Birthweight

Data updates

25/02/22 – In the Data section, updated data related to birthweight are presented in Data tables: Australia’s children 2022 - Health. The web report text was last updated in December 2019.

Key findings

- In 2017, around 20,300 (6.7%) live-born babies were of low birthweight (less than 2,500 grams).

- Around 15% of low birthweight babies weighed less than 1,500 grams.

- Low birthweight was higher among mothers who smoked during pregnancy (12.9%) than mothers who did not (6%).

Low birthweight is a key indicator of a baby’s immediate health and a determinant of their future health. Low birthweight babies – whose weight at birth is less than 2,500 grams – are more likely to die in infancy or to be at increased risk of illness in infancy.

Long-term health effects can include poor cognitive development and increased risk of developing chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease later in life (WHO 2014). Children born with very low birthweight are especially at high risk of developmental difficulties, poor cognitive and motor skills (Scharf et al. 2016). The risk of dying is greater for babies of very low birthweight (Mayor 2016).

Evidence has found that factors influencing low birthweight include:

- extremes of maternal age (younger than 16 or older than 40)

- multiple pregnancy

- obstetric complications

- chronic maternal conditions (for example, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy)

- infections (such as, malaria)

- nutritional status

- exposure to indoor air pollution

- tobacco

- drug use (Blencowe et al. 2019).

Research from the Maternal Health Study conducted in Victoria found that women who experienced family violence were twice as likely to give birth to babies of low birthweight as women who did not experience violence (Brown et al. 2015).

Low birthweight is closely associated with pre-term birth – almost 3 in 4 low birthweight babies were pre-term, and more than half of pre-term babies were of low birthweight in 2017 (AIHW 2019a).

Babies may also be low birthweight because they are small for gestational age, while some low-birthweight babies may be both pre-term and small for gestational age. Babies who are small for gestational age indicates a possible growth restriction within the uterus (see, Where do I find more information?).

While this section focuses on low birthweight, high birthweight is also of concern. Evidence based on data from 12 high, middle and low-income countries indicates that higher birthweight was associated with increased odds of obesity among children aged 9–11 (Qiao et al. 2015).

Box 1: Data source on low birthweight babies

Data on birthweight is sourced from the National Perinatal Data Collection (NPDC). The NPDC is a national population-based cross-sectional collection of data on pregnancy and childbirth. The data are based on births reported to the perinatal data collection in each state and territory in Australia.

How many babies are of low birthweight?

In 2017, around 20,300 (6.7% of around 303,000) liveborn babies were of low birthweight. Girls were slightly more likely to be of low birthweight than boys (7.3% compared with 6.1%, respectively). Around 15% of low birthweight babies weighed less than 1,500 grams (AIHW 2019a).

In 2017, the proportion of low birthweight babies was higher among twins (55%) and other multiple birth babies (99%) compared with singletons (5.2%). It was also higher among mothers who smoked during pregnancy (13%) than mothers who did not (6.0%) (AIHW 2019a).

In 2017, the proportion of pre-term babies of low birthweight was considerably higher than that of full-term babies (57% and 2.2%, respectively).

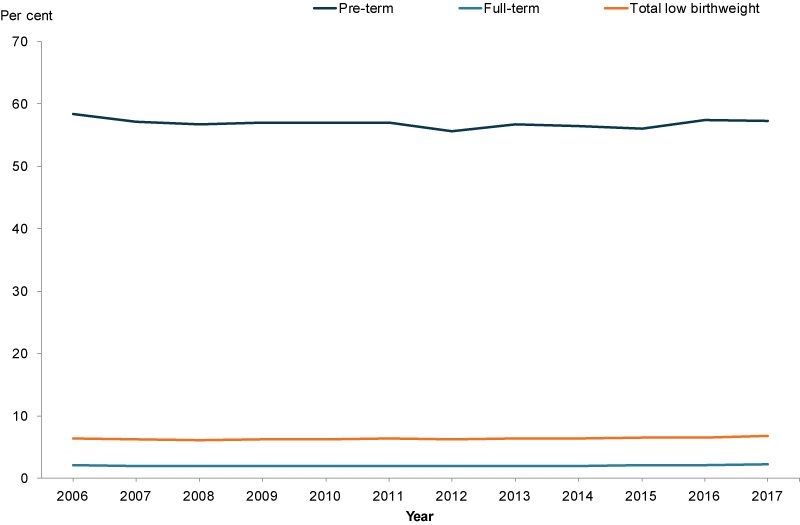

Have low birthweight rates changed over time?

