Summary

On this page:

- Introduction

- How common are chronic musculoskeletal conditions?

- Impact of chronic musculoskeletal conditions

- Treatment and management of chronic musculoskeletal conditions

- COVID-19 impact on chronic musculoskeletal conditions

- Comorbidities of chronic musculoskeletal conditions

- Where do I go for more information?

Conditions that affect the bones, muscles and joints and certain connective tissues are known as musculoskeletal conditions. These conditions include long-term (chronic) conditions such as back problems, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis or osteopenia, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and juvenile arthritis (see glossary).

Chronic musculoskeletal conditions in 2020–21

Data for 2020–21 are based on information self-reported by the participants of the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2020–21 National Health Survey (NHS).

Previous versions of the NHS have primarily been administered by trained ABS interviewers and were conducted face-to-face. The 2020–21 NHS was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. To maintain the safety of survey respondents and ABS Interviewers, the survey was collected via online, self-completed forms.

Non-response is usually reduced through Interviewer follow-up of households who have not responded. As this was not possible during lockdown periods, there were lower response rates than previous NHS cycles, which impacted sample representativeness for some sub-populations. Additionally, the impact of COVID-19 and lockdowns might also have had direct or indirect impacts on people’s usual behaviour over the 2020–21 period.

Due to these changes, comparisons with previous chronic musculoskeletal conditions data over time are not recommended.

On this page, comparisons over time (trends) only contain data from the NHS 2017–18 and prior collections.

How common are chronic musculoskeletal conditions?

An estimated 6.9 million or 27% of people in Australia were affected by chronic musculoskeletal conditions, based on self-reported data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2020–21 National Health Survey (NHS). Of these people:

- 3.9 million (16%) had back problems

- 3.1 million (12%) had arthritis

- 889,000 (3.6%) had osteoporosis or osteopenia (ABS 2022).

Prevalence by age and sex

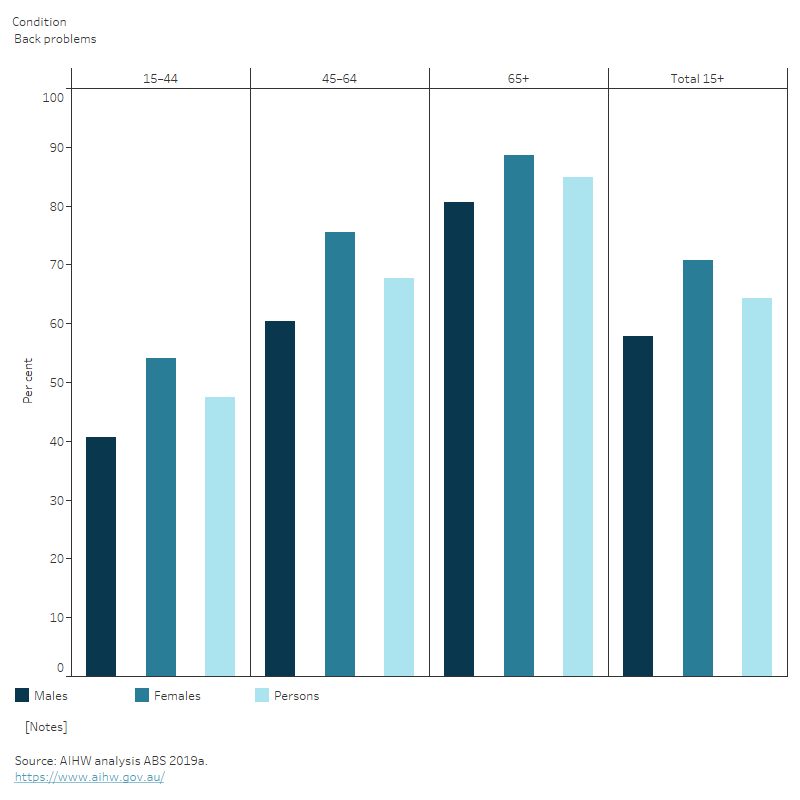

Females and older people were more likely to have chronic musculoskeletal conditions. According to the NHS, in 2017–18:

- 68% of people aged 75 and over had a musculoskeletal condition, compared with 13% of people aged under 45

- females, compared with males, were 1.2 times as likely to have any musculoskeletal condition, 4 times as likely to have osteoporosis, and 1.5 times as likely to have arthritis

- the prevalence of back problems was similar among males and females (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal condition, by sex and age, 2017–18

This figure shows that the prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions increased with age, from 14% for persons aged 0–44 to 68% for persons aged 75 and over.

Trends over time

Between 2007–08 and 2017–18 rates of chronic musculoskeletal conditions were relatively consistent (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal conditions, by sex, 2007–08 to 2017–18

This figure shows that 40% of females aged 45 and over had arthritis in 2017–18.

Variation between population groups

The prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions generally increased with increasing socioeconomic disadvantage, but was similar across remoteness areas, after adjusting for differences in age structures (Figure 3).

For more information see All arthritis, Back problems and Osteoporosis.

