Policy framework for reducing homelessness and service response

On this page

People experiencing homelessness and at risk of homelessness are among Australia’s most socially and economically disadvantaged. Governments across Australia fund a range of services to provide support to those who are experiencing homelessness or are facing housing insecurity. These services are delivered by various government and non-government organisations including agencies specialising in delivering support to specific target groups (such as young people or people experiencing family and domestic violence), as well as those that provide more generic services to those experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

Many Australians experience events in their lifetime that may place them at risk of, or result in, homelessness. Access to affordable housing is a key issue for all Australians, particularly for those on low incomes. A lack of affordable housing puts households at an increased risk of experiencing housing stress and can affect their health, education, employment and place them at risk of homelessness (AIHW 2022, Chung et al. 2020, Desmond and Gerhenson 2016, Guran et al. 2021, Rowley and Ong 2012).

During 2021–22, the effects of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continued to exacerbate housing affordability in Australia. Lockdowns of varying length in a number of states and territories continued to cause many households to experience income losses, resulting in increased housing stress, while the ongoing housing price boom has put out of reach for many Australians the chance to own their own home, and further driven up the rental cost to beyond affordable for many renters (Pawson 2021) (see below for more COVID-19-related housing impacts). It is estimated that around 1 million low-income households experience housing affordability issues due to rental stress – defined as paying more than 30% of their gross weekly income on housing costs (ABS 2022).

On Census night in 2016, 116,427 Australians were homeless, up from 102,439 people in 2011. This equates to a 4.6% increase in the population adjusted rate of homeless persons over 5 years, from 47.6 per 10,000 population in 2011 to 49.8 in 2016. Census homeless estimates include people in supported accommodation for the homeless, people in short-term or emergency accommodation, those ‘sleeping rough’ and people living in severely crowded dwellings – defined as those households that require 4 or more extra bedrooms to accommodate residents. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) acknowledges that the circumstance of homelessness may mean that some people are not captured at all in datasets, nor will all those experiencing homelessness be captured in datasets of those accessing particular homelessness services. In addition, certain groups of people (including Indigenous Australian populations, rough sleepers and those in supported accommodation) are more likely to be undercounted on Census night. Hence, homelessness data collected in the Census is an estimation, and susceptible to under/overestimation and under enumeration (ABS 2018).

The National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA)

In the 2017–18 Budget, the Australian Government announced the establishment of a new National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NHHA), which came into effect on 1 July 2018. This agreement reformed previous funding agreements with states and territories (the National Affordable Housing Agreement (NAHA) supported by the National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness (NPAH)). The NHHA provides more than $1.6 billion in Commonwealth funding to the states and territories a year, including dedicated funding of $124.7 million over two years from 2021–22 to support workers in the housing and homelessness sector (The Commonwealth of Australia 2021). In addition to funding provided through the NHHA, in 2022–23 the Australian Government committed to provide funding of $313.7 million to support state affordable housing services, including HomeBuilder and Remote housing programs as part of the National Partnership payments (The Commonwealth of Australia 2022).

Under the Agreement, funding for homelessness services will be ongoing and indexed for the first time to provide certainty to front line services assisting Australians who are experiencing homelessness or who are at risk of homelessness (CFFR 2018).

The objective of the NHHA

The objective of the NHHA is to contribute to improving access to affordable, safe and sustainable housing across the housing spectrum from crisis housing to home ownership (including to prevent and address homelessness), and to support social and economic participation.

The key outcomes this agreement will contribute to include:

- a well-functioning social housing system that operates efficiently, sustainably and is effective in assisting low-income households and priority homeless cohorts to manage their needs

- affordable housing options for people on low-to-moderate incomes

- an effective homelessness system, which responds to and supports people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness to achieve and maintain housing, and addresses the incidence and prevalence of homelessness

- improved housing outcomes for Indigenous Australians

- a well-functioning housing market that responds to local conditions

- improved transparency and accountability in respect of housing and homelessness strategies, spending and outcomes.

Several homelessness priority cohorts have been specifically identified in the agreement and must be addressed in each state and territory’s homelessness strategy:

- women and children affected by family and domestic violence

- children and young people

- Indigenous Australians

- people experiencing repeat homelessness

- people exiting institutions and care into homelessness

- older people.

In addition, several homelessness priority policy reform areas have been identified:

- achieving better outcomes for people

- early intervention and prevention

- commitment to service program and design.