The proportion of liveborn low birthweight babies was fairly stable in the 11 years to 2017 ranging between 6.1% and 6.7% (Figure 1). The proportion of pre-term babies of low birthweight ranged between 56% and 58% during this time, while for full-term babies the rate ranged between 1.9% and 2.2%.

Figure 1: Low birthweight liveborn babies, 2006 to 2017

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW NPDC.

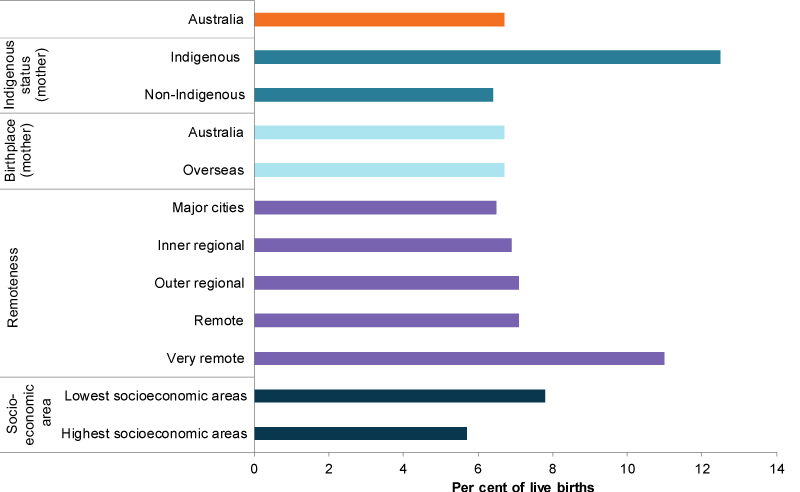

Are low birthweight rates the same for everyone?

Low birthweight rates vary across some population groups. In 2017, babies born in:

- Very remote areas (11%) were more likely to be of low birthweight than those born in Major cities (6.5%).

- areas of greatest socioeconomic disadvantage were also more likely to be of low birthweight (7.8%) than those born in areas of least disadvantage (5.7%) (Figure 2).

Differences were also evident between babies of Indigenous mothers and those of non-Indigenous mothers (13% and 6.4% born of low birthweight, respectively). The proportion of low-birthweight babies born to Indigenous mothers remained relatively stable between 2006 (12.4%) and 2017 (12.5%). See also Indigenous children.

Not all these categories are mutually exclusive. It is likely that some of these influencing factors overlap.

Figure 2: Low birthweight babies by selected population groups, 2016

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW NPDC.

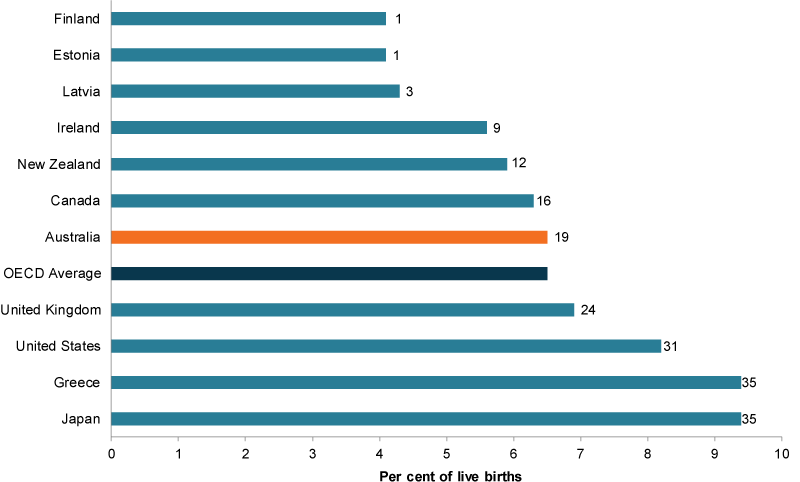

How does Australia compare internationally?