Figure 3: Prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal conditions in people aged 45 and over, by remoteness and socioeconomic area, 2017–18

This figure shows that 39% of persons living in the lowest socioeconomic area had arthritis in 2017–18.

Impact of chronic musculoskeletal conditions

Chronic musculoskeletal conditions are large contributors to illness, pain and disability in Australia. The 2018 Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers found that, of the people with disability in Australia, an estimated 13% had back problems and another 13% had arthritis as the main long-term health condition causing the disability (ABS 2019).

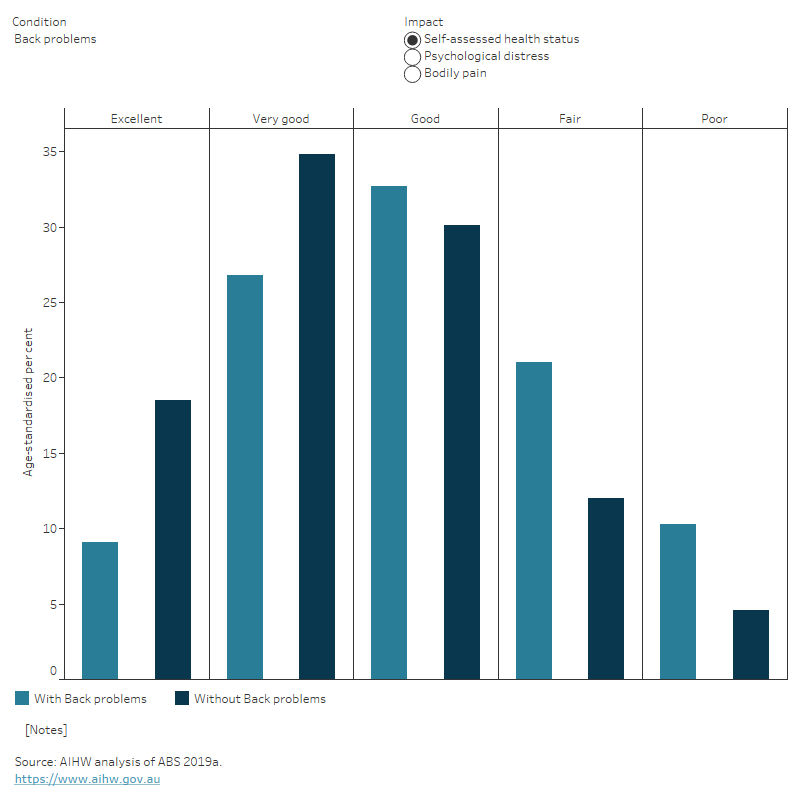

People with chronic musculoskeletal conditions reported higher rates of poor health, psychological distress and bodily pain compared with people without the condition, after adjusting for differences in age structures (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Impact of musculoskeletal conditions in people aged 45 and over, with and without the condition, age standardised, 2017–18

This figure shows that people with arthritis aged 45 and over were less likely to report having ‘excellent’ health compared with those without the condition.

Burden of disease

What is burden of disease?

Burden of disease is measured using the summary metric of disability-adjusted life years (DALY, also known as the total burden). One DALY is one year of healthy life lost to disease and injury. DALY caused by living in poor health (non-fatal burden) are the ‘years lived with disability’ (YLD). DALY caused by premature death (fatal burden) are the ‘years of life lost’ (YLL) and are measured against an ideal life expectancy. DALY allows the impact of premature deaths and living with health impacts from disease or injury to be compared and reported in a consistent manner (AIHW 2022a).

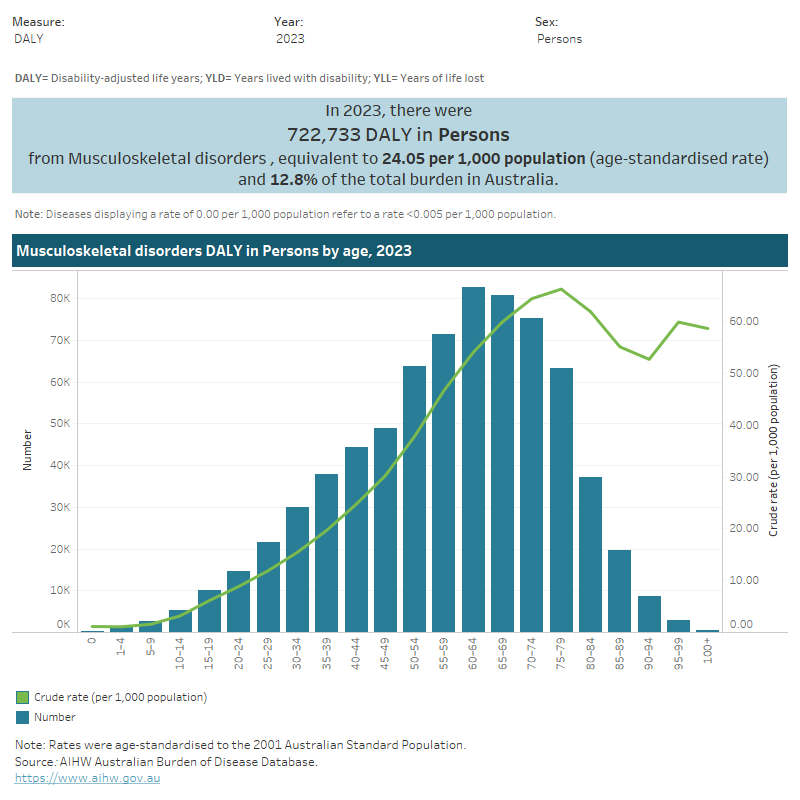

In 2023:

