s Budget Statement 2022–23, Department of the Treasury, Australian Government, accessed 12 April 2023.

UoM (The University of Melbourne) (2022) The HARMONY Study, Melbourne Medical School website, accessed 16 January 2023.

William J, Loong B, Hanna D, Parkinson B and Loxton D (2022) Lifetime health costs of intimate partner violence: A prospective longitudinal cohort study with linked data for out-of-hospital and pharmaceutical costs, Economic Modelling, 116:106013, doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2022.106013.

- Previous page How do people respond to FDSV?

- Next page Helplines and related support services