Overview of cancer in Australia, 2023

The following provides a brief summary of some notable trends in the latest cancer data. More comprehensive data is available throughout the Cancer data in Australia report for the cancers summarised as well as many other cancers.

Please note that when survival rates are discussed in the summary that these are relative survival rates. Age-standardised incidence and mortality rates are standardised to the 2023 Australian population. All cancers combined incidence data excludes basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. When discussing histology types, NOS is the abbreviation for ‘not otherwise specified’. The presence of NOS after a term generally indicates that a diagnosis is not as specific as it could theoretically be. For example, there are many kinds of adenocarcinoma but often the diagnosis is simply “adenocarcinoma”. This is referred to as “adenocarcinoma NOS”.

All cancers combined

The annual number of cancer cases diagnosed may surpass 200,000 by 2033

In 2000, there were around 88,000 cases of cancer diagnosed in Australia. By 2023, it is estimated there will be around 165,000 cases of cancer diagnosed in Australia. This 88% increase in the span of just over 20 years is mainly due to increases in population size and increasing numbers of people reaching older ages for which cancer rates are higher.

Had the cancer incidence rates from 2000 for the various age groups remained constant between 2000 and 2023 there would be around 154,000 cases of cancer diagnosed in Australia in 2023 – an increase of around 66,000 cases. This number is reflective of increases due to population size and the ageing population alone. The additional 11,000 cases to arrive at the estimated 165,000 cases is indicative of the increase due to increasing cancer rates. Overall, around 86% of the estimated increase of cancer incidence increase between 2000 and 2023 levels is attributable to population increase and the ageing population alone.

By 2033, with increasing population and estimated increasing rates of cancer, it is estimated there will be over 200,000 cases of cancer diagnosed in Australia.

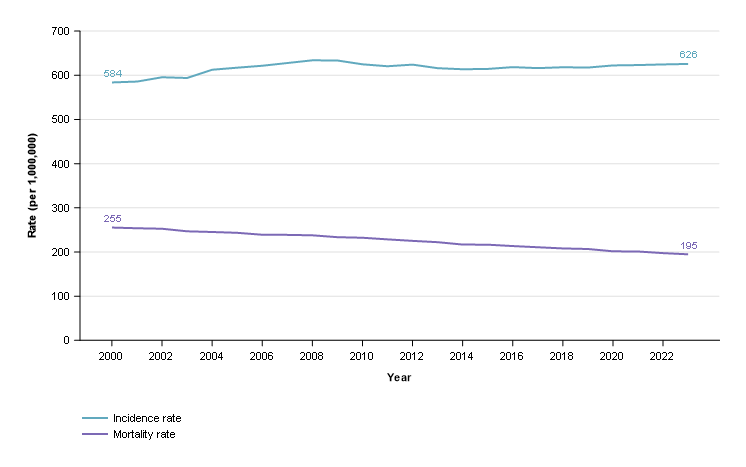

The age-adjusted cancer incidence rate increased from 584 cases per 100,000 people in 2000 to an estimated 626 cases per 100,000 people in 2023. Over the corresponding period, age-adjusted cancer mortality rates decreased from 255 deaths per 100,000 people to an estimated 195 deaths per 100,000 people (Figure 1). Increasing cancer survival rates increase the gap between incidence and mortality rates.

Figure 1: Age-standardised cancer incidence and mortality rates, persons, 2000–2023

Notes

- Rates are standardised to the 2023 Australian population.

- 2022 and 2023 are projections for mortality and 2020 to 2023 are projections for incidence.

Source: AIHW Australian Cancer Database 2019 and National Mortality Database

Cancer survival rates continue to increase

The 5-year survival for cancer in 1990–1994 was 53% and by 2015–2019, the rate had increased to 71%.

Even with decreasing mortality rates and increasing survival, the number of deaths from cancer has been increasing. In 2000, there were 36,000 deaths from cancer and by 2023 the number of deaths from cancer is estimated to have increased by 41% to 51,000 people. Had mortality rates from 2000 not improved and remained constant, there would have been around 67,000 deaths from cancer.