- the musculoskeletal conditions disease group accounted for 12.8% of total disease burden (DALY); 23.1% of non-fatal burden (YLD), and 0.8% of fatal burden (YLL). It was the second leading disease group contributing to non-fatal burden after cancer (AIHW 2023a)

- among all individual conditions, back problems were the leading cause of non-fatal burden (accounting for 7.9% of YLD)

- within the musculoskeletal conditions disease group, back problems accounted for 34% of burden (DALY), followed by other musculoskeletal conditions (30%), osteoarthritis (20%) and rheumatoid arthritis (16%).

Variation by age and sex

In 2023:

- the rate of burden from musculoskeletal conditions increased with age, peaking at ages 75–79 (66.3 DALY per 1,000 population)

- the age-standardised rate of total burden from musculoskeletal conditions was 20% higher among females compared with males (26.2 and 21.8 per 1,000 population, respectively) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Burden of disease due to musculoskeletal conditions by sex, age and year

This figure shows the fatal burden from musculoskeletal conditions was highest for people aged 75–79 (3.0 YLL per 1,000 population).

Trends over time

The age standardised rate of burden from musculoskeletal conditions was relatively stable between 2003 and 2023, averaging 24.2 DALY per 1,000 population across the 5 time points reported.

For more information, see the Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023.

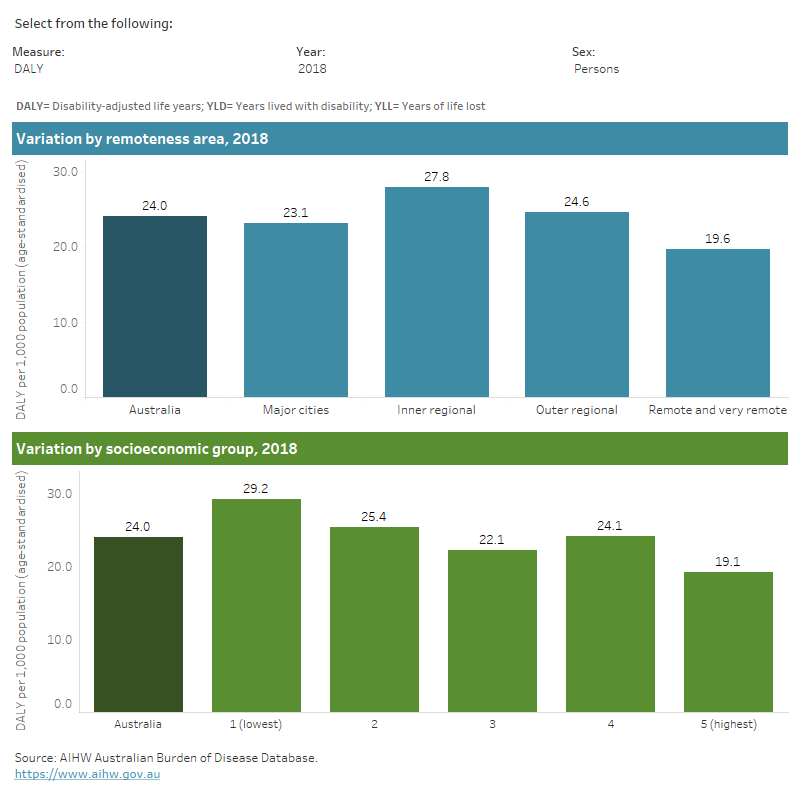

Variation between population groups

In 2018, the age standardised rate of total burden of musculoskeletal conditions:

- was highest for people living in Inner regional areas, and lowest for people living in Remote and very remote areas (27.8 and 19.6 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively)

- was 1.5 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage), compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest level of disadvantage) (29.2 and 19.1 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively) (AIHW 2021a) (Figure 6).

For more information, see the Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden.

Figure 6: Burden of disease due to musculoskeletal conditions for remoteness area and socioeconomic group and year

This figure shows that in 2018, the total burden of disease due to musculoskeletal conditions was highest for people living in Inner regional areas.

Modifiable risk factors contribute to burden

In 2018, 16% of the total burden (DALY) due to musculoskeletal conditions could be attributed to modifiable risk factors. These risk factors included:

- overweight and obesity, which contributed to 8.9% musculoskeletal burden, and 28% of the osteoarthritis burden

- occupational exposures and hazards, which contributed to 5.6% of musculoskeletal burden, and 17% of the back problems burden

- tobacco use, which contributed to 2% of the musculoskeletal burden (AIHW 2021a).

For definitions and information on the burden of disease associated with these conditions see Burden of disease.

