Continuing care

Continuity of care is necessary to maintain any health improvements achieved by people in prison. Many people lose any health gains they made in prison within a few months of release, which affects not only the individual, but the entire community (Kouyoumdjian et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2010).

Some barriers to continuity of care can be overcome by ensuring that everyone released from prison has immediate access to health care, with:

- a valid Medicare card or number, where eligible, from the day of their release

- immediate access to required medications or treatment

- immediate access to accommodation and support services.

Compliance with a treatment plan depends on the person’s knowledge of their health conditions, including the medications and other treatments they require. This knowledge has been found to be lacking for many people released from prison (Carroll et al. 2014).

Health-related discharge planning

People in prison often have multiple and complex health needs, making their return to the community a time of increased risk to their health and wellbeing (Thomas et al. 2016; Young et al. 2015).

Discharge planning supports the continuity of health care between prison and the community, and is necessary for a successful transition (Kinner et al. 2012). A discharge summary provides an individual plan for the continuity of care of a person from prison to the community. It incorporates referrals to appropriate community-based services and ensures medications, health services and other support services are accessible.

With an increasingly high proportion of prisoners on remand (70% of prison entrants and 44% of prison dischargees were on remand in the 2022 NPHDC), the timing of release from prison is often uncertain. It is relatively common for a person on remand to leave prison to attend court, and then be released directly from court into the community.

Sentenced prisoners might also experience an unplanned release, such as from a parole hearing or appeal proceeding in court. So, it can be difficult for clinic staff to know when to begin discharge planning for many of the people in prison.

Discharge summaries on file when released

Prison clinics in New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory provided information on how many remand and sentenced prisoners were released during the 2-week data collection period, and whether, for sentenced prisoners, these releases were planned or unplanned.

These prison clinics also provided information on how many people had a written discharge summary on file at the time of their release.

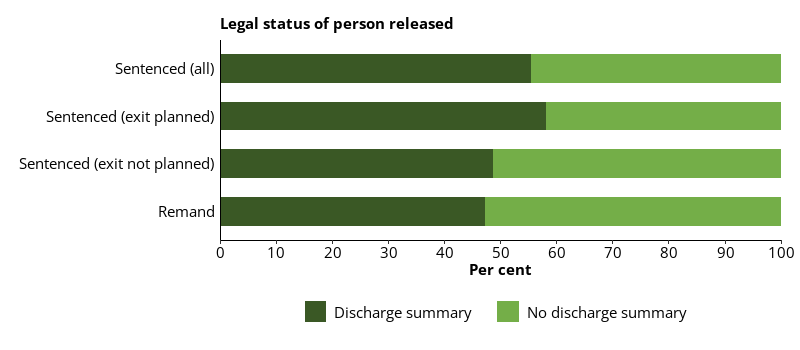

More than a half (56%) of sentenced prisoners had a discharge summary on file when they were released (Indicator 3.1.17).

Of the 731 sentenced prisoners who were released during the 2-week data collection period, 528 had a planned exit and 203 had an unplanned exit. Of those who had a planned exit, 58% had a health-related discharge summary on file at the time of their release. Of those who had an unplanned exit, 49% had a discharge summary on file (Figure 10.14).

Of the 477 people who were released while on remand, 47% had a discharge summary on file (Figure 10.14).

Figure 10.14: Proportion of people released from prison who had a health-related discharge summary in place, by legal status, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia, Northern Territory and one Queensland prison, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Establishment form, 2022 NPHDC.

Prison clinics were asked to provide information on their typical prisoner release procedures. Release procedures and the health-related discharge summary varied according to the facility, and according to the health needs of the person in custody.

People released from prison were more likely to have a detailed health-related discharge summary if they had a history of a mental health condition, other chronic health condition, or an alcohol and other drug use disorder, or if they were on regular medication.