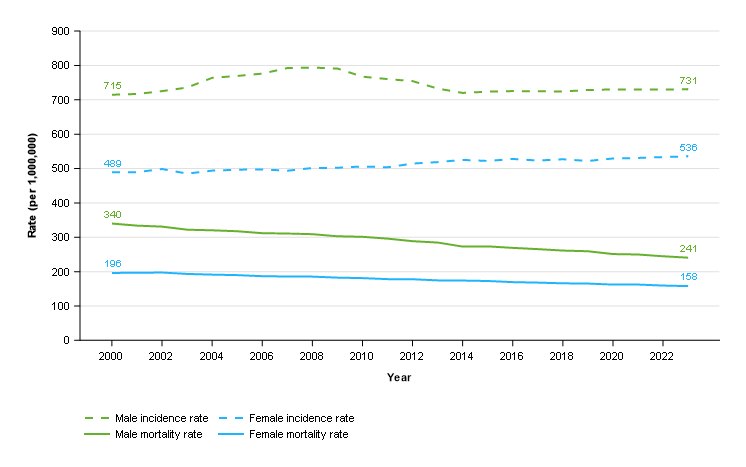

Males remain more likely to be diagnosed with cancer

Males continue to be more likely to be diagnosed with cancer although the difference in age-adjusted incidence rates between the sexes in 2023 is less than it was in 2000. In 2023, the age-adjusted cancer incidence rate for males is estimated to be 731 cases per 100,000 males and increased from 715 cases per 100,000 males in 2000. For the same period, the equivalent rate for females increased from 489 cases per 100,000 females to 536 cases per 100,000 females.

Age-adjusted cancer mortality rates for males and females have decreased between 2000 and 2023. The age-adjusted mortality rates for males decreased from 340 deaths per 100,000 males to an estimated 241 deaths per 100,000 males. The decrease in the age-adjusted mortality rate for females over the same period was 196 deaths per 100,000 females to 158 deaths per 100,000 females. Similar to cancer incidence, the difference in cancer mortality rates between the sexes remains high in 2023 but is less than it was in 2000 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Age-standardised cancer incidence and mortality rates, by sex, 2000–2023

Notes

- Rates are standardised to the 2023 Australian population.

- 2022 and 2023 are projections for mortality and 2020 to 2023 are projections for incidence.

- Prostate cancer incidence rates increased in the early 2000s before decreasing. The rate changes strongly influenced all cancers combined rates for males. More information about prostate cancer incidence is available in Cancer data commentary 9.

Source: AIHW Australian Cancer Database 2019 and National Mortality Database

Between 1990–1994 and 2015–2019, the 5-year survival rate for females increased from 58% to 72%. The corresponding survival rates for males improved from 49% to 69%. The greater improvements in survival for males and small increases in incidence rates leads to decreases in the gap between male and female mortality rates.

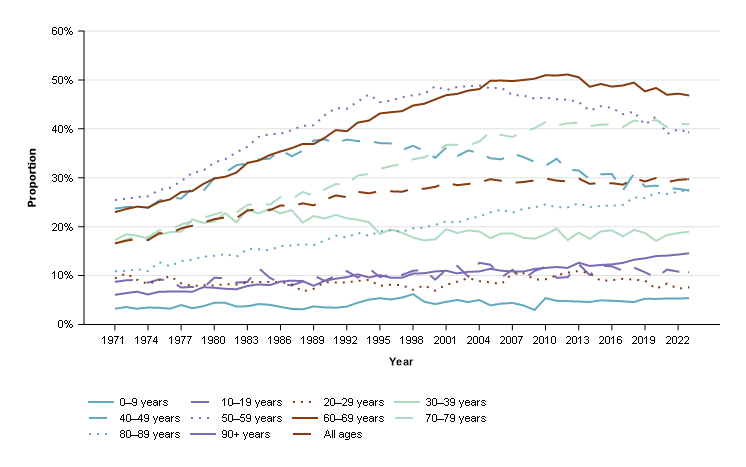

Cancer accounts for around 3 of every 10 deaths in Australia

In 2023, it is estimated that cancer will be responsible for around 3 of every 10 deaths in Australia. The percentage has increased gradually from 17% in 1971 but has been relatively stable between 28% and 30% from the turn of the century.

The rate of deaths from cancer varies considerably by age (Figure 3). In 2023, it is estimated to be responsible for around 47% of deaths in the population aged 60 to 69. The 0 to 9 age group has the smallest percentage of deaths from cancer and is estimated to be responsible for 5.4% of all death for the age group in 2023. In the 1970’s the proportion of deaths for this age group did not exceed 4%.

Figure 3: Percentage of deaths from cancer, by age group, 1971–2023

Note

- 2022 and 2023 are projections.

Source: National Mortality Database

Prostate cancer

In 2023, prostate cancer is estimated to be the most commonly diagnosed cancer for males and for Australia overall. With an estimated 25,500 cases diagnosed in 2023, prostate cancer is estimated to account for 28% of the cancers to be diagnosed in males for the year.

