Smoking

Tobacco smoking is one of the largest single preventable causes of death and disease in Australia. It is a major risk factor for many chronic conditions, including coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, multiple types of cancers, and asthma (AIHW 2019). In 2019, 13% of males and 10% of females in Australia, aged 18 and over, smoked daily (AIHW 2020).

Smoking is common in groups over-represented in the prison population (AIHW 2013) – that is, smoking rates are much higher among people living in low socioeconomic areas, First Nations people, people with mental health disorders, people with substance use disorders, people who are unemployed and people experiencing homelessness (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023; Twyman et al. 2014).

While smoking has decreased over time in the general community in Australia, the same is not true for people in custody, whose smoking rates, in facilities that allow smoking, remain high.

Smoking bans have been implemented in most prisons across Australia. Of the 73 participating prisons in the 2022 NPHDC:

- 58 enforced smoking bans

- 15 allowed smoking.

Banning smoking in prison can reduce mortality rates among people in prison from smoking‑related causes, particularly cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, and cancer (Binswanger et al. 2014).

The National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030 recognises the high smoking rates in the prison population, and that prisons are an important setting for tobacco control efforts. It recommended that people in prison be provided more support to quit, including access to nicotine replacement therapy and other pharmacotherapies (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023). However, the majority of ex-smokers released from smoke-free prisons resume smoking, so smoking cessation support and policy attention are also required for people after their release from prison, and to ensure continuity of care (Puljević et al. 2018).

Smoking among prison entrants

Prison entrants were asked whether they had ever smoked tobacco, whether they currently smoked, and how old they were when they had their first full cigarette.

Of 371 prison entrants, 86% said they had smoked a full cigarette at some stage in their lives and 13% said they had never smoked a full cigarette.

The average age that prison entrants reported smoking their first full cigarette was 14.2 (Indicator 2.2.2).

Almost 3 in 4 (71%) prison entrants reported that they currently smoked tobacco. About 4 in 5 (79%) First Nations prison entrants and almost 2 in 3 (64%) non-Indigenous entrants reported they were current smokers.

Female prison entrants (75%) were more likely than male prison entrants (70%) to report they were current smokers. Entrants aged 35–44 were the most likely group to report being current smokers (76%), and those aged 45 and over were least likely (61%).

Almost 2 in 3 (64%) prison entrants reported they smoked tobacco daily (Indicator 2.2.3).