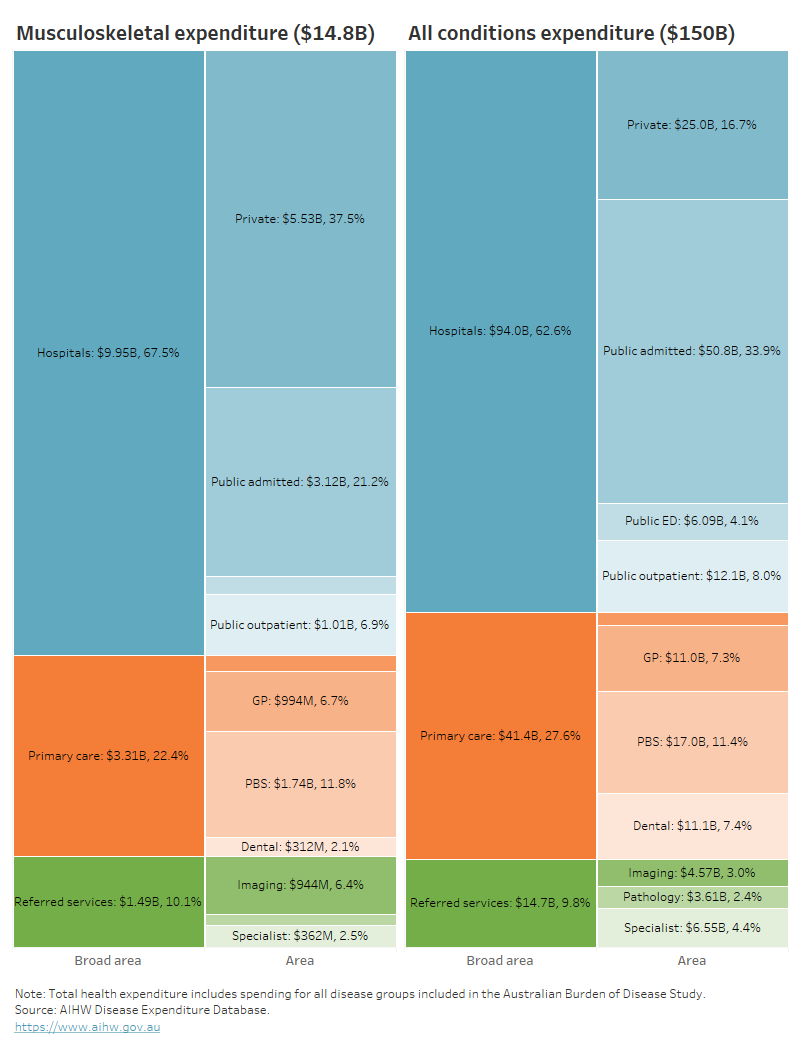

Health system expenditure

In 2020–21, an estimated $14.7 billion of expenditure in the Australian health system was for musculoskeletal conditions, representing the highest spending of all disease groups (9.8% of total health expenditure) (AIHW 2023b).

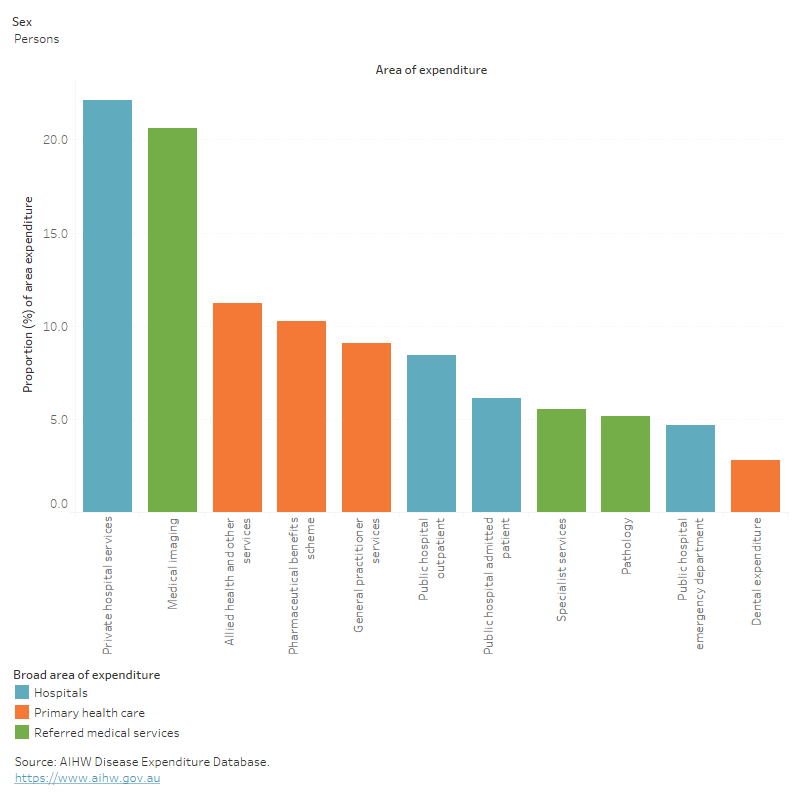

Where is the money spent?