Since 2000, prostate cancer incidence rates have been more volatile than any other cancer (see Cancer commentary 9). Prostate cancer incidence projections have more uncertainty than other cancers but, if the most recent prostate cancer incidence rates were to remain the same, there would be around 30,900 cases of prostate cancer diagnosed in 2033.

In 2019, over 95% of prostate cancers diagnosed were adenocarcinomas. The 5-year survival rate for this type of prostate cancer in 2015–2019 was 98% and strongly influenced the overall prostate cancer 5-year survival rates of 96% for the period.

While prostate cancer survival rates are high, exceptions exist such as neuroendocrine neoplasms. Between 2015 and 2019, around 0.2% of prostate cancers diagnosed were neuroendocrine neoplasms. The 5-year survival rates for these prostate cancers in 2015–2019 was 12%.

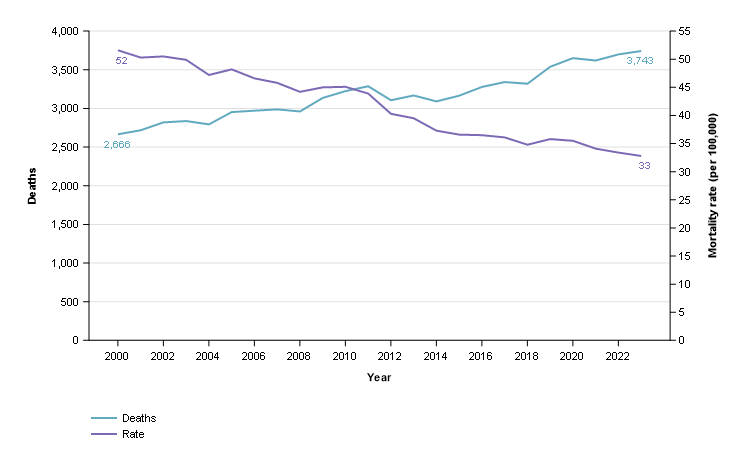

Prostate cancer mortality rates have been decreasing this century. Prostate cancer mortality rate reductions began in the early to mid 1990s, several years after the introduction of prostate specific antigen testing. In 1994, prostate cancer mortality rates were 62 deaths per 100,000 males. In 2023, it is estimated that prostate cancer mortality rates will be 33 deaths per 100,000 males, almost half of the rate from the peak mortality rate.

While the mortality rates have been decreasing, the number of deaths from prostate cancer continue to rise (Figure 4). In 2000, there were 2,666 deaths from prostate cancer and in 2023 it is estimated there will be 3,743. Population growth in combination with an ageing population exceeds reductions in age-adjusted mortality rates to result in increasing numbers of deaths from prostate cancer.

Figure 4: Prostate cancer deaths and age-standardised mortality rate, 2000–2023

Notes

- Rates are standardised to the 2023 Australian population.

- 2022 and 2023 are projections.

Source: National Mortality Database

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer for females in Australia.

It is estimated there will be around 20,500 breast cancer cases diagnosed in females in 2023. This is around 28% of the estimated cancers diagnosed in females. It is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australia for persons aged 20 to 39 and 60 to 79, and the most commonly diagnosed cancer for persons aged 40 to 59.

Breast cancer incidence has increased from 136 cases per 100,000 females in 2000 to an estimated 150 cases per 100,000 females in 2023. A large portion of the increase occurred around 2013 when breast screening was expanded to include women aged 70 to 74. Prior to this, breast cancer incidence rates were around 140 cases per 100,000 females in 2012.

Breast cancer 5-year survival improved from 78% in 1990–1994 to 92% in 2015–2019.

While survival rates for breast cancer overall are high, there is substantial variation in survival for different types of breast cancer. For females, carcinomas were the most common type of breast cancer accounting for 99% of all breast cancer cases in 2019. The main types of breast carcinoma were ductal carcinomas (84% of all breast cancer cases) followed by lobular carcinomas (13%). There are different types of ductal carcinomas which have varied survival rates. The most common type of ductal carcinoma, the infiltrating duct carcinoma (NOS) (73% of all breast cancers), had a 5-year survival of 93% in 2015–2019. For the same period, other less common ductal carcinomas had much lower 5-year survival rates (for example, inflammatory carcinomas (61%) and metaplastic carcinomas (74%)).

