Self-assessed mental health status

Self-assessed health status is used extensively in public health research in the absence of more detailed objective health data. It is used in various data collections on numerous topics, making it useful for comparisons between different population groups (Wu et al. 2013).

Prison entrants and prison dischargees were asked to rate their mental health as being excellent, very good, good, fair or poor.

About 3 in 5 (59%) prison entrants described their mental health as good, very good, or excellent (Indicator 1.4.2).

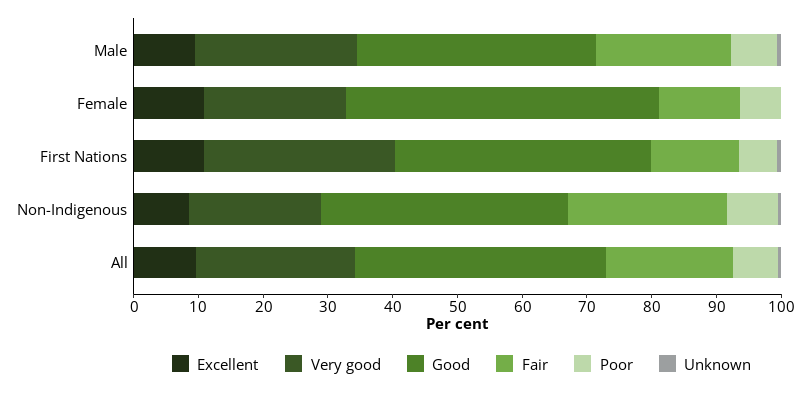

Almost 3 in 4 (73%) prison dischargees described their mental health as good, very good or excellent (Indicator 1.4.3).

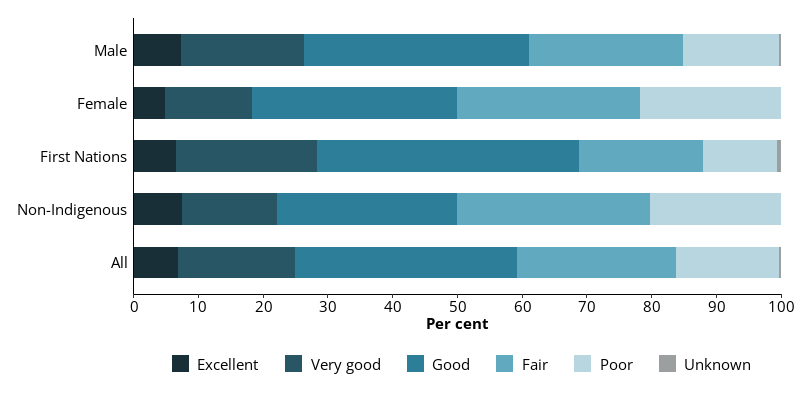

Male prison entrants were more likely (61%) than female entrants (50%) to report their mental health as good, very good or excellent (Figure 5.2). Overall, prison dischargees were more likely than prison entrants to report their mental health as being good or better, with more than 4 in 5 (81%) female dischargees, and almost 3 in 4 (72%) male dischargees, describing their mental health as good or better (Figure 5.3).

First Nations prison entrants (69%) were more likely than non-Indigenous prison entrants (50%) to describe their mental health as generally good or better (Figure 5.2). First Nations prison dischargees (80%) were also more likely than non-Indigenous prison dischargees (67%) to describe their mental health as generally good or better (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.2: Prison entrants, self-assessed mental health status, by sex and Indigenous identity, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Entrants form, 2022 NPHDC.

Figure 5.3: Prison dischargees, self-assessed mental health status, by sex and Indigenous identity, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Dischargees form, 2022 NPHDC.

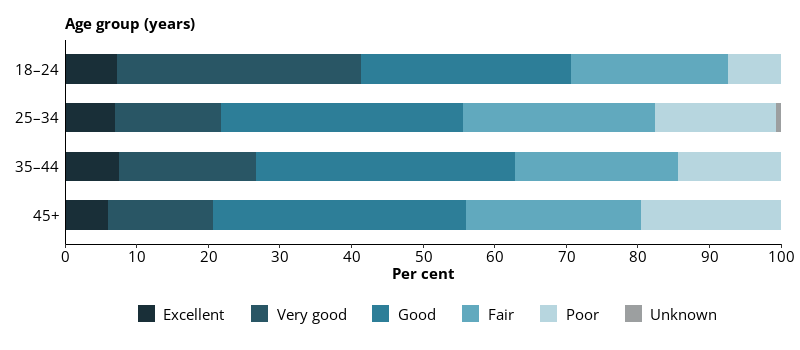

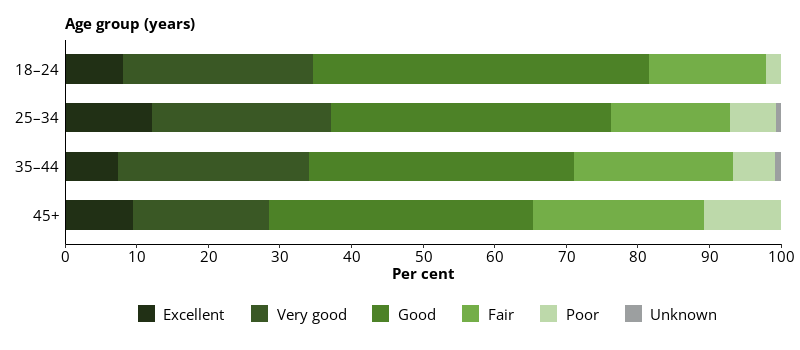

Prison entrants aged 18–24 (71%) were more likely to describe their mental health as generally good or better and those aged 25–34 and 45 and over were equally the least likely to do so (56%) (Figure 5.4). Similarly, prison dischargees aged 18–24 (82%) were more likely to describe their mental health as generally good or better and those aged 45 and over were the least likely (65%) (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.4: Prison entrants, self-assessed mental health status, by age, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Entrants form, 2022 NPHDC.

Figure 5.5: Prison dischargees, self-assessed mental health status, by age, 2022

Notes

- Proportions are representative of this data collection only, and not the entire prison population.

- Excludes Victoria, which did not provide data for this item.

Source: Dischargees form, 2022 NPHDC.

Prison dischargees change in mental health status while in prison

More than 4 in 5 (81%) prison dischargees reported their mental health improved or stayed the same while in prison (Indicator 1.4.4).

Prison dischargees were more likely to report that their mental health improved while in prison, with almost half (46%) reporting that it improved; one-third (34%) reported that it stayed the same and 1 in 5 (19%) that it worsened during their time in prison.

Males (47%) were more likely than females (39%) to report that their mental health improved while in prison. Females (44%) were more likely than males (33%) to report that it stayed the same, with females and males fairly similar in reporting that it had worsened in prison (16% and 20%, respectively).

Wu S, Wang R, Zhao Y, Ma X, Wu M, Yan X et al. (2013) ‘The relationship between self‑rated health and objective health status: a population-based study’, BMC Public Health, 13:320.