In 2020–2021:

- hospital services represented 68% ($10 billion) of musculoskeletal expenditure, which was slightly higher than the hospital proportion for all disease groups (63%). The private hospital proportion of musculoskeletal expenditure was more than double the proportion for all disease groups (38% and 17%, respectively)

- primary care accounted for 22% ($3.3 billion) of musculoskeletal spending, which was slightly lower to the primary care proportion for all disease groups (28%).

- referred medical services represented 10% of musculoskeletal spending, which was similar to the referred services proportion for all disease groups. The medical imaging proportion of musculoskeletal expenditure was over double the proportion for all disease groups (6.4% and 3.0%, respectively).

Figure 7: Musculoskeletal condition expenditure attributed to each area of the health system, with comparison to all disease groups, 2020–21

This figure shows that the public admitted patients’ hospital proportion of musculoskeletal expenditure was 21% or $3.1 billion in 2020–21.

In 2020–21, musculoskeletal conditions accounted for:

- 22% ($5.5 billion) of all private hospital service expenditure – ranking first of all disease groups

- 21% ($943.7 million) of all medical imaging expenditure – ranking second of all disease groups (Figure 8)

Figure 8: Proportion of expenditure attributed to musculoskeletal conditions, for each area of the health system, 2020–21

This figure shows musculoskeletal conditions accounted for 11% of all allied health and other services expenditure in 2020–21.

Who is the money spent on?

The distribution of health system expenditure on musculoskeletal conditions by age and sex reflects the prevalence distribution, with more spending for older age groups and females. In 2020–21:

- 81% of musculoskeletal expenditure was for people aged 45 and over

- 21% more musculoskeletal expenditure was attributed to females than males ($7.9 billion and $6.5 billion, respectively) with a remaining $320.1 million (2.2%) unattributed to any sex.

For more information, see Health system spending on disease and injury in Australia, 2020-21.

In 2018–19, it was estimated that musculoskeletal conditions expenditure per case was similar for females and males (about $1,200 per case) (AIHW 2022b).

For more information, see Health system spending per case and for certain risk factors.

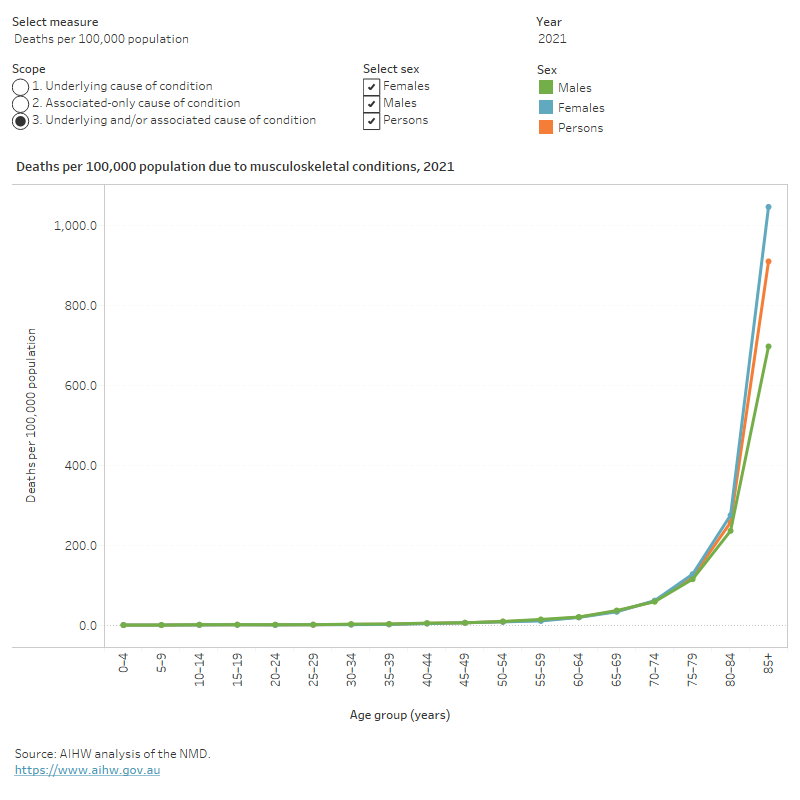

How many deaths were associated with musculoskeletal conditions?

In 2021, musculoskeletal conditions:

- were recorded as an underlying and/or associated cause for 9,277 deaths or 26.5 deaths per 100,000 population in Australia, representing 5.4% of all deaths

- were the underlying cause for 1,602 deaths (17% of musculoskeletal condition deaths) and an associated cause only, for 7,675 deaths (83% of musculoskeletal condition deaths).

Of the specific conditions analysed in this report, osteoporosis and osteoarthritis contributed the most substantially to any-cause musculoskeletal deaths (26% and 24% respectively), while rheumatoid arthritis contributed the most substantially to underlying-cause musculoskeletal deaths (14%).

Variation by age and sex

In 2021, musculoskeletal conditions mortality (as the underlying and/or associated cause) in comparison to all deaths, was relatively more concentrated among:

- older people (78% of musculoskeletal deaths were among people aged 75 and over, compared with 67% for total deaths)

- females (62% of musculoskeletal deaths were among females compared with 48% of total deaths) (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Age distribution for musculoskeletal condition mortality, by sex, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows that the death rates due to musculoskeletal conditions increased with age and was highest for people aged 85 and over.