In 2023, it is estimated that nearly 3,300 females will die from breast cancer; in 2000, around 2,500 females died from breast cancer. Like many other cancers, the increasing number of deaths is attributable to increasing population size and the ageing population. Age-adjusted breast cancer mortality rates have been decreasing for females and were around 31 deaths per 100,000 females in 2000 compared to an estimated 23 deaths per 100,000 females in 2023.

Melanoma of the skin

Melanoma of the skin incidence rates have increased from 54 cases per 100,000 people in 2000 to an estimated 69 cases per 100,000 people in 2023. In 2023, it is estimated that 35% of melanoma of the skin cancer cases are diagnosed on the trunk of the body, 26% on the upper limbs (including shoulder), 18% on the lower limbs (including hip) and 7.6% on the scalp and neck.

The proportion of melanoma of the skin diagnosed by site varies by sex. For example, in 2023 it is estimated that 25% of melanoma of the skin cases are diagnosed on the lower limbs (including hip) for females while for males it is 13%. Conversely, the trunk accounts for 41% of the cases for males and 27% for females.

Melanoma of the skin incidence rates for females are estimated to be 56 cases per 100,000 females in 2023 while male rates are 85 cases per 100,000 males.

Melanoma of the skin incidence rates have been decreasing for people under 40 since the late-1990s. Incidence rates for people aged 40 to 49 ranged between 44 and 53 cases per 100,000 people since the mid-1990s. Rates for people aged 50 and over continue to rise.

The ‘Slip Slop Slap’ campaign was a very large skin cancer awareness and prevention campaign commencing from the early 1980s. In 2023, the population aged under 40 were born after or around the ‘Slip Slop Slap’ campaign and have spent their lives in an environment where skin cancer awareness has been greater. Skin cancer awareness and prevention advice continues today. While populations over 40 have increasing incidence rates, the rate increases are greater for the oldest populations who are likely to have spent more of their lives in times when there was less skin cancer awareness.

After many years of increasing, melanoma of the skin mortality age-adjusted rates peaked at 8 deaths per 100,000 people in 2013. In 2023, the estimated age-adjusted mortality rate is 5 deaths per 100,000 people. The reduction in mortality rates is accompanied by reductions in the number of deaths (1,625 deaths in 2013 and an estimated 1,300 in 2023).

Since 1995–1999, 5-year melanoma of the skin survival rates have been a little over 90%. The melanoma of the skin 5-year survival rate for 2015–2019 was 94% and is the highest rate recorded for melanoma of the skin.

Colorectal cancer

With around 15,400 cases estimated, colorectal cancer is estimated to be the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australia in 2023. At the beginning of the century, it was the most diagnosed cancer in Australia.

Since 2000, colorectal cancer incidence rates have decreased more than any other cancer. Age-standardised incidence rates peaked in 2001 at 86 cases per 100,000 people and are estimated to have decreased to an estimated age-standardised rate of 58 cases per 100,000 people in 2023.

Five-year survival for colorectal cancer increased from 55% in 1990–1994 to 71% in 2015–2019. Decreasing incidence combined with improvements in survival have led to reducing mortality rates. The age-standardised mortality rate for colorectal cancer decreased from 35 deaths per 100,000 people in 2000 to an estimated 20 deaths per 100,000 people in 2023.

Colorectal cancer is far more common in the older population than the young. In 2023, around 6% of colorectal cancers are estimated to be diagnosed in people aged under 40. In 2000, only around 2% of colorectal cancers were diagnosed in people aged under 40. The increasing proportion occurred because, while colorectal cancer is decreasing overall and for older populations, colorectal cancer incidence is increasing for the young.

Incidence rates for younger populations remain much lower than older but the trends are very different. Age groups under 40 years old have seen increases in incidence rates of colorectal cancer, particularly since around 2005. Incidence rates for 40–49 year olds increased from 22 cases per 100,000 people in 2005 to an estimated 29 cases in 2023. Over the same period, incidence rates decreased from 201 cases per 100,000 people to 145 cases per 100,000 people for the population aged 50 and over.