Internationally, Australia’s proportion of low birthweight babies was equal to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average (6.5%). The proportion of low birthweight babies was lowest in Finland and Estonia (4.1% each), and highest in Greece and Japan (9.4% each) (OECD 2018).

Figure 3: Low birthweight babies by selected OECD countries and rankings, 2016 or latest available

Notes: Data for Canada refer to 2014, and for Australia, to 2015. Exact definitions of low birthweight and of live births may differ slightly across countries. Data in this graph are for OECD member states only. Graph reflects top 3 countries, English-speaking background countries, and bottom ranked countries.

Chart: AIHW. Source: OECD Family Database.

Data limitations and development opportunities

While low birthweight is both a national and international indicator of infant health, it does have limitations as birthweight alone does not account for differentiation in growth status and maturity. Pre-term babies are inherently of low birthweight but may be of normal birthweight for their gestational age (AIHW 2019b).

Where do I find more information?

For more information on:

- low birthweight for Indigenous children, see Indigenous children

- birthweight data, see: Australia’s mothers and babies 2017—in brief. Data tables and Healthy community indicators.

- low birthweight, see: Low birthweight in Children’s Headline Indicators.

- birthweight including adjusted for gestational age, see: Baby outcomes in Australia’s mothers and babies data visualisations.

- birthweight of stillborn babies, see: Australia’s mothers and babies 2017—in brief.

- small babies among births at or after 40 weeks gestation, see: National Core Maternity Indicators.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019a. Australia’s mothers and babies 2017—in brief. Perinatal statistics series no. 35. Cat. no. PER 100. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019b. Australia’s mothers and babies data visualisations—birthweight. Cat. no. PER 101. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 25 September 2019.

Blencowe H, Krasevec J, Mercedes de Onis M, Black R, Xiaoyi An M, Gretchen A Stevens D et al. 2019. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birthweight in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health 7(7):e849–60.

Brown S, Gartland D, Woolhouse H & Giallo R 2015. Maternal health study policy brief no. 2: health consequences of family violence. Melbourne: Murdoch Children’s Research Institute. Viewed 21 March 2019.

Mayor S 2016. Low birth weight is associated with increased deaths in infancy and adolescence, study shows. The BMJ 353:i2682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2682.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) 2018. OECD Family Database. Paris: OECD. Viewed 21 March 2019.

Qiao Y, Ma J, Wang Y, Katzmarzyk P, Chaput J, Fogelholm M et al. 2015. Birth weight and childhood obesity: a 12-country study. International Journal of Obesity Supplements 5, S74–S79.

Scharf RJ, Stroustrup A, Conaway MR & DeBoer MD 2016. Growth and development in children born very low birthweight. Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition 101(5):F433–F438.

WHO (World Health Organization) 2014. Global nutrition targets 2025: low birth weight policy brief. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 21 March 2019.

AIHW National Perinatal Data Collection

- Includes liveborn babies of at least 400 grams birthweight or at least 20 weeks gestation (excludes stillborn babies).

- Data includes non-residents, residents of external territories and records where geographic area of usual residence was not stated (with the exception of remoteness and socioeconomic status categories).

- Data on Indigenous births relate to babies born to Indigenous mothers only, and exclude babies born to non-Indigenous mothers and Indigenous fathers. Therefore, the information is not based on the total count of Indigenous babies. Excludes births to mothers for whom Indigenous status was not stated.

- For 2017, Remoteness area derived by applying ABS 2016 Australian Statistical Geography Standard to area of mother’s usual residence.

- For 2017, Socioeconomic status derived by applying ABS 2016 Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage to area of mother's usual residence.

- For more information on data quality, see the National Perinatal Data Collection Data Quality Statement.

For more information, see Methods.