Trends over time

Age standardised mortality rates for musculoskeletal conditions (as the underlying and/or associated cause) between 2011 and 2021:

- fluctuated in a range between 24 and 27 per 100,000 population

- were 1.2 to 1.3 times higher among females compared with males (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Trends over time for musculoskeletal condition mortality, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows deaths due to musculoskeletal conditions increased steadily from 2011 to 2017, decreased between 2017 and 2020 and increased again in 2021.

Variation between population groups

In 2021, age standardised mortality rates for musculoskeletal conditions (as the underlying and/or associated cause of death) were:

- 1.3 times as high for people living in Remote and very remote areas compared with people living in Major cities (32 and 25 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- 1.5 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the most disadvantage) compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the least disadvantage) (30 and 20 per 100,000 population, respectively).

Treatment and management of chronic musculoskeletal conditions

Primary care

Musculoskeletal conditions are usually managed by general practitioners and allied health professionals. Treatment can include physical therapy, medicines (for pain and inflammation), self-management (such as diet and exercise), education on self-management and living with the condition, and referral to specialist care where necessary (WHO 2019).

Until 2017, the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) survey was the most detailed source of data about general practice activity in Australia (Britt et al. 2016). According to this survey, an estimated 18% of general practice visits in 2015–16 were for management of musculoskeletal conditions (Britt et al. 2016).

It is worth noting that there is currently no nationally consistent primary health care data collection to monitor provision of care by GPs. See General practice, allied health and other primary care services.

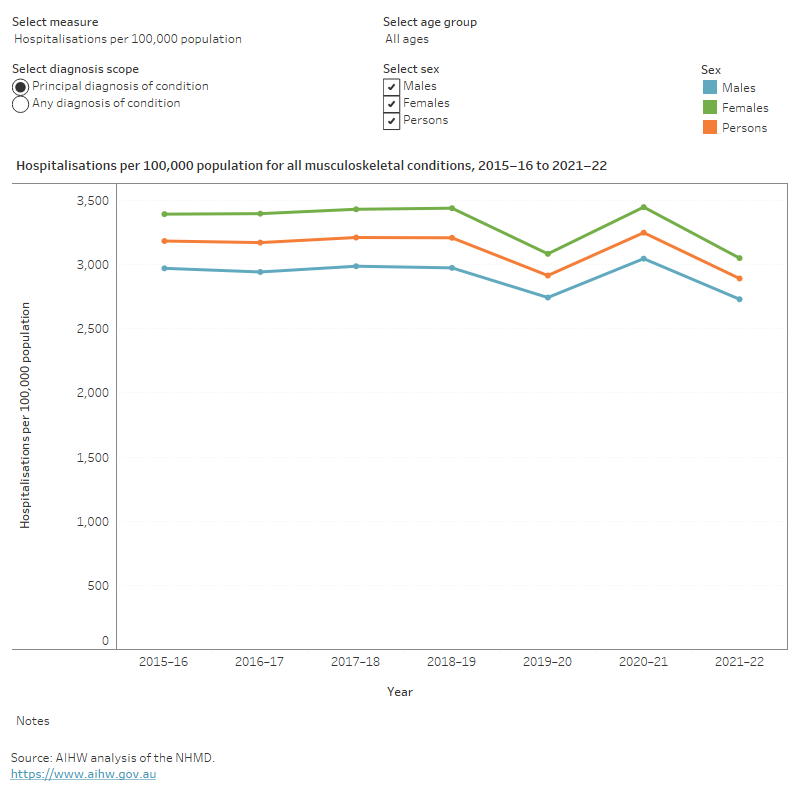

Hospital treatment

People with musculoskeletal conditions that are very severe, or who require specialised treatment or surgery, may be admitted to hospital.

Data from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD) show that in 2021–22, there were 1.1 million hospitalisations with a principal or additional diagnosis (any diagnosis) of musculoskeletal, together representing 9.5% of all hospitalisations.

The rest of this section discusses hospitalisations with a musculoskeletal principal diagnosis, unless otherwise stated. However, charts and tables also include statistics for any diagnosis of a musculoskeletal condition.

In 2021–22:

- there were 745,100 musculoskeletal condition hospitalisations, representing 6.4% of all hospitalisations in Australia, and 2,900 hospitalisations per 100,000 population

- musculoskeletal hospitalisations included: osteoarthritis (32%), back problems (24%), osteoporosis (1.4%), rheumatoid arthritis (1.3%), gout (0.9%), and other musculoskeletal conditions (40%)

- musculoskeletal conditions accounted for 2.4 million bed days, representing 7.6% of all bed days

- 49% of musculoskeletal condition hospitalisations were overnight stays, with an average length of 5.5 days (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Age distribution for musculoskeletal hospitalisations, by sex, 2015–16 to 2021–22

This figure shows that in 2021–22 hospitalisations for musculoskeletal conditions increased with age until 75–79 years, declining thereafter.