Emerging housing policies

As part of the October 2022–23 Budget, the Australian Government committed to the implementation of a number of housing reforms which aim to address housing affordability and homelessness. These commitments include:

- A new national Housing Accord which aims to build “one million new, well-located homes to be delivered over 5 years from mid‑2024 as capacity constraints are expected to ease”

- The $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund that will build 30,000 social and affordable housing properties over 5 years

- Help to Buy program giving eligible home buyers access to an equity contribution from the Government

- The Regional First Home Buyer Support Scheme for 10,000 eligible first home buyers guaranteeing up to 15 per cent of the purchase price

- Establishing a National Housing Supply and Affordability Council to independently advise the Australian Government on housing policy

- Developing a new National Housing and Homelessness Plan.

The Government has committed to providing $15.2 million to establish the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council, which “will be responsible for delivering advice on options to improve housing supply and affordability, reporting on key issues in housing policy, and promoting the regular collection and publication of data on housing supply, demand and affordability” (Australian Government 2022).

Specialist homelessness services

A specialist homelessness service is an organisation that receives government funding to deliver accommodation related and/or personal services to people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. Under the NHHA, these agencies are required to participate in the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC). Other organisations not directly funded by governments also provide a wide range of support services to people in need; these organisations are not required to provide data to the SHSC. Also, NHHA funded agencies may provide support beyond the NHHA directly funded support packages; this support is also excluded from the SHSC.

SHS agencies vary in size and in the types of assistance they provide. Across Australia, agencies provide services aimed at prevention and early intervention, as well as crisis and post crisis assistance to support people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. For example, some agencies focus specifically on assisting people experiencing homelessness, while others deliver a broader range of services, including youth services, family and domestic violence services and housing support services to those at risk of becoming homeless. The service types an agency provides range from basic, short-term interventions such as advice and information, meals and shower or laundry facilities through to more specialised, time intensive services such as financial advice and counselling and professional legal services (see Glossary for a complete list of service types).

The Specialist Homelessness Services Collection

Around 1.5 million clients have been supported by Specialist Homelessness Services since the collection began on 1 July 2011.

The SHSC comprises data from homelessness agencies funded under the NHHA). State and territory departments identify NHHA (and the previous NAHA and NPAH) funded agencies required to participate in the SHSC. These agencies vary widely in terms of the services they provide and the service delivery frameworks they use. The operational frameworks may be determined by the state or territory funding department or developed as a response to local homelessness issues.

All SHSC agencies report standardised data about the clients they support each month to the AIHW, as specified by the SHS National Minimum Dataset (NMDS) . Data are collected about the characteristics and circumstances of clients when they first present at an agency. Further data on assistance received and client circumstances are collected at the end of every month in which the client receives services and again when contact with the client has ceased.

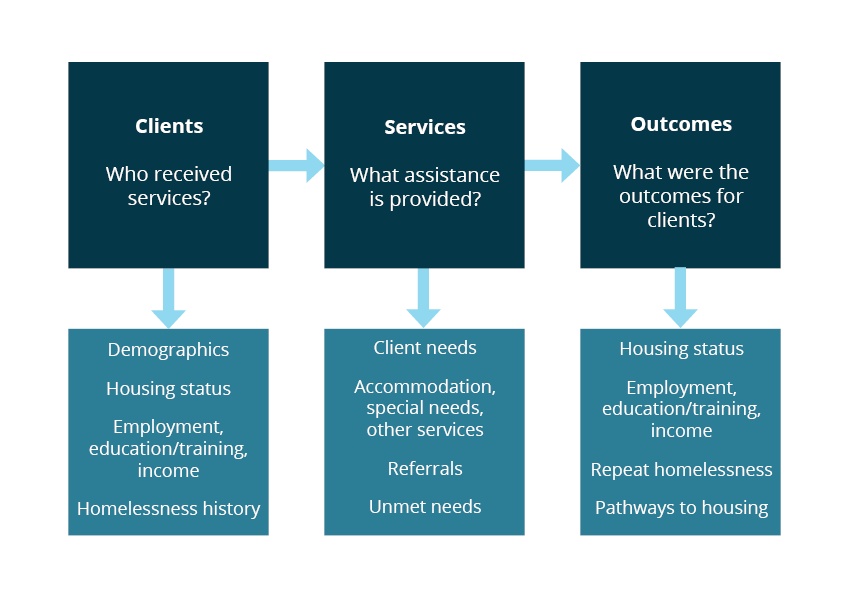

The SHSC is a comprehensive picture of clients, the specialist homelessness services that were provided to them and the outcomes achieved for those clients (Figure FRAMEWORK.1). The SHSC data provide a measure of the service response directed to those who are experiencing housing difficulty. The data do not provide a measure of the extent of homelessness in the community, although SHSC data on emergency accommodation and supported accommodation do contribute to the profile on homelessness in Australia.