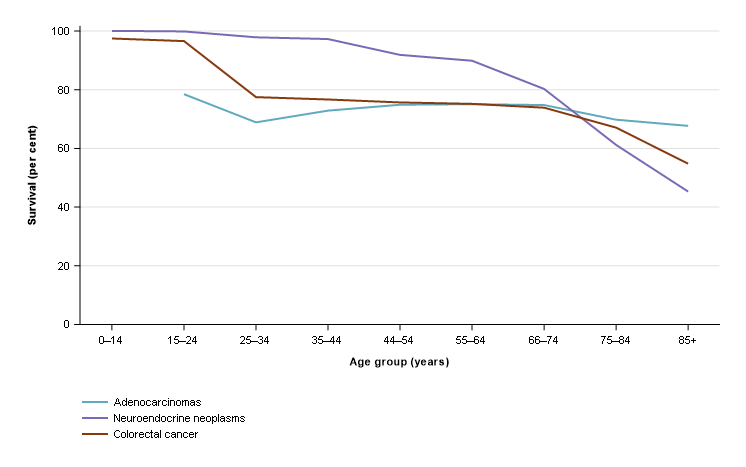

Some portion of the increasing rates for the younger population is attributable to neuroendocrine neoplasms but increases also occur for adenocarcinomas in the 20–39 age group. The increase for neuroendocrine neoplasms more generally may be explained by various factors such as increasing incidence of this malignancy, improvements in imaging technologies, increased use of endoscopy and colonoscopy, increased awareness in clinical practice and the introduction of the 2010 World Health Organisation classification for neuroendocrine tumours (Wyld D et al. 2019).

Cancer survival rates are higher for younger populations than older. In 2015–2019, survival was 98% for 0–19 year olds, between 70–80% for age groups 20–39, 40–59 and 60–79 years old, and then 61% for 80 years and older.

Colorectal cancer sites and types diagnosed differ by age. Some of these differences are discussed below but much more comprehensive information is available in the cancer by histology and cancer by subsite data visualisations and spreadsheets.

Colorectal cancer can originate in the broad areas of the colon, rectum or the rectosigmoid junction (which is the limit separating the sigmoid colon and the rectum). In 2023, it is estimated that most cases of colorectal cancer will be in the colon (70% of all colorectal cancer cases), followed by the rectum (23%) and lastly the rectosigmoid junction (7%). The appendix, which is part of the colon, is not a common site of colorectal cancer in the overall population (estimated 5% of cases in 2023). However, the majority of colorectal cancer cases in the youngest age groups are located in the appendix (estimated 100% of cases in 0–14 year olds and an estimated 88% of cases in 15–24 year olds in 2023).

The majority of colorectal cancers diagnosed were carcinomas (96% of all colorectal cancers in 2019). In the general population, the most common type of colorectal carcinoma diagnosed was adenocarcinomas (88%) followed by neuroendocrine neoplasms (5%). However, neuroendocrine neoplasms were very common in younger age groups accounting for 100% and 89% of colorectal cancer cases in 0–14 and 15–24 year olds respectively.

Colorectal survival outcomes differ by age and type. Figure 5 provides a small selection of these for 2015–2019. Adenocarcinomas had a 5-year survival of 73% in 2015–2019 while neuroendocrine neoplasms had 89% survival. However, the difference in survival for neuroendocrine neoplasms is partly due to greater proportions of cases of this cancer being in younger age groups, who tend to have higher survival than older age groups. More extensive statistics are available in the cancer by histology data visualisation and Excel data.

Figure 5: Colorectal cancer 5-year relative survival by specified histologies, by age group, 2015–2019

Source: AIHW Australian Cancer Database 2019

Lung cancer

With around 14,800 cases estimated, lung cancer is estimated to be the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australia in 2023. Of the 5 most common cancers in Australia, its survival rates are the lowest (5-year survival of 24% in 2015–2019 for lung cancer with colorectal cancer survival the next lowest at 71%).

While lung cancer is a low survival cancer, 5-year survival rates have improved over time. Survival increased from 10% in 1990–1994 to 20% in 2015–2019 for males and from 12% to 29% for females. Survival differs by age with 5-year survival for 20–24-year-olds at 94%, 77% for 25–29, 56% for 30–34, between 25% and 32% for age groups between 40 and 74, and only 7% for those aged 85 and over in 2015–2019.

Lung cancer age-standardised incidence rates have been fairly stable at 58 cases per 100,000 people in 2000 and an estimated 56 cases in 2023. National rates are however comprised of very different trends for males and females. Males have seen strong and enduring decreases from 85 cases per 100,000 males in 2000 to an estimated 62 cases per 100,000 males in 2023. In contrast, females have seen an increase from 36 cases per 100,000 females in 2000 to an estimated 51 cases per 100,000 females in 2023.

The increasing incidence rates of this low survival cancer have seen lung cancer account for increasing proportions of cancer deaths for females. In 2000, lung cancer accounted for around 15% of cancer deaths in females and is estimated to be 17% in 2023. Conversely, lung cancer represented 22% of all cancer deaths for males in 2000 and this has reduced to 17% in 2023.