Prison clinics reported that, in general, the process for health-related discharge planning included:

- a review at the prison clinic of the person due to be released

- advice and education for the patient regarding health conditions, medications, upcoming appointments, as well as on safe drug use and overdoses for patients with substance use disorders

- a discharge summary or discharge health report and letter for the patient’s GP being prepared, and either given to the person due for release or forwarded to their GP, community clinic, or health service

- a discharge summary being prepared, containing the patient’s medical history, current problems, allergies, dietary requirements or other needs, future appointments scheduled, relevant pathology and radiology tests, any current medication, vaccination record, and clinic contact details for further information

- a referral to appropriate community services such as GPs, community health clinics, Aboriginal medical services or health clinics, mental health services, psychologists, and/or accommodation support, as required

- a referral or appointment to a specialist, hospital, or program for services such as opioid substitution therapy, to ensure continuity of care

- for some clinics, a limited supply of ongoing medication (1–2 weeks), or arrangements for these to be collected from a pharmacy in the community.

Referral to health professionals after release for prison dischargees

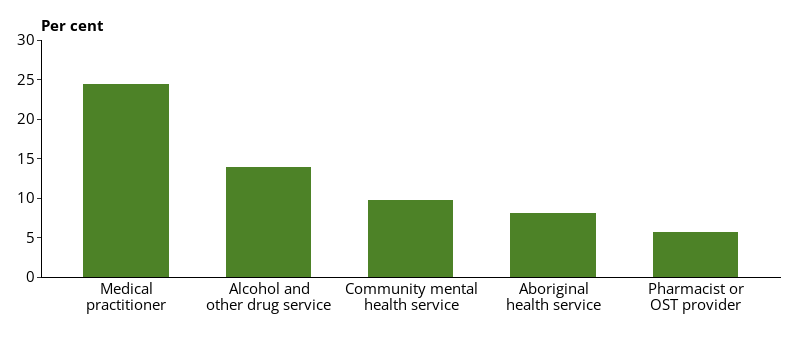

More than 2 in 5 (42%) prison dischargees reported they had a referral or an appointment to see a health professional after release (Indicator 3.1.18).

Females (55%) were more likely than males (40%) to report having a referral or appointment scheduled with a health professional after release from prison.

Non-Indigenous dischargees (43%) were similarly as likely as First Nations dischargees (41%) to report having a referral or appointment scheduled with a heath professional after release.

Dischargees aged 45 and over (46%) were the most likely to have a referral or appointment scheduled with a health professional after their release from prison, and those aged 18–24 were the least likely (22%).

Of all prison dischargees:

- about 1 in 4 (24%) had a referral or appointment scheduled to see a medical practitioner after release

- about 1 in 7 (14%) had a referral or appointment to an alcohol and drug treatment or counselling service

- about 1 in 10 (9.7%) had a referral or appointment to a community mental health service

- 8.1% had a referral or appointment to an Aboriginal medical service

- 5.6% had a referral or appointment to a pharmacist or opioid substitution therapy provider (Figure 10.15).

Figure 10.15: Prison dischargees, self-reported referral or appointment to see a health professional after release, by type of health professional or service, 2022

Notes

- Multiple options could be selected.

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Dischargees form, 2022 NPHDC.

Carroll M, Kinner SA and Heffernan EB (2014) ‘Medication use and knowledge in a sample of Indigenous and non-Indigenous prisoners’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 38:142–146.

Kinner SA, Streitberg L, Butler T and Levy M (2012) ‘Prisoner and ex-prisoner health: improving access to primary care’, Australian Family Physician, 41(7):535–537.

Kouyoumdjian FG, Cheng SY, Fung K, Orkin AM, McIsaac KE, Kendall C, Kiefer L, Matheson FI, Green SE and Hwang SW (2018) ‘The health care utilization of people in prison and after prison release: a population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada’, PLoS One, 13(8):e0201592, doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0201592.

Thomas EG, Spittal MJ, Heffernan EB, Taxman FS, Alati R and Kinner SA (2016) ‘Trajectories of psychological distress after prison release: implications for mental health service need in ex-prisoners’, Psychological Medicine, 46(3):611–621, doi:10.1017/S0033291715002123.

Wang EA, Hong CS, Samuels L, Shavit S, Sanders R and Kushel M (2010) ‘Transitions clinic: creating a community-based model of health care for recently released California prisoners’, Public Health Reports, 125(2):171–177, doi:10.1177/003335491012500205.

Young JT, Arnold-Reed D, Preen D, Bulsara M, Lennox N and Kinner SA (2015) ‘Early primary care physician contact and health service utilisation in a large sample of recently released ex-prisoners in Australia: prospective cohort study’, BMJ Open, 5:e008021, doi:10.1136/bmjopen–2015–008021.