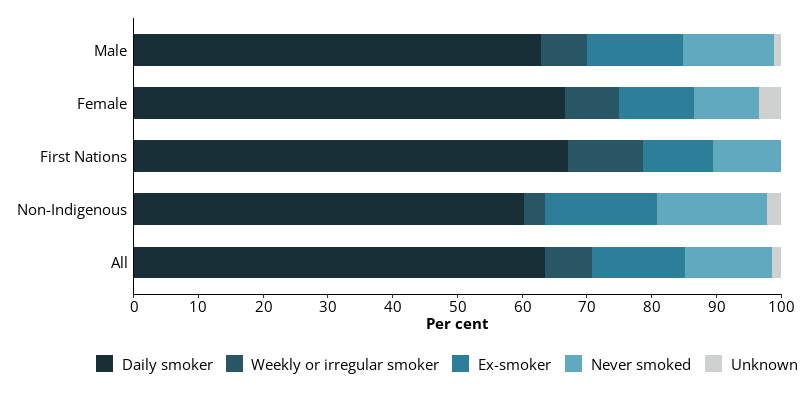

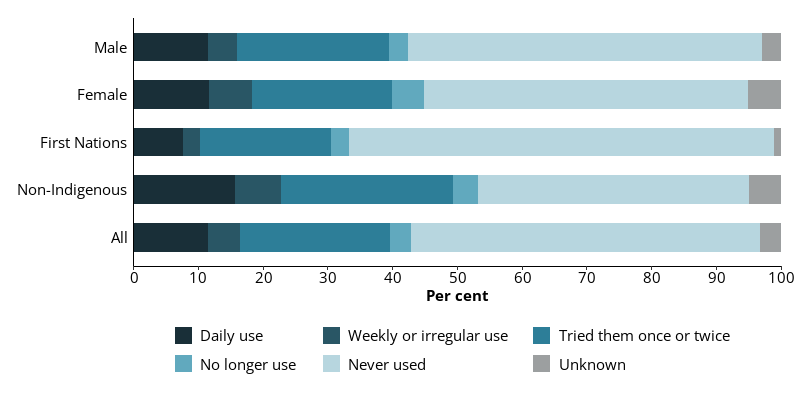

Rates of daily smoking were similar among females and males, with 67% female entrants and 64% male entrants reporting they smoked daily (Figure 9.4).

First Nations entrants (67%) were more likely than non-Indigenous entrants (60%) to report they smoked daily (Figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4: Prison entrants, frequency of tobacco smoking, by sex and Indigenous identity, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Entrants form, 2022 NPHDC.

Prison entrants were asked about their household’s exposure to smoke in the last 12 months. Over a half of prison entrants (55%) reported that someone in their home smoked daily inside the home. About one-quarter (28%) of entrants reported that people in the household would only smoke daily outside and 14% reported that no one in the home regularly smoked.

Smoking among prison dischargees

Prison dischargees were asked whether they had smoked tobacco on their current prison entry, whether they smoked in prison, and their intentions to smoke on release.

Almost 3 in 4 (72%) dischargees reported they smoked tobacco on entry to prison.

Of 200 First Nations dischargees, 78% reported they smoked on entry to prison while 23% reported they did not.

Of 231 non-Indigenous dischargees, 68% reported they smoked on entry to prison while 32% reported they did not.

Prison dischargees aged 35–44 (80%) were the group most likely to report they were current smokers on prison entry, and those aged 18–24 (63%) were the least likely.

Of prison dischargees in all participating prisons, about one-third (35%) reported being current smokers, down from the 72% of all dischargees who said they smoked on entry to prison.

In prisons that allowed smoking, 4 in 5 (82%) prison dischargees reported they currently smoked tobacco (Indicator 2.2.4).

Smoking bans in prison have an impact on the proportions of people in custody who reported they currently smoked. Smoking bans have been implemented in most prisons across Australia. Of the 73 prisons which participated in the NPHDC, 58 had complete smoking bans. About 1 in 4 (29%) dischargees from prisons that banned smoking said they were current smokers.

In prisons that allowed smoking:

- almost 3 in 4 (71%) dischargees aged 45 and over said they were current smokers, while 100% of dischargees aged 25–34 said they were current smokers

- almost 9 in 10 (88%) First Nations dischargees, and 3 in 4 (75%) non-Indigenous dischargees said they were current smokers

- one-quarter (23%) of dischargees reported they smoked less at discharge.

Smoking comparisons with the general community

Smoking rates among people entering prison were much higher than in the general community. Comparisons were made between prison entrants in the 2022 NPHDC with people aged 18 and over in the 2019 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (AIHW).

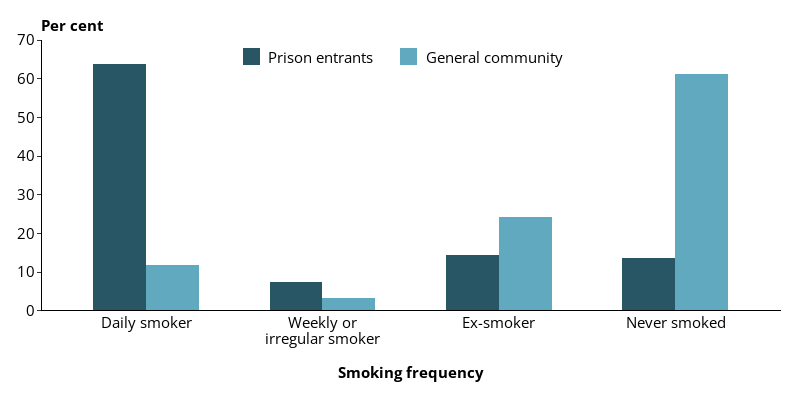

Striking differences were found between the proportions of prison entrants and the general population who were daily smokers or who had never smoked.