Figure FRAMEWORK.1: Conceptual framework of the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection

The data in this publication draws on the SHSC to describe the support provided to people who are experiencing homelessness or are at risk of homelessness. Data from almost 1,700 SHS agencies across Australia are provided directly to the AIHW every month.

The data collected by agencies are based on periods of support provided to clients. Support periods vary in terms of their duration, the number of contacts between SHS workers and clients during the period and the reasons that support ends. Some support periods are relatively short – and are likely to have begun and ended in 2021–22 – while others are much longer, many of which might have been ongoing from the previous year and/or were still ongoing at the end of 2021–22.

On 1 July 2019, new data items were added to the SHSC and some other items were updated or modified. New data items include a National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) indicator, main language other than English spoken at home and proficiency in spoken English. The updated or modified data items include the addition of sex Other for clients and changes to items related to assistance for family and domestic violence. The ability to use and report on the new and updated data items in the Specialist Homelessness Services Annual Report for 2021–22 is dependent on data quality and the number of valid responses received.

Further information about the collection and information about the quality of the data obtained through the SHSC for 2021–22 is available in Technical notes.

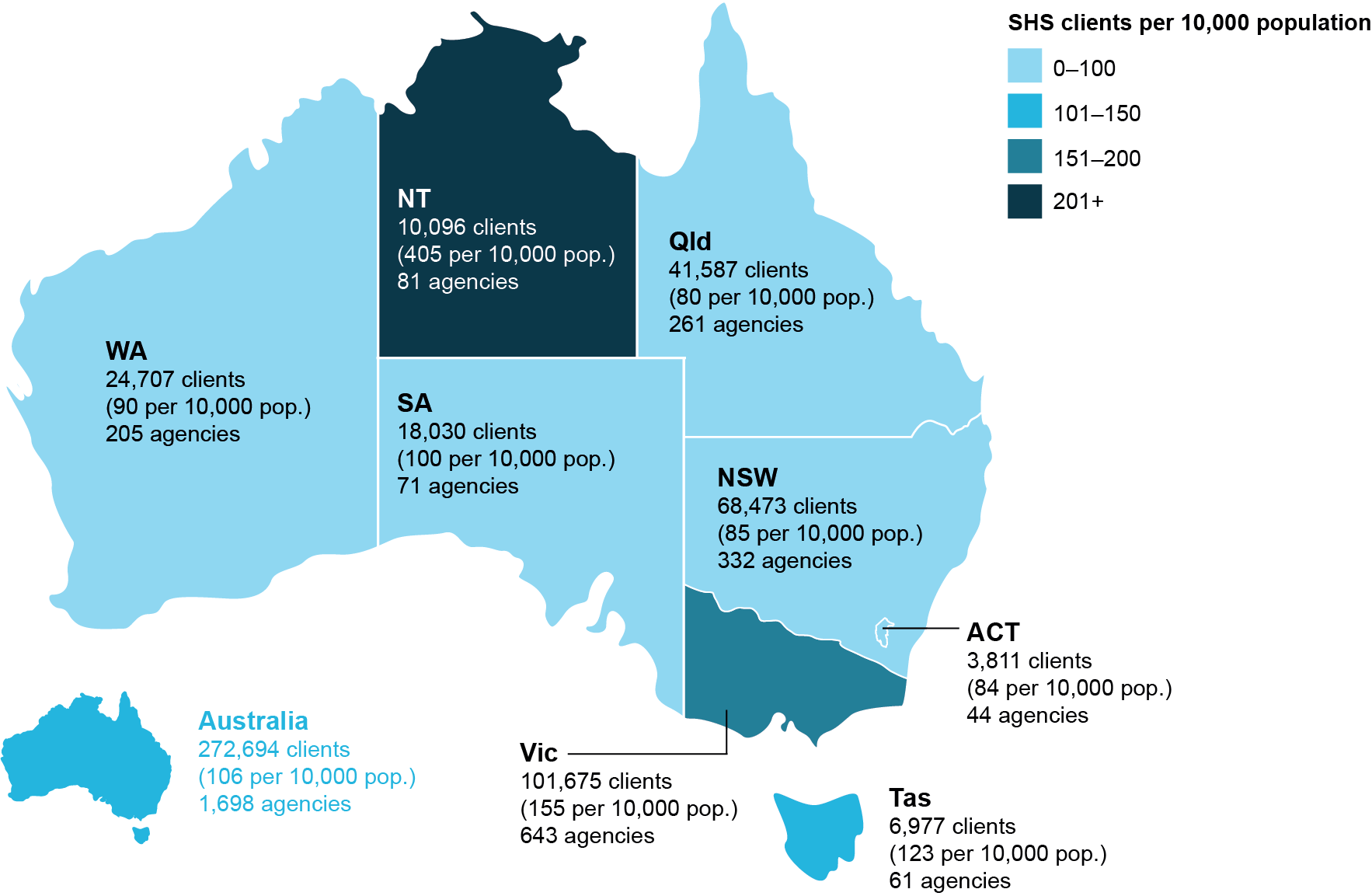

Nationally, 1,698 agencies delivered specialist homelessness services to almost 272,700 clients during 2021–22 (Figure FRAMEWORK.2).

Figure FRAMEWORK.2: Specialist homelessness agencies and clients by jurisdiction, 2021–22

Notes

- Clients may access services in more than one state or territory, therefore the Australia total will be less than the sum of jurisdictions.

- The agency count includes only those agencies that provided support periods with a valid Statistical Linkage Key (SLK).

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2021–22.

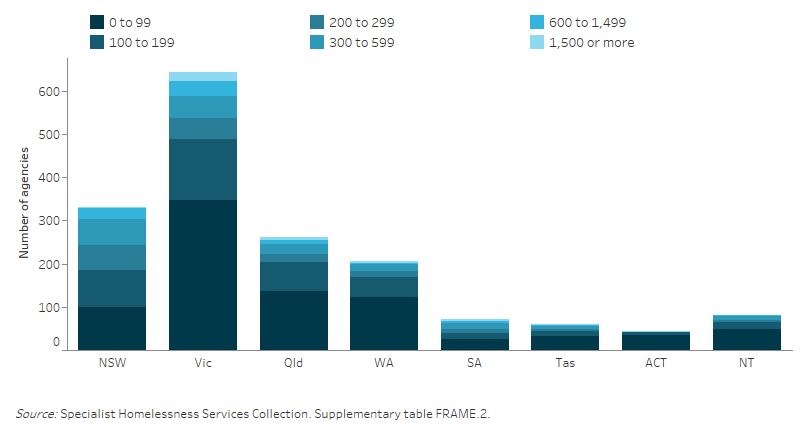