In 2023, it is estimated that around 8,700 people will die of lung cancer in Australia. This is the most common cause of cancer-related death. Age-standardised mortality rates for males have decreased substantially from 74 deaths per 100,000 males in 2000 to an estimated 40 deaths per 100,000 males in 2023. Female lung cancer mortality rates remain lower than males, but in contrast to males have increased from 30 deaths per 100,000 females in 2000 to a peak of 32 deaths in 2010 before decreasing to an estimated 27 deaths per 100,000 females in 2023.

Blood cancers

All blood cancers combined is the aggregate of many different types of blood cancer. While useful for detailing the overall number of cases and general survival of these cancers in Australia, different types of blood cancer often have different incidence and mortality trends and survival rates.

In 2023, it is estimated that around 19,500 people will be diagnosed with a blood cancer (59% in males). The most common type of blood cancer in 2023 is estimated to be non-Hodgkin lymphoma followed by multiple myeloma and then chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

Blood cancers accounted for an estimated 12% of all cancer cases in 2023. However, blood cancers were particularly common in the 0–19 year old age group accounting for an estimated 38% of all cancer cases. While not a common cancer in the general population, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia was the most common cancer diagnosed in 0–19 year olds (estimated 17% in 2023).

Age-standardised incidence rates for blood cancer increased from 66 cases per 100,000 in 2003 to an estimated 74 cases in 2023. Males have had consistently higher rates of all blood cancers combined than females (estimated 92 compared to 58 cases per 100,000 males and females respectively in 2023).

Five-year survival increased slightly from 66% in 2010–2014 to 69% in 2015–2019. In 2015–2019, survival was over 90% for age groups 0–19 and 20–39, and then decreased with age from 84% in 40–59 year olds to 69% in 60–79 year olds to 42% for those aged 80 years older. There is substantial variation in survival between different types of blood cancer. Blood cancers with comparatively higher 5-year survival in 2015–2019 were Hodgkin lymphoma (89%), and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (86%). Lower survival blood cancers included acute myeloid leukaemia (27%) and myelodysplastic syndromes (39%).

Age-standardised blood cancer mortality decreased from 30 deaths per 100,000 in 2000 to an estimated 23 deaths in 2023. This decrease was seen in both males and females although males had consistently higher mortality rates.

The Cancer data in Australia report now contains a considerable amount of new data on blood cancers. More specifically, it provides a greater depth of incidence and survival rates. For example, Hodgkin lymphoma incidence and survival statistics are accompanied by statistics on types of Hodgkin lymphoma such as nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin, classic Hodgkin lymphoma and the subtypes nodular sclerosis classic Hodgkin lymphoma, lymphocyte-rich classic Hodgkin lymphoma, mixed cellularity classic Hodgkin lymphoma and lymphocyte-depleted classic Hodgkin lymphoma. The Blood cancers by types and subtypes data visualisations provide the new and more detailed blood cancer statistics.

Gynaecological cancers

Gynaecological cancers include cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, placental cancer, uterine cancer, vaginal cancer, vulvar cancer, and cancer of other female genital organs. Gynaecological cancer is estimated to account for around 9% of cancers diagnosed in females in 2023 and around 10% of female deaths from cancer.

In the following paragraphs, ovarian cancer and serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube are discussed rather than ovarian cancer. This is because the time series for this cancer appears to better reflect ovarian cancer as it is more traditionally understood while ovarian cancer trends are complicated by the changed understanding of where many serous carcinomas originate (see Cancer data commentary 5 for more information).

Gynaecological cancer incidence rates ranged between 49 and 53 cases per 100,000 females between 1982 and 1994 before decreasing to a low of 45 cases per 100,000 females in 2003. Decreases in cervical cancer incidence drove the reduction where rates decreased from 14 to 7.7 cases per 100,000 females between 1994 and 2003. The National Cervical Cancer Screening program was introduced in 1991 and led to falls in cervical cancer incidence and mortality due to the program’s ability to detect pre-cancerous abnormalities that may, if left, progress to cancer.

Since 2003, gynaecological cancer incidence has gradually increased to an estimated 49 cases per 100,000 females in 2023. Uterine cancer has largely influenced this change and increased from 20 to an estimated 24 cases per 100,000 females between 2003 and 2023. Uterine cancer incidence had been increasing before this time and has been steadily and gradually increasing since 1989 (16 cases per 100,000 females).