Variation by age and sex

In 2021–22, musculoskeletal conditions hospitalisation rates were:

- highest for people aged 75–79 years (10,200 per 100,000 population)

- 1.1 times as high for females compared with males (3,000 and 2,700 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 12).

Trends over time

From 2015–16 to 2021–22, for musculoskeletal hospitalisations:

- the rate was steady for the 4 years to 2018–19 (at about 3,200 hospitalisations per 100,000 population), and then fluctuated over the next 3 years, dipping to a low of about 2,900 hospitalisations per 100,000 population, in 2021–22

- the proportion and average length of overnight stays were relatively stable, averaging to 49% and 5.4 days, across the period (Figure 12).

It should be noted that the rate of hospitalisations over the past few years may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 12: Trends over time for musculoskeletal hospitalisations, 2015–16 to 2021–22

This figure shows that the hospitalisation rates for musculoskeletal conditions were consistently higher for females compared to males.

Data limitations

The prevention, management and treatment of musculoskeletal conditions beyond hospital settings cannot currently be examined in detail due to limitations in available data on:

- primary and allied health care at the national level

- use of over-the-counter medicines to manage pain and inflammation

- diagnosis information for prescription pharmaceuticals (which would allow a direct link between musculoskeletal conditions and use of subsidised medicines).

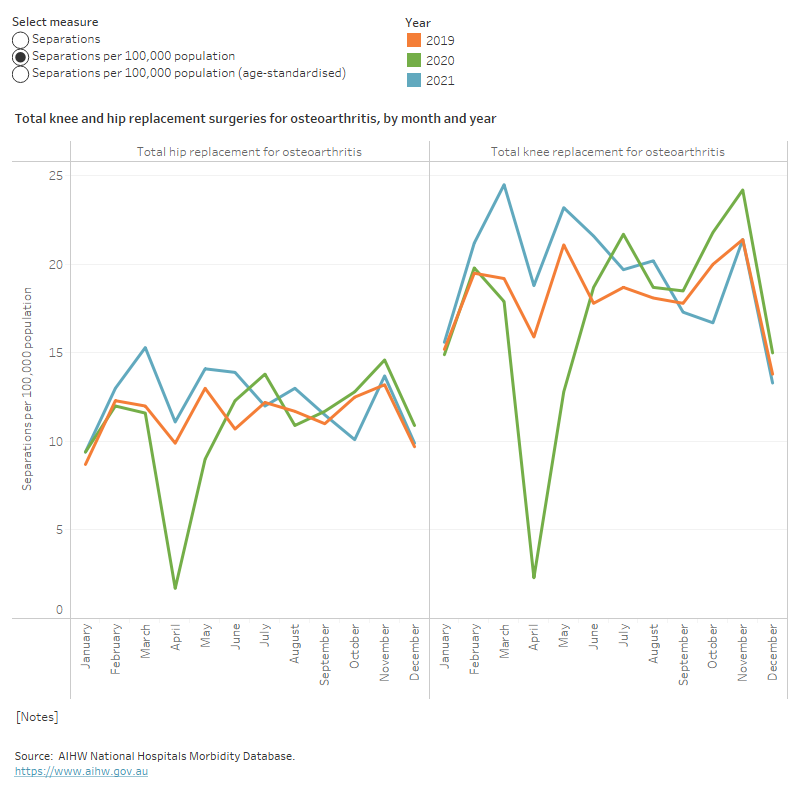

COVID-19 impact on chronic musculoskeletal conditions

The COVID-19 pandemic had substantial impacts on hospital activity generally. The range of social, economic, business and travel restrictions, including restrictions on, or suspension of, some hospital services, and associated measures in other healthcare services to support physical distancing in Australia resulted in an overall decrease in hospital activity between 2019–20 and 2020–21 (AIHW 2022c).

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, non-urgent elective surgery was suspended for one month, from late March to late April 2020. For more information on how the pandemic has affected the population’s health in the context of longer-term trends, see 'Chapter 2 Changes in the health of Australians during the COVID-19 period’ in Australia’s health 2022: data insights.

In 2019–20, the age standardised rate of total hip and knee replacement surgery where osteoarthritis was the principal diagnosis declined 8.6% and 11.4% respectively from 2018–19. This decrease was driven by the April–June 2020 quarter, which saw 31% and 37% fewer admissions for hip and knee replacements respectively, than April–June 2019 (Figure 13). In 2020–21, rates rebounded to exceed pre-pandemic levels, but decreased below pre-pandemic levels in 2021–22 (see Osteoarthritis).

Figure 13: Total hip and knee replacement surgeries, by month, 2019 to 2021

This figure shows that in 2021, there were between 2,000 and 4,000 separations per month for hip replacements where osteoarthritis was the principal diagnosis.

Waiting times for elective surgeries increased notably for 2020–21 admissions. In 2020–21, the median waiting times for total hip replacement surgery and total knee replacement surgery increased on 2019–20 by 49% and 38% respectively. This compares to an increase of 23% for all elective surgery (AIHW 2021b).