SHS agencies vary considerably in size, with some agencies assisting less than 100 clients per year and others assisting more than 1,500 people. Some agencies are represented by a larger ‘parent’ organisation while others are individual stand-alone agencies. The number of clients agencies assist (agency size) not only reflects the type and complexity of services provided, but also differing state and territory service delivery models. Agency size is also influenced by jurisdictional specific factors such as the size and geographical distribution of their population. Figure FRAMEWORK.3 illustrates the wide range in agency sizes in each state and territory. In 2021–22, about half of all agencies assisted fewer than 100 clients (845 agencies or 50%). Agencies assisting a large number of clients (more than 1,500 in 2021–22) exist in all jurisdictions, except the Northern Territory. Victoria had the most agencies of this size (21 agencies).

Figure FRAMEWORK.3: Specialist homelessness agencies, by number of clients assisted and state and territory, 2021–22

Specialist Homelessness Services and service delivery

Each state and territory manage their own system for the assessment, intake, referral and ongoing case management of SHS clients. The key delivery systems operating in Australia are summarised in Box FRAMEWORK.1. Although presented as 3 distinct models, these systems are representative of a range of approaches that jurisdictions may take to coordinate entry to becoming a client of SHS. Changes implemented by states and territories in the delivery of services and their associated responses have the potential to impact SHSC annual data.

Box FRAMEWORK.1

Community sector funding and support

- Assessment and intake: managed by individual SHS providers, consistent with state or territory policies

- Referral: refer to other SHS providers if clients’ needs can’t be met by initial SHS provider

- Can be supported by a coordinating service.

Central information management

- Assessment, intake and referral: managed at any SHS provider, via state or territory central information management tool

- Central information management system assists in the identification of appropriate services and indicates the availability/vacancy of services at all SHS providers.