Five-year survival for gynaecological cancers has improved from 64% in 1990–1994 to 71% in 2015–2019. There is substantial variation in survival between different types of gynaecological cancers. The gynaecological cancers with the highest survival in 2015–2019 were placental (85%), and uterine (83%). Lower survival gynaecological cancers include ovarian cancer and serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube (49%) and vaginal cancer (55%). Ovarian cancer and serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube 5-year survival rates have been improving over time, increasing from 39% in 1990–1994. Vaginal cancer 5-year survival rates have also improved from the 2005–2009 survival rate of 43%.

The mortality rate for gynaecological cancer has declined from 18 deaths per 100,000 females in 2000 to an estimated 16 deaths in 2023. Mortality rates for cervical cancer decreased from 3.2 deaths per 100,000 females in 2000 to an estimated 1.6 deaths in 2023. Mortality for uterine cancer increased from 3.3 deaths per 100,000 females in 2000 to an estimated 4.8 deaths in 2023.

In 2023, ovarian cancer and serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube are estimated to account for around 26% of the gynaecological cancers diagnosed. With survival lower than other gynaecological cancers, and an estimated 1,050 deaths in 2023, ovarian cancer and serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube are estimated to account for 48% of the 2,180 deaths from gynaecological cancer in 2023.

Brain cancer

Brain cancer incidence rates from 2000 to 2023 ranged between 7 and 9 cases per 100,000 people. Males had higher incidence rates than females throughout this period. In 2023, the incidence rate for males is estimated to be 9.4 cases per 100,000 males and the rate for females is estimated to be 5.4 cases per 100,000 females.

Survival vastly differs by age; in 2015–2019, 5-year survival for brain cancer was 64% for 0–19 year olds, 67% for 20–39 year olds, 27% for 40–59 year olds, 8.5% for 60–79 year olds and 1.7% for 80 years and over.

Overall, brain cancer survival has improved from 19% in 1990–1994 to 23% in 2015–2019. Brain cancer survival rates over time are often impacted by changes in the age composition of those diagnosed with brain cancer. In particular, greater proportions of older people are diagnosed and older people have lower survival rates. When adjusted for age, brain cancer 5-year survival has more than doubled from 11% in 1990–1994 to 23% in 2015–2019.

The mortality rate for brain cancer ranged from 6 to 7 deaths per 100,000 people between 2000 and 2023.

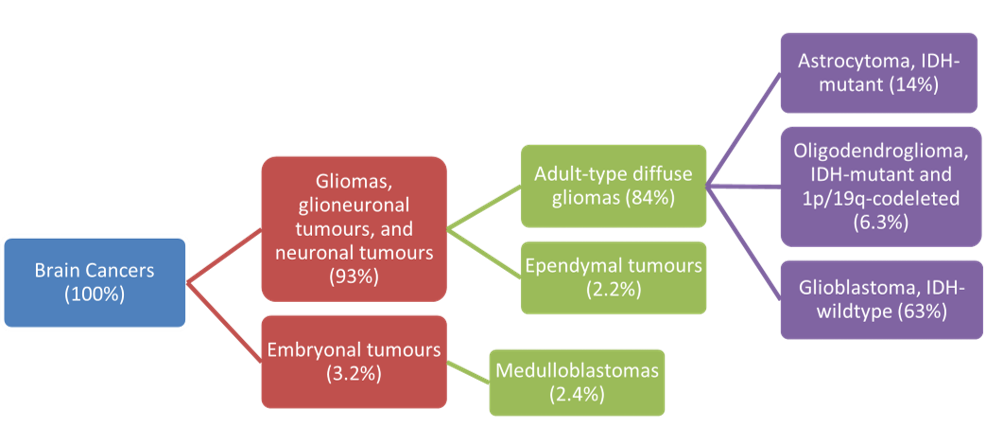

The most common types of brain cancer were gliomas, glioneuronal tumours and neuronal tumours, which accounted for 93% of brain cancers diagnosed in 2019. Embryonal tumours only accounted for 3% of brain cancers in the general population but 39% of brain cancers in 0–19 year olds. Survival varies considerably for different types of brain cancer. Glioblastomas, IDH-wildtype accounted for 63% of all brain cancers in 2019 and had a 5-year relative survival of only 5.7% in 2015–2019.Oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q-codeleted accounted for 6% of brain cancer cases and had 84% survival.

Figure 6: Brain cancer incidence, selected types, persons, 2019

Source: AIHW Australian Cancer Database 2019

Thyroid cancer

Thyroid cancer is a common cancer, particularly in females. In 2023, it is estimated that around 4,100 cases will be diagnosed, approximately 70% of which will be in females.