In 2020–21, the percentage of total hip replacements and total knee replacements with waiting times exceeding one year were 21% and 32% respectively. These represent 13 and 20 percentage point increases on 2019–20, which compare to a 4.8 percentage point increase for all elective surgeries (AIHW 2021b).

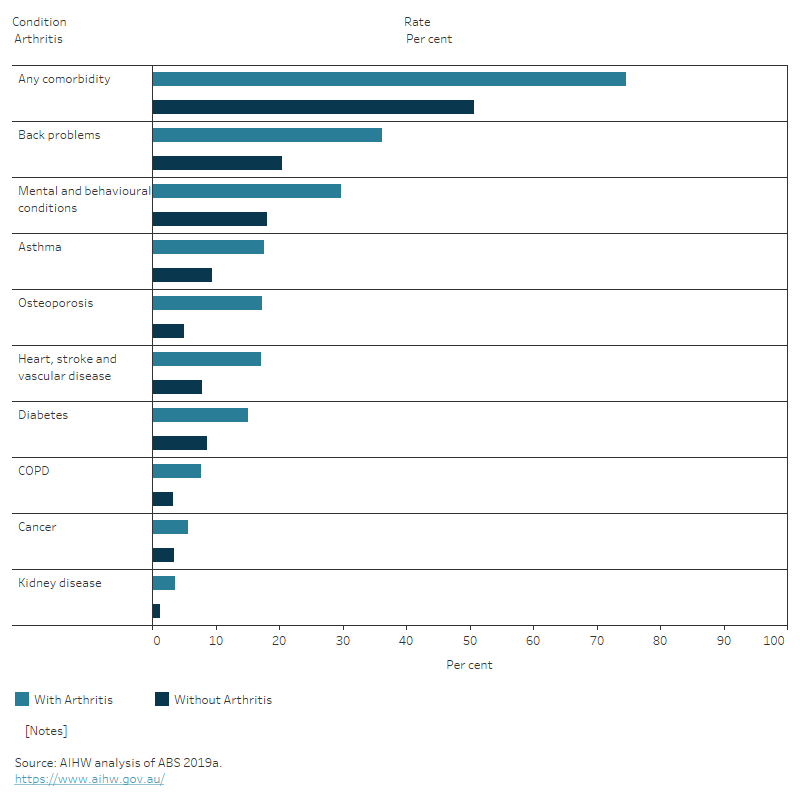

Comorbidities of chronic musculoskeletal conditions

People with musculoskeletal conditions often have other long-term conditions (comorbidities) (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Proportion of people with selected musculoskeletal conditions and 1 or more comorbidity, 2017–18

The number of comorbidities varies by age and sex. For example, the proportion of people with back problems who had at least one other chronic condition increased with age, from 47% (aged 1544) to 85% (aged 65 and over). Among those with back problems, the proportion of people with comorbidities was higher in females than males across all age groups (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Proportion of people with musculoskeletal conditions who have at least one other chronic condition in people aged 15 and over, by sex and age, 2017–18

This figure shows that with the prevalence of having at least one other chronic condition increased with age.

Musculoskeletal conditions often co-occur. In comparison to those without the condition, people aged 45 and over with:

- arthritis were 1.8 times as likely to also have back problems

- back problems were 1.6 times as likely to also have arthritis

- osteoporosis were 2.1 times as likely to also have arthritis.

Mental and behavioural conditions commonly co-occur with musculoskeletal conditions. Compared with people without musculoskeletal conditions, for people aged 45 and over with mental and behavioural conditions were:

- 1.9 times as likely in people with back problems

- 1.6 times as likely in people with arthritis

- 1.5 times as likely in people with osteoporosis (Figure 16).

Adjusting for differences in the age structure of the groups did not affect the pattern of these results.

Figure 16: Prevalence of other chronic conditions in people aged 45 and over, with and without musculoskeletal conditions, 2017–18

This figure shows that reporting of selected chronic conditions was more common in people aged 45 and over with musculoskeletal conditions than those without.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on the musculoskeletal conditions covered in this report, see:

- ABS National Health Survey – first results (2017–18)

- ABS Health Conditions Prevalence, 2020–21

- Australian Centre for Monitoring Health.

For more on this topic, visit Chronic musculoskeletal conditions.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2019) Disability, ageing, and carers, Australia: summary of findings, 2018, ABS website, accessed 18 February 2022.

ABS (2022) Health conditions prevalence, ABS website, accessed 21 March 2022.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden, AIHW website, accessed 10 March 2022.

AIHW (2021b) Elective Surgery, AIHW website, accessed 22 February 2022.

AIHW (2022a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2022, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 May 2023. doi:10.25816/e2v0-gp02.

AIHW (2022b) Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

AIHW (2022c) Admitted Patients, AIHW website, accessed 7 March 2022.

AIHW (2023a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

Britt H, Miller GC, Bayram C, Henderson J, Valenti L, Harrison C, Pan Y, Charles J, Pollack AJ, Chambers T, Gordon J and Wong C (2016) ‘A decade of Australian general practice activity 2006–07 to 2015–16’, General Practice Series, 43(1):1–155.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2019) Musculoskeletal conditions, WHO website, accessed 18 February 2022.