Central intake

- Assessment, intake and referral: managed by one or more ‘central intake’ agency

- Central intake agencies prioritise access to services and only refer clients as services and/or vacancies are available

- Central information management tool may exist to share information between SHS providers.

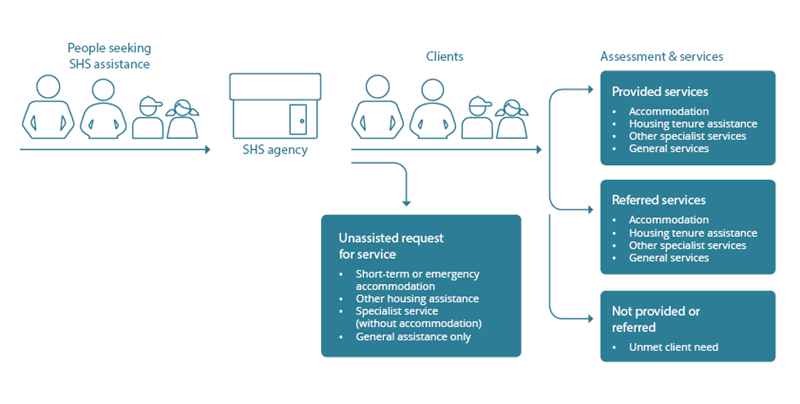

Once a person has made contact, specialist homelessness services can be provided to the client by the agency, or a client may be referred to another agency for a specific service (Figure FRAMEWORK.4). In some instances, a client may not receive nor be referred for a service and their need remains unmet. These unmet needs are captured to assist in determining the ability of the sector to respond to client needs.

An ‘unassisted request for service’ is an instance where a person(s) who approaches an agency is unable to be provided with any assistance (see Technical notes). Limited data are collected about these occasions.

Figure FRAMEWORK.4: Access to and delivery of Specialist Homelessness Services

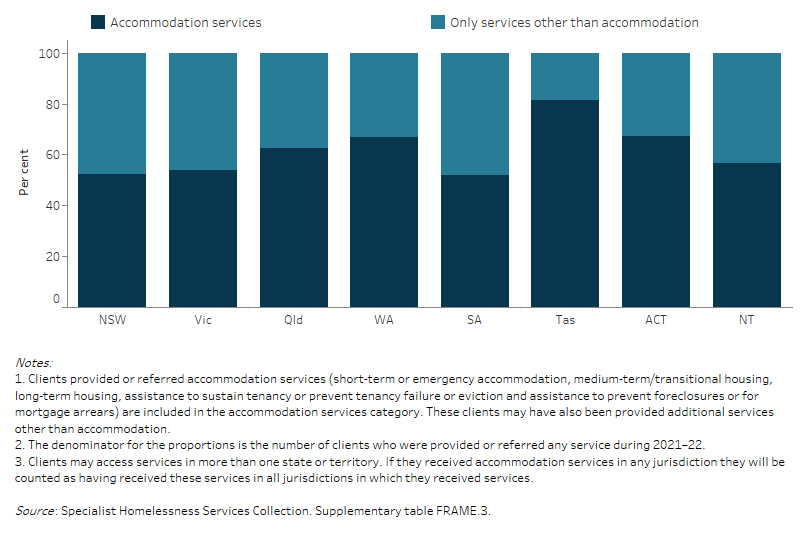

Services provided by specialist homelessness agencies in all states and territories can be categorised as either ‘accommodation services’ (either the direct provision or referral of accommodation or assistance for the client to remain housed) or ‘services other than accommodation’ (Figure FRAMEWORK.5). The proportion of SHS clients receiving accommodation services varied across states and territories in 2021–22, with more than 8 in 10 clients in Tasmania (81%), two-thirds of clients in the Australian Capital Territory (67%) and Western Australia (67%) and 6 in 10 clients in Queensland (62%) receiving these services. In contrast, the highest proportions of clients receiving services other than accommodation were in South Australia (48%), New South Wales (48%) and Victoria (46%). This variation likely reflects differences in the demand for accommodation services, differing service delivery models (that is, services other than those provided through SHS funding pathways) and housing options across jurisdictions.

Figure FRAMEWORK.5: Clients of Specialist Homelessness Services by service type, state and territory, 2021–22

COVID-19 effects on housing and homelessness and impacts on SHS support in 2021–22

The COVID-19 pandemic in Australia is part of the ongoing worldwide pandemic of the coronavirus disease 2019 with the first confirmed Australian case identified in January 2020 (Hunt 2020). During 2021–22, the pandemic response shifted to a new phase as people were able to access vaccinations, allowing for fewer lockdowns in most states and territories compared with the 2020–21 period.