Over a half (64%) of prison entrants were daily smokers, compared with about 1 in 8 (12%) people in the general community (AIHW 2020) (Figure 9.5).

About 1 in 8 (13%) prison entrants said they had never smoked, compared with 61% in the community (AIHW 2020) (Figure 9.5).

Two-thirds (67%) of First Nations prison entrants reported they were a daily smoker compared with 28% of First Nations people in the general community. Of all non-Indigenous prison entrants, 60% reported they were a daily smoker compared with 11% of non‑Indigenous people in the general community.

The proportion of people in the community who reported never having smoked was highest among younger people (80% of those aged 18–24 in 2019), suggesting that fewer young people in the general population were trying and taking up smoking (AIHW 2020). In contrast, only 15% of prison entrants aged 18–24 had never smoked.

Figure 9.5: Prison entrants (2022) and the general community (2019), frequency of tobacco smoking

Notes

- Proportions of prison entrants are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Prison entrants excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Sources: AIHW 2020; Entrants form, 2022 NPHDC.

Quitting smoking

Quitting smoking is difficult, and people released from smoke-free prisons often relapse (Jin et al. 2018). Commonly perceived barriers to quitting successfully include:

- poor stress management

- lack of professional support

- the high prevalence and acceptability of smoking in vulnerable communities (Twyman et al. 2014).

Most prisons offer programs for those who wish to stop smoking, or to cope with quitting in a smoke-free facility. But, relapse upon release is common, and smoking cessation support is required for people transitioning to the community (Brose et al. 2018; Puljević et al. 2018).

Quitting smoking among prison entrants

Prison entrants who reported they were current smokers were asked whether they wanted to quit smoking, and which resources they would find helpful.

About a half (48%) of prison entrants who were current smokers wanted to quit (Indicator 2.2.5).

Older prison entrants were more likely than younger entrants to report they wanted to quit smoking. Almost 3 in 5 (57%) entrants aged over 45 reported they wanted to quit smoking compared with 2 in 5 (39%) of those aged 18–24.

Female prison entrants were more likely (53%) than male prison entrants (46%) to report that they wanted to quit smoking.

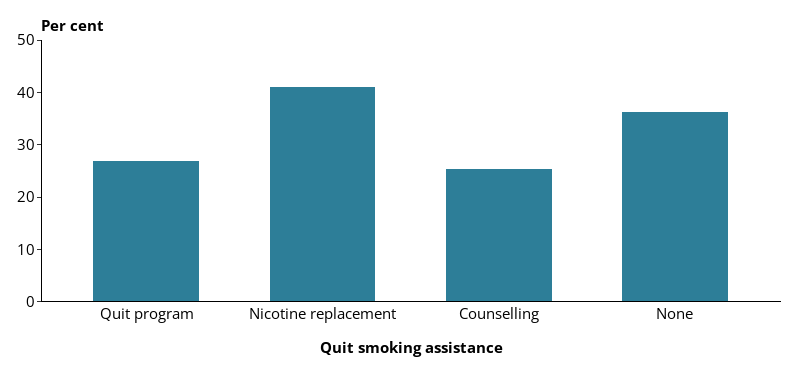

Of prison entrants who wanted to quit smoking:

- about 2 in 5 (41%) said nicotine replacement therapy would help

- about one-quarter (27%) said a quit program would help

- one-quarter (25%) said counselling would help

- about one-third (36%) said they did not want any help (Figure 9.6).