The incidence of thyroid cancer increased from 8.5 cases per 100,000 females in 2000 to an estimated 21 cases in 2023. While lower, the incidence rates for males have also increased from 3.3 cases to an estimated 9.6 cases per 100,000 males over the same period. The increase in thyroid cancer may be due to an increase in medical surveillance and the introduction of new diagnostic techniques such as neck ultrasonography (Vaccarella et al. 2016).

While thyroid cancer is common, it is a high survival cancer resulting in relatively few deaths. Five-year survival is higher for females than males (98% and 93% in 2015–2019 respectively).

Despite an increase in the incidence rate, the mortality rate for thyroid cancer has been broadly stable since 2000, between 0.5 and 0.7 cases per 100,000 people. However, males are overrepresented in deaths from thyroid cancer. While it is estimated that only around 30% of thyroid cancer cases in 2023 will be in males, almost half the deaths are estimated to be males (71 of the 146 deaths in 2023).

Rare cancers

Rare Cancers Australia defines a cancer to be ‘rare’ if it has an incidence rate of less than 6 cases per 100,000 people per year. If the incidence rate is greater than or equal to 6 cases per 100,000 people per year but less than 12 cases per 100,000 people per year, the cancer is ‘less common’. ‘Common’ cancers are defined as those with an incidence rate of 12 or more cases per 100,000 people per year.

Cancers that changed from rare to less common between 2000 and 2019 were chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, liver cancer, multiple myeloma and oesophageal cancer. Cancers that changed from less common to common were kidney cancer and pancreatic cancer. Thyroid cancer was the only cancer to go from rare to common between 2000 and 2019. Cancer of unknown primary site was the only cancer to change from common to less common between 2000 and 2019.

Rare cancers are individually rare, but collectively account for 13% of cases diagnosed in 2019. Less common cancers accounted for around 14% of cancer cases in 2019 and common cancers for around 73% of cases. While rare and less common cancers are estimated to collectively account for 27% of cases, they are estimated to account for 38% of all cancer deaths in 2019 (Table 1).

| Type | Number of cases | Percent of all cancer cases | Number of deaths | Percent of all deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rare cancers | 18,645 | 13% | 6,738 | 14% |

| Less common cancers | 21,384 | 14% | 10,908 | 23% |

| Common cancers | 107,562 | 73% | 29,288 | 62% |

Notes:

- Rare cancers are those with incidence rates of less than 6 cases per 100,000 people. Less common cancers are those with incidence rates of at least 6 and less than 12 cases per 100,000 people. Common cancers are those with incidence rates of 12 or more cases per 100,000 people (with rarity based on estimated rates from 2019).

- Individual cancers were grouped based on rarity and the numbers of new cases were summed accordingly.

- The sum of cancers by rarity for mortality will not equal all cancers combined estimated as stated from either the NMD or ACD as the individual cancers in the cancer rarity estimates were sourced from whichever of the NMD or ACD are recommended for use.

- Non-melanoma skin cancer rarity classification is derived from cancer incidence rates that exclude basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. For consistency, non-melanoma skin cancer mortality also excludes basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin.

- The sum of cancers by rarity will not equal all cancers combined incidence totals from the ACD as the small number of bone cancers outside of C40-C41 ICD-10 coding are coded to bone cancer as well as the relevant ICD-10 site.

- Cancer incidence and mortality counts and proportions may change depending on the cancers included within analysis.

Source: AIHW Australian Cancer Database 2019 and National Mortality Database

Survival differs by cancer rarity, in 2015–2019, collectively rare cancers had 62% 5-year relative survival, less common cancers had 45% and common cancers had 77% (Table 2). Since the 1990’s, 5-year relative survival for the common cancer group has improved more than the rare or less common cancer groups.

| Type | Survival | Survival 2015–2019 |

|---|---|---|

| Rare cancers | 52% | 62% |

| Less common cancers | 35% | 45% |

| Common cancers | 58% | 77% |

Notes:

- Rare cancers are those with incidence rates of less than 6 cases per 100,000 people. Less common cancers are those with incidence rates of at least 6 and less than 12 cases per 100,000 people. Common cancers are those with incidence rates of 12 or more cases per 100,000 people (with rarity based on estimated rates from 2023).

- Individual cancers were grouped based on rarity and the numbers of new cases were summed accordingly.

- Non-melanoma skin cancer rarity classification is derived from cancer incidence rates that exclude basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin.

Source: AIHW Australian Cancer Database 2019