The COVID-19 pandemic had substantial effects on the Australian housing system and people’s experiences of homelessness. During this time, Australian governments enacted a range of policy initiatives to protect vulnerable people from homelessness as well as to attempt to reduce the risk to vulnerable people of the health effects of the COVID-19 disease.

In the period captured in this report, that is, up to 30 June 2022, the various policies that were initially implemented by states/territories as a response to the pandemic have been amended to reflect the current environment. This may have impacted the number of SHS clients and the services they received.

See the COVID responses section in the Specialist Homelessness Services: monthly data report for details on the impact of these policies on SHS support.

Population Census results (conducted in August 2021) from the ABS will provide valuable updated insights on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on homelessness in Australia in this period (due to be released in 2023).

Housing market effects

Although a housing downturn was widely anticipated as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, housing prices increased sharply in the second half of 2020, largely assisted by a combination of record low interest rates in 2020 and 2021 and government action to directly stimulate market activity through homebuyer grants and associated assistance (for example the Australian Government’s $2.1 billion HomeBuilder initiative) (Pawson 2021).

Between March 2020 and February 2022, home values rose by around 25% (CoreLogic 2022). In May 2022, the RBA announced the first increase to the cash rate target since the beginning of the pandemic (RBA 2022) however, as this change was late in the reporting period, it is unlikely its impact will be reflected in this report.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the broader housing market situation also gave rise to unprecedented turbulence in Australia’s rental housing market (Pawson 2021). This was mainly as a consequence of rapidly rising house prices driving owners and investors to sell their properties, thereby reducing the available supply of rental housing. While a strong demand remained for rental properties, the smaller pool of available properties for rent drove up the price of rents.

These factors further exacerbated Australia’s existing housing affordability crisis, and longstanding low-income renters will likely face growing affordability stress as this pattern of higher housing demand and rising rents filters through the market affecting existing, as well as new, tenants (Pawson 2021). While rents declined slightly at the beginning of the pandemic, they had risen by nearly 12% by February 2022, increasing the median advertised rent by $30 per week (CoreLogic 2022). The impact of these affordability challenges on the rate of people experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness is yet to be fully realised.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022) Housing and occupancy costs, ABS website, accessed 27 September 2022.

Australian Government (2022) Budget October 2022–23: Cost of living relief, The Treasury website, accessed 31 October 2022.

Council on Federal Financial Relations (2018) National Housing and Homelessness Agreement, CFFR website, accessed 23 January 2019.

Chung RY, Chung GK, Gordon D, Mak JK, Zhang LF, Chan D, Lai FTT, Wong H, Wong SY (2020) ‘Housing affordability effects on physical and mental health: household survey in a population with the world’s greatest housing affordability stress’, J Epidemiol Community Health, 2020(74):164–172, doi:10.1136/jech-2019-212286.

CoreLogic (2022) Two years on: Six ways COVID-19 has shaped the housing market, CoreLogic website, accessed 20 September 2022.

Desmond M and Gershenson C (2016) ‘Housing and Employment Insecurity among the Working Poor’, Social Problems, 2016(0):1–22, doi:10.1093/socpro/spv025.

Gurran N, Hulse K, Dodson J, Pill M, Dowling R, Reynolds M and Maalsen S (2021) ‘Urban productivity and affordable rental housing supply in Australian cities and regions’, AHURI Final Report No. 353, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, doi:10.18408/ahuri5323001.

Hunt G (25 January 2020) First confirmed case of novel coronavirus in Australia [media release], Australian Government Department of Health, accessed 7 October 2022.

Pawson H (2021) ‘COVID-19 effects on housing and homelessness: the story to mid-2021’ in Australia’s welfare 2021: Data insights, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra.

RBA (3 May 2022) Minutes of the Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board, Reserve Bank of Australia website, accessed 20 September 2022.

Rowley S and Ong R (2012) ‘Housing affordability, housing stress and household wellbeing in Australia’, AHURI Final Report No.192, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

The Commonwealth of Australia (2021) ‘Budget paper no. 2: Budget measures’, Budget 2021–22, The Treasury website, accessed 7 October 2022.

The Commonwealth of Australia (2022) ‘Budget paper no. 3: Federal Financial Relations’, Budget 2022–23, The Treasury website, accessed 7 October 2022.