Figure 9.6: Prison entrants, current smokers, by support required to quit smoking, 2022

Notes

- Entrants could select multiple answers.

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Entrants form, 2022 NPHDC.

Quitting smoking among prison dischargees

Prison dischargees were asked about the resources they knew were available in prison to help them quit smoking, and whether they had used any of these.

Of those who knew assistance was available, nicotine replacement therapy was most commonly used – with about 1 in 10 (11%) prison dischargees who were current smokers on entry to prison choosing this option.

Smoking intentions on release

Prison dischargees were asked about their intention to smoke on release from prison.

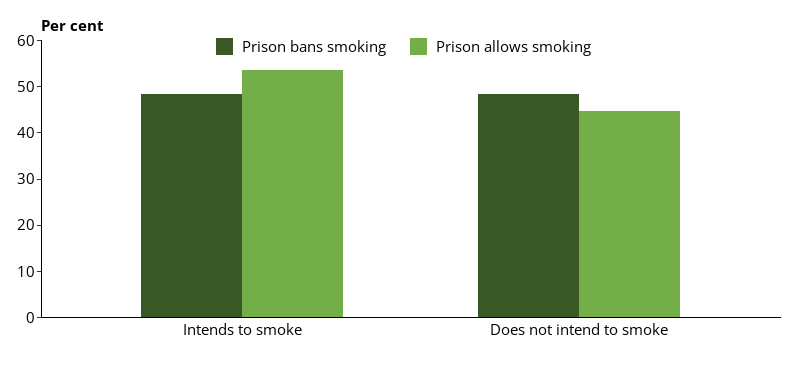

About a half (49%) of prison dischargees who were current smokers on prison entry intended to smoke on release (Indicator 2.2.6).

There was little difference in prison dischargees’ intention to smoke on release – 48% of dischargees from 60 prisons that banned smoking, and 54% from 15 prisons that allowed smoking intended to smoke on release (Figure 9.7).

Figure 9.7: Prison dischargees, intention to smoke on release, by smoking ban status of prison, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Dischargees form, 2022 NPHDC.

E-cigarette (vaping) use

E-cigarettes, or vapes, are electronic devices containing a chemical liquid that is heated to produce an aerosol vapour. This vapour is inhaled by the user, which may have harmful consequences for their health (NHMRC 2022).

Prison entrants were asked about their e-cigarette use. Of 371 prison entrants, 43% reported they had used an e-cigarette at least once. Of those who had used an e-cigarette, 7.5% reported they no longer used them. Prison entrants were considered to be ‘current users’ of e-cigarettes if they reported using them on a weekly or irregular, or daily basis.

About one-quarter (23%) of prison entrants reported trying e-cigarettes once or twice, while about 1 in 8 (12%) reported they used e-cigarettes daily (Figure 9.8).

Two-thirds of First Nations prison entrants had never used an e-cigarette (66%). About 1 in 5 (20%) of First Nations prison entrants reported they had used them once or twice and 7.7% reported they used e-cigarettes daily (Figure 9.8).

More than a half (53%) of non-Indigenous prison entrants had used e-cigarettes at least once. About 1 in 4 (27%) non-Indigenous prison entrants reported they had tried e-cigarettes once or twice and 16% reported they used e-cigarettes daily (Figure 9.8).

Figure 9.8: Prison entrants, frequency of e-cigarette use, by sex and Indigenous identity, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Entrants form, 2022 NPHDC.

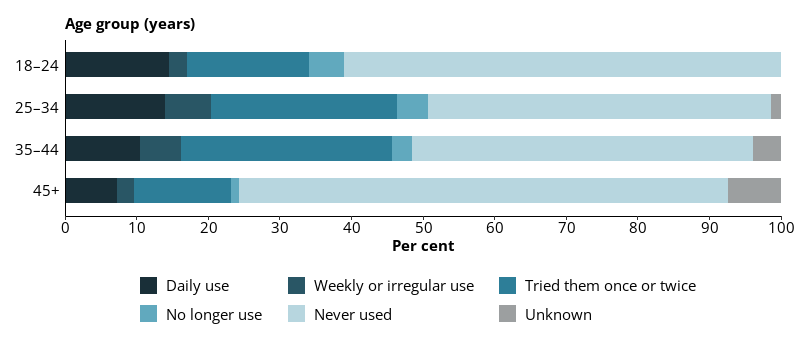

Young people were more likely to report daily use of e-cigarettes than those in older age groups. About 1 in 7 (15%) prison entrants aged 18–24 reported using e-cigarettes daily while about 1 in 14 (7.3%) prison entrants aged 45 and over reported using e-cigarettes daily (Figure 9.9).

Figure 9.9: Prison entrants, frequency of e-cigarette use, by age, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Entrants form, 2022 NPHDC.

Vaping comparisons with general community

About 2 in 5 (43%) prison entrants reported they had used an e-cigarette at least once compared with 1 in 11 (9.3%) adults in the general community (ABS 2022). Consistent with e-cigarette usage among prison entrants, the proportion of those in the community who had ever used an e-cigarette was higher in those aged 18–44 than in those aged over 45.

Male prison entrants were almost 4 times as likely to report ever using an e-cigarette (43%) than males in the community (11%).

Female prison entrants were 6 times more likely to report ever using an e-cigarette (45%) than females in the community (7.5%).

About 1 in 6 prison entrants reported currently using e-cigarettes (16%) while 3.2% reported that they no longer use them. By contrast, people in the community were more likely to report that they no longer used e-cigarettes (7.1%) than current e-cigarette use (2.2%).

In the community, and among prison entrants, those aged 18–24 were the group most likely to report currently using e-cigarettes; however, prison entrants aged 18–24 were more than 3 times as likely to report currently using e-cigarettes (17%) than people of the same age in the community (4.8%) (ABS 2022).

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2022) Smoking, ABS website, accessed 26 April 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2013) Smoking and quitting smoking among prisoners in Australia 2012, AIHW website, accessed 22 April 2023.

—— (2019) Burden of tobacco use in Australia: Australian Burden of Disease Study 2015, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 10 October 2023. doi:10.25816/5ebca654fa7de.

—— (2020) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, AIHW website, accessed 24 April 2023, doi:10.25816/e42p-a447.

Binswanger IA, Carson EA, Krueger PM, Mueller SR, Steiner JF and Sabol WJ (2014), ‘Prison tobacco control policies and deaths from smoking in United States prisons: population based retrospective analysis’, BMJ, 349:g4542.

Brose LS, Simonavicius E and McNeill A (2018) ‘Maintaining abstinence from smoking after a period of enforced abstinence – a systematic review, meta-analysis and analysis of behaviour change techniques with a focus on mental health’, Psychological Medicine, 48(4):669–78

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030, Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government, Canberra.

Jin, X., Kinner, S.A., Hopkins, R., Stockings, E., Courtney, R.J., Shakeshaft, A., Petrie, D., Dobbins, T. and Dolan, K., (2018) Brief intervention on Smoking, Nutrition, Alcohol and Physical (SNAP) inactivity for smoking relapse prevention after release from smoke-free prisons: a study protocol for a multicentre, investigator-blinded, randomised controlled trial. BMJ open, 8(10), p.e021326.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (2022) CEO statement: electronic cigarettes, NHMRC, Canberra.

Puljević C, de Andrade D, Coomber R and Kinner SA (2018) ‘Relapse to smoking following release from smoke-free correctional facilities in Queensland, Australia’, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 187(1):127–133.

Twyman L, Bonevski B, Paul C and Bryant J (2014) ‘Perceived barriers to smoking cessation in selected vulnerable groups: a systematic review of the qualitative and quantitative literature’, BMJ Open 